Influence of Gender on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children Referred to a Psychiatric Clinic

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The substantial discrepancy in the male-to-female ratio between clinic-referred (10 to 1) and community (3 to 1) samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) suggests that gender differences may be operant in the phenotypic expression of ADHD. In this study the authors systematically examined the impact of gender on the clinical features of ADHD in a group of children referred to a clinic. METHOD: The study included 140 boys and 140 girls with ADHD and 120 boys and 122 girls without ADHD as comparison subjects. All subjects were systematically assessed with structured diagnostic interviews and neuropsychological batteries for subtypes of ADHD as well as emotional, school, intellectual, interpersonal, and family functioning. RESULTS: Girls with ADHD were more likely than boys to have the predominantly inattentive type of ADHD, less likely to have a learning disability, and less likely to manifest problems in school or in their spare time. In addition, girls with ADHD were at less risk for comorbid major depression, conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder than boys with ADHD. A statistically significant gender-by-ADHD interaction was identified for comorbid substance use disorders as well. CONCLUSIONS: The lower likelihood for girls to manifest psychiatric, cognitive, and functional impairment than boys could result in gender-based referral bias unfavorable to girls with ADHD.

Despite the fact that a large number of girls might be suffering from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the scientific literature on ADHD is almost exclusively based on boys. To address the paucity of information on ADHD in girls, in an earlier study (1) we compared the clinical correlates of ADHD in a large group of girls with and without ADHD ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric facilities. This study showed that ADHD in girls was characterized by prototypical symptoms of the disorder, comorbid psychopathology, social dysfunction, cognitive impairments, school failure, and adversity in the family environment.

Despite this level of dysfunction, a substantial discrepancy exists in the male-to-female ratio between clinic-referred (10 to 1) and community (3 to 1) samples of children with ADHD (2, 3). Although the reasons for the apparent underidentification of girls with ADHD remain unclear, Gaub and Carlson (3) suggested in their meta-analysis that gender differences in the phenotypic expression of the disorder may be driving referral of more boys than girls. However, Gaub and Carlson also pointed out that the dearth of research comparing boys and girls with ADHD limits the conclusions that can be drawn from the extant literature. In addition to the scarcity of such studies, the previous studies of gender and ADHD that have been published are limited by small sample sizes, a limited scope of assessment, and the absence of gender-matched comparison subjects (4). These limitations impede an adequate understanding of gender effects and the ability to separate gender effects on ADHD from the main effect of gender within ADHD subjects.

In view of the importance of early and appropriate treatments for ADHD, a comprehensive understanding of gender differences and similarities in the clinical manifestations of ADHD has major public health and scientific importance for the advancement of women’s health. To this end, we systematically compared boys and girls with and without ADHD in multiple domains of functioning. We hypothesized that ADHD in girls would be characterized by lower rates of comorbid disruptive behavior disorder, a preponderance of the inattentive subtype of ADHD, and less cognitive dysfunction than ADHD in boys.

Method

Subjects

Data from two identically designed family studies of ADHD (1, 5) were combined. Our first study (5) ascertained boys with or without ADHD who were 6–17 years old at the time of ascertainment; this study included 140 boys with ADHD and 120 boys without ADHD. Our second study (1) ascertained girls with and without ADHD who were also 6–17 years old at the time of ascertainment; this study included 140 girls with ADHD and 122 girls without ADHD.

Ascertainment

Potential subjects were excluded from both studies if they had been adopted or if their nuclear family was not available for study. We excluded subjects if they had major sensorimotor handicaps (paralysis, deafness, blindness), psychosis, autism, inadequate command of the English language, or a full-scale IQ (6) less than 80. Parents provided written informed consent for their children, and children and adolescents provided written assent to their participation.

Two independent sources provided the children with ADHD. We selected psychiatrically referred children with ADHD from consecutive referrals to a pediatric psychopharmacology clinic at the Massachusetts General Hospital (selection criteria are described later in this article). Parents, pediatricians, and schools had referred these children for psychiatric evaluations. The other source of children with ADHD were pediatric patients from a health maintenance organization (HMO). Within each setting, we selected comparison subjects without ADHD from outpatients at pediatric medical clinics.

A three-stage ascertainment procedure was used to select the subjects. For children with ADHD, the first stage was the patient’s referral to a psychiatric or pediatric clinic resulting in a clinical diagnosis of ADHD by a child psychiatrist or pediatrician, which was recorded in the clinic record. A second stage confirmed the diagnosis of ADHD after all children with a positive diagnosis at the first stage were screened by administering a telephone questionnaire asking the child’s mother about the 14 DSM-III-R symptoms of ADHD. The third stage confirmed the diagnosis made on the basis of the telephone questionnaire with face-to-face structured interviews with the mother. Only patients who received a diagnosis of ADHD at all three stages were included in the final analysis. Comparison subjects without ADHD were ascertained from referrals to medical clinics for routine physical examinations at both the Massachusetts General Hospital and the HMO sites. The mothers of these children were also interviewed by telephone and face-to-face; children included in the study did not meet ADHD criteria at any of the three stages.

Measures

Psychiatric assessments of the children were made by using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E) (7). Diagnoses were based on independent interviews with the mothers and direct interviews with the children older than 12 years. Diagnostic assessments of parents were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (8) conducted with each parent. To assess childhood diagnoses in the parents, modules from the K-SADS-E covering childhood diagnoses were administered. All assessments were made by raters who were blind to the child’s diagnosis (ADHD or no ADHD) and ascertainment site. Different interviewers met with mothers and children to maintain blindness to ADHD status and to prevent information from one informant influencing the assessment of the other.

A committee of three psychiatrists (J.B., T.S., and T.E.W.), each board certified in both child and adult psychiatry, resolved all diagnostic uncertainties. The committee members were blind to the subjects’ ascertainment group, ascertainment site, all data collected from family members, and all nondiagnostic data (e.g., neuropsychological tests). Kappa coefficients of agreement were computed between raters and three board-certified psychiatrists who listened to audiotaped interviews made by the raters. Based on 173 interviews, the median kappa was 0.86; for ADHD, kappa=0.99; for conduct disorder, kappa=0.93; for multiple anxiety disorders, kappa=0.80; for major depression, kappa=0.83; and for bipolar disorder, kappa=0.94. These statistics for multiple raters rating the same interview show excellent agreement of ratings but do not address the degree of agreement that would be attained between two separate interviews of the same patient.

In addition to psychiatric data, we assessed social functioning with the Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (9), socioeconomic status with the Hollingshead scale (10), divorce or separation of parents in family of origin, the family environment with the Family Environment Scale (11), indicators of social adversity from Rutter’s Isle of Wight study (12), perinatal complications with the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—Parent Version (13, 14), full-scale IQ based on the vocabulary and block design subtests of the Wechsler intelligence tests (15), reading and arithmetic achievement with subtests of the Wide Range Achievement Test, Revised (16), adaptive functioning with the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (DSM-III-R), and school difficulties (special class, repeated grades, tutoring) with structured diagnostic interview of the mother. The definition of learning disabilities under Public Law 94-142 requires a substantial discrepancy between a child’s potential and achievement (17). We operationalized this with the procedure recommended by Reynolds (18) that we have used elsewhere (19).

Statistical Analysis

Our main hypothesis was that there is no difference between boys and girls with respect to the impact that ADHD exerts on functioning in multiple domains. Data from comparison subjects without ADHD are presented so that interactions could be tested to determine if ADHD is a similar risk factor in boys and girls with respect to sex-matched children without ADHD. To determine if girls with ADHD have different clinic presentations from boys with the disorder, we also present within-ADHD between-gender pairwise comparisons. Binary data were analyzed with logistic regression models, and continuous data were analyzed with ordinary least-squares regression. Wald’s chi-square test was used to determine statistical significance. The effects of gender within the ADHD groups were tested with pairwise comparisons by using Pearson’s chi-square or analysis of variance for binary and continuous data, respectively. Statistical significance was determined at p<0.05.

Results

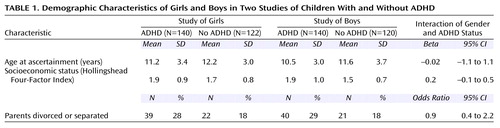

Demographic characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1. Although subjects from the study of girls with and without ADHD were slightly older than the subjects from the study of boys, the interaction between gender and ADHD status was not statistically significant. This indicated that the distance in age between the girls with and without ADHD was not different from the distance between the boys with and without ADHD. Likewise, ADHD was not associated with lower socioeconomic status and divorce or separation differently in boys and girls. We also failed to identify any statistically significant differences in demographic variables in pairwise comparisons of boys and girls with ADHD (Table 1).

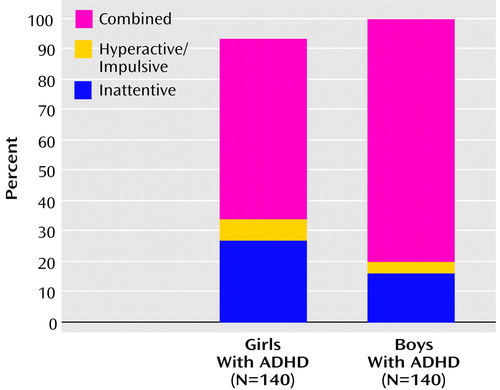

Comparisons of children with and without ADHD for both studies were ascertained by using DSM-III-R criteria for ADHD, which did not distinguish the subtypes of the disorder introduced in DSM-IV. However, additional symptoms required to make DSM-IV diagnoses were collected in the study of girls, and proxies for the subtypes were available for the study of boys (20). More girls who met DSM-III-R criteria for ADHD failed to meet DSM-IV criteria for ADHD (N=11 [8%]) than boys who met DSM-III-R criteria (N=1 [0.7%]). Although the combined type was the most prevalent type for both boys and girls with ADHD, girls with ADHD were 2.2 times (95% confidence interval=1.2–4.0) more likely to be diagnosed as primarily inattentive than were boys with ADHD (Figure 1).

Girls with ADHD were statistically but not clinically meaningfully older at onset of ADHD than boys with ADHD (mean=3.5 years, SD=2.5, versus mean=2.7, SD=2.0) (t=–3.0, df=277, p=0.003). Although all of the children with ADHD were from clinical settings, there were differences in the rates of medication and psychotherapy targeted for ADHD between boys and girls. The majority of both boys and girls received treatment, but girls were less likely to receive pharmacotherapy (70% [N=98] versus 82% [N=115]) (χ2=5.7, df=1, p=0.02) and psychotherapy (51% [N=71] versus 64% [N=89]) (χ2=5.7, df=1, p=0.02). However, the mean number of years from the onset of ADHD to the first encounter with treatment for the disorder was not different in girls and boys with ADHD (mean=4.5, SD=3.5, versus mean=3.1, SD=2.0) (t=0.1, df=203, p=0.9).

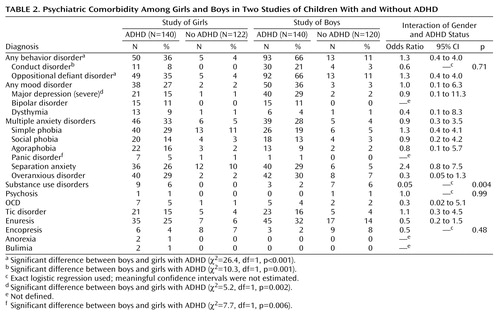

The profile of psychiatric comorbidity of ADHD was quite similar in boys and girls (Table 2). For substance use disorders there was a significant gender-by-diagnosis interaction, indicating that ADHD was a significantly weaker risk factor for substance use disorders in boys than it was in girls. The odds ratio of 0.05 indicates that ADHD increased the risk for substance use disorders one-20th as much in boys as it increased the risk for substance use disorders in girls. For other disorders the gender-by-diagnosis interaction was not significant, indicating that other gender differences between boys and girls with ADHD were the same as the gender difference observed for boys and girls without ADHD.

For example, girls with ADHD were at significantly lower risk for any other behavior disorder than boys with ADHD. This is a result of a naturally lower base rate of behavior disorders in girls regardless of ADHD status. Similar results were observed for conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, major depression, and (in the opposite direction) panic disorder.

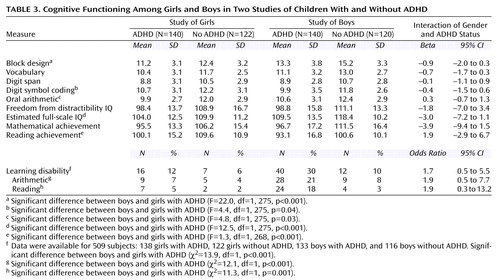

The children’s scores on the subscales of the WISC-R (6) are presented in Table 3. Again, gender did not modify the impact of ADHD on measures of intelligence (no gender-by-ADHD diagnosis interactions were statistically significant). However, girls with ADHD had statistically significantly, but not clinically meaningful, lower scores than boys with ADHD for estimated full-scale IQ and the block design, and oral arithmetic subscales. Boys with ADHD had significantly lower scores on reading achievement and significantly greater rates of learning disability than girls with ADHD, however (Table 3).

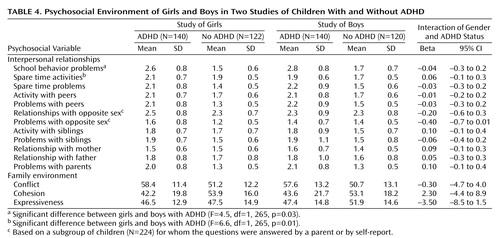

Although there were no gender-by-ADHD interactions for any of the psychosocial functioning items studied (Table 4), girls with ADHD had fewer school problems and participated in more spare-time activities than boys with ADHD. Despite the differences in the rate of psychiatric comorbidity and slightly lower intellectual functioning, there were no gender-by-ADHD interactions for indexes of the family environment, nor were there any pairwise differences between boys and girls with ADHD.

For each statistically significant within-ADHD gender difference we evaluated the impact of the higher rate of the inattentive subtype of ADHD in girls (data not presented). In no case was a gender difference found to be accounted for by subtype differences between boys and girls.

Discussion

ADHD in girls was more likely to be predominantly the inattentive subtype, less likely to be associated with a learning disability in reading or mathematics, and less likely to be associated with problems in school or fewer spare-time activities than ADHD in boys. Since these gender differences were apparent in the absence of gender-by-ADHD interactions, our results suggest that the risk for ADHD-associated impairments may be similarly elevated in both boys and girls, but that gender-specific variation in baseline risks may result in different rates of psychiatric morbidity and dysfunction that may adversely affect the identification of the disorder in girls.

The single statistically significantly gender-by-ADHD interaction identified was the association between ADHD and substance use disorders (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence). That ADHD in girls was a more serious risk factor for substance use disorders than it was in boys was an unanticipated and surprising finding. In the light of ongoing concerns regarding ADHD as a putative risk factor for substance use disorders (21), this finding may indicate that girls are particularly at risk in early adolescence. Given that the ages at onset of ADHD and substance use disorders are separated by at least a decade (22, 23), this finding would support the targeting of substance abuse prevention programs to girls with ADHD.

With the single exception of substance use disorders, however, no statistically significant gender-by-ADHD interactions were identified in the multiple outcomes evaluated. These results suggest that with the exception of substance use disorders, ADHD expresses itself similarly in boys and girls relative to comparison subjects of the same gender, indicating that ADHD-associated impairments are correlates of ADHD in both boys and girls. However, between-gender differences were identified among the children with ADHD, such as the higher rate among girls of symptoms of inattention and lower rates of comorbidity with disruptive behavior disorders, major depression, and learning disabilities. Since these differences were attributable to the main effects of gender rather than modification of the ADHD effect by gender, these findings indicate that girls were at the same relative risk for these adverse outcomes as boys but that girls had different clinical presentations.

For example, although girls with ADHD were at significantly greater risk for disruptive behavior disorders (conduct and oppositional defiant disorder) than girls without ADHD (1), disruptive behavior disorders were clearly less prevalent in girls, regardless of ADHD status. As suggested by Gaub and Carlson (3), the lower risk of disruptive behavior disorders in girls could have led to the underidentification and underreferral of girls with ADHD because clinical referrals are often based on overt problem behavior and aggression. Consistent with this suggestion, girls with ADHD had fewer school problems and participated in more spare-time activities than boys with ADHD.

Furthermore, our results show that, although the combined type of ADHD was the predominant type in both girls and boys, girls with ADHD were twice as likely as boys with ADHD to manifest the predominantly inattentive type of the disorder. Since symptoms of inattention are more covert than those of hyperactivity and impulsivity, the higher rate of these symptoms in girls with ADHD than in boys with ADHD may also partially explain the markedly higher male-to-female ratios in groups of children who are clinically referred for ADHD than in children with the disorder who are not clinically referred.

Although girls with ADHD had statistically significantly lower IQs than boys, these differences were small and of limited clinical significance. These results are largely consistent with those of other studies that have failed to identify meaningful effects of gender on cognitive performance (24, 25), but we found that girls with ADHD had significantly lower rates of psychometrically defined learning disabilities, reflecting the absence of a significant discrepancy between IQ and achievement scores in reading and mathematics. Since academic underachievement represents another leading reason for parents and teachers to seek help for children with ADHD, the markedly lower rate of learning disability in girls with this disorder may also decrease identification of ADHD in girls.

Girls with ADHD were at significantly greater risk for comorbid major depression than girls without ADHD (1) but had a significantly lower rate of comorbid major depression than boys with ADHD. This finding was not anticipated, since depression is commonly viewed as a predominantly female disorder (26). Although the reasons for this result are not entirely clear, it is consistent with findings documenting that prepubertal-onset major depression is largely male predominant (27). More consistent with the adult literature is the finding of a higher rate of panic disorder in girls with ADHD than in boys with ADHD. The extant literature documents a higher rate of panic disorder in females over males, regardless of age (28).

Modest but statistically significant differences were observed in the treatment variables examined: boys with ADHD tended to receive more pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy than girls with the disorder. Although this result suggests that girls are less likely to receive appropriate treatment for ADHD, the differences observed between boys and girls were quite small and are not consistent with the notion of inadequate treatment of girls with ADHD. Rather, these findings could be interpreted as suggesting that, once identified, ADHD may be treated similarly in boys and girls.

Our results must be viewed in the light of some methodological limitations. Because only Caucasian subjects were included, our results do not generalize to children of other racial or ethnic backgrounds. Since these results are cross-sectional, we cannot test the longitudinal impact of gender on ADHD or the relative effect of treatment in girls and boys. Our assessments relied on indirect parental reports and direct interviews with those children older than 12 years (half of the children studied) but did not include information collected from teachers or younger children. This limitation is not likely to affect the findings presented here because 1) both boys and girls were subjected to the same methods, 2) we have found parent reports to be very reliable and stable over time in our studies (29), and 3) others have raised questions regarding the validity of reports taken from very young children (30).

In this study, children who met DSM-III-R criteria for ADHD but not DSM-IV criteria were included in the analysis. We did not use DSM-IV criteria to define ADHD in the study groups in this report because both samples were ascertained on the basis of DSM-III-R. On the basis of previous work showing that DSM-III-R-diagnosed ADHD is highly convergent with DSM-IV-diagnosed ADHD in both boys and girls (positive predictive value of 93%) (1, 31), we believe that these results are informative today. The groups of boys and girls were also ascertained 5 years apart from each other, so that cohort effects could be misconstrued as gender effects. Although the baseline risk of psychopathology and other functional characteristics examined here could be expected to change with time, the odds ratio in contemporaneous comparison subjects should stay constant. Thus, if we assume that there are no other confounding variables, a statistically significant interaction could not be due to a cohort effect and may reasonably be attributed to gender. In addition, we could not specifically test the hypothesis that girls are underidentified because all of the children with ADHD were referred for treatment.

Despite these considerations, our results suggest that although gender is a limited effect modifier of ADHD as a risk factor for ADHD-associated dysfunction in referred children and adolescents, gender did have an effect on the clinical presentation of the disorder. This was largely due to the finding that girls with ADHD were less likely than boys with ADHD to have comorbid disruptive behavior problems, learning disabilities, and social dysfunction and that the rate of symptoms of inattention was higher in girls with ADHD. Since these features could result in a gender-based referral bias unfavorable to girls, more work is needed in both referred and nonreferred samples of children with ADHD to assess this issue more fully.

|

|

|

|

Received Nov. 27, 2000; revision received April 10, 2001; accepted June 26, 2001. From the Pediatric Psychopharmacology Unit, Child Psychiatry Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School. Address reprint requests to Dr. Biederman, Pediatric Psychopharmacology Unit (WACC 725), Massachusetts General Hospital, 15 Parkman St., Boston, MA 02114; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant HD-36317 and NIMH grant MH-50657 (Dr. Biederman).

Figure 1. DSM-IV Subtypes of ADHD in Boys and Girls in Two Studies of Children With DSM-III-R ADHD

1. Biederman J, Faraone S, Mick E, Williamson S, Wilens T, Spencer T, Weber W, Jetton J, Kraus I, Pert J, Zallen B: Clinical correlates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in females: findings from a large group of pediatrically and psychiatrically referred girls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:966-975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Arnold L: Sex differences in ADHD: conference summary. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1996; 24:555-569Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Gaub M, Carlson CL: Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1036-1045Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sharp W, Walter J, Marsh W, Ritchie G, Hamburger S, Castellanos X: ADHD in girls: clinical comparability of a research sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:40-47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Benjamin J, Krifcher B, Moore C, Sprich-Buckminster S, Ugaglia K, Jellinek MS, Steingard R, Spencer T, Norman D, Kolodny R, Kraus I, Perrin J, Keller MB, Tsuang MT: Further evidence for family-genetic risk factors in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: patterns of comorbidity in probands and relatives in psychiatrically and pediatrically referred samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:728-738Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wechsler D: Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Revised. New York, Psychological Corp, 1974Google Scholar

7. Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E), 4th revision. Fort Lauderdale, Fla, Nova University, Center for Psychological Studies, 1987Google Scholar

8. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP, Version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

9. John K, Gammon GD, Prusoff BA, Warner V: The Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA): testing of a new semistructured interview. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:898-911Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hollingshead AB: Four-Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, Department of Sociology, 1975Google Scholar

11. Moos R: Family Environment Scale, in The Ninth Mental Health Measurements Yearbook, vol 1. Edited by Mitchell JV. Lincoln, University of Nebraska, Buros Institute of Mental Measurements, 1985, pp 573-575Google Scholar

12. Rutter M: Studies of Psychosocial Risk: The Power of Longitudinal Data. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1988Google Scholar

13. Herjanic B, Reich W: Development of a structured psychiatric interview for children: agreement between child and parent on individual symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1982; 10:307-324Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Orvaschel H: Psychiatric interviews suitable for use in research with children and adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull 1985; 21:737-745Medline, Google Scholar

15. Sattler J: Psychological Assessment. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1988Google Scholar

16. Jastak S, Wilkinson GS: The Wide Range Achievement Test, Revised. Wilmington, Del, Jastak Associates, 1985Google Scholar

17. Assistance to States for Education for Handicapped Children: Procedures for Evaluating Specific Learning Disabilities: Federal Register. Bethesda, Md, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1977Google Scholar

18. Reynolds CR: Critical measurement issues in learning disabilities. J Spec Educ 1984; 18:451-476Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Krifcher Lehman B, Keenan K, Norman D, Seidman LJ, Kolodny R, Kraus I, Perrin J, Chen WJ: Evidence for the independent familial transmission of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning disabilities: results from a family genetic study. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:891-895Link, Google Scholar

20. Faraone S, Biederman J, Friedman D: Validity of DSM-IV subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a family study perspective. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:300-307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Spencer T, Faraone SV: Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder reduces risk for substance use disorder. Pediatrics 1999; 104:e20Google Scholar

22. Biederman J, Wilens TE, Mick E, Faraone SV, Weber W, Curtis S, Thornell A, Pfister K, Garcia Jetton J, Soriano J: Is ADHD a risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorders? findings from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:21-29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:565-576Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Houghton S, Douglas G, West J, Whiting K, Wall M, Langsford S, Powell L, Carroll A: Differential patterns of executive function in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder according to gender and subtype. J Child Neurol 1999; 14:801-805Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Arcia E, Conners CK: Gender differences in ADHD? J Dev Behav Pediatr 1998; 19:77-83Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8-19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Angold A, Costello J, Erkanli A: Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999; 40:57-87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Wittchen H, Reed V, Kessler R: The relationship of agoraphobia and panic in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:1017-1024Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Milberger S: How reliable are maternal reports of their children’s psychopathology? one year recall of psychiatric diagnoses of ADHD children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1001-1008Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT: Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull 1987; 101:213-232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Weber W, Russell RL, Rater M, Park K: Correspondence between DSM-III-R and DSM-IV attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1682-1687Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar