A Longitudinal and Retrospective Study of PTSD Among Older Prisoners of War

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the longitudinal changes in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom levels and prevalence rates over a 4-year time period among American former prisoners of war (POWs) from World War II and the Korean War. Retrospective symptom reports by World War II POWs dating back to shortly after repatriation were examined for 1) additional evidence of changing PTSD symptom levels and 2) evidence of PTSD cases with a long-delayed onset. METHOD: PTSD prevalence rates and symptom levels were measured by the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. For the longitudinal portion of the study, participants were 177 community-dwelling World War II and Korean POWs. For the retrospective portion, participants were 244 community-dwelling World War II POWs. RESULTS: PTSD prevalence rates and symptom levels increased significantly over the 4-year measurement interval. Retrospective symptom reports indicated that symptoms were highest shortly after the war, declined for several decades, and increased within the past two decades. Long-delayed onset of PTSD symptoms was rare. Demographic and psychosocial variables were used to characterize participants whose symptoms increased over 4 years and differentiate participants who reported a long-delayed symptom onset. CONCLUSIONS: Both longitudinal and retrospective data support a PTSD symptom pattern of immediate onset and gradual decline, followed by increasing PTSD symptom levels among older survivors of remote trauma.

Increasing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) levels among aging war veterans and Holocaust survivors have been reported (1–6). Long-delayed PTSD onset also has been noted (1, 7–12). These phenomena run counter to evidence that PTSD symptom levels decline following trauma (13–16). Whereas delayed onset is a subtype of PTSD, and up to 10% of PTSD cases have a latency of months to several years (14, 17), the notion that onset can occur decades after a trauma is debatable. Elucidation of these issues is critical to understanding the long-term effects of trauma.

These issues also have clinical relevance. An estimated 20%–25% of older American men have experienced combat (18–20). Rates of PTSD among Vietnam War veterans are likely to remain substantial as they age (21). Epidemiological studies indicate that the experience of a trauma that meets diagnostic criteria for PTSD is common, affecting 50%–70% of the U.S. population over a lifetime (13, 19, 22). In the coming years, clinicians and researchers will be called upon to respond to the needs of a growing cohort of older survivors of remote trauma.

Most longitudinal studies of PTSD have limited applicability to understanding older survivors of remote trauma because study samples were relatively young, the time periods covered relatively short, or the trauma relatively recent. An obvious avenue for studying the long-term course of PTSD is to examine cohorts of survivors who have lived with trauma for a half-century or more: survivors of World War II, the Holocaust, and the Korean War. Unfortunately, because the effects of trauma were not well understood, information about PTSD symptoms in the years and decades immediately following these events is minimal. The PTSD and aging literature therefore consists primarily of case studies and retrospective reports of symptom history.

Since the early 1980s, at least 11 case reports have appeared detailing symptom increases and long-delayed PTSD onset among Holocaust survivors and soldiers from World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. Four reports described symptom increases following a more recent trauma or stressor (23–26), and six described long-delayed PTSD onset in previously asymptomatic individuals (7, 8, 10–12, 23). Such reports focus attention on older trauma survivors but do not represent conclusive evidence of increasing symptoms or a pattern of long-delayed symptom onset. PTSD symptoms can fluctuate over time, and “new cases” may be those for whom symptom levels happened to be increasing when they were observed. Greater awareness about the effects of trauma may also have affected rates of symptom assessment and reporting, constituting long-delayed recognition, not long-delayed onset.

A study in which 442 American World War II prisoners of war (POWs) were asked to retrospectively report PTSD symptom severity during specific time periods, beginning with release from captivity, found no evidence of recent symptom increases (27). From release in 1945 to 1950, 60% reported being “seriously troubled” by PTSD symptoms. This rate decreased to 49% for the period 1950 to 1980 and remained essentially unchanged at 48% from 1980 to 1983. However, important symptom fluctuations may have been obscured by the collapse of so many years into single time periods.

Long-delayed PTSD onset has also been studied by using retrospective symptom reports. Among 147 World War II Dutch resistance fighters, 34% reported experiencing symptoms for the first time after 1970 (9). However, symptom reports may have been influenced because respondents were seeking compensation. In other samples of older veterans, long-delayed onset cases were rare (20, 28).

In the only reported longitudinal study of psychiatric morbidity in a cohort of older survivors of remote trauma (29), 208 Australian former POWs and non-POWs of World War II were examined in 1982–1983 and again by a different examiner 9 years later. A general decrease in psychiatric morbidity was reported, including a 50% decrease in anxiety disorders. PTSD was assessed only at the second examination. Unfortunately, interrater agreement was not assessed. The interviewers likely differed significantly in their diagnostic sensitivities, given the reported differences in axis I comorbidities (45% at the first interview versus 28% at the second).

The present study used contemporaneously gathered longitudinal data and retrospectively gathered symptom reports to obtain a more complete picture of changing PTSD symptom levels among older survivors of remote trauma. Moreover, the cohort examined was community dwelling and non-compensation-seeking. POWs from World War II and the Korean War are an especially valuable population for examining the long-term course of PTSD because their traumatic histories are remote, well documented, relatively uniform, and severe. In addition, older POWs have been extensively studied, validity studies of the major PTSD instruments are available (30), and lifetime and current PTSD prevalence rates have been documented. Approximately three-fourths of older POWs report having experienced clinically diagnosable levels of PTSD at some point since their release, and approximately half this rate have met criteria for current PTSD according to modern assessment methods (27, 31–33).

The present study had three primary hypotheses. First, for the longitudinal portion of the study, PTSD prevalence and symptom levels were reassessed in a cohort of community-dwelling POWs from World War II and the Korean War who were first assessed 4 years earlier (34). On the basis of clinical case reports, it was expected that PTSD prevalence rates and symptom levels would have significantly increased. Demographic and psychosocial variables were used to characterize participants whose symptoms increased by the second interview, although no hypotheses were made regarding these analyses.

Second, for the retrospective portion of the study, symptom level reports were requested in 5–10-year increments from repatriation up to the time of the first data collection (early 1990s) in a group of 244 community-dwelling POWs from World War II. The retrospective symptom reports were expected to demonstrate an increase in symptoms occurring since the 1980s (as per clinical reports) but not to levels experienced in the decades immediately following repatriation.

Finally, these retrospective symptom level reports from World War II POWs were coded into seven symptom courses (on the basis of typical symptom courses found in the literature), and the percentage reporting long-delayed onset was examined. It was predicted that fewer than 10% of individuals would report a first onset of symptoms during or after 1970. Demographic and psychosocial variables were used to characterize participants reporting a long-delayed symptom onset, although no hypotheses were made regarding these analyses.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were sought by using the roster of all known World War II and Korean War POWs in the catchment area of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center. At the first assessment, 262 male POWs from World War II (N=247) and the Korean War (N=15) participated, and 177 (165 World War II and 12 Korean) participated in both assessments. (At each assessment, the proportions within each study group that participated in the two conflicts were comparable to national estimates [35]). For the second assessment, questionnaires were mailed to the first assessment participants not known to have died (N=231). For eleven of these, relatives reported death or incapacitating illness (e.g., coma). In total, 177 usable questionnaires were returned, representing 80% of the 220 potential respondents and 68% of the first assessment participants. Average length of time between assessments was 50 months (SD=8.10, range=33–68). After complete description of the study to the participants, written informed consent was obtained.

Average time spent as a POW was 16 months (range=1–46) for participants at both assessment points. Additional demographic variables are available only for the second assessment participants. The average age was 75.5 years (SD=3.8, range=65–86). Average education was 13 years (SD=2.8).Most were retired (97%, N=171), and the mean number of months since retirement was 160 (SD=68.3, range=3–420). Thirty-nine percent (N=69) had a yearly household income of more than $25,000, 56% (N=99) made $10,000–$25,000, and 5% (N=9) made less than $10,000. Most were married (79%, N=140), with 10% (N=18) divorced, 10% (N=18) widowed, and 1% (N=1) never married. The majority of subjects were Caucasian (96%, N=170), with 4% (N=7) Native American.

Measures

PTSD was assessed with the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (36), which has been shown to have high internal consistency (0.94), test-retest reliability (0.97), sensitivity (0.93), and specificity (0.89) in clinical samples (36). A diagnostic cutoff score of 91 was used, which has been shown upon cross-validation to have good sensitivity (0.66) and specificity (0.87) (kappa=0.50) against SCID-based PTSD diagnoses in a group of community-dwelling World War II POWs (37). Internal consistency was high in this study at both the first and second assessments (alpha=0.93 and 0.94, respectively).

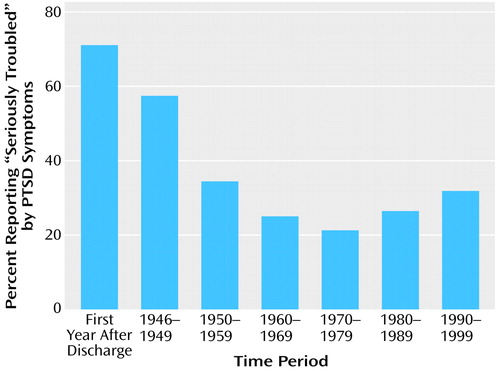

Following administration of the PTSD measure at the first assessment, World War II POW respondents were asked to check the time periods (first year after discharge, 1946–1949, 1950–1959, 1960–1969, 1970–1979, 1980–1989, and 1990 to the present) when they were “seriously troubled” by PTSD symptoms. A total of 244 of the 247 World War II respondents provided the retrospective data. For the current study, these responses were coded into seven PTSD symptom course categories (Table 1 provides category descriptions).

At the first assessment, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Version Modified for the Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (SCID PTSD) (38) and the SCID Non-Patient Edition (39) were administered to examine two variables: lifetime incidence of alcohol abuse or dependence (1=yes, 2=no; 37% [N=96] responded yes) and the lifetime number of axis I disorders other than PTSD (mean=0.2, range=0–3). Additional details about the administration of the SCID are provided elsewhere (34). Two variables were assessed by self-report: marital status (1=married, 2=divorced or not married; 88% [N=230] were married) and a rating of current health (1=excellent, 4=poor; mean=2.8, SD=0.7).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

A comparison of respondents and nonrespondents at the second assessment on age, educational level, months and theater of captivity, level of PTSD symptoms, and PTSD diagnosis was conducted. Continuous variables were analyzed by using t tests, and chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. Only age was significant, in that second assessment participants were younger (mean=75.5, SD=3.8) than nonparticipants (mean=77.1, SD=4.5) (t=2.98, df=260, p<0.01).

Longitudinal Change in PTSD Prevalence Rates and Symptom Levels

At the first assessment, 47 subjects (27%) met or exceeded the Mississippi scale cutoff score, whereas 60 subjects (34%) met or exceeded the cutoff at the second assessment. At the second assessment there were 19 new cases, six no longer meeting criteria, 41 who met criteria at both measurements, and 111 who did not meet criteria at either measurement. A McNemar’s change test with correction for continuity found this was a significant increase in the number of cases of PTSD (χ2=6.76, df=4, p<0.05).

To better characterize new cases of PTSD, the psychosocial variables, Mississippi scale scores, and select demographic variables were compared by t tests and chi-square tests for the 19 new PTSD subjects and the 111 subjects who did not meet criteria at either time period. New PTSD subjects were found to have significantly less education (mean=11.4, SD=2.3) than those whose status did not change (mean=13.6, SD=2.5) (t=–3.57, df=127, p<0.001), poorer self-reported health (mean=3.00 [SD=0.58] versus 2.58 [SD=0.60]) (t=2.81, df=122, p<0.006), and a higher rate of lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence (42% [N=8] versus 20% [N=22] (χ2=4.54, df=1, p<0.05). New PTSD subjects also had significantly higher Mississippi scale scores at the first assessment (mean=80.16, SD=6.18) than those whose status did not change (mean=65.76, SD=11.80) (t=5.19, df=128, p<0.0001). No differences were found for length of imprisonment, number of lifetime axis I diagnoses, theater of imprisonment, or marital status.

A paired samples t test performed to examine changes in PTSD symptom levels between the two assessment points showed that levels at the second assessment were significantly higher (mean=81.0, SD=21.6, range=37–145) than those of the first (mean=77.5, SD=20.0, range=42–142) (t=3.91, df=176, p<0.001). Differences in demographic and psychosocial variables between veterans whose Mississippi scale score increased (N=106) and those whose score decreased or stayed the same (N=71) were not significant.

Retrospective Reports of PTSD Symptom Levels Since Discharge

Figure 1 shows the percentage of World War II POW respondents who indicated that they felt “seriously troubled” by PTSD symptoms during specific time periods. The overall pattern indicates early difficulties for the majority of respondents, a fairly rapid decline for many thereafter, followed by a slower decline that continued until the sixth time period (approximately 40 years after discharge). Beginning in 1980, a gradual increase is seen, although levels remain below those of the immediate postwar years.

Table 1 shows the number of World War II respondents in each PTSD symptom course category and each group’s percent of the total. Most respondent’s responses fit into a particular category, thus the “fluctuating” or miscellaneous category was small (7%). The largest group consisted of individuals reporting that they had experienced symptoms beginning shortly after the war but who felt that they had recovered by 1949 (29%) or no later than 1969 (17%). The next largest group consisted of individuals who felt that they had been seriously troubled by symptoms continuously since the war (18%). The “long-delayed onset” group, consisting of individuals reporting no symptoms before the fifth time period, is noteworthy in that there were so few respondents (2%) reporting this symptom pattern. The “reactivation” group, on the other hand, was larger (11%). Finally, 16% reported never having been “seriously troubled” by PTSD symptoms since discharge.

A closer examination of the long-delayed symptom onset category revealed that this group of respondents had, on average, the lowest education, the shortest length of imprisonment, and the worst self-reported health status of any of the seven symptom course groups. Finally, their mean Mississippi scale score at the first assessment (when their retrospective symptom histories were provided) was 80.67, or below the cutoff criteria. Only two of the six long-delayed onset respondents met Mississippi scale criteria for current PTSD.

Discussion

According to a recognized and validated measure, PTSD prevalence and symptom levels were found to have increased modestly but significantly over approximately 4 years in a group of community-dwelling older survivors of remote trauma. PTSD symptom levels assessed with the Mississippi scale at the two assessment points were within the range of values found in previous studies of nonpsychiatric combat and former POW veterans of World War II and Korea (40). The findings support the supposition that PTSD severity may increase in older trauma survivors. This contradicts the notion that PTSD is stable overall in its chronic form (41) or that it uniformly decreases in severity over time. There are, to our knowledge, no other longitudinal studies of older survivors of remote trauma in which PTSD was examined at two points in time. As the first study of its kind, replication of these results, as well as studies examining older survivors of differing kinds of remote trauma, are needed.

We found that new PTSD subjects reported more health problems than those whose symptoms remained below criteria at both time periods, consistent with findings that self-reported health is partially mediated by increases in PTSD following trauma exposure (42). This may also reflect an overlap between the constructs of PTSD and health complaints or a response bias. New PTSD subjects also had less education, suggesting that educational level represents a protective factor. Lower pretrauma intelligence increased the risk for developing PTSD symptoms in a sample of Vietnam veterans, even after adjusting for extent of combat exposure (43). New PTSD subjects also had higher lifetime rates of alcohol abuse/dependence, consistent with findings that alcohol abuse/dependence is associated with PTSD in the general population and that alcohol dependence often predates PTSD onset (22).

Retrospective reports of feeling “seriously troubled” by PTSD symptoms since repatriation revealed symptom increases in the preceding two decades. Symptom levels were high immediately following and for a few years after repatriation. Symptoms then began a slow decline lasting into the 1970s, when approximately one-fifth felt “seriously troubled.” Beginning in the 1980s and continuing into the early 1990s, more respondents began to feel “seriously troubled” by PTSD symptoms. That the retrospective reports are in agreement with the longitudinal data further supports the supposition that symptom increases have occurred and are continuing to occur. The retrospective reports also concur with the appearance, beginning in the early 1980s, of numerous case studies describing increasing PTSD among older survivors of remote trauma.

An important developmental milestone that would have occurred in the 1980s for World War II veterans, and one that might have contributed to PTSD symptom increases, is retirement. The idea that retirement has had an effect on PTSD symptom levels in this cohort of older trauma survivors has been noted in case reports and descriptions of therapy groups for older combat veterans (3, 4). Furthermore, a retrospective chart review of World War II veterans referred for a PTSD evaluation found that retirement was the most common event noted around the time of referral (44). Because the vast majority of the current respondents were many years past retirement, the immediate effects of retirement could not be assessed in this study.

Finally, the retrospective symptom level reports of the World War II POWs at the first assessment indicated that long-delayed PTSD onset is rare. The fact that only two of the six men who indicated this symptom pattern met Mississippi scale criteria at the time they reported their symptom levels casts further doubt on the phenomenon; some of these cases may represent reporting errors on the part of participants. Such a low level of long-delayed onset is consistent with other studies of older veteran samples (28, 33) but is markedly lower than the findings of the only other study to assess evidence of long-delayed onset with detailed time-sampled retrospective symptom reports (9). However, the cohort assessed in that study was nonveteran and compensation seeking. Nevertheless, more research is needed to verify the current findings regarding the frequency of long-delayed onset and other symptom course patterns in older survivors of remote trauma.

A difficulty inherent in this and related studies is determining the accuracy of retrospective accounts of PTSD symptom levels. In the current study, respondents’ perceptions of their level of symptom difficulties was in surprisingly good agreement with available data. The finding that just over two-thirds reported difficulties shortly after release is in agreement with lifetime PTSD prevalence rates in older POW samples (27, 45). Symptom decreases in the years after a trauma are in agreement with longitudinal studies of PTSD (14). Finally, 76% of the respondents accurately characterized their symptoms in relation to their score on the Mississippi scale at the first assessment. Especially given the fact that no empirical data were collected contemporaneously on the PTSD symptom levels of this or any other trauma group in the decades following World War II, the data presented here, while based on self-report, appear to be generally valid.

Because this was a community cohort, results may be broadly generalizable to elderly individuals with trauma histories. However, limits to generalizability may arise because the group was predominantly white, all male, and experienced war trauma. Studies of PTSD in younger subjects have found a higher percentage of African Americans reporting delayed onset of symptoms compared to Caucasians (14). Higher PTSD prevalence rates and differences in the types of traumas that precede PTSD have been found for women than for men (14, 22). Ethnicity and race have been found to be risk factors for exposure to war stress and development of PTSD (46). Thus, symptom courses and their proportions may differ across trauma survivor populations. The extent and duration of the physical and psychological threat endured by these POWs is, thankfully, unusual. Percentages of individuals with chronic PTSD are expected to be less for survivors of less traumatic stressors, and the symptom courses also might differ.

These results highlight the importance of assessing trauma histories in older patients. PTSD may be undetected or misdiagnosed in World War II veterans, even in those seeking medical or psychiatric treatment (47). Many older individuals may never have been previously identified as suffering from trauma-related symptoms or themselves made the connection between current distress and remote trauma. Clinical reports suggest that events such as death or illness of a loved one often precede referral for PTSD evaluations among older trauma survivors (44). Clinicians need to be sensitive to the possibility that patients with trauma histories may be at risk for a reemergence or intensification of PTSD symptoms as they move through their later years. Conversely, older survivors of remote trauma who have so far not experienced significant PTSD symptoms may be reassured that they are not likely to experience a long-delayed onset.

More information is needed about the long-term course of PTSD. Studies tracking PTSD symptom levels over a lifespan would extend our knowledge about PTSD generally and the interplay of trauma exposure and aging specifically. Such studies also could explore the impact of developmental milestones, including retirement, on PTSD symptoms. The Vietnam veteran cohort is of an age in which such research could be fruitful.

|

Received Jan. 21, 2000; revision received Dec. 6, 2000; accepted Feb. 21, 2001. From the Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis; and the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Minneapolis. Address reprint requests to Dr. Port, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 660 W. Redwood St., Suite 200, Baltimore, MD 21201-1596. Supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and a Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship from the University of Minnesota.

Figure 1. Percentage of Community-Dwelling World War II POWs (N=244) Who Reported Being “Seriously Troubled” by PTSD Symptoms for Each Time Period Since Discharge

1. Clipp EC, Elder GH: The aging veteran of World War II: psychiatric and life course insights, in Aging and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Edited by Ruskin PE, Talbott JA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996, pp 19-51Google Scholar

2. Kahana B: Late-life adaptation in the aftermath of extreme stress, in Stress and Health Among the Elderly. Edited by Wykle ML, Kahana E, Kowal J. New York, Springer, 1992, pp 151-171Google Scholar

3. Lipton MI, Schaffer WR: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the older veteran. Mil Med 1986; 151:522-524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Nichols BL, Czirr R: Post-traumatic stress disorder: hidden syndrome in elders. Clin Gerontol 1986; 5:417-433Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Sleek S: Older vets just now feeling pain of war. Am Psychol Assoc Monitor, May 1998, p 1Google Scholar

6. Steinitz LY: Psycho-social effects of the Holocaust on aging survivors and their families. J Gerontological Social Work 1982; 4:145-152Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Hamilton JW: Unusual long-term sequelae of a traumatic war experience. Bull Menninger Clin 1982; 46:539-541Medline, Google Scholar

8. Herrmann N, Eryavec G: Delayed onset post-traumatic stress disorder in World War II veterans. Can J Psychiatry 1994; 39:439-441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Op den Velde W, Falger PRJ, Hovens JE, de Groen JHM, Lasschuit LJ, Van Duijn H, Schouten EGW: Posttraumatic stress disorder in Dutch resistance veterans from World War II, in International Handbook of Traumatic Stress Syndromes. Edited by Wilson JP, Raphael B. New York, Plenum, 1993, pp 219-230Google Scholar

10. Pomerantz AS: Delayed onset of PTSD: delayed recognition or latent disorder? (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1609Medline, Google Scholar

11. Richmond JS, Beck JC: Posttraumatic stress disorder in a World War II veteran (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1485-1486Google Scholar

12. Van Dyke C, Zilberg NJ, McKinnon JA: Posttraumatic stress disorder: a thirty-year delay in a World War II veteran. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1070-1073Google Scholar

13. Green BL: Psychosocial research in traumatic stress: an update. J Trauma Stress 1994; 7:341-362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Green BL, Lindy JD, Grace MC, Gleser GC, Leonard AC, Korol M, Winget C: Buffalo Creek survivors in the second decade: stability of stress symptoms. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1990; 60:43-54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Phifer JF, Kaniasty KZ, Norris FH: The impact of natural disaster on the health of older adults: a multiwave prospective study. J Health Soc Behav 1988; 29:65-78Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Zlotnick C, Warshaw M, Shea MT, Allsworth J, Pearlstein T, Keller MB: Chronicity in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and predictors of course of comorbid PTSD in patients with anxiety disorders. J Trauma Stress 1999; 12:89-100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Solomon Z: Immediate and long-term effects of traumatic combat stress among Israeli veterans of the Lebanon War, in International Handbook of Traumatic Stress Syndromes. Edited by Wilson JP, Raphael B. New York, Plenum, 1993, pp 321-332Google Scholar

18. Molinari V, Williams W: An analysis of aging World War II POWs with PTSD: implications for practice and research. J Geriatr Psychiatry 1995; 28:99-114Google Scholar

19. Norris FH: Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:409-418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Spiro A, Schnurr PP, Aldwin CM: Combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in older men. Psychol Aging 1994; 9:17-26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Lyons JA, McClendon OB: Changes in PTSD symptomatology as a function of aging. NOVA PSI Newsletter, Aug 1990, pp 13-18Google Scholar

22. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048-1060Google Scholar

23. Aarts PGH, Op Den Velde W: Prior traumatization and the process of aging: theory and clinical implications, in Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. Edited by Van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L. New York, Guilford, 1996, pp 359-377Google Scholar

24. Christenson RM, Walker JI, Ross DR, Maltbie AA: Reactivation of traumatic conflicts. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:984-985Link, Google Scholar

25. Hamilton J, Workman RH Jr: Persistence of combat-related posttraumatic stress symptoms for 75 years. J Trauma Stress 1998; 11:763-768Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Pary R, Turns D, Tobias CR: A case of delayed recognition of posttraumatic stress disorder (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:941Link, Google Scholar

27. Zeiss RA, Dickman HR: PTSD 40 years later: incidence and person-situation correlates in former POWs. J Clin Psychol 1989; 45:80-87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lee KA, Vaillant GE, Torrey WC, Elder GH: A 50-year prospective study of the psychological sequelae of World War II combat. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:516-522Link, Google Scholar

29. Tennant C, Fairley MJ, Dent OF, Sulway MR, Broe A: Declining prevalence of psychiatric disorder in older former prisoners of war. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:686-689Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Page WF: The Health of Former Prisoners of War: Results From the Medical Examination Survey of Former POWs of World War II and the Korean Conflict. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1992Google Scholar

31. Eberly RE, Engdahl BE: Prevalence of somatic and psychiatric disorders among former prisoners of war. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:807-813Abstract, Google Scholar

32. Goldstein G, van Kammen W, Shelly C, Miller DJ, van Kammen DP: Survivors of imprisonment in the Pacific theater during World War II. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1210-1213Google Scholar

33. Kluznik JC, Speed N, Van Valkenburg C, Magraw R: Forty-year follow-up of United States prisoners of war. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1443-1446Google Scholar

34. Engdahl B, Dikel TN, Eberly R, Blank A Jr: Posttraumatic stress disorder in a community group of former prisoners of war: a normative response to severe trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1576-1581Google Scholar

35. Stenger CA: American Prisoners of War in WWI, WWII, Korea, Vietnam, Persian Gulf, and Somalia. Washington, DC, Veterans Health Services and Research Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs Advisory Committee on Former Prisoners of War, 2000Google Scholar

36. Keane TM, Caddell JM, Taylor KL: Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: three studies in reliability and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:85-90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Engdahl BE, Eberly RE, Blake JD: Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder in World War II veterans. Psychol Assess 1996; 8:445-449Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Spitzer RL, Williams JB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Version Modified for the Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, April 1, 1987Google Scholar

39. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP, Version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

40. Blake DD, Keane TM, Wine PR, Mora C, Taylor KL, Lyons JA: Prevalence of PTSD symptoms in combat veterans seeking medical treatment. J Trauma Stress 1990; 3:15-27Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Horowitz M: Stress Response Syndromes, 2nd ed. Northvale, NJ, Jason Aronson, 1992Google Scholar

42. Wolfe J, Schnurr PP, Brown PJ, Furey J: Posttraumatic stress disorder and war zone exposure as correlates of perceived health in female Vietnam War veterans. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994, 62:1235-1240Google Scholar

43. Macklin ML, Metzge LJ, Litz BT, McNally RJ, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Lower precombat intelligence is a risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998, 66:323-326Google Scholar

44. Kaup BA, Ruskin PE, Nyman G: Significant life events and PTSD in elderly World War II veterans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1994; 2:239-243Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Sutker PB, Allain AN, Winstead DK: Psychopathology and psychiatric diagnoses of World War II Pacific theater prisoners of war survivors and combat veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:240-245Link, Google Scholar

46. Friedman MJ, Ashcraft ML, Beals JL, Keane TM, Manson SM, Marsella AJ: Final Report: Matsunaga Vietnam Veterans Project, vol 1. West Haven, Conn, National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and National Center for American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 1997Google Scholar

47. Rosen J, Fields RB, Hand AM, Falsettie B, Van Kammen DP: Concurrent posttraumatic stress disorder in psychogeriatric patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1989; 2:65-69Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar