Older Patients With Schizophrenia: Nature of Dwelling Status and Symptom Severity

Abstract

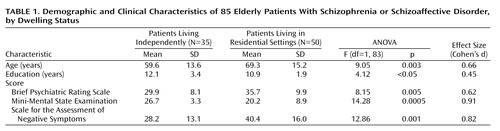

OBJECTIVE: This cross-sectional study enrolled elderly patients with diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. METHOD: The 85 subjects were dichotomized into two groups on the basis of dwelling status: those living independently (N=35) and those living in residential settings (N=50). The groups were compared with regard to scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), the Geriatric Depression Scale and by age. RESULTS: Patients living independently had significantly higher MMSE scores, lower SANS scores, more years of education, and were younger than the patients living in residential settings. CONCLUSIONS: These data suggest that although cognition, negative symptoms, and age are important discriminators with regard to dwelling status, cognition and negative symptoms appear to have the strongest impact.

There is limited information available about the attributes of older adults with serious and persistent psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and chronic depression (1). There are only a few studies that have focused on the prediction of dwelling status in older schizophrenic patients with regard to symptoms and cognitive status (2, 3).

We hypothesized that patients within the schizophrenia spectrum disorder who were living in a supervised setting would demonstrate more severe symptoms and greater cognitive impairment than those living independently. While these hypotheses would seem intuitively obvious, the study also attempted to compare the relative impact of these variables by examining the magnitude of their effect sizes.

Method

This study is part of a consortium for research on older people with schizophrenia, a multisite effort to study older patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The study group consisted of 85 patients (29 men and 56 women) with a medical chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were residing in group homes, family-care homes, nursing homes, and independent living settings. These patients were followed in a continuing day-treatment program, an outpatient clinic, or in a skilled nursing facility. The patients with mental retardation, severe head injury, or seizure disorder were excluded. The subjects were at least 55 years of age (mean=65.3, SD=15.2). A total of 38.8% were single, 23.5% were widowed, 24.7% were divorced, 8.2% were married, and 4.7% were separated. Their mean educational level was 11.39 years (SD=2.69); the majority were disabled (77.6%). The mean age at onset of illness was 30.3 years (SD=14.2). The prevalence of alcohol (4.9%) and drug (4.7%) abuse was low.

The institutional review board of Olean General Hospital approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects or the authorized representatives of those who lacked capacity. The patients were dichotomized into two groups on the basis of dwelling status: those who were living independently and those who were living in residential settings (group homes, family-care homes, or nursing homes). Group homes are run by a state-certified agency for patients with chronic mental illness. Family-care homes are privately owned and provide meals, lodging, and medication supervision for patients. The state pays the family (like a surrogate family) to look after individuals with chronic mental illness.

The two groups were compared with regard to scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (4), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (5), the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (6), the Geriatric Depression Scale (7) (administered by the same trained rater), level of education in years, and age. Statistical analysis was conducted by using SPSS (SPSS, Chicago). The data were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by using dwelling status as the independent variable. The magnitude of the effects was quantified by Cohen’s d (8, 9).

Results

Five variables differentiated the two groups, and these are displayed in Table 1. The two groups differed significantly on scores on the MMSE (the independent-living group scored higher), years of education (the independent-living group scored higher), age (the independent-living group scored lower), scores on the SANS (the independent-living group scored lower), and scores on the BPRS (the independent-living group scored lower). No significant differences were found with regard to depressive symptoms with scores on the Geriatric Depression Scale. The prevalence of diabetes in this group was 19%.

Discussion

The differences between the two groups in scores for negative symptoms and on the MMSE were prominently demonstrated by a robust effect size. Auslander et al. (3) used a younger cohort of patients, with a mean age of 55, who were predominantly male (64.4%) and mostly veterans, while ours was a community group, was older (with a mean age 65 years), and was composed of 65.9% women. The patients with prominent negative symptoms or a low cognitive level performed poorly with regard to their activities of daily living as well as the instrumental activities of daily living, resulting in the need for supervision.

In this study, the mean MMSE scores were 27 and 20 for those living independently and for those living in a supervised setting, respectively. This was consistent with our a priori hypothesis. The MMSE score is a relatively crude measure of cognition compared to the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (10), which was used by Auslander et al. (3); both studies revealing consistent findings with regard to cognition. MMSE scores may be used to help in the discharge planning of hospitalized patients with regard to living arrangements. There was a 6-point difference between the two groups in our study, with a mean BPRS score of 30 for those living independently and 36 in those in supervised living. Individuals with a higher level of positive symptoms were less likely to live independently. The educational status of the subjects was also a correlate of the dwelling status in this study. Those living independently had an average of 12.1 years of education, while those living in a supervised setting had an average of 10.9 years of education.

These data reveal that MMSE scores and levels of negative symptoms may be used to determine the nature of the dwelling the patient should have after hospital discharge. Future research should attempt to articulate the ranges of cognitive function that are compatible with different residential placements.

|

Presented in part at the 13th annual meeting of the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry, Miami, March 24–26, 2000. Received Oct. 18, 2001; revision received May 30, 2002; accepted June 6, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, Olean General Hospital; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Buffalo, N.Y.; Women’s Christian Association Hospital, Jamestown, N.Y.; Global Research and Consulting, Olean, N.Y.; and the Continuing Day Treatment Program, Olean, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Gupta, 515 Main St., Olean, NY 14760; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-49671. The authors thank Dilip Jeste, M.D., and Lisa Auslander, Ph.D., for comments on this article.

1. Cohen CI, Cohen GD, Blank K, Gaitz C, Katz IR, Leuchter A, Maletta G, Meyers B, Sakauye K, Shamoian C: Schizophrenia and older adults, an overview: directions for research policy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 8:19-28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Evans JD, Negron AE, Palmer BW, Paulsen JS, Heaton RK, Jeste DV: Cognitive deficits and psychopathology in hospitalized versus community-dwelling elderly schizophrenia patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1999; 12:11-15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Auslander LA, Lindamer LL, Delapena J, Harless K, Polichar D, Patterson TL, Zisook S, Jeste DV: A comparison of community-dwelling older schizophrenia patients by residential status. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 103:380-386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799-812Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

7. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adeey M, Leirer VO: Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1983; 17:37-49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

9. Hedges LV, Olkin I: Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. New York, Academic Press, 1985Google Scholar

10. Mattis S: Dementia Rating Scale. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1973Google Scholar