Brain-to-Serum Lithium Ratio and Age: An In Vivo Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to determine if there is an association between brain-to-serum lithium ratios and age. METHOD: Lithium-7 magnetic resonance spectroscopy was used to measure in vivo brain lithium levels in nine children and adolescents (mean age=13.4 years, SD=3.6) and 18 adults (mean age=37.3, SD=9.1) with bipolar disorder. RESULTS: Serum and brain lithium concentrations were positively correlated. Younger subjects had lower brain-to-serum concentration ratios than adults: 0.58 (SD=0.24) versus 0.92 (SD=0.36). The brain-to-serum concentration ratio correlated positively with age. CONCLUSIONS: These observations suggest that children and adolescents may need higher maintenance serum lithium concentrations than adults to ensure that brain lithium concentrations reach therapeutic levels.

Since children have a higher glomerular filtration rate than adults and lithium is eliminated by a renal route (1), children and adolescents receiving lithium treatment require larger doses of lithium in relation to their weight than adults to achieve therapeutic serum lithium levels (2). However, it is known that serum lithium levels are not always accurate in predicting therapeutic response or adverse effects (3).

Few studies have looked at lithium pharmacokinetics in children and adolescents (4). Use of lithium-7 (7Li) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) makes it possible to measure in vivo lithium brain levels (5). 7Li MRS results have shown correlations (r2) of 0.50 to 0.97 between brain and serum lithium levels (1, 5–7). Studies have suggested that brain lithium levels may provide a better measure of lithium efficacy than serum lithium levels (5). The purpose of the current study was to investigate the relationship between age and lithium levels in the brain and/or serum.

Method

Nine children and adolescents and 18 adults who were actively receiving lithium medication participated in this study. The mean age of the children was 13.4 years (SD=3.6); five were boys, and four were girls. All were interviewed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Epidemiologic Version (8). All had a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. Additional diagnoses were attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (N=4), attention deficit disorder (N=2), oppositional defiant disorder (N=2), obsessive-compulsive disorder (N=1), and social adjustment disorder (N=1).

Inclusion criteria for the children were an age range of 7–18 years and active treatment with lithium for at least 30 days with a current stable dose. Exclusion criteria were a history of drug or alcohol abuse within 4 months of study entry, a history of seizures or organic brain disorder, mental retardation (IQ<80), inability to comply with instructions or procedures of the study, and presence of metal pins or braces. The parents of children who were potential subjects for the study were capable of understanding the nature of this study as well as the discomforts and potential benefits, which were explained in full. The parents of all children included in the study provided written informed consent.

The mean age of the 19 adults who participated in the study was 37.3 (SD=9.10); 10 were men, and eight were women. All had a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar I or bipolar II disorder as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version. Exclusion criteria for the adults were substance abuse in the month before participating in the study, obsessive-compulsive disorder, pregnancy, or unstable medical illness. After a complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. This study has been approved by the institutional review board of McLean Hospital.

Serum and brain lithium levels were acquired 10–12 hours after the last dose of lithium. All MRS examinations were performed on a General Electric 1.5-T Signa advantage scanner (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee) with a double-tuned head coil (proton [1H] and 7Li: U.S. Asia Instruments, Highland Heights, Ohio). The same method is applied in all studies from our department and has been described in detail by González et al. (6). Morphometric images were acquired with the 1H channel, and the 7Li spectra were acquired with the 7Li channel. 7Li spectra were acquired from a 60-mm axial slice centered on the superior edge of the ventricles. Serum lithium levels were acquired before the MRS examination, 12 hours after the last dose of lithium. The spectra were fit by using SA/GE (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee), and the images were segmented to determine the percent contributions to the lithium signal from the brain, CSF, and muscle by using CINE software (9). Finally, brain lithium concentrations were calculated according to the method of González et al. (6).

Statistical analysis was performed with analysis of variance and regression analysis; significance was set at p<0.05. Younger subjects were all subjects with an age of 18 years or less; older subjects were all subjects older than 18.

Results

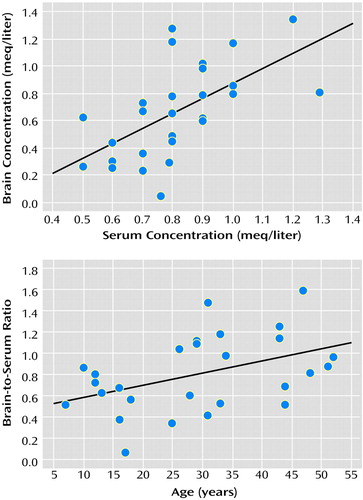

There was a positive correlation between serum and brain lithium concentrations (r=0.60, N=27, p<0.001) (Figure 1). Brain-to-serum lithium concentration ratios were lower in younger subjects (mean=0.58, SD=0.24) than adults (mean=0.92, SD=0.36) (F=6.75, df=1, 25, p<0.02). In addition, the brain-to-serum concentration ratio correlated positively with age (r=0.44, N=27, p<0.02) (Figure 1).

There was no significant difference between serum lithium levels in younger (mean=0.87 meq/liter, SD=0.21) and older (mean=0.78 meq/liter, SD=0.18) subjects (F=1.34, df=1, 25, p=0.26) or between brain lithium concentrations in younger (mean=0.52 meq/liter, SD=0.27) and older (mean=0.74 meq/liter, SD=0.36) subjects (F=2.73, df=1, 25, p=0.11). There was no significant correlation between serum lithium concentrations and age (r=0.22, N=27, p<0.27) or between brain lithium concentrations and age (r=0.26, N=27, p<0.18).

Discussion

The brain-to-serum lithium ratio increased with age in the absence of a relationship between serum lithium levels and age or brain lithium levels and age. There are limitations to this study; specifically, the number of patients was small and the findings are preliminary.

It has been suggested (10) that brain cells actively extrude lithium, probably through the sodium-lithium counter-transport system. Several studies (10–12) have shown that red blood cells, neurons, and glia actively export lithium from intracellular to extracellular space. Therefore, the results seen in this study most likely show that children and adolescents extrude lithium more effectively from their brain cells than adults do. This may suggest that children and adolescents should be maintained at higher serum lithium concentrations than adults to ensure that brain lithium concentrations reach therapeutic levels.

Received Feb. 29, 2000; revision received Dec. 26, 2001; accepted Feb. 19, 2002. From the Consolidated Department of Psychiatry, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass. Address reprint requests to Dr. Constance Moore, Brain Imaging Center, McLean Hospital, 115 Mill St., Belmont, MA 02478; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the National Association for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression (Dr. C.M. Moore), by NIMH grants MH-01978 (Dr. C.M. Moore) and MH-58681 (Dr. Renshaw), and by the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Disorders Research Center at McLean Hospital.

Figure 1. Brain and Serum Lithium Concentrations and Relation of Brain-to-Serum Lithium Ratio to Age for 27 Patients With Bipolar Disorder Who Were 7–52 Years Olda

aThere were significant correlations between brain and serum lithium levels (r=0.60, N=27, p<0.001) and between brain-to-serum lithium ratio and age (r=0.44, N=27, p<0.02).

1. Kilts CD: In vivo imaging of the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of lithium. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 9):41-46Google Scholar

2. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Official action: summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:1580-1582Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kilts CD: The ups and downs of oral lithium dosing. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 6):21-26Google Scholar

4. Vitiello B, Behar D, Malone R, Delaney MA, Ryan PJ, Simpson GM: Pharmacokinetics of lithium carbonate in children. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1988; 8:355-359Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Komoroski RA: Applications of (7)Li NMR in biomedicine. Magn Reson Imaging 2000; 18:103-116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. González RG, Guimaraes AR, Sachs GS, Rosenbaum JF, Garwood M, Renshaw PF: Measurement of human brain lithium in vivo by MR spectroscopy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1993; 14:1027-1037Medline, Google Scholar

7. Plenge P, Stensgaard A, Jensen HV, Thomsen C, Mellerup ET, Henriksen O: 24-Hour lithium concentration in human brain studied by Li-7 magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:511-516Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Puig-Antich J, Orvaschel H, Tabrizi M, Chambers WJ: The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E), 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Yale University School of Medicine, 1980Google Scholar

9. Johnson LA, Pearlman JD, Miller CA, Young TI, Thulborn KR: MR quantification of cerebral ventricular volume using a semiautomated algorithm. AJNR: Am J Neuroradiol 1993; 14:1373-1378Medline, Google Scholar

10. West IC, Rutherford PA, Thomas TH: Sodium-lithium countertransport: physiology and function. J Hypertens 1998; 16:3-13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Mallinger AG, Hanin I, Himmelhoch JM, Thase ME, Knopf S: Stimulation of cell membrane sodium transport activity by lithium: possible relationship to therapeutic action. Psychiatry Res 1987; 22:49-59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Mallinger AG, Frank E, Thase ME, Dippold CS, Kupfer DJ: Low rate of membrane lithium transport during treatment correlates with outcome of maintenance pharmacotherapy in bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 1997; 16:325-332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar