Comparative Study of Trauma-Related Phenomena in Subjects With Pseudoseizures and Subjects With Epilepsy

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to examine potential differences in measures of trauma-related phenomena between subjects with pseudoseizures and subjects with intractable epilepsy. METHOD: Thirty-one adult subjects with pseudoseizures and 32 subjects with intractable epilepsy (confirmed by video-EEG) were recruited from the epilepsy unit of a tertiary care hospital. Each participant completed the Impact of Event Scale, the Davidson Trauma Scale, the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the Dissociative Experience Scale, and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, as well as demographic, seizure history, and family functioning measures. RESULTS: Subjects with pseudoseizures had significantly higher mean scores on the Davidson Trauma Scale, Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD, Impact of Event Scale, and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index than subjects with epilepsy. In addition, a significantly higher percentage of subjects with pseudoseizures had scores above the clinical cutoff level of 30 on the Dissociative Experience Scale. CONCLUSIONS: Subjects with pseudoseizures exhibited trauma-related profiles that differed significantly from those of epileptic comparison subjects and closely resembled those of individuals with a history of traumatic experiences. Interventions aimed at trauma-related issues may be beneficial for patients with pseudoseizures.

Pseudoseizures may be defined as paroxysmal behavioral changes, resembling epileptic seizures, for which no satisfactory organic basis can be found. Although many such definitions of pseudoseizures imply that there is an absence of comorbid organic diathesis, some researchers have postulated a model that would include impairment of CNS mechanisms (1, 2). These findings as well as other research (3, 4) suggest that pseudoseizures have an underlying psychiatric mechanism that may be related to past or current traumatic experiences. Evidence to support this theory derives from a number of lines of research.

Clinical studies of subjects with pseudoseizures (3–5) have found high rates of sexual abuse, physical abuse, and other trauma, with incidences approaching 66%–88%. Women in these studies reported significantly more physical abuse, sexual abuse, and total trauma than men. Two studies comparing patients with pseudoseizures and patients with epilepsy (6, 7) reported that the patients with pseudoseizures were more likely to have histories of physical or sexual abuse. Related research (3, 8) has shown that the onset of pseudoseizures is associated with a recent acute stress situation in 70%–85% of such subjects.

Studies have also examined the psychiatric diagnoses of pseudoseizure patients. The most common associated diagnoses were depression (1, 9, 10), anxiety (1, 10), conversion or somatization symptoms (1, 8, 9), and dissociative disorders (11). Studies conducted by Bowman and Markand (3, 4) examined the psychiatric profile of patients with pseudoseizures in more detail. The most common psychiatric diagnoses were affective disorders (80%–85%), dissociative disorders (85%–93%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (33%–58%). In addition, scores on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders showed that pseudoseizure patients had more dissociative pathology than general psychiatric outpatients (3). Interestingly, all of the subjects with histories of sexual or physical abuse had dissociative disorders (4).

Some of the limitations of the studies cited include relatively small sample sizes, unclear or unspecified diagnostic evaluation criteria, and retrospective designs. Nevertheless, the research to date suggests that traumatic experiences play an important role in the development and expression of pseudoseizure symptoms. To investigate this hypothesis, we administered a number of established standardized psychometric instruments measuring trauma-related phenomena to a group of subjects with pseudoseizures and a comparison group of subjects with epilepsy.

Method

Adult subjects with pseudoseizures and comparison subjects with intractable epilepsy (confirmed with video-EEG) were recruited through the Epilepsy Unit of a tertiary care hospital over a 4-year period. The diagnosis of pseudoseizure was made if at least two stereotypic events, consisting of apparent altered awareness, behavioral changes, and an absence of associated paroxysmal epileptiform changes, were recorded on video-EEG and interpreted by a qualified epileptologist. Individuals in whom the EEG was technically unsatisfactory or equivocal were excluded from the study. Subjects who met the criteria for both pseudoseizures and epilepsy were included in the pseudoseizure group. All subjects who agreed to participate in our study were fully informed about the scales involved and how they might be used. Full verbal and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Eligible participants completed the Impact of Event Scale (12), the Davidson Trauma Scale (13), the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (14), the Dissociative Experience Scale (15), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (16). Subjects also provided basic demographic information and a seizure history and completed two measures of family functioning. These latter results have been reported elsewhere (17).

Differences in the psychometric measures between the pseudoseizure and comparison groups were compared by independent-groups t tests with two-tailed probabilities and with the Bonferroni correction for multiple inferences. Differences in demographic measures were assessed with chi-square tests.

Results

The mean age of the pseudoseizure group (36.7 years, SD=8.5) was similar to the mean age of the epileptic comparison group (37.2 years, SD=10.4). There were 11 men and 20 women in the pseudoseizure group and 10 men and 22 women in the comparison group. Furthermore, there were no significant differences between the subjects with pseudoseizures and those with epilepsy in terms of marital status, employment status, education, income, or status regarding provision of social assistance.

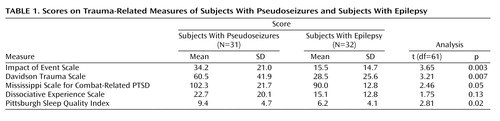

Table 1 presents the mean scores for the two groups on the five psychometric measures. The subjects with pseudoseizures scored significantly higher on the Impact of Event Scale, the Davidson Trauma Scale, the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD, and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Although the difference in mean scores between groups on the Dissociative Experience Scale was not statistically significant, a higher percentage of subjects with pseudoseizures (64.5%, N=20) than of subjects with epilepsy (37.5%, N=12) had scores above the clinically significant cutoff score of 30 or greater (χ2=6.23, df=1, p<0.01).

Discussion

The results clearly show that the majority of self-report trauma-related psychometric scales discriminate between clinical groups with pseudoseizures and epilepsy. The greatest statistical difference was noted on the Impact of Event Scale, which measures the current subjective impact of specific stressful life events.

Both the Davidson Trauma Scale and Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD, which evaluate the frequency and severity of PTSD symptoms on the basis of DSM-IV and DSM-III criteria, respectively, differentiated between the pseudoseizure and epileptic subjects. This is consistent with the hypothesis that traumatic experiences are important precursors to the development and expression of pseudoseizure symptoms (3, 4).

The subjects with pseudoseizures also reported greater sleep disturbance patterns, as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, than subjects with epilepsy. There is considerable evidence that several indexes of sleep disturbance and dysfunction are associated with PTSD (18).

For comparison purposes, Table 2 presents mean scores on the five psychometric measures for normative and clinical samples reported in the literature. The mean scores for the subjects with pseudoseizures in the present study more closely resemble a profile associated with stress (Impact of Event Scale), a PTSD diagnosis based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Davidson Trauma Scale), behavioral and psychological problems (Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD), and sleep disturbance (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) than the mean scores of epileptic subjects. Scores on the Dissociative Experience Scale for the pseudoseizure group were very similar to those reported for subjects with pseudoseizures (3, 4) and approach the level reported for PTSD clinical samples (19).

Some comments on the use of epileptic subjects as a comparison group are warranted. Although not documented in the literature, one could hypothesize that because of their medical condition, subjects with epilepsy may inherently share symptoms often attributable to trauma-related phenomena (e.g., affective dysregulation, excessive irritability, and dissociative experiences). Consequently, comparisons of subjects with pseudoseizures and epileptic subjects may yield smaller potential differences than would a comparison of pseudoseizure subjects with a nonclinical group.

A number of limitations of the study should be noted. First, the pseudoseizure group contained a mixture of subjects with pseudoseizures without epilepsy and subjects who met the criteria for both pseudoseizures and epilepsy. Second, the measures of trauma-related phenomena were all standardized self-report measures without confirmation by structured interviews. Finally, there was no measure of exposure to adverse events to associate with the self-reported incidences of PTSD phenomenology.

Despite these limitations, our results indicate that subjects with pseudoseizures have significantly higher levels of trauma-related phenomenology than epileptic subjects and have symptom profiles that closely resemble those of clinical samples of subjects with PTSD. Given the known comorbid sequelae of various forms of abuse, it would be possible to speculate that a subgroup of those who are sexually abused in childhood are also physically abused in ways that might lead to subtle CNS neurophysiological changes. The potential vulnerability to mood and cognitive dysregulation associated with such abuses could give rise to both psychological and subtle physiological seizure-like symptoms in this population. Further research with subjects with pseudoseizures and those with epilepsy is warranted, including structured interviews to determine more precisely the nature and effect of traumatic events and studies of both brain structure and function to examine possible shared CNS features. Comparison of neuroanatomical and brain function measures between subjects with PTSD and those with pseudoseizures would also be indicated to further delineate any potentially shared brain properties.

|

|

Presented in part at the 48th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Psychiatric Association, Halifax, N.S., Sept. 15–18, 1998. Received Oct. 20, 2000; revision received Aug. 24, 2001; accepted Nov. 15, 2001. From the Departments of Psychiatry, Internal Medicine (Section of Neurology), and Clinical Health Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba; and the Mental Health Program, St. Boniface General Hospital, Winnipeg. Address reprint requests to Dr. Fleisher, PZ-162, 771 Bannatyne Ave., Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3E 3N4.

1. Blumer D: The paroxysmal somatoform disorder: a series of patients with non-epileptic seizures, in Non-Epileptic Seizures. Edited by Rowan AJ, Gates JR. Boston, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993, pp 165-172Google Scholar

2. Blumer D: On the psychobiology of non-epileptic seizures, in Non-Epileptic Seizures, 2nd ed. Edited by Rowan AJ, Gates JR. Boston, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000, pp 305-310Google Scholar

3. Bowman ES, Markand ON: Psychodynamics and psychiatric diagnoses of pseudoseizure subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:57-63Link, Google Scholar

4. Bowman ES: Etiology and clinical course of pseudoseizures: relationship to trauma, depression and dissociation. Psychosomatics 1993; 34:333-342Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Shen W, Bowman ES, Markand O: Presenting the diagnosis of pseudoseizure. Neurology 1990; 40:756-759Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Alper K, Devinsky O, Perrine K, Vazquez B, Luciano D: Non-epileptic seizures and childhood sexual and physical abuse. Neurology 1993; 43:1950-1953Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kuyk J, Spinhoven P, van Erode Boas W, van Dyck R: Dissociation in temporal lobe epilepsy and pseudo-epileptic seizure patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:713-720Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Drake ME, Pakalnis A, Phillips B: Neuropsychological and psychiatric correlates of intractable pseudoseizures. Seizure 1992; 1:11-13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Meierkord H, Will B, Fish D, Shorvon S: The clinical features and prognosis of pseudoseizures diagnosed using video-EEG telemetry. Neurology 1991; 41:1643-1646Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Roy A, Barris M: Psychiatric concepts in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, in Non-Epileptic Seizures. Edited by Rowan AJ, Gates JR. Boston, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993, pp 143-151Google Scholar

11. Ramchandani D, Schindler B: Evaluation of pseudoseizures: a psychiatric perspective. Psychosomatics 1993; 34:70-79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41:209-218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Davidson JRT, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, Davis D, Hertzberg M, Mellman T, Beckham JC, Smith RD, Davison RM, Katz R, Feidman ME: Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med 1997; 27:153-160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Keane TM, Caddell JM, Taylor KL: Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: three studies in reliability and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:85-90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW: Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:727-735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Buysse DJ, Reynolds C, Monk T, Berman SR, Kupfer D: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989; 28:193-213Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Krawetz P, Fleisher W, Pillay N, Staley D, Arnett J, Maher J: Family functioning in patients with pseudoseizures and epilepsy. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001; 89:38-43Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Ross RJ, Ball WA, Sullivan KA, Caroff SN: Sleep disturbance as the hallmark of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:697-707Link, Google Scholar

19. Putnam F, Carlson E, Ross CA, Anderson G, Clark P, Torero M, Bowman ES, Coons P, Chu JA, Dill D, Loewenstein RJ, Braun BG: Patterns of dissociation in clinical and nonclinical samples. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184:673-679Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar