Mental Disorders Among U.S. Military Personnel in the 1990s: Association With High Levels of Health Care Utilization and Early Military Attrition

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Epidemiological studies have shown that mental disorders are associated with reduced health-related quality of life, high levels of health care utilization, and work absenteeism. However, measurement of the burden of mental disorders by using population-based methods in large working populations, such as the U.S. military, has been limited. METHOD: Analysis of hospitalizations among all active-duty military personnel (16.4 million person-years) from 1990 to 1999 and ambulatory visits from 1996 to 1999 was conducted by using the Defense Medical Surveillance System. Rates of hospitalization, ambulatory visits, and attrition from military service were compared for persons with mental disorder diagnoses and those with diagnoses in 15 other ICD-9 disease categories. RESULTS: Mental disorders was the leading category of discharge diagnoses among men and the second leading category among women; 13% of all hospitalizations and 23% of all inpatient bed days were attributed to mental disorders. Six percent of the military population received ambulatory services for mental disorders annually in 1998 and 1999. Among a 1-year cohort of personnel, 47% of those hospitalized for the first time for a mental disorder left military service within 6 months. This attrition rate was significantly different from the rate of only 12% after hospitalization for any of the 15 other disease categories (range=11%–18%) (relative risk=4.04, 95% confidence interval=3.91–4.17). The difference remained significant after controlling for effects of age, gender, and duration of service. CONCLUSIONS: Mental disorders appear to represent the most important source of medical and occupational morbidity among active-duty U.S. military personnel. These findings provide new population-based evidence that mental disorders are common, disabling, and costly to society.

Epidemiological studies of mental disorders in the general population have found strong associations with reduced health-related quality of life, diminished productivity, absenteeism, unemployment, and high levels of health care utilization (1–9). The World Health Organization Global Burden of Disease study estimated that in 1990, 10% of all disability worldwide was attributable to neuropsychiatric disorders (10). Depression alone, a common, underrecognized, and treatable condition, has been predicted to become the second leading cause of worldwide morbidity over the next two decades (11, 12).

The U.S. military provides a unique opportunity to examine the burden of mental disorders in one of the healthiest segments of the U.S. population, an ethnically diverse population with equal access to comprehensive medical care. The 1.4 million service members on active duty in the U.S. military represent approximately 1% of the entire working adult population between the ages of 18 and 45 in the United States. We are not aware of any population-based studies to date addressing the rates of inpatient and ambulatory mental health care utilization across this important population. This is surprising, given the availability of one of the largest and most comprehensive integrated health utilization data systems. Data have been systematically collected on all hospitalizations among active-duty personnel since 1990 and on ambulatory visits since 1996. Electronic personnel records exist for the entire population, providing excellent demographic-specific denominator data. With very few exceptions (detailed later), active-duty personnel receive all of their inpatient medical care from military facilities, which provide services without cost to these individuals.

The objective of this study was to estimate the burden of mental disorders on the utilization of health care and on occupational functioning as measured by attrition from military service. We compared rates of hospitalization, hospital bed days, and outpatient visits related to mental disorder discharge diagnoses with those for 15 other major medical illness categories. Rates of hospitalization and ambulatory visits were examined over a 10-year (1990–1999) and a 4-year (1996–1999) period, respectively, across the entire military. We also examined the relationship of health care service use for mental disorders and career duration. Attrition rates (discharge from active-duty military service) after the first encounter for a mental disorder were compared with attrition rates after a first encounter for other medical illness categories. This study represents one of the largest published sources of population-based data on the impact of mental disorders on health care utilization and occupational functioning in a well-defined healthy working population.

Method

Surveillance Methods and Data Analysis

We conducted population-based analyses of hospitalizations occurring at U.S. military medical facilities between 1990 and 1999 among active-duty personnel from all four branches of service (Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines). The source of the data was the Defense Medical Surveillance System, which is an integrated database that includes demographic and health care utilization data for all military personnel who have been on active duty for at least 1 month. This information system is operated by the Army Medical Surveillance Activity, which routinely collects and analyzes medical surveillance data for policy makers and military health care providers (13). Defense Medical Surveillance System denominator data are obtained from the Defense Manpower Data Center (Monterey Bay, Calif.), which maintains up-to-date records on all personnel, including demographic data (age, gender, race) and service-related data (such as date of entry into service, date of separation from service, and occupation). These data are updated monthly, thus allowing longitudinal cross-sectional analyses.

Health care utilization data were obtained from all permanent U.S. military medical facilities worldwide. For all hospitalizations at military medical facilities, an electronic record, the Standard Inpatient Data Record, is generated at the time of discharge. These records include dates of admission and discharge, discharge diagnoses coded by using the ICD-9-CM, and personal identifiers that allow integration with the personnel (denominator) data files. Up to eight discharge diagnoses are recorded for each hospitalization. The Defense Medical Surveillance System receives updates of the Standard Inpatient Data Record records on a monthly basis. The accuracy of military inpatient electronic data has been shown to be comparable to that of other large health services information systems in the civilian sector (14, 15). One study demonstrated excellent agreement between the principal ICD-9 mental disorder diagnoses recorded in the electronic records and those determined by independent blinded psychiatric review of the hospital records (kappa=0.80–0.95) (15). While most inpatient care among active-duty service members is provided at military facilities, some hospitalizations occur at civilian facilities during emergencies or in remote locations where no military facility is available. However, admissions to civilian facilities, which are tracked by the military health system, accounted for less than 2% of all psychiatric hospitalizations among active-duty personnel in the 1990s and thus were not included in this analysis.

A new system for data on ambulatory care became available in 1996, but it took more than a year for all facilities to become automated. An estimated 60%–70% of facilities were reporting in 1997, and the most complete data were available for 1998 and 1999. Available ambulatory data include date of visit, ICD-9 diagnoses (up to four allowed), and personal identifiers. These records are electronically transmitted to the same facility that collects the inpatient data and are updated monthly and provided to the Defense Medical Surveillance System.

This is a descriptive study that used the entire active-duty military population as the denominator in calculating rates, with rates expressed as a function of total person-years of surveillance. Consequently, statistical tests of differences between population subgroups were used sparingly, both because the study included the entire population, rather than a sample, and because the enormous population size made virtually all comparisons statistically significant, whether or not they were clinically or epidemiologically important.

Classification of Disorders

The following categories of disorders were specified for comparison purposes by using ICD-9 codes (shown in parentheses): infectious and parasitic (001–139), neoplasms (140–239), endocrine/nutrition/metabolic/immunity (240–279), blood and blood-forming organs (280–289), mental disorders (290–319), nervous system and sense organs (320–389), circulatory (390–459), respiratory (460–519), digestive (520–579), genitourinary (580–629), complications of pregnancy/childbirth/puerperium (630–679), skin/subcutaneous tissue (680–709), musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (710–739), congenital (740–759), symptoms/signs/ill-defined conditions (780–799), and injury/poisoning (800–999). For most comparisons in this study the mental disorder category was compared with the 15 other ICD-9 illness categories.

The ICD-9 mental disorder category was further subdivided into eight broad diagnostic categories and additional subcategories, based on how the codes were used in DSM-IV. These eight categories were substance-related disorders, adjustment disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, psychotic disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform/dissociative disorders, and other mental disorders. The ICD-9 codes used to define each of these categories are shown in Table 1. Except for the codes for personality disorders and other mental disorders, only those ICD-9 codes that matched disorders listed in DSM-IV were included. The personality disorder category included only those ICD-9 codes included in DSM-IV plus two additional codes, 301.84 and 301.89, which were included in earlier versions of DSM and were subsumed under 301.9 (personality disorder not otherwise specified) in DSM-IV. The additional codes were included because the study spanned several years before and after the publication of DSM-IV. The “other mental disorder” category included a variety of DSM-IV codes (such as those for delirium, dementia), as well as all other codes within the ICD-9 mental disorder category that are not included in DSM-IV.

Attrition From Military Service

To determine the relationship between hospitalization for a mental disorder and subsequent attrition from military service, analysis was conducted on data for a cohort of all military personnel hospitalized for the first time in 1996. All individuals in this cohort were followed for 2 years or until the date they left active military service. Rates of attrition were computed for all major diagnostic categories on the basis of the date of first hospitalization in 1996. Attrition rates after the first recorded ambulatory service use in 1997 (the first year for which reasonably complete data were available) were also compared between groups. Statistical comparisons were made by using the chi-square test, with Mantel-Haenszel correction.

Results

Population Characteristics

Between 1990 and 1999, a total of 16,381,718 person-years of health surveillance were recorded among 4,815,864 active-duty military personnel. The median age of the population over the 10-year period was 26 years (minimum=17, maximum=65; 25th percentile=22, 75th percentile=34). Female personnel accounted for 12% of the population. The race/ethnic distribution was: white non-Hispanic 70.9%, African American non-Hispanic 18.9%, Hispanic 5.4%, Native American 0.8%, Asian 2.4%, and other 1.6%. There were no major demographic changes in the military in terms of age, gender, race/ethnicity, and educational level during the 10-year period.

Hospitalizations for Mental Disorder

Between 1990 and 1999, there were a total of 1,529,323 hospitalizations among active-duty personnel across the four services, of which 194,974 (13%) included a mental disorder diagnosis listed in any of the eight diagnosis fields (Table 2). Of these 194,974 hospitalizations, 109,451 (56%) were admissions to inpatient psychiatric wards, 31,883 (16%) were to inpatient alcohol/substance abuse rehabilitation units, and 53,640 (28%) were to other services (e.g., medical/surgical). A mental disorder was listed as the primary diagnosis for 161,038 (83%) of hospitalizations in which a mental disorder diagnosis was used.

The 109,451 psychiatric service hospitalizations occurred among 86,639 individuals (Table 2). The rate of hospitalization in an inpatient psychiatric service for these individuals over the 10-year period was 5.3 per 1,000 person-years, ranging from 6.6 in 1990 to 4.7 in 1999. The 31,883 total hospitalizations to alcohol/substance abuse rehabilitation services occurred among 30,530 individuals, for an incidence of 1.9 per 1,000 person-years overall for the 10-year period, ranging from 2.5 in 1990 to 0.2 in 1999. This decrease was due to closure of inpatient rehabilitation units and a shift of care to partial and intensive outpatient programs.

The 13% of hospitalizations involving primary mental disorder diagnoses accounted for 23% of all bed days. The median length of hospitalization was 6 days for patients with mental disorders compared with 2 days for patients with the other 15 categories of illness. In 1999 mental disorder diagnoses were utilized in 18% of all hospitalizations and were listed as the primary diagnosis in 15% of all hospitalizations. In 1999 hospital admissions listing a mental disorder as the primary discharge diagnosis resulted in 92,619 inpatient bed days (27%) of the total 337,387 bed days for all illness categories.

The most common primary mental disorder diagnoses over the 10-year period were alcohol- and substance-related disorders, adjustment disorders, mood disorders, and personality disorders (Table 1). Within the mood disorder category, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and dysthymia were most common.

Hospitalization Trends

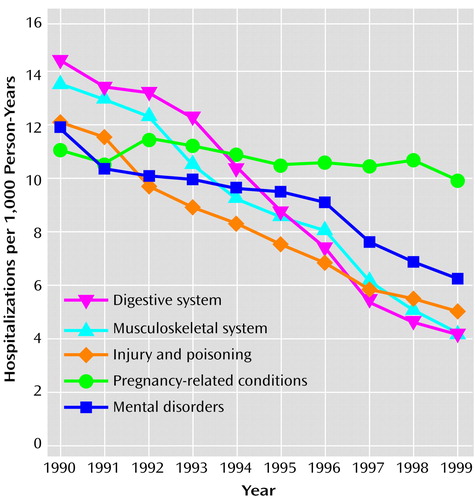

The rate of hospitalization for all illness categories among military personnel declined over the 10-year period, owing in part to new managed care initiatives phased in during the middle of the decade and to a shift to outpatient treatment for many services, such as same-day procedures. While mental disorder admissions also declined during this period, the rate of decline was much less than that for other illness categories. Of the 16 major ICD-9 categories, mental disorders were the fourth or fifth leading category between 1990 and 1993, behind musculoskeletal conditions, digestive system conditions, pregnancy-related admissions, and injuries (Figure 1). Mental disorders became the third leading cause of hospitalization in 1994 and the second leading cause of hospitalization since 1995. The rate of pregnancy-related hospitalizations, which included normal deliveries, remained stable during the 10-year period.

Demographic Characteristics

Table 3 shows rates of first hospitalization and demographic correlates for all mental disorder diagnoses from 1990 to 1999. Higher rates of hospitalization for mental disorders occurred among those of younger age, female gender, and single marital status. With regard to race or ethnicity, rates of these diagnoses were similar among blacks, Hispanics, and whites, slightly lower for Asian/Pacific Islanders, and higher for American Indian/Alaskan Natives.

Outpatient Clinic Visits

In 1998–1999, 11,275,733 ambulatory care visits for all ICD-9 diagnoses (excluding V codes) were reported (Table 4). Mental disorders were listed as the primary diagnosis for 9% of these visits, representing the fifth leading diagnostic category among ambulatory care visits. In 1998–1999, 172,304 service members were treated for a mental disorder, giving an incidence rate of 63 per 1,000 person-years. The distribution of diagnoses is shown in Table 1.

Association of Mental Disorders With Military Attrition

Service members who were hospitalized for mental disorders left military service at a significantly higher rate than those hospitalized for any of the 15 other ICD-9 illness categories (Table 5). For example, within 6 months after hospitalization, 47% of soldiers hospitalized for the first time in 1996 with a mental disorder as a primary diagnosis left military service. In contrast, only 12% (range=11%–18%) of those hospitalized for the first time for other medical illnesses left service within 6 months (relative risk=4.04, 95% confidence interval [CI]=3.91–4.17, χ2=6,647, df=1, p<0.0001). This striking association remained significant after controlling for the effects of age, gender, and length of military service. Ambulatory care for mental disorders was similarly highly correlated with military attrition. Of the 65,562 military personnel who were reported to have received a diagnosis of a mental disorder for the first time as an outpatient in 1997, 17,431 (27%) left active duty within 6 months of their first visit, compared with only 76,162 (9%) of 857,490 individuals after an initial ambulatory visit for any of the other 15 illness categories (range=6%–19%) (relative risk=2.99, 95% CI=2.95–3.04, χ2=20.95, df=1, p<0.0001). These marked differences remained highly significant after controlling for the effects of age, gender, or length of service.

Discussion

This work represents one of the largest studies that directly compared rates of health care utilization for mental disorders with other disease categories in a large, predominantly young adult working population with equal access to medical care. The U.S. military represents approximately 1% of the entire U.S. adult working population between the ages of 18 and 45 (∼0.5% of women and 2% of men in this age group). Our analyses confirm that mental disorders are a major public health problem and a leading cause of occupational dysfunction in this population. Mental disorder diagnoses were involved in 13% of all hospitalizations, and these hospitalizations accounted for nearly a quarter of all inpatient bed days among active-duty military personnel. For the last 5 years of the study, mental disorders were the second leading hospital discharge diagnostic category. Alcohol and substance use disorders, adjustment disorders, mood disorders, and personality disorders were the most common diagnoses. More than 6% of the entire active-duty population was reported to have received outpatient treatment for a mental disorder annually in 1998 and 1999.

The fact that mental disorders shifted to become the second leading ICD-9 discharge diagnostic category during the 1990s suggests that these disorders were relatively resistant to managed care strategies compared with other illness categories. However, additional factors may have influenced health care utilization trends for mental disorders in the military, including stresses of military life, efforts to destigmatize treatment for mental illness, and improved case-finding and diagnosis. In addition, secular trends in rates of mental disorders among adolescents (16–18) may have counterbalanced managed care measures in this predominantly young adult population. Although younger age and female gender were associated with higher rates of mental disorder hospitalizations in this study, there was no evidence of major demographic changes in the military over the study period that could account for the observed trends.

In what way does this study add to the existing literature, and how generalizable are these data to civilian populations? We are not aware of any other studies that offer such comprehensive population-based mental health care utilization data, especially for a young adult working segment of the population. All studies of mental health care utilization to date have derived estimates by very different methods, such as through surveys of hospitals (19–23), community-based surveys such as the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study and the National Comorbidity Survey (24–30), and data from insurance organizations (31, 32). An advantage of our study is that it avoids many potential methodological problems of studies in civilian populations, such as reliance on U.S. census data for denominators, difficulties in clearly defining catchment areas of health care facilities, inequalities in health care coverage or access to medical services, and limitations inherent in any survey design, such as sampling errors, respondent errors, and nonrandom refusals (27, 33, 34).

Perhaps most comparable with the data in this study are data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey, which involved a sample of hospitals with average lengths of stay of less than 30 days and utilized census data for denominators (19–21). For example, in 1996, the rate of hospital discharge for mental disorders (as a primary diagnosis) among persons 15–44 years of age was estimated to be 9.7 per 1,000 persons (19). This estimate was remarkably similar to the overall annual rate that we measured of 9.8 per 1,000 active-duty personnel, providing strong support for the generalizability of the data from this large military population.

While this is encouraging, more research is clearly needed to refine these comparisons and take into account the complexities of the different health care systems. For example, clinicians in civilian settings may not be reimbursed for treating patients with adjustment disorders, one of the most common diagnostic categories in military populations. There is evidence that factors unique to the military environment, such as limitations in confidentiality and methods of referral, may influence psychiatric diagnostic practices (35, 36). Although there is no standardized screening instrument for psychiatric disorders used routinely at the time of accession into the military, service members undergo a comprehensive medical evaluation and are unlikely to be accepted into service if they report any significant psychiatric history. This may have an effect on reducing utilization, which would in turn make the estimates of disease burden derived from this study more conservative. Although these examples can be viewed as limitations of this study, they also suggest the opportunity for enormous potential benefits to the military and society of systematic epidemiologic research to further characterize the factors that predict high levels of mental health care utilization. The availability of integrated population-based data systems in the military represents an unprecedented opportunity to define these risk factors while avoiding many of the problems of health services research in civilian populations.

One strength of our study was the opportunity to define utilization patterns in a well-characterized population in which all members have equal access to “free” medical care (33). One might predict that differences in utilization seen in other studies, such as disparate rates by race/ethnic groups, would not be as apparent in an employed population with equal access to medical services, which is indeed what we found among Caucasians, Hispanics, and African Americans.

Particularly striking was the magnitude of the apparent occupational impact of mental disorders compared with other medical conditions, as measured by attrition from military service. Nearly 50% of personnel hospitalized for the first time for a mental disorder left military service within 6 months, compared with only 12% of those hospitalized for other reasons. This difference was independent of age, gender, or duration of service. Even ambulatory care use for mental disorders was associated with a higher rate of attrition, compared with ambulatory service use for other disease categories.

The reasons for the strong association between health care utilization for mental disorders and subsequent attrition require further study. Our findings raise a number of questions regarding the comparability of military attrition and civilian job loss, and the degree to which military occupational functioning predicts occupational dysfunction in other settings. Clearly, the pathways involving job application, employment, voluntary or involuntary job loss, and disability in association with health care treatment are complex for both military and civilian organizations. One of the limitations of this study is that the data system we used does not provide accurate information about the reasons people left military service. However, it is likely that mental disorders not only contributed to higher rates of medical discharges but to other types of discharges, such as those related to legal, conduct, and behavioral problems and to failure to meet minimum performance requirements. Less likely is an inflation of service utilization due to an incentive to be discharged from service for disability benefits. Many of the mental disorders likely to be diagnosed among service members, including adjustment disorders, personality disorders, and alcohol/substance abuse, are not compensable conditions in military and Veterans Administration disability systems. Disability determinations for other axis I disorders, such as mood disorders and anxiety disorders, depend on many factors in addition to the medical assessment, including the degree of occupational impairment and length of time in military service. Regarding psychotropic medication use, there is no uniform policy prohibiting the use of these medications while on active duty; they are used routinely (especially antidepressants), and such use is not grounds for separation.

The U.S. military remains one of the most highly respected and effective military organizations in the world, and these medical data do not suggest that the impact of mental disorders is greater among service members than in the general U.S. population. Nevertheless, these data speak to the pervasive nature of mental disorders even in the healthiest segment of the population. The impressive difference in attrition rates and the fact that this difference was consistent across inpatient and outpatient services suggest that mental disorders may have a greater adverse influence on occupational functioning than any other medical illness category.

|

|

|

|

|

Presented in part at the American Psychiatric Association Institute on Psychiatric Services, Orlando, Fla., Oct. 10–14, 2001. Received June 22, 2001; revision received Dec. 5, 2001; accepted April 15, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry and the Deployment Health Clinical Center, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C.; the Division of Neuropsychiatry, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Medical Research and Materiel Command; Army Medical Surveillance Activity, U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine, Washington, D.C.; the Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md.; and the Health Policy and Services Directorate, Headquarters, U.S. Army Medical Command, Fort Sam Houston, Tex. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hoge, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Division of Neuropsychiatry, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, 503 Robert Grant Ave., Silver Spring, Md., 20910; [email protected] (e-mail). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, the U.S. Government, or any of the institutional affiliations listed.

Figure 1. Rate of Hospitalization for the Five Leading Primary ICD-9 Diagnostic Categories Among All Active-Duty Military Personnel, 1990–1999a

aSame-day episodes excluded. Pregnancy-related conditions included normal deliveries.

1. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:914-919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:11-19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wells KB, Sherbourne CD: Functioning and utility for current health of patients with depression or chronic medical conditions in managed, primary care practices. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:897-904Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK: Depression, disability days and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 1990; 264:2524-2528Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 1992; 267:1478-1483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W: Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:352-357Link, Google Scholar

7. Kessler RC, Frank RG: The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychol Med 1997; 27:861-873Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Klerman GL, Weissman MM: The course, morbidity, and costs of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:831-834Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Johnson J, Greenwald S: Panic attacks in the community: social morbidity and health care utilization. JAMA 1991; 265:742-746Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Murray CJL, Lopez AD (eds): Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

11. Murray CJL, Lopez AD: Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997; 349:1498-1504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

13. Brundage JF, Kohlhase KF, Rubertone MV: Hospitalizations for all causes of US military service members in relation to participation in Operations Joint Endeavor and Joint Guard, Bosnia-Herzegovina, January 1995 to December 1997. Milit Med 2000; 165:505-511Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Meyer GS, Krakauer H: Validity of Department of Defense standard inpatient data record for quality management and health services research. Milit Med 1998; 163:7:461-465Google Scholar

15. Dlugosz LJ, Hocter WJ, Kaiser KS, Knoke JD, Heller JM, Hamid NA, Reed RJ, Kendler KS, Gray GC: Risk factors for mental disorder hospitalization after the Persian Gulf War: US Armed Forces, June 1, 1991-September 30, 1993. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52:1267-1278Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Fombonne E: Increased rates of depression: update of epidemiological findings and analytical problems. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:145-156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Achenbach TM, Howell CT: Are American children’s problems getting worse? a 13-year comparison. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 6:1145-1154Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Iyengar S, Orvaschel H, Reich T, Dahl RE, Puig-Antich J: A secular increase in child and adolescent onset affective disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:600-605Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Graves EJ, Kozak LJ: National hospital discharge survey: annual summary, 1996. Vital Health Stat 1999; 13(140):i-iv, 1-46Google Scholar

20. Mechanic D, McAlpine DD, Olfson M: Changing patterns of psychiatric inpatient care in the United States, 1988-1994. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:785-791Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Olfson M, Mechanic D: Mental disorders in public, private nonprofit, and proprietary general hospitals. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1613-1619Link, Google Scholar

22. Health, United States, 1999. DHHS Publication 99-1232. Hyattsville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

23. Goldsmith HF, Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ, Sacks AJ: Projections of inpatient admissions to specialty mental health organizations: 1990-2010. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:478-483Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:85-94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Narrow WE, Regier DA, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ: Use of services by persons with mental and addictive disorders: findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:95-107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Shapiro S, Skinner EA, Kessler LG, VonKorff M, German PS, Tischler GL, Leaf PJ, Benham L, Cottler L, Regier DA: Utilization of health and mental health services: three Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:971-978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Regier DA, Kaelber CT: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) program: studying the prevalence and incidence of psychopathology, in Textbook of Psychiatric Epidemiology. Edited by Tsuang MT, Tohen M, Zahner GEP. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1995, pp 135-155Google Scholar

28. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8-19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Kessler RC, Frank RG, Edlund M, Katz SJ, Lin E, Leaf P: Differences in the use of psychiatric outpatient services between the United States and Ontario. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:551-557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Gallo J, Cai G, Tien A, Romanoski A, Lyketsos C, Chen LS: Natural history of Diagnostic Interview Schedule/DSM-IV major depression: the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:993-999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Leslie DL, Rosenheck R: Shifting to outpatient care? mental health care use and cost under private insurance. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1250-1257Abstract, Google Scholar

32. Leslie DL, Rosenheck R: Changes in inpatient mental health utilization and costs in a privately insured population, 1993-1995. Med Care 1999; 37:457-468Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1775-1777Link, Google Scholar

34. Eaton WW, Holzer CE III, VonKorff M, Anthony JC, Helzer JE, George L, Burnam A, Boyd JH, Kessler LG, Locke BZ: The design of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys: the control and measurement of error. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:942-948Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. McCarroll JE, Orman DT, Lundy AC: Clients, problems, and diagnoses in a military community mental health clinic: a 20-month study. Milit Med 1993; 158:701-705Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. McCarroll JE, Orman DT, Lundy AC: Differences in self- and supervisor-referrals to a military mental health clinic. Milit Med 1993; 158:705-708Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar