Clinical Characteristics, 4-Year Course, and DSM-IV Classification of Patients With Nonaffective Acute Remitting Psychosis

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the clinical characteristics and 48-month illness course of cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis and described the classification of these cases in the DSM-IV system. METHOD: The data were derived from the Suffolk County (N.Y.) Mental Health Project, a study of first-admission patients with psychotic disorders admitted to psychiatric facilities between September 1989 and December 1995. The authors compared the demographic and clinical characteristics, 48-month course, and longitudinal research diagnoses of 16 patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis, defined by onset in 2 weeks or less and duration of less than 6 months, to those of 26 patients with other nonaffective remitting psychoses. RESULTS: Nonaffective acute remitting psychosis had a distinctly benign course—46% of the patients remained in full remission throughout the 48-month follow-up, compared with 14% of patients with other remitting psychoses. Nonaffective acute remitting psychosis was also associated with fewer negative symptoms than other remitting psychoses. By 24-month follow-up, only 6% of the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis, compared with 77% of the patients with other remitting psychoses, received a research diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, whereas 44% of patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis, compared with 12% of patients with other remitting psychoses, were given the residual diagnosis of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. CONCLUSIONS: Nonaffective acute remitting psychosis is a highly distinctive yet not adequately classified condition. Better delineation of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis in current diagnostic systems could lead to better understanding of this condition and improve the applicability of diagnostic systems in developing countries, where these conditions are more common than in industrialized countries.

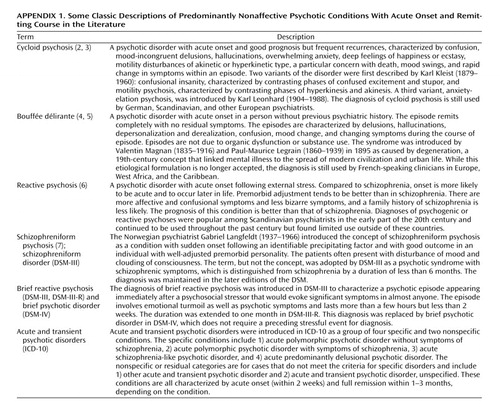

This study examined the characteristics and the DSM-IV diagnoses of cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis in the Suffolk County Mental Health Project, an epidemiological study of first-admission patients with psychotic disorders. Along with the classic descriptions of schizophrenia and affective psychoses, a separate group of nonaffective psychoses with a more benign course than schizophrenia has been recognized and variously described. Kraepelin (1) classified these psychoses under the category of amentia, a condition first described by Meynert as a benign psychosis associated with confusion and sensory and motor symptoms. Later European psychopathologists described a similar condition using various terms (Appendix 1) (2–7). Each description emphasized different features that were regarded as central. Nevertheless, the various descriptions shared certain common features, such as acute onset, brief duration, benign outcome in the long run, and higher prevalence among females than among males. Based on these common features, we (8), along with other authors (9), proposed classifying these cases using a category of disorders with readily discernible features of acute onset (i.e., onset of psychosis within a 2-week period) and brief duration (not longer than 6 months). To distinguish these cases from episodes of affective psychosis, which also could present with acute onset and brief duration, we introduced the additional criterion of nonaffective illness. Hence we called this category “nonaffective acute remitting psychosis.”

Our previous studies of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis (10–14) suggested unique features. In an analysis of the data from the World Health Organization (WHO) Ten Country Study, we reported that nonaffective acute remitting psychosis was 10 times more common in developing than in industrialized countries and two times more common in females than males (10). The data from another WHO study (the India site of the Acute Psychosis Study) suggested that nonaffective acute remitting psychosis is distinguishable from schizophrenia with acute onset on the basis of a bimodal distribution of duration (11). In a 15-year follow-up at an Indian site of the Ten Country Study, the cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis exhibited a highly distinctive benign long-term course (13).

Despite distinctive features, the place of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis in modern classifications of mental disorders remains uncertain. ICD-10 came closest to the historical concept of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis by introducing the group of acute and transient psychotic disorders, which includes four specific disorders and two nonspecific disorders. However, the ICD-10 characterization of acute remitting psychosis is problematic. First, the duration criterion is so restrictive that many cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis do not fit the criteria for the acute and transient psychotic disorders (14, 15). Second, as stated in ICD-10, there is little evidence to support the proposed subclassification of acute and transient psychotic disorders into specific disorders.

The place of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis in the other major classification system, DSM-IV, is less clear. In DSM-IV, cases of nonaffective psychosis with brief duration are classified into two categories—schizophreniform disorder and brief psychotic disorder. Cases that last less than 1 month are categorized as brief psychotic disorder. Among cases that last more than 1 month but less than 6 months, only those that meet criterion A for schizophrenia are categorized as schizophreniform disorder. Psychoses with a brief duration that do not meet the specific criteria for these disorders—for instance, psychoses that last longer than 1 month but do not meet criterion A for schizophrenia—are generally relegated to the residual category of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. Furthermore, acute onset is not a criterion for brief psychotic disorder or schizophreniform disorder. Thus, these diagnoses lump together cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis, as well as cases of remitting psychosis with nonacute onset and typical cases of schizophrenia and other persistent psychoses in their early course. Perhaps as a result of this heterogeneity, these diagnoses have proved unstable over time (16).

The present report is part of a series of reports on delineation of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis (10–14) and extends our earlier work based on the 24-month follow-up of the first half of the Suffolk County Mental Health Project sample (12). In the present report, we use data from the full sample of the Suffolk County Mental Health Project, extend the follow-up to 48 months, use DSM-IV diagnoses, and examine a broader set of clinical variables, including age at onset, severity of negative and positive symptoms, symptoms of emotional turmoil and confusion, and treatment course. We first compare the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis with the characteristics of cases of nonaffective remitting psychoses with nonacute onset, henceforth called “other remitting psychoses,” and, second, examine the illness course and DSM-IV classification of these two groups.

Method

Suffolk County Mental Health Project Design

The Suffolk County Mental Health Project is an ongoing longitudinal study of consecutive first-admission patients with psychotic disorders admitted to one of the 12 psychiatric facilities in Suffolk County, N.Y., between September 1989 and December 1995. The inclusion criteria were age 15–60 years, residency within the county, and clinical evidence of psychosis (16, 17). Exclusion criteria were a psychiatric hospitalization more than 6 months before current admission, moderate or severe mental retardation, and inability to speak English. The initial response rate was 72%. Overall, 674 individuals who met the inclusion criteria were interviewed at baseline. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after the interview procedure had been fully explained. After the baseline interview, the participants were followed-up and interviewed at 6, 24, and 48 months. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. For minors, informed consent was also obtained from parents. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the State University of New York at Stony Brook and each participating facility.

Sample for This Study

The sample for this study comprised cases of nonaffective remitting psychoses. Nonaffective remitting psychoses were defined as psychotic disorders with no affective diagnoses at baseline or at 6-month or 24-month follow-up and a rating of full remission of psychosis at the 6-month follow-up. The sample was further subdivided into cases with an acute onset (nonaffective acute remitting psychosis) and cases with nonacute onset (other remitting psychoses). This sample was drawn from 323 cases in the Suffolk County Mental Health Project of nonorganic, non-substance-induced psychoses with a nonaffective diagnosis (diagnoses other than bipolar disorder, major depression, and schizoaffective disorder) at baseline and with complete information on mode of onset and 6-month remission status.

Ratings

Mode of onset

We used the WHO mode of onset rating (18), found to be reliable in previous studies (10). The ratings were reached by consensus after the 24-month follow-up and could include 1, for onset within 1 week without prodrome; 2, for onset within 1 week with prodrome; 3, for onset within 1 month; 4, for onset within a period longer than 1 month; and 5, for no clear demarcation between premorbid personality and mental illness.

To conform to the ICD-10 onset criterion for acute and transient psychotic disorders, we defined acute onset as “a change from a state without psychotic features to a clearly abnormal psychotic state, within a period of 2 weeks or less” (p. 99). All participants who received a mode-of-onset rating of 1 on the WHO instrument met this ICD-10 criterion. Participants with a mode-of-onset rating of 2 or 3 had to be rerated in terms of the ICD-10 criterion as previously described (12). Participants with other modes of onset were categorized as having a nonacute onset.

Remission at 6-month follow-up

At 6-month follow-up, interviewers completed summary ratings of remission. For this study, ratings of “no psychotic symptoms—full remission within 3 months” and “no psychotic symptoms—full remission between 3 and 6 months” were defined as full remission. Evaluation of these ratings in a previous analysis showed them to be valid (12). By using these ratings, 42 (13.0%) of the 323 cases with nonaffective psychosis in this sample were classified as remitted at 6-month follow-up. Remission rates vary considerably across studies of first admissions with psychotic disorders (18–21), and while the remission rate in this study was in the lower range compared to most other studies, it is consistent with that previously reported for schizophrenia in the first half of the Suffolk County Mental Health Project sample (22).

Ratings of illness course

A standardized rating of course of illness developed by WHO, which has been used in previous studies and found to be reliable (18), was completed at the 24-month consensus meeting. The ratings included information on the number of psychotic and nonpsychotic episodes since the onset of disorder and the level of remissions (if any) between episodes. A rating of full remission between episodes required that the participant be symptom-free for at least 4 weeks. Course of illness was also rated at 48-month follow-up by using a similar procedure.

Symptom severity

At baseline and at each follow-up the interviewers completed the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (23, 24).

Emotional turmoil and confusion

A common feature in classic descriptions of acute remitting psychosis is emotional turmoil and confusion. These features were included as a criterion for the diagnosis of brief reactive psychosis in DSM-III-R. In the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (25), the rating of this criterion was operationalized by one question assessing “rapid shifts from one intense affect to another, or overwhelming perplexity or confusion.” For this report, rating of these was based on the baseline interview.

Age at onset

Assessment of age at onset was based on information in medical records and interviews with the participant and relatives. Age at onset was defined as the age when the participant experienced the first full-blown psychotic symptom. Consensus decisions about age at onset were made at the 24-month consensus meeting.

Treatment

Course of treatment from intake to the 24-month follow-up was determined at the consensus meeting by using all available information to that point. A similar assessment of course of treatment covering the 24–48-month period was done at 48 months by the interviewer. For this study, we analyzed the number of months the patient received any form of treatment and number of months the patient received antipsychotic medications.

Diagnosis

At baseline and at each face-to-face follow-up encounter, participants were interviewed with the SCID (25). The reliability of the SCID ratings has been previously reported (17). After completing the baseline evaluation with the SCID, two project psychiatrists independently reviewed all available information, including data from the SCID and from other research assessments, medical records, and the interviewer’s detailed narrative of the case. They then independently reached an initial DSM-III-R diagnosis; when they disagreed, a consensus process was used. After completion of the 6-month follow-up SCID, two project psychiatrists again independently reviewed all available information and then together tried to reach an agreement on a DSM-IV diagnosis. Their diagnosis (or diagnoses) and the rationale for it (them) were presented and debated at a diagnostic meeting of all investigators and the research coordinator. The consensus decision of the diagnostic meeting was the final 6-month diagnosis. The 24-month diagnostic protocol was similar to the 6-month protocol. However, the interviewer joined the two psychiatrists in formulating a diagnosis and participated in the 24-month consensus meeting. The team at the 24-month consensus meeting was not informed of the 6-month diagnosis before making the 24-month diagnosis. This consensus meeting also determined the WHO mode of onset and course ratings described earlier.

Data Analysis

Cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis were compared to cases of other remitting psychoses on gender differences in age at onset and on course of illness by using contingency table analysis and binary logistic regression for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. The course of symptoms from baseline to the 6-month and 24-month follow-ups was examined by using the method of generalized estimating equations, which accommodates missing data (26). Data on SANS and SAPS were available for only five cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis at 48-month follow-up. Therefore, these comparisons were not extended to the 48-month follow-up. To examine the diagnoses of these cases under DSM-IV, we tabulated the 6- and 24-month DSM-IV research diagnoses across the two groups.

Results

Prevalence

Among the 323 cases of nonaffective psychoses, 16 (5%) met the criteria for nonaffective acute remitting psychosis and 26 (8%) met the criteria for other remitting psychoses. The 16 cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis represented 38% of the 42 cases of nonaffective remitting psychoses as defined here.

Gender, Age, Race, and Duration of Untreated Psychosis

The female-to-male ratio was 1.7 (10:6) for nonaffective acute remitting psychosis and 0.7 (11:15) for other remitting psychoses. The average ages of the participants in the two groups were 36.1 years (SD=13.1) for those with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis and 31.7 years (SD=8.5) for those with other remitting psychoses. The majority of both groups were non-Hispanic white. Thirty-one percent of the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis and 19% of those with other remitting psychoses were from racial-ethnic minorities. None of the gender, age, or race differences were statistically significant.

The time from onset of psychosis to admission was shorter for the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis (mean=126 days, SD=465, median=3) than for the patients with other remitting psychoses (mean=841 days, SD=1030, median=365) (t=2.60, df=39, p<0.02; median test=13.82, df=1, p< 0.001). Therefore comparisons of course and outcome reported later were repeated after this variable was controlled.

Gender Differences in Age at Onset

Among those with other remitting psychoses, age at onset in male patients (mean=26.7, SD=8.5, median=25.0) was lower than in female patients (mean=31.7, SD=8.6, median=29.5). Although this difference is not statistically significant (t=1.44, df=23, p=0.16), its direction and magnitude are consistent with previous reports based on larger samples (10). Among cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis, however, the age at onset for male patients (mean=38.3, SD=16.7, median=36.5) was not lower than for female patients (mean=33.4, SD=11.1, median=30.0) (t=0.69, df=13, p=0.51).

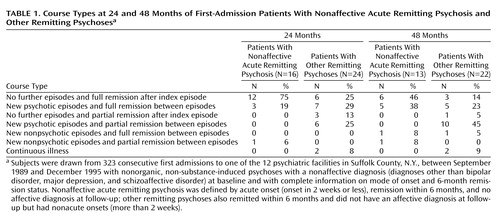

Course

At the 24-month follow-up, 75% of the cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis versus 25% of the cases of other remitting psychoses were in full remission, and the patients did not experience further episodes after the index episode (χ2=9.70, df=1, p=0.002; odds ratio=9.50, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.21–40.79, p=0.002) (Table 1). At 48-month follow-up, 46% of the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis versus 14% of the cases of other remitting psychoses could be thus classified (χ2=4.52, df=1, p=0.03; odds ratio=5.43, 95% CI=1.06–27.83, p=0.04). When time from onset to admission was entered into binary logistic regression models for predicting a course characterized by “no further episodes and full remission after index episode,” the odds ratios associated with psychosis group (nonaffective acute remitting psychosis versus other remitting psychoses) changed modestly to 10.39 (95% CI=2.05–52.53, p=0.005) for the 24-month follow-up and to 7.21 (95% CI=1.05–49.73, p=0.04) for the 48-month follow-up.

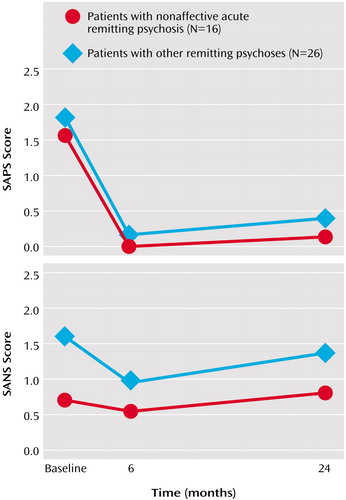

Symptom Severity

Generalized estimating equations analyses revealed a relatively large difference in the SANS scores between the nonaffective acute remitting psychosis group and the other remitting psychoses group (beta=–0.70, SE=0.21, p=0.001) (Figure 1). This effect persisted after time from onset to admission was controlled (beta=–0.79, SE=0.22, p<0.001). The difference for the SAPS was much smaller and not statistically significant (Figure 1).

Emotional Turmoil and Confusion

Four (25%) of the 16 patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis, compared with only one (4%) of the 26 patients with other remitting psychoses, presented with symptoms of emotional turmoil and confusion at baseline (χ2=4.23, df=1 p=0.04).

Treatment

Patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis received an average of 12.8 months (SD=9.7, median=13.5) of any treatment, including 12.4 months (SD=9.8, median=10.0) of antipsychotic medication treatment from intake to the 24-month follow-up, whereas patients with other remitting psychoses received an average of 16.5 months (SD=8.4, median=19.5) of any treatment, including 13.7 months (SD=9.2, median=15) of antipsychotic medication treatment in this period (any treatment: t=1.25, df=38, p=0.21; antipsychotic medication: t=0.84, df=36, p=0.41). During the 24- to 48-month period, patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis received an average of 12.0 months (SD=11.7, median=6.0) of any treatment, including 8.9 months (SD=11.8, median=0.0) of antipsychotic medication treatment, whereas patients with other remitting psychoses received an average of 16.1 months (SD=9.7, median=22.5) of any treatment, including 14.8 months (SD=10.0, median=19.0) of antipsychotic medication treatment (any treatment: t=1.13, df=33, p=0.27; antipsychotic medication: t=1.55, df=32, p=0.11).

Diagnosis

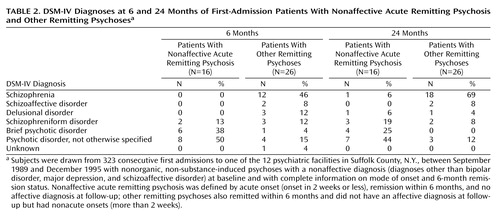

In the group with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis, 50% of the patients at 6-month follow-up and 44% at 24-month follow-up were assigned the DSM-IV residual diagnosis of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (Table 2). In contrast, only 15% of the patients with other remitting psychoses at 6 months and 12% at 24 months were assigned to this category (6 months: χ2=5.82, df=1, p=0.02; 24 months: χ2=5.67, df=1, p=0.02).

There were also significant differences in the proportions of patients with specific diagnoses across the two groups (Table 2). Among the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis, 50% (N=8) at the 6-month follow-up and 44% (N=7) at the 24-month follow-up met the DSM-IV criteria for brief psychotic disorder or schizophreniform disorder, whereas among the patients with other remitting psychoses, 15% (N=4) at the 6-month follow-up and 8% (N=2) at the 24-month follow-up received one of those diagnoses (6 months: χ2=5.82, df=1, p=0.02; 24 months: χ2=19.79, df=1, p=0.006). None of the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis at 6 months and only one patient (6%) at 24 months received a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, whereas 54% (N=14) of the patients with other remitting psychoses at 6 months and 77% (N=20) at 24 months received one of those diagnoses (6 months: χ2=12.92, df=1, p< 0.001; 24 months: χ2=19.79, df=1, p< 0.001).

The only notable change from 6 to 24 months in research diagnoses was the rise in the proportion of patients with other remitting psychoses who received a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: from 54% at the 6-month follow-up to 77% at the 24-month follow-up. Subsequent episodes among the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis did not always clarify the diagnosis. Of the three patients with recurrent psychotic episodes in the 24-month follow-up, all of whom had a 6-month diagnosis of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, two maintained this diagnosis at 24-month follow-up and one was given the diagnosis of brief psychotic disorder. The one patient who had nonpsychotic episodes with incomplete remission during the 24-month follow-up period received a diagnosis of schizophrenia at the 24-month point. The 6-month diagnosis of this patient was psychotic disorder not otherwise specified.

Discussion

In this cohort of first-admission patients with psychotic disorders, cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis were rare—only 5% of all first-admission nonaffective psychoses. This prevalence estimate is consistent with the 6% prevalence estimate reported earlier from other industrialized settings (10). Nevertheless, these psychoses appear to have a distinctive demographic, course, and symptom profile, justifying separate diagnostic classification.

This study had three main findings. First, nonaffective acute remitting psychosis was almost twice as common in female patients as in male patients, and there was no trend toward earlier age at onset in male patients, compared with female patients. By contrast, the comparison group of patients with other remitting psychoses exhibited the trends typically reported for schizophrenia: a slight male predominance and an earlier age at onset in male patients than in female patients. This finding is consistent with the results of our previous studies (10), as well as classic studies of acute remitting psychoses similar to nonaffective acute remitting psychosis (3). The reason for this distinctive gender distribution, however, remains unclear.

Second, nonaffective acute remitting psychosis had a distinctively benign course. Almost half of the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis remained in full remission throughout the 48-month period after the index episode. Furthermore, the large majority of the remaining cases who experienced further episodes recovered fully from these episodes. Only 6% of the patients at 24-month follow-up and 8% at 48-month follow-up were not fully recovered. By contrast, among the patients with other remitting psychoses, only 14% remained in full remission throughout the 48-month follow-up and, of those who had further episodes, the majority did not fully recover. These findings are consistent with other longitudinal studies from developing countries (13) as well as industrialized settings (15). The findings cannot be explained by time in treatment, since the patients with other remitting psychoses received more months of treatment than did the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis.

Third, the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis in our study had significantly lower negative symptom scores, compared to the patients with other remitting psychoses. This finding is not surprising, since the majority of the patients in the latter group received a diagnosis of schizophrenia, which is associated with more prominent negative symptoms. This finding underscores the difference between nonaffective acute remitting psychosis and schizophrenia suggested by our previous study (12). As noted earlier, patients with other remitting psychoses also had many of the other characteristics of schizophrenia, including earlier onset in male patients and a course characterized by recurrences and incomplete remission.

Despite their distinctive characteristics, a large proportion of the cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis could not be meaningfully classified by using the DSM-IV system. Half of the patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis at the 6-month follow-up and 44% at the 24-month follow-up received a diagnosis of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified—a residual category for cases that cannot be categorized in one of the specific DSM-IV diagnoses—because the duration of illness was longer than 1 month (hence disqualifying them for a diagnosis of brief psychotic disorder) or their symptoms did not conform to criterion A for schizophrenia (hence disqualifying them for a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder). Only 50% of the cases at 6 months and 44% at 24 months were given a diagnosis of brief psychotic disorder or schizophreniform disorder—DSM-IV diagnoses specifically designed for cases of remitting psychosis.

Although the introduction of the category of acute and transient psychotic disorders in ICD-10 was an advance toward incorporating these disorders in modern diagnostic systems, many cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis do not fit the criteria for acute and transient psychotic disorders, mostly because of the restrictive duration criteria for acute and transient psychotic disorders (1–3 months, depending on the specific disorder). Cases of acute remitting psychosis typically last longer than 1–3 months, with a modal duration of 2–4 months (14).

The low prevalence (25%) of symptoms of emotional turmoil and confusion among patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis in this study was unexpected. These features are commonly described as distinguishing features in the classic descriptions of acute remitting psychotic disorders. Therefore, we expected a higher prevalence of these symptoms in patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis. The failure to consistently identify characteristic symptoms supports the view (9) that it may be necessary to depart from the classic approach of defining these cases by relying on a specific constellation of symptoms and, instead, to base the diagnosis on mode of onset and time to remission.

The results of this study should be considered in the context of its limitations. First, in many of the cases of remitting psychoses, the remission might have been due to treatment with antipsychotic medication. To assess the effect of treatment on course, we conducted further analyses using multiple logistic regression in which psychosis group (nonaffective acute remitting psychosis versus other remitting psychoses) was the independent variable and being in full remission at 24 months was the dependent variable of interest. Comparing results of the logistic analysis with and without inclusion of the variable of medication status at the 6-month point did not reveal meaningful differences (effect of psychosis group before inclusion of 6-month medication status: odds ratio=10.00, 95% CI=2.34–42.78, p=0.002; after inclusion of 6-month medication status: odds ratio=11.12, 95% CI=2.36–52.35, p=0.002).

Second, some patients with nonaffective acute remitting psychosis with very brief duration may never seek treatment. Such potential cases would not be included in the Suffolk County Mental Health Project sample. As cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis are quite rare, large general population samples would be needed to reliably estimate the prevalence of such conditions.

In conclusion, in line with our previous work (10–14), these data support the view that nonaffective acute remitting psychosis is a highly distinctive condition. Yet, the current DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria do not adequately capture these cases, either because of restrictive duration criteria (for DSM-IV brief psychotic disorder and ICD-10 acute and transient psychotic disorders) or because of the requirement for the presence of schizophrenic symptoms (for DSM-IV schizophreniform disorder). Furthermore, since acute onset is not a criterion for the DSM-IV categories of schizophreniform disorder and brief psychotic disorder, cases of remitting psychosis with nonacute onset and typical cases of schizophrenia and other persistent psychoses in their early course are also included in these diagnostic groups along with the cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis. As the results of the present study show, there are significant differences between remitting psychoses with acute onset and those with nonacute onset.

The growing evidence from different settings may provide guidelines for revising the current diagnoses. The concept of acute and transient psychotic disorders in ICD-10, which draws on classic conceptions of acute remitting psychosis, is a suitable starting point. Extending the duration criterion of acute and transient psychotic disorders to 6 months would capture a large proportion of the cases of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis that are currently excluded because they have a duration longer than 1–3 months. Removing the current subclassification of acute and transient psychotic disorders, which is based on little evidence, would make the diagnosis easier to apply. We believe that incorporating such a revised diagnostic category in future editions of ICD and DSM would advance the study of nonaffective remitting psychoses and improve the applicability of these diagnostic systems in the developing countries, where these psychoses are much more common than they are in the industrialized world.

|

|

Received July 25, 2002; revision received March 27, 2003; accepted April 4, 2003. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York; and the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Mojtabai, 2600 Netherland Ave., Apt. 805, Bronx, NY 10463. Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-01754 (Dr. Mojtabai) and MH-44801 (Dr. Bromet) and by the Lieber Center for Schizophrenia Research (Dr. Mojtabai and Dr. Susser).

|

APPENDIX 1.

Figure 1. Severity of Positive and Negative Symptoms in Patients With Nonaffective Acute Remitting Psychosis and in Patients With Other Remitting Psychoses at Baseline and 6- and 24-Month Follow-Upa

aPositive symptoms measured with the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (23); negative symptoms measured with the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (24).

1. Kraepelin E: Psychiatry: A Textbook for Students and Physicians, 6th ed (1899). Translated by Metoui H. Canton, Mass, Watson Publishing International, 1990Google Scholar

2. Leonhard K: Cycloid psychoses: endogenous psychoses which are neither schizophrenic nor manic depressive. J Ment Sci 1961; 107:632–648Google Scholar

3. Perris C: A study of cycloid psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1974; 50(suppl 253):1–77Google Scholar

4. Magnan V, Legrain M: Les Dégénérés (État Mental et Syndromes Episodiques). Paris, France, Rueff, 1895Google Scholar

5. Pull CB, Pull MC, Pichot P: Nosologic position of schizoaffective psychoses in France. Psychiatr Clin 1983; 16:141–148Medline, Google Scholar

6. Astrup C, Fossum A, Holmboe R: A follow-up study of 270 patients with acute affective psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand Suppl 1959; 135:1–65Google Scholar

7. Langfeldt G: The Schizophreniform States. Copenhagen, Ejnar Munksgaard, 1939Google Scholar

8. Susser ES, Finnerty MT, Sohler N: Acute psychoses: a proposed diagnosis for ICD-11 and DSM-V. Psychiatr Q 1996; 67:165–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Menuck M, Legault S, Schmidt P, Remington G: The nosologic status of the remitting atypical psychoses. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 30:53–73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Susser ES; Wanderling J: Epidemiology of nonaffective acute remitting psychosis vs schizophrenia: sex and sociocultural setting. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:294–301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Susser ES, Varma VK, Malhotra S, Conover S, Amador XF: Delineation of acute and transient psychotic disorders in a developing country setting. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:216–219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Susser E, Fennig S, Jandorf L, Amador X, Bromet E: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and course of brief psychoses. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1743–1748Link, Google Scholar

13. Susser ES, Varma VK, Mattoo SK, Finnerty M, Mojtabai R, Tripathi BM, Misra AK, Wig NN: Long-term course of acute brief psychosis in a developing country setting. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173:226–230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Mojtabai R, Varma VK, Susser ES: Duration of remitting psychoses with acute onset: implications for ICD-10. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:576–580Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Pillman F, Haring A, Balzuweit S, Blöink R, Marneros A: The concordance of ICD-10 acute and transient psychosis and DSM-IV brief psychotic disorder. Psychol Med 2002; 32:525–533Medline, Google Scholar

16. Schwartz JE, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, Carlson G, Craig T, Galambos N, Lavelle J, Bromet EJ: Congruence of diagnoses 2 years after a first-admission diagnosis of psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:593–600Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Bromet EJ, Schwartz JE, Fennig S, Geller L, Jandorf L, Ksasznay B, Lavelle J, Miller A, Pato C, Ram R, Rich C: The epidemiology of psychosis: the Suffolk County Mental Health Project. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:243–255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, Anker M, Korten A, Cooper JE, Day R, Bertelsen A: Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures: a World Health Organization ten-country study. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl 1992; 20:1–97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Lieberman J, Jody D, Geisler S, Alvir J, Loebel A, Szymanski S, Woerner M, Borenstein M: Time course and biologic correlates of treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:369–376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Tohen M, Stoll AL, Strakowski SM, Faedda GL, Mayer PV, Goodwin DC, Kolbrener ML, Madigan AM: The McLean first-episode psychosis project: six-month recovery and recurrence outcome. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:273–281Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Gupta S, Andreasen NC, Arndt S, Flaum M, Hubbard WC, Ziebell S: The Iowa Longitudinal Study of Recent Onset Psychosis: one-year follow-up of first episode patients. Schizophr Res 1997; 23:1–13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Bromet EJ, Jandorf L, Fennig S, Lavelle J, Kovasznay B, Ram R, Tannenberg-Karant M, Craig T: The Suffolk County Mental Health Project: demographic, premorbid and clinical correlates of 6-month outcome. Psychol Med 1996; 26:953–962Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

24. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

25. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS: Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics 1988; 44:1049–1060Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar