Fatigue in Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Driven by Depressive Symptoms Instead of Apnea Severity?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Obstructive sleep apnea is a common and frequently devastating illness that often includes significant fatigue. Fatigue is also a hallmark depressive symptom. The authors wondered if depressive symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea would account for some of the fatigue beyond that explained by obstructive sleep apnea severity. METHOD: Sixty patients with obstructive sleep apnea—i.e., score ≥15 on the respiratory disturbance index (mean score=49; range=15–111)—underwent polysomnography and completed the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale), Profile of Mood States (POMS), and Medical Outcomes Study surveys. Data were analyzed by using hierarchical regression, with POMS fatigue score as the dependent variable (step 1, forced entry of apnea severity variables; step 2, forced entry of CES-D Scale score). RESULTS: Whereas score on the respiratory disturbance index and the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% together accounted for 4.2% of variance in scores on the POMS fatigue scale, the CES-D Scale score accounted for 10 times the variance (i.e., an additional 42.3%) in POMS fatigue scale score. CONCLUSIONS: After obstructive sleep apnea severity was controlled, higher levels of depressive symptoms were dramatically and independently associated with greater levels of fatigue. Assessment and treatment of mood symptoms—not just treatment of the disordered breathing itself—might reduce the fatigue experienced by patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

The interplay of fatigue and depression in chronic illness is a topic that pervades much of medicine. However, the literature is rather limited when it comes to understanding the separate effects of illness severity and mood on the patient’s experience of fatigue. We wondered about the relationship among these constructs in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Affecting up to 9% of middle-aged adults (with higher percentages in the elderly), obstructive sleep apnea is a potentially devastating illness that involves chronic sleep loss and associated hypoxia (1–4).

During the night, patients with obstructive sleep apnea experience multiple episodes in which the airway collapses and breathing stops—over 100 events per hour in severe cases—resulting in repeated arousals.

Patients with obstructive sleep apnea frequently complain of both fatigue and sleepiness. Although these terms are sometimes used interchangeably and are both associated with diminished quality of life and curtailment of daytime activities, there are conceptual differences. Sleepiness, or the propensity to fall asleep, is believed to reflect a physiological need for sleep and is objectively quantifiable with a daytime test such as the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (5) or the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (6). On these tests, patients with obstructive sleep apnea consistently score in the “very sleepy” range. For example, on the Multiple Sleep Latency Test, healthy adults show mean time to sleep onset of 10–20 minutes. Adults with times of 5–6 minutes are considered “very (pathologically) sleepy.” Fatigue, on the other hand, is a terribly common but poorly understood complaint in obstructive sleep apnea (7) and many other chronic illnesses (8–37). Fatigue encompasses physical and psychological factors as well as social and cultural influences. The conceptual borders of fatigue are ill defined and shade into areas such as tiredness, decreased strength, lack of energy, lethargy, and difficulty with concentration. Like pain, fatigue is a symptom that is nearly always assessed by self-report. For this investigation we relied on the fatigue-inertia subscale of the Profile of Mood States (POMS), which defines fatigue as “a mood of weariness, inertia, and low energy level” (38).

Fatigue is also a common component of mood disorders and is one of the diagnostic symptoms of major depression. There is a substantial body of research that examines the interplay of fatigue and mood in chronic illnesses. One might assume that fatigue and mood would worsen in tandem as disease severity progresses. However, findings are conflicting, even when disease severity is taken into account.

We found 31 studies that directly addressed the relationship between fatigue and depressive symptoms in illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, and rheumatological disorders. Nearly all of these studies reported a significant positive relationship between fatigue and depression (8–12, 14–22, 24–33, 35, 37, 39). One-third found significant relationships between fatigue and illness severity (11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 23, 30, 32, 34, 39), whereas several did not (21, 23, 25, 31, 33, 35, 36). Only three studies reported a significant association between depression and illness severity (13, 23, 39). Four studies reported that the fatigue-depressive symptom relationship remained significant after illness severity was controlled (10, 17, 22, 26).

Most studies of the relationship between fatigue and depressive symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea focus on the change in mood symptoms after treatment. While several authors have reported improvement in both fatigue and depressive symptoms (39, 40), findings are less clear when a placebo-controlled design is employed (40).

In summary, while the bulk of the evidence suggests that fatigue and depressive symptoms are positively associated, there are relatively few studies that have examined the relationship between fatigue and depressive symptoms after having controlled for disease severity. Therefore, it is difficult to tease out the separate effects of physical illness and mood on the experience of fatigue. Some of the disparity in findings may be due, in part, to the variety of fatigue and depression measures used. Additional reasons for discrepancies include the fact that most studies did not control for illness severity variables and because relationships between fatigue and depressive symptoms may vary depending on the illness being studied.

We hypothesized that depressive symptoms would account for a significant portion of the fatigue experienced by patients with obstructive sleep apnea—beyond that explained by sleep disruption and hypoxia. Much of the previous research into mood and sleep disturbance has focused on patients with diagnosed affective disorders. However, there is a growing interest in the quality of life impact of depressive symptoms that fall below the threshold of a diagnosable disorder. For this reason, we looked at the relationship between depressive symptoms and fatigue by using a continuous measure of depressive symptoms in a nonpsychiatric group of patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Method

Sixty patients with obstructive sleep apnea were recruited by advertising and word of mouth to participate in our research on sympathetic nervous system physiology in obstructive sleep apnea. To qualify, participants had to be 100%–150% of ideal body weight per Metropolitan Life Insurance tables (41). Although obstructive sleep apnea is more common among the obese, participants >150% of ideal body weight were excluded because of the possibility of confounding by other conditions associated with obesity. Potential participants were also excluded if they had major medical illnesses other than obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension. The protocol was approved by the University of California, San Diego, Human Subjects Committee. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Participants had their sleep monitored for an entire night in the General Clinical Research Center with a standard regimen of polysomnography: central and occipital EEG, bilateral electro-oculogram, submental and bilateral tibialis electromyogram, nasal/oral airflow (using a thermistor), and thoracic and abdominal excursions with Respitrace respiratory inductive plethysmography. Oxygen saturation was monitored by using a pulse oximeter (Biox 3740, Datex-Ohmeda, Louisville, Colo.) and was analyzed by using computer software (Profox Associates, Inc., Escondido, Calif.). The oxygen saturation variable selected as indicative of obstructive sleep apnea severity was percent of time that oxygen saturation was <90%.

Sleep recordings were scored according to the criteria of Rechtschaffen and Kales (42). Apneas were defined as decrements in airflow of ≥90% from baseline for ≥10 seconds. Hypopneas were defined as decrements in airflow of ≥50% but <90% from baseline for ≥10 seconds (43). The majority of subjects had solely obstructive type events; only a few subjects showed evidence of central apneas. Potential participants who showed predominant central apneas (>50% of total apneas) were excluded. The number of apneas and hypopneas per hour were calculated to obtain the respiratory disturbance index. Obstructive sleep apnea was defined as a score on the respiratory disturbance index ≥15.

Participants completed the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale) (44), the POMS (38), and Medical Outcomes Study surveys (45). The CES-D Scale is a frequently used 20-item self-report scale that has been shown to be reliable and valid for assessing depressive symptoms (44). In a variety of populations, a large percentage of subjects with a score ≥16 have been shown to meet diagnostic criteria for dysthymia or major depression (46, 47). When used with medically ill patients, depression rating scales are sometimes influenced by illness symptoms. For example, mood-related observations in patients with obstructive sleep apnea could be confounded by fatigue or sleepiness. However, the CES-D Scale primarily taps cognitive/affective aspects of depression and has been shown to be useful in chronically ill groups experiencing fatigue (e.g., HIV, cancer) (48, 49), including obstructive sleep apnea patients (50, 51).

The POMS is a well-established, factor-analytically derived measure of psychological distress for which high levels of reliability and validity have been documented (38). The POMS consists of 65 adjectives rated on a 0–4 scale that can be consolidated into six subscales: fatigue-inertia, depression-dejection, vigor-activity, tension-anxiety, anger-hostility, and confusion-bewilderment. The POMS has been used in a variety of chronically ill and well populations (38, 52–58), including obstructive sleep apnea patients (40, 59, 60). We were particularly interested in the fatigue-inertia subscale. This subscale measures weariness, inertia, and low energy level—states commonly experienced by patients with obstructive sleep apnea—and has been validated as a separate factor in several studies. Norms have been published for a variety of patient and nonpatient groups (38).

Data were analyzed by using SPSS 10.0 software (1999) hierarchical linear regression with POMS fatigue subscale score as the dependent variable: step 1, forced entry of obstructive sleep apnea severity variables (score on the respiratory disturbance index, the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% ); step 2, forced entry of CES-D Scale score. Because depression and fatigue overlap, the analysis was rerun after excluding three fatigue-related CES-D Scale items (item 7: “…everything I did was an effort”; item 11: “…sleep was restless”; and item 20: “…could not get going) (44). Findings were similar, so results using the full CES-D Scale are reported.

We also analyzed the data by using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) approach. A cutoff score of 16 on the CES-D was used to dichotomize the patient group into those with high (i.e., ≥16) versus low (i.e., <16) scores. In addition, we used median values to split the patient group into high versus low respiratory disturbance index (median=40) groups and high versus low percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% (median=10%) groups. ANCOVA was then conducted to see if the high versus low groups for CES-D Scale score, respiratory disturbance index, and oxygen saturation differed in terms of POMS fatigue subscale score. All tests were two-tailed. We also reran the analyses substituting the energy/fatigue subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study surveys (45) for the POMS fatigue subscale and the POMS depression subscale for the CES-D Scale.

Results

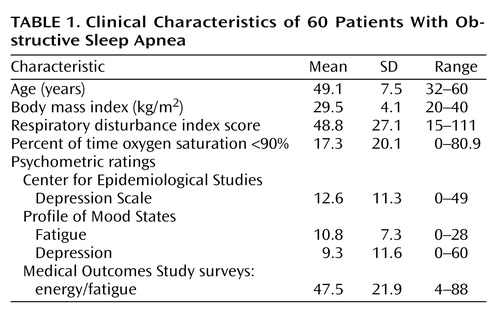

Subjects included 51 men and nine women (five African American, one Asian, 40 Caucasian, 12 Hispanic, two “other” ethnicities) whose average age was 49.1 years. Other clinical characteristics of the patient group are presented in Table 1. One-third of the subjects had a CES-D Scale score ≥16.

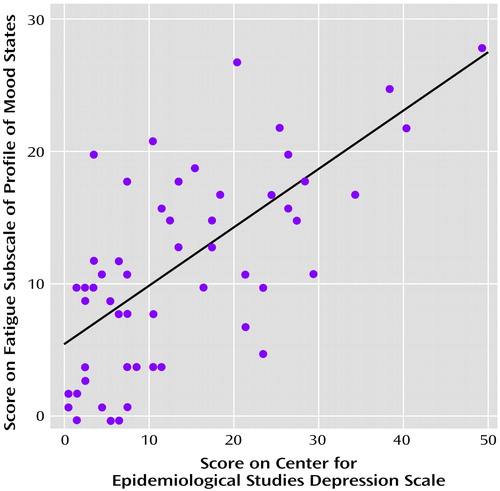

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for POMS fatigue subscale score versus obstructive sleep apnea severity variables and CES-D Scale score. Score on the respiratory disturbance index (r=0.11, df=58, p<0.42) and the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% (r=0.20, df=58, p=0.12) were not significantly correlated with POMS fatigue subscale scores, but CES-D Scale score was (r=0.68, df=58, p<0.001).

We analyzed these data by using multiple statistical approaches to ascertain how robust these findings are. Specifically, we examined the additive effect of depressive symptoms on fatigue after we controlled for obstructive sleep apnea severity by using both multiple regression and ANCOVA. We also tested the models by using different fatigue and depressive symptom measures. As the following paragraphs make clear, the findings are substantially the same—depressive symptoms far outweigh obstructive sleep apnea severity in accounting for fatigue.

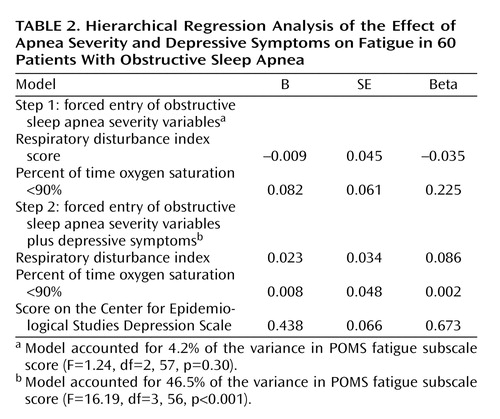

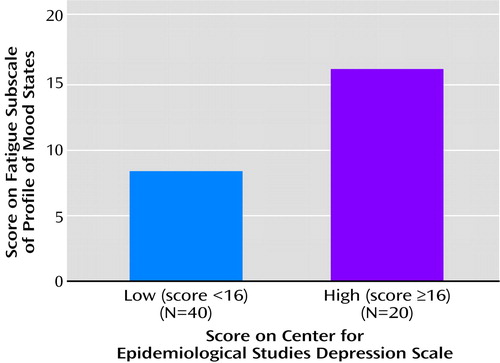

Results of the hierarchical linear regression analysis were significant (Table 2). While score on the respiratory disturbance index and the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% together accounted for 4.2% of the variance in POMS fatigue subscale score, the CES-D Scale score accounted for an additional 42.3%. In the ANCOVA, after the apnea severity variables were controlled, significantly more fatigue was seen in patients in the high CES-D Scale score group (mean=16.2, SD=6.4) than in the low CES-D Scale score group (mean=8.4, SD=6.3) (Figure 1). Analyses of variance that compared the high versus low groups for either respiratory disturbance index score or the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90% were not significant in predicting POMS fatigue subscale scores.

We reran the hierarchical model using the POMS depression subscale in place of the CES-D and the energy/fatigue subscale from the Medical Outcomes Study surveys in place of the POMS fatigue subscale. Results remained essentially the same.

Discussion

Whether a result of chronic medical illness or disturbance of mood, fatigue can have a devastating impact on quality of life. The sleep literature cites fatigue as a common sequela of obstructive sleep apnea. In obstructive sleep apnea patients with depressive symptoms, it has been unclear to what degree the obstructive sleep apnea severity and mood disturbance contribute to the fatigue experienced. We hypothesized that depressive symptoms would account for a significant amount of the fatigue reported in obstructive sleep apnea patients after apnea severity was controlled. Our findings strongly support this hypothesis.

Simple correlations revealed that depressive symptoms, but not obstructive sleep apnea severity, were significantly associated with self-reported fatigue. However, we took a conservative approach and included the obstructive sleep apnea severity variables in the analyses before testing the relationship between the CES-D Scale and POMS fatigue subscale scores. Results revealed that depressive symptoms accounted for 10 times the amount of variance in fatigue in obstructive sleep apnea patients as did apnea severity (as measured by respiratory disturbance index score and the percent of time oxygen saturation was <90%). To determine if these relationships were consistent across the spectrum of depressive symptoms, we plotted CES-D Scale scores against POMS fatigue, revealing a fairly steady positive dose-response relationship for depressive symptoms (Figure 2). Furthermore, after controlling for obstructive sleep apnea severity, patients likely to have a mood disorder (CES-D Scale score ≥16) reported twice as much fatigue as patients reporting fewer depressive symptoms (Figure 1). These relationships proved to be remarkably robust—the same pattern of findings emerged when substituting other measures of fatigue and depressive symptoms. Results held even after eliminating fatigue-related items on the CES-D Scale, so they cannot be explained by symptom overlap.

Limitations

Our subject population came primarily from advertisements and may not be representative of the type of patients seen in the sleep disorders clinic. Nevertheless, the severity of obstructive sleep apnea was equivalent to that seen in the clinic. The ethnic distribution of our patient group was representative of the population in San Diego County. However, because data on ethnicity in obstructive sleep apnea are limited, we cannot be certain that our patient group reflects the ethnic distribution of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population.

We relied on subject self-reports to gauge fatigue and depressive symptoms, and such instruments are often influenced by response bias. However, we reran the analyses after controlling for scores on the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale, a common measure of response bias (61). The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale did not contribute significantly to the regression or ANCOVA models (p=0.833 and p=0.283, respectively), and interpretation of findings did not change when it was included.

Because our design was cross-sectional, we cannot determine direction of causality between depressive symptoms and fatigue. It is possible that fatigue causes depressive symptoms. However, obstructive sleep apnea severity was not directly related to fatigue. Therefore, if fatigue causes depression, our findings suggest it would be the result of factors other than obstructive sleep apnea severity.

While we relied on the CES-D Scale, the structured clinical interview is the gold standard for assessing depressive symptoms. However, we were less interested in determining the presence of a diagnosable mood disorder than in assessing the mood-fatigue relationship across a spectrum of depressive symptoms. The CES-D Scale is one of the more reliable and valid instruments for this purpose. Findings were essentially the same when substituting the POMS depression scale.

Conclusions

These results suggest that it is depressive symptoms rather than respiratory disturbance or oxygen saturation levels that account for the fatigue experienced by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. This mood-fatigue relationship is consistent across a wide range of depressive symptoms. We conclude that depressive symptoms must be considered in studies of fatigue in obstructive sleep apnea. From a clinical perspective, the assessment and treatment of mood disorders—not just the disordered breathing itself—might have major potential to reduce the fatigue experienced in obstructive sleep apnea. These findings also demonstrate the importance of considering subthreshold levels of depressive symptoms in patients living with chronic illness.

|

|

Received Jan. 14, 2002; revision received May 9, 2002; accepted July 25, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego; and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego. Address reprint requests to Dr. Bardwell, Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0804; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIH grants HL-44915, RR-00827, AG-08415, and CA-85264.

Figure 1. Severity of Fatigue in 60 Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea by Level of Depressive Symptoms After Apnea Severity Was Controlleda

aSignificant effect of group (F=19.79, df=3, 56, p<0.001).

Figure 2. Relationship Between Level of Depressive Symptoms and Severity of Fatigue in 60 Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apneaa

ar=0.68, df=58, p<0.001.

1 . Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Mason WJ, Fell R, Kaplan O: Sleep disordered breathing in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep 1991; 14:486-495Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 . Jennum P, Sjol A: Epidemiology of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea in a Danish population, age 30-60. J Sleep Res 1992; 1:240-244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 . Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S: The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:1230-1235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 . Orr WC: Sleep apnea, hypoxemia, and cardiac arrhythmias. Chest 1986; 89:1-2Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 . Mitler M, Gujavarty K, Browman C: Maintenance of Wakefulness Test: a polysomnographic technique for evaluation of treatment efficacy in patients with excessive somnolence. EEG Clin Neurophysiol 1982; 53:658-661Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 . Carskadon MA, Dement WC, Mitler MM, Roth T, Westbrook PR, Keenan S: Guidelines for the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT): a standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep 1986; 9:519-524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 . Odens ML, Fox CH: Adult sleep apnea syndromes. Am Fam Physician 1995; 52:859-866Medline, Google Scholar

8 . Valentine AD, Meyers CA: Cognitive and mood disturbance as causes and symptoms of fatigue in cancer patients. Cancer 2001; 92(suppl 6):1694-1698Google Scholar

9 . Badger TA, Braden CJ, Mishel MH: Depression burden, self-help interventions, and side effect experience in women receiving treatment for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001; 28:567-574Medline, Google Scholar

10 . Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR: Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18:743-753Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 . Stone P, Richards M, A’Hern R, Hardy J: A study to investigate the prevalence, severity and correlates of fatigue among patients with cancer in comparison with a control group of volunteers without cancer. Ann Oncol 2000; 11:561-567Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 . Redeker N, Lev EL, Ruggiero J: Insomnia, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and quality of life of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Sch Inq Nurs Pract 2000; 14:275-290Medline, Google Scholar

13 . Glaus A, Muller S: Hemoglobin and fatigue in cancer patients: inseparable twins? Schweiz Med Wochenschr 2000; 130:471-477Medline, Google Scholar

14 . Gaston-Johansson F, Fall-Dickson JM, Bakos AB, Kennedy MJ: Fatigue, pain, and depression in pre-autotransplant breast cancer patients. Cancer Pract 1999; 7:240-247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 . Visser MR, Smets EM: Fatigue, depression and quality of life in cancer patients: how are they related? Support Care Cancer 1998; 6:101-108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 . Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Martin SC, Kronish LE, Azzarello LM, Fields KK: Fatigue in women treated with bone marrow transplantation for breast cancer: a comparison with women with no history of cancer. Support Care Cancer 1997; 5:44-52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 . Fifield J, McQuillan J, Tennen H, Sheehan TJ, Reisine S, Hesselbrock V, Rothfield N: History of affective disorder and the temporal trajectory of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Behav Med 2001; 23:34-41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 . Tench CM, McCurdie I, White PD, D’Cruz DP: The prevalence and associations of fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2000; 39:1249-1254Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 . Barendregt PJ, Visser MR, Smets EM, Tulen JH, van den Meiracker AH, Boomsma F, Markusse HM: Fatigue in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 1998; 57:291-295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 . Smedstad LM, Moum T, Vaglum P, Kvien TK: The impact of early rheumatoid arthritis on psychological distress: a comparison between 238 patients with RA and 116 matched controls. Scand J Rheumatol 1996; 25:377-382Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 . Wang B, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB: Fatigue in lupus is not correlated with disease severity. J Rheumatol 1998; 25:892-895Medline, Google Scholar

22 . McKinley PS, Ouellette SC, Winkel GH: The contributions of disease activity, sleep patterns, and depression to fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a proposed model. Arthritis Rheum 1995; 38:826-834Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 . Croft P, Schollum J, Silman A: Population study of tender point counts and pain as evidence of fibromyalgia. Br Med J 1994; 309:696-699Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 . Ferrando S, Evans S, Goggin K, Sewell M, Fishman B, Rabkin J: Fatigue in HIV illness: relationship to depression, physical limitations, disability. Psychosom Med 1998; 60:759-764Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 . Dwight MM, Kowdley KV, Russo JE, Ciechanowski PS, Larson AM, Katon WJ: Depression, fatigue, and functional disability in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Psychosom Res 2000; 49:311-317Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 . van der Werf SP, van den Broek HLP, Anten HWM, Bleijenberg G: Experience of severe fatigue long after stroke and its relation to depressive symptoms and disease characteristics. Eur Neurol 2001; 45:28-33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 . Wojciechowski FL, Strik JJ, Falger P, Lousberg R, Honig A: The relationship between depressive and vital exhaustion symptomatology post-myocardial infarction. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:359-365Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 . Appels A, Kop WJ, Schouten E: The nature of the depressive symptomatology preceding myocardial infarction. Behav Med 2000; 26:86-89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 . Irvine J, Basinski A, Baker B, Jandciu S, Paquette M, Cairns J, Connolly S, Rogberts R, Gent M, Dorian P: Depression and risk of sudden cardiac death after acute myocardial infarction: testing for the confounding effects of fatigue. Psychosom Med 1999; 61:729-737Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 . Kopp MS, Falger PR, Appels A, Szedmak S: Depressive symptomatology and vital exhaustion are differentially related to behavioral risk factors for coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med 1998; 60:752-758Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 . Denollet J: Emotional distress and fatigue in coronary heart disease: the Global Mood Scale (GMS). Psychol Med 1993; 23:111-121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 . Kroencke DC, Lynch SG, Denney DR: Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: relationship to depression, disability, and disease pattern. Mult Scler 2000; 6:131-136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 . Bakshi R, Shaikh ZA, Miletich RS, Czarnecki D, Dmochowski J, Henschel K, Janardhan V, Dubey N, Kinkel PR: Fatigue in multiple sclerosis and its relationship to depression and neurologic disability. Mult Scler 2000; 6:181-185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 . Mendes MF, Tilbery HP, Balsimell S, Felipe E, Moreira MA, Barao-Cruz AM: Fatigue in multiple sclerosis relapsing-remitting form. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2000; 58:471-475Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 . Ford H, Trigwell P, Johnson M: The nature of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res 1998; 45:33-38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 . Vercoulen JH, Hommes OR, Swanink CM, Jongen RJ, Fennis JF, Galama JM, van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G: The measurement of fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: a multidimensional comparison with patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and healthy subjects. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:642-649Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 . Johnson SK, DeLuca J, Natelson BH: Chronic fatigue syndrome: reviewing the research findings. Ann Behav Med 1999; 21:258-271Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 . McNair PM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF: POMS Manual: Profile of Mood States. San Diego, Calif, Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1992Google Scholar

39 . Derderian SS, Bridenbaugh RH, Rajagopal KR: Neuropsychologic symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea improve after treatment with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Chest 1988; 94:1023-1027Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 . Yu BH, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE: Effect of CPAP treatment on mood states in patients with sleep apnea. J Psychiatr Res 1999; 33:427-432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 . Metropolitan Life Insurance Company: 1983 Metropolitan height and weight tables. Stat Bull Metrop Life Found 1983; 64:3-9Medline, Google Scholar

42 . Rechtshaffen A, Kales A (eds): A Manual of Standardized Terminology: Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Los Angeles, UCLA Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute, 1968Google Scholar

43 . Loredo JS, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE: Effect of continuous positive airway pressure vs placebo continuous positive airway pressure on sleep quality in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 1999; 116:1545-1549Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 . Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Applied Psychol Measurement 1977; 1:385-401Crossref, Google Scholar

45 . Stewart AL, Ware JE: Measuring Functioning and Well-Being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 1992Google Scholar

46 . Murphy J: Psychiatric instrument development for primary care research: patient self-report questionnaire, report on contract 80M01428101D. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1982Google Scholar

47 . Schulberg H, Saul M, McClelland M, Ganguli M, Christy W, Frank R: Assessing depression in primary medical and psychiatric practices. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:1164-1170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 . Cockram A, Judd FK, Mijch A, Norman T: The evaluation of depression in inpatients with HIV disease. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1999; 33:344-352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 . Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P: Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). J Psychosom Res 1999; 46:437-443Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50 . Bardwell WA, Berry CC, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE: Psychological correlates of sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res 1999; 47:583-596Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 . Bardwell WA, Moore P, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE: Does obstructive sleep apnea confound sleep architecture findings in subjects with depressive symptoms? Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:1001-1009Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 . Cella DF, Tross S, Orav EJ, Holland JC, Silberfarb PM, Rafla S: Mood states of patients after the diagnosis of cancer. J Psychosocial Oncology 1989; 7:45-54Crossref, Google Scholar

53 . DiLorenzo TA, Bovberg DH, Montgomery GH, Valdimarsdottir H, Jacobsen PB: The application of a shortened version of the profile of mood states in a sample of breast cancer chemotherapy patients. Br J Health Psychol 1999; 4:315-325Crossref, Google Scholar

54 . Holland JC, Korzun AH, Tross S, Siberfarb P, Perry M, Comis R, Oster M: Comparative psychological disturbance in patients with pancreatic and gastric cancer. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:982-986Link, Google Scholar

55 . Shumaker SA, Anderson RT, Czajkowski SM: Psychological tests and scales, in Quality of Life Assessments in Clinical Trials. Edited by Spilker B. New York, Raven Press, 1990, pp 95-114Google Scholar

56 . Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I: Group support for patients with metastatic cancer: a randomized prospective outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:527-533Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57 . Taylor SE, Lichtmain RR, Wood JV: Attributions, beliefs about control and adjustment to breast cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol 1984; 46:486-501Crossref, Google Scholar

58 . Taylor SE, Lichtmain RR, Wood J, Bluming A, Dosik G, Leibowitz R: Illness and treatment-related factors in psychological adjustment to breast cancer. Cancer 1985; 55:2503-2513Crossref, Google Scholar

59 . Dickel MJ, Mosko SS: Morbidity cut-offs for sleep apnea and periodic leg movements in predicting subjective complaints in seniors. Sleep 1990; 13:155-166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60 . Mosko S, Zetin M, Glen S, Garber D, DeAntonio M, Sassin J, McAnich J, Warren S: Self-reported depressive symptomatology, mood ratings, and treatment outcome in sleep disorders patients. J Clin Psychol 1989; 45:51-60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61 . Crowne DP, Marlowe DA: A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. J Consult Psychol 1960; 24:349-354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar