Smoking and Depression: An Examination of Mechanisms of Comorbidity

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Although the association between depression and smoking has been consistently established, little evidence regarding the mechanisms that influence this association is currently available. The present study evaluates alternate familial mechanisms of comorbidity between depression and smoking. METHOD: Probands from a case-control family study were selected from outpatient specialty clinics or through a random-digit dialing procedure. A total of 133 probands and 273 directly interviewed, first-degree relatives of the probands were included in the present analyses. RESULTS: The pattern of cross-aggregation of heavy smoking and depression differed according to the subtype of depressive disorder. There was evidence of a shared etiology between dysthymia and heavy smoking, whereas major and double depression did not demonstrate a shared vulnerability with heavy smoking. CONCLUSIONS: This report contributes to the present sparse evidence regarding the mechanisms involved in the etiology of smoking and depressive disorders and highlights the need for greater attention to this issue through genetic epidemiological study methods.

Numerous epidemiological studies have shown substance use to be strongly associated with depression in adolescent (1, 2) and adult (3, 4) samples. Furthermore, both twin and family investigations have been undertaken to test alternative conceptual models for this association. Evidence regarding the mechanism of comorbidity between alcoholism and major depression has recently emerged to support a causal relationship for the alternative hypothesis that the two conditions share a common etiology (for a review, see reference 5). However, evidence related to individual classes of drug use has been sparse.

An examination of comorbidity between smoking and depression has yielded similarly strong estimates of association (6–10); however, little evidence regarding the mechanisms that influence the association is currently available. A causal relationship has been suggested, such that depression may result from neurochemical changes brought on by smoking, or that depression may cause smoking by increasing the likelihood that individuals will self-medicate negative feelings with nicotine (11–14). Alternatively, the association between the two conditions may result from shared genetic or environmental factors that independently increase the risk of having both conditions (6, 8). One study of female twins provided evidence for the latter alternative. Specifically, Kendler and colleagues (15) found higher rates of smoking and major depression in the co-twins of monozygotic probands than in the co-twins of dizygotic probands with major depression, suggesting that the relationship between smoking and major depression may result from genetic factors that predispose individuals to both conditions. To date, additional twin or family study data have not addressed this question.

Comorbidity research examining specific levels of smoking has indicated that depression is most strongly associated with heavy smoking and nicotine dependence rather than with lower levels of use (15–17). In contrast, an examination of increasing levels of depressive symptoms and/or subtypes of depressive disorders has not been pursued, to our knowledge. With few exceptions (18), epidemiologic studies that have reported the association between depression and smoking have exclusively inspected the category of major depression rather than other depressive subtypes.

The present study employs family study data to discriminate between causal and shared etiologic mechanisms for the co-occurrence of smoking and depression. Alternate explanations for associations between smoking and depression are tested by examining patterns of expression of comorbid and noncomorbid conditions among the relatives of probands with comorbid and noncomorbid conditions (19). If the relationship between smoking and depression is causal, we expect to see the specificity of transmission within families, such that relatives of probands with depression show a higher rate of smoking but only in the presence of comorbid depression. Alternatively, if each condition shares common risk factors (either genetic or environmental), relatives of probands with either disorder should have higher rates of the other disorder than normal comparison subjects.

Method

Study Group

A total of 260 probands were selected from both outpatient substance abuse and outpatient anxiety clinics at the Connecticut Mental Health Center (New Haven, Conn.) or through a random-digit dialing procedure in the greater New Haven area. All of the normal comparison subjects, 18% of the probands with substance abuse (representing marijuana or sedative abuse and/or alcoholism), and 47% of the probands with anxiety disorders were recruited from the community. The rates of major depression and dysthymia were statistically similar in each treatment and community-ascertained psychiatric group. Information was also obtained for 1,239 first-degree relatives and 292 spouses of the probands. Data for 133 probands and 273 directly interviewed, first-degree relatives for whom information on tobacco use was collected were used for the present analyses. The effects of ascertainment source were included in all of the analyses.

Interview Procedures

All procedures complied with strict ethical standards in the treatment of human subjects and were approved by the Yale University School of Medicine’s institutional review board. Care was taken in the written informed consent process to ensure that all participants were knowledgeable about the study and willing to participate. Once written consent was obtained from the probands, they were directly interviewed with a structured interview about health, behavior, and psychiatric and substance use disorders, and a pedigree was generated that identified spouses/ex-spouses with whom probands had children and all first-degree biological relatives. Independent interviewers, blind to the identity of and information on the proband, directly interviewed the spouses and first-degree relatives of the probands, either by telephone or in person. A total of 57% of the eligible first-degree relatives and spouses were interviewed directly (20).

The diagnostic interview for the probands and their relatives was a modified version of the DSM-III-R semistructured Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, current and lifetime versions (21). The probands and interviewed first-degree relatives provided family history data for all their first-degree relatives by means of a version of the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria developed by Andreasen and colleagues for data collected by the family history method and adapted to DSM-III and DSM-III-R criteria (22). The final diagnoses were best estimates based on all available information, including the diagnostic interview, family history reports of each proband and relative, and medical records. Best estimates were performed by psychiatrists with expertise in substance use and anxiety disorders who were blind to the diagnostic status of the probands and relatives. Each case was reviewed by at least two diagnosticians.

The tobacco section of the diagnostic interview included questions on age at onset of cigarette use, as well as the frequency and quantity of daily smoking. Lifetime smoking history was characterized according to the presence of heavy regular use (i.e., more than one pack of cigarettes or 20 or more cigarettes per day).

Statistical Methods

Logistic regression analyses were conducted, as well as standard chi-square tests for the associated contingency tables (SAS, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.). The co-aggregation of smoking and depressive disorders was examined by the inclusion of these conditions in the probands and relatives, as well as adjustment for the effects of proband ascertainment source, sex, and psychiatric and substance use disorder comorbidity in the probands and relatives. Although case-control sampling was used to select the probands in this study, the relatives were a historical cohort group. The relatives were stratified by exposure type (proband group) and then followed from birth until disease onset (before the interview date) to assess the onset of disorders by means of recall. We chose to assign a dichotomous measure of disorder status (i.e., yes/no) rather than age at onset. For adults, recalling ages for levels of tobacco use or ages at onset for depressive disorders may be problematic. Furthermore, most relatives had aged beyond the period of risk for onset of the outcomes of interest. Because the data were prospective in nature, relative risk was the appropriate measure of association between exposure and disease. Since the outcomes in our study group were not rare events, the odds ratio was not a good estimator of the population’s relative risk. Thus, instead of using a logistic regression model, we used a relative-risk regression model (23) to estimate risk ratios and their standard errors in our analyses (GLIM, Numerical Algorithms Group, Ltd., Oxford, U.K.). This model for binary outcomes uses a log link function and restricts the parameter space to keep predicted values within the 0–1 range. Estimates and confidence intervals are presented. Analysis of variance was used to examine continuously defined variables with SAS. All analyses were two-tailed.

Results

Proband Characteristics

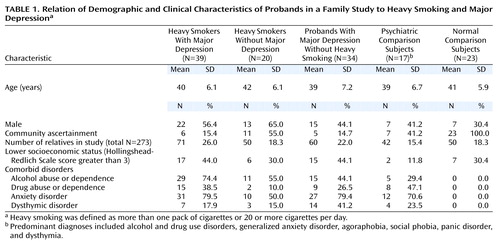

Mutually exclusive proband groups were created on the basis of the presence of heavy regular smoking and major depression. These groups included those with comorbid major depression and heavy smoking, major depression without heavy smoking, and heavy smoking without major depression; there were also groups of psychiatric comparison subjects (their predominant diagnoses included alcohol and drug use disorders, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, panic disorder, and dysthymia) and normal comparison subjects. The demographic and psychiatric disorders that were the basis of selection are presented in Table 1. The probands were between the ages of 25 and 56 (mean age=40 years, SD=6). A total of 53% (N=70) of the probands were female, and 47% (N=63) were male. Alcohol abuse or dependence was more prevalent among probands with both major depression and heavy smoking than among probands with only one of these conditions or among psychiatric comparison subjects (χ2=13.82, df=3, p<0.004). The rates of drug abuse or dependence, dysthymia, and anxiety disorders were similar across groups, with the exception of the normal comparison subjects. Proband groups were also similar in terms of age, sex, and socioeconomic status on the basis of chi-square tests.

Comorbidity Among Relatives

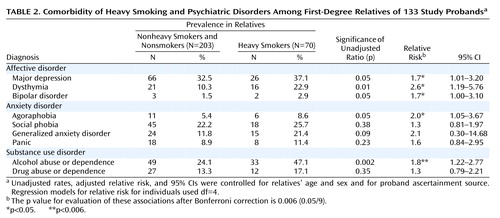

The interviewed relatives included 177 (65%) women and 96 (35%) men. The mean age was 42.7 years (SD=17.0, range=18–80). A total of 26% (N=70) of the relatives had a lifetime history of heavy smoking. Heavy smokers were older (mean=46 years, SD=15, versus mean=41 years, SD=18) (F=4.56, df=1, 272, p<0.04) and more likely to be male (50% men versus 30% men) (χ2=9.09, df=1, p<0.003) than the nonheavy smokers and nonsmokers. To establish the magnitude of association between heavy smoking and psychiatric disorders among the relatives of probands, bivariate associations were examined (Table 2). Bonferroni adjustment of the p value for evaluating these associations resulted in a p value of 0.05/9=0.006. After adjustment for the relatives’ age and sex and the ascertainment source of the proband, only alcohol use disorders were significantly associated with heavy smoking. Additionally, major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, and agoraphobia were marginally associated with heavy smoking among the relatives, meeting the p<0.05 confidence level.

Psychiatric Disorders Among Relatives

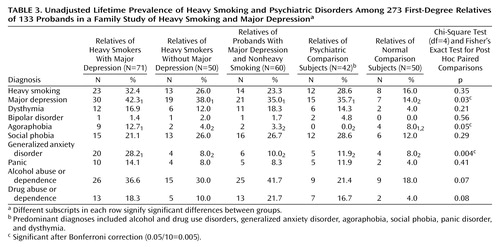

The rates of smoking and psychiatric disorders in the relatives from each proband group are presented in Table 3. Bonferroni adjustment of the p value for evaluating the corresponding chi-square tests resulted in a p value of 0.05/10=0.005. The rates of major depression were found to be marginally higher among the relatives of each smoking and/or psychiatric proband group than among the relatives of the normal comparison subjects. The rates of generalized anxiety disorder were higher among the relatives of probands with both heavy smoking and major depression than among the relatives of each of the remaining proband groups.

Multivariate Modeling

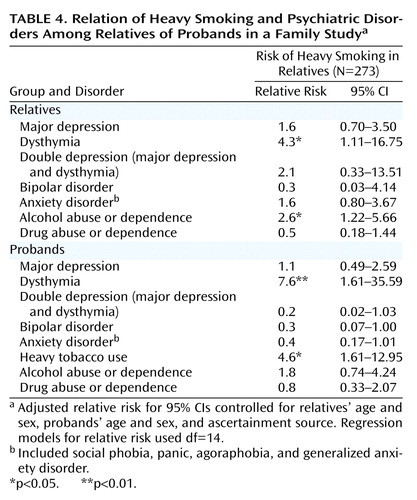

The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis simultaneously examining comorbidity and cross-aggregation of depression and heavy smoking with the inclusion of alternate disorders in the probands and their relatives are presented in Table 4. The main effect of the following variables on heavy smoking in the relatives was examined: heavy smoking, major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, alcohol use disorders, and drug use disorders in the probands and comorbid disorders in the relatives (i.e., major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, alcohol use disorders, and drug use disorders). In order to evaluate the impact of double depression in both probands and their relatives on the smoking status of the relatives, the interactions between major depression and dysthymia were also included in the model. Potential confounders, including proband and relative sex, age, and proband ascertainment source, were entered as covariates. Heavy smoking was found to aggregate in families, in that heavy smoking in probands was found to be significantly associated with heavy smoking in the relatives. When we examined the depressive disorders, dysthymia in the probands was significantly associated with heavy smoking in the relatives, suggesting that heavy smoking and dysthymia share a common etiology. In contrast, major depression and double depression in the probands was not found to increase the risk of smoking in the relatives. Both dysthymia and alcohol abuse or dependence were significantly associated with comorbid heavy smoking among the relatives; major depression and double depression were not. Because of the demonstrated role of conduct problems and socioeconomic status in the development of smoking behaviors, a history of conduct problems and lower socioeconomic status were also tested in subsequent models. Significant associations remained unchanged.

Discussion

When the associations between individual psychiatric disorders and heavy smoking were examined, only alcohol use disorders were found to be significantly associated with regular heavy smoking. While several previous epidemiologic studies have demonstrated an independent association between smoking and both alcohol use disorders and major depression (15, 17, 24), others have shown that depression is not significantly associated with smoking after adjustment for comorbidity (6, 25, 26). Accumulating research has begun to support the presence of an indirect relationship between smoking and depression. For example, on the basis of a longitudinal investigation of African American youth, Miller-Johnson and colleagues (27) found that depression was associated with subsequent tobacco use but only in the presence of comorbid conduct problems. Similarly, the findings reported by Breslau and colleagues (9) showed that a history of conduct problems was an influential predictor of both smoking and depression, accounting in part for their association. Patton and colleagues (28) also found that depression predicted smoking only in the presence of peer smoking.

Dysthymia and Heavy Smoking

When we consider the two explanations for comorbidity (either common risk factors or causal association), there was evidence of a shared etiology between dysthymia and heavy smoking on the basis of the significant cross-aggregation of these conditions in the probands and their relatives, a finding supported for major depression and smoking in previous studies (15, 17). One possible source of shared vulnerability extensively discussed in the literature is the genetic similarity among family members that may manifest in specific personality attributes (e.g., neurotic traits or negative affectivity) (29–31). There is evidence, for example, to suggest that personality traits underlie vulnerability for the development of depression (31, 32) and are responsible for individual differences in nicotine response (33). Although not directly tested, the role of negative affectivity in the association between dysthymia and heavy smoking does not seem to be supported by the present study. That is, higher levels of negative affectivity are most common among individuals expressing double depression; however, the co-occurrence of major depression and dysthymia was not found to be associated with heavy smoking.

Although dysthymia and major depression share common symptoms, dysthymia has been distinguished from major depression in its requirement of fewer associated symptoms and a more chronic course (DSM-IV). As was similar to findings from previous research (34, 35), subjects in the present study with both dysthymia and major depression exhibited significantly more lifetime impairment and an earlier age of onset of depressive symptoms than those with a lifetime history of only one of these disorders. Double depression was not, however, associated with heavy smoking among the relatives of the probands. Since the interaction between major depression and dysthymia was included in the present cross-aggregation models, the independent emergence of dysthymia in the probands and relatives as a significant predictor of heavy smoking among the relatives suggests that it may be the subthreshold nature of the condition rather than its chronicity that is associated with smoking. The relationship between lower levels of depressive symptoms and smoking has recently been demonstrated by Paeivaerinta and colleagues (36), who found a significant association between smoking and minor rather than major depressive disorder among older women. In contrast, Tanskanen and colleagues (18) found that rates of smoking were higher among severely depressed than among moderately depressed individuals.

Strengths and Limitations

The major strengths of this study include

1. Its application of family study design and methods to the study of mechanisms of comorbidity.

2. Its ascertainment of probands from both clinics and community settings, enhancing the generalizability of study results by minimizing potential selection biases inherent in most family studies derived from nonrepresentative groups.

3. Its use of multivariate models controlling for interrelationships among comorbid psychopathology and other potential confounders.

4. Its use of both psychiatric comparison and normal comparison groups, which prevents the exaggeration of differences between relatives of patients and comparison subjects.

Although the probands in the present family study were not selected specifically for the presence of depressive disorders or smoking status, these data afforded a unique opportunity to discriminate between alternative mechanisms of comorbidity on the basis of sufficient numbers of probands with a lifetime history of heavy smoking and/or depressive disorders. This study is only the second attempt of which we are aware to explore the mechanisms of comorbidity between smoking and depression and the first, to our knowledge, to apply family study methods to examine this important question.

The present results should be considered within the context of some basic limitations. First, this study included lifetime assessment procedures that necessarily rely on retrospective reporting of interrelated symptom profiles with complicated expressions and courses. The impact of subject age, recency of psychiatric or substance use episodes, and/or the extent of comorbidity may significantly affect the rates of false negatives. Second, although this was a high-risk study group, low rates of individual disorders did not allow for a careful consideration of possible sex differences. While these effects were controlled in each analysis, an exploration of interactions between sex and psychopathology remains an important direction for future research. Finally, our analyses are limited by the assessment parameters for the two conditions under study. While heavy smoking has been shown to overlap substantially with nicotine dependence, previous research has suggested that a subset of nicotine-dependent smokers reaches this threshold at lower levels of use. Furthermore, the one-pack-a-day cutoff dichotomized, somewhat arbitrarily, a naturally continuous variable that may in future investigations shed further light on the parameters of the smoking-depression relationship. Similarly, when we considered depression, our analyses were based on current definitions and subtypes reflected in the DSM taxonomy. Debate over whether depression is a single disease characterized by a continuum of symptoms or a subset of distinct diseases with unique clinical characteristics and courses has been abundant (37–39). Disentangling the association between depression and smoking may, in fact, require methods that are less bound by contemporary classification.

Implications

Although nicotine dependence has not historically been considered in the treatment of dual diagnoses (40), the evaluation of smoking in the context of psychiatric illness has become an extremely important issue for clinical psychiatry (41). Over the last two decades, greater knowledge surrounding the health risks associated with smoking, as well as the lower social acceptability of smoking—which has reduced the opportunities in which to smoke—has transformed this previously normative behavior into a more deviant behavior more consistently intertwined with psychiatric symptom profiles. Accumulating research has supported this assertion through stronger and more consistent smoking-psychopathology associations linked to the recency of cohorts (42). Furthermore, smoking has even been tied to the etiology of psychiatric disorders (43) and to the success of psychiatric treatments (44).

Investigations into the mechanisms of comorbidity have particularly important implications for prevention and treatment. If evidence for a direct or indirect causal link is established, intervention trials can be designed that focus on the primary prevention of the secondary condition (45). Similarly, if a shared etiology is supported, intervention may focus on gene-by-environment interactions that are believed to play a role in the development of both conditions. Outcome evaluations of these interventions can then supply further evidence for the appropriateness of identified mechanisms. Rather than providing evidence for specific intervention targets or content, the present findings emphasize the complexity of the topic and suggest a need for continued research attention.

Conclusions

The present study suggests different mechanisms for comorbidity between smoking and depression for specific subtypes of depressive disorders. There was found evidence of shared etiologic factors between dysthymia and heavy smoking, whereas there did not appear to be a shared vulnerability between major and double depression and heavy smoking. This report contributes to the accumulating literature on the co-occurrence of smoking and depression by providing preliminary evidence for a common diathesis between them. Moreover, it clearly demonstrates the need for continued genetic epidemiological work including large and diverse study groups with adequate prevalence rates and careful assessment of each phenotype.

|

|

|

|

Received May 22, 2001; revision received Sept. 4, 2001; accepted Oct. 19, 2001. From the Department of Psychology, Wesleyan University; and Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Dierker, Department of Psychology, Wesleyan University, 207 High St., Middletown, CT 06459; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by a Faculty Scholars Award from the Tobacco Etiology Research Network of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Dr. Dierker) and by grants DA-05348 and DA-09055 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, MH-30929 from NIMH, CA-84719 from the National Cancer Institute, and AA-07080, AA-09978, and AA-12044 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

1. Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR: Psychiatric comorbidity with problematic alcohol use in high school students. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:101-109Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Costello J, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A: Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: effects of timing and sex. J Clin Child Psychol 1999; 28:298-311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Grant BF: Comorbidity between DSM-IV drug use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey of adults. J Subst Abuse 1995; 7:481-497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA 1990; 264:2511-2518Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Swendsen JD, Merikangas KR: The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clin Psychol Rev 2000; 20:173-189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Wagner EF: Cigarette smoking, major depression, and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:1602-1610Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ: Comorbidity between depressive disorders and nicotine dependence in a cohort of 16-year-olds. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1043-1047Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P: Nicotine dependence and major depression: new evidence from a prospective investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:31-35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P: Major depression and stages of smoking: a longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:161-166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kandel DB, Johnson JG, Bird HR, Canino G, Goodman S, Lahey B, Regier D, Schwab-Stone M: Psychiatric disorders associated with substance use among children and adolescents: findings from the Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) Study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1997; 25:121-132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Gilbert DG: Paradoxical tranquilizing and emotion-reducing effects of nicotine. Psychol Bull 1979; 86:643-661Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Carmody TP: Affect regulation, nicotine addiction, and smoking cessation. J Psychoactive Drugs 1989; 21:331-342Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS: Neuroregulators and the reinforcement of smoking: towards a biobehavioral explanation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1984; 8:503-513Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Henningfield JE, Miyasato K, Jasinski DR: Abuse liability and pharmacodynamic characteristics of intravenous and inhaled nicotine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1985; 234:1-12Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, Heath AC, Eaves L, Kessler R: Smoking and major depression: a causal analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:36-43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P: Nicotine dependence, major depression, and anxiety in young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1069-1074Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Breslau N: Psychiatric comorbidity of smoking and nicotine dependence. Behav Genet 1995; 25:95-101Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Tanskanen A, Viinamaeki H, Koivumaa-Honkanen H-T, Hintikka J, Jaeaeskelaeinen J, Lehtonen J: Smoking and depression among psychiatric patients. Nord J Psychiatry 1999; 53:45-48Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Merikangas KR: The genetic epidemiology of alcoholism. Psychol Med 1990; 20:11-22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Merikangas KR, Stevens DE, Fenton B, O’Malley S, Stolar M, Wood S, Risch N: Comorbidity and familial aggregation of alcoholism and the anxiety disorders. Psychol Med 1998; 28:773-788Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837-844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G: The family history method using diagnostic criteria: reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:1229-1235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Wacholder S: Binomial regression in GLIM: estimating risk ratios and risk differences. Am J Epidemiol 1986; 123:174-184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J: Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA 1990; 264:1546-1549Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Federman EB, Costello EJ, Angold A, Farmer EMZ, Erkanli A: Development of substance use and psychiatric comorbidity in an epidemiologic study of white and American Indian young adolescents: the Great Smoky Mountains Study. Drug Alcohol Depend 1997; 44:69-78Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Black DW, Zimmerman M, Coryell WH: Cigarette smoking and psychiatric disorder in a community sample. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1999; 11:129-136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Miller-Johnson S, Lochman JE, Coie JD, Terry R, Hyman C: Comorbidity of conduct and depressive problems at sixth grade: substance use outcomes across adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1998; 26:221-232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Patton GC, Carlin JB, Coffey C, Wolfe R, Hibbert M, Bowes G: Depression, anxiety, and smoking initiation: a prospective study over 3 years. Am J Public Health 1998; 88:1518-1522Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Gilbert DG, Gilbert BO: Personality, psychopathology, and nicotine response as mediators of the genetics of smoking. Behav Genet 1995; 25:133-147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Sieber MF, Angst J: Alcohol, tobacco and cannabis: 12-year longitudinal associations with antecedent social context and personality. Drug Alcohol Depend 1990; 25:281-292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: Major depression and generalized anxiety disorder: same genes, (partly) different environments? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:716-722Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Wallace JF, Newman JP: Neuroticism and the attentional mediation of dysregulatory psychopathology. Cognitive Therapy and Res 1997; 21:135-156Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Gilbert DG, Meliska CJ, Welser R, Estes SL: Depression, personality, and gender influence EEG, cortisol, beta-endorphin, heart rate, and subjective responses to smoking multiple cigarettes. Pers Individ Dif 1994; 16:247-264Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Leader JB, Klein DN: Social adjustment in dysthymia, double depression and episodic major depression. J Affect Disord 1996; 37:91-101Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, Paulus MP, Kunovac JL, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Rice JA, Keller MB: A prospective 12-year study of subsyndromal and syndromal depressive symptoms in unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:694-700Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Paeivaerinta A, Verkkoniemi A, Niinistoe L, Kivelae SL, Sulkava R: The prevalence and associates of depressive disorders in the oldest-old Finns. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34:352-359Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Winokur G: All roads lead to depression: clinically homogeneous, etiologically heterogeneous. J Affect Disord 1997; 45:97-108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Paulus MP: The role and clinical significance of subsyndromal depressive symptoms (SSD) in unipolar major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 1997; 45:5-17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Kendler KS, Gardner CO Jr: Boundaries of major depression: an evaluation of DSM-IV criteria. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:172-177Abstract, Google Scholar

40. Evans K, Sullivan JM: Dual Diagnosis: Counseling the Mentally Ill Substance Abuser, 2nd ed. New York, Guilford, 2001Google Scholar

41. Glassman AH: Cigarette smoking: implications for psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:546-553Link, Google Scholar

42. Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hiripi E, Kessler R: Nicotine dependence in the United States: prevalence, trends, and smoking persistence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:810-816Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS: Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA 2000; 284:2348-2351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Parrott AC: Does cigarette smoking cause stress? Am Psychol 1999; 54:817-820Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Kessler RC, Price RH: Primary prevention of secondary disorders: a proposal and agenda. Am J Community Psychol 1993; 21:607-633Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar