Does the Manic/Mixed Episode Distinction in Bipolar Disorder Patients Run True Over Time?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors sought to determine whether the manic/mixed episode distinction in patients with bipolar disorder runs true over time. METHOD: Over an 11-year period, the observed distribution of manic and mixed episodes (N=1,224) for patients with three or more entries in the management information system of a community mental health center (N=241) was compared to the expected distribution determined by averaging 1,000 randomly generated simulations. RESULTS: Episodes were consistent (all manic or all mixed) in significantly more patients than would be expected by chance. CONCLUSIONS: These data suggest a pattern of diagnostic stability over time for manic and mixed episodes in patients with bipolar disorder. Careful prospective studies of this issue are needed.

In DSM-IV, manic and mixed episodes in bipolar disorder patients are distinguished on the basis of cross-sectional psychopathology. Some evidence supports that these episode subtypes can be distinguished on the basis of differential treatment response as well. For episodes of classic mania, two randomized studies have suggested greater efficacy of lithium over divalproex (1, 2), while the same databases have suggested greater efficacy of divalproex over lithium for mixed episodes (2, 3). The present study addresses the possibility that these episode types maintain diagnostic stability over time.

Method

We obtained from the management information system of our community mental health center data for all inpatients or outpatients with bipolar I disorder who had diagnostic entries of 296.4x (manic or hypomanic episode), 296.5x (bipolar depressed episode), or 296.6x (mixed episode) between August 1, 1989, and August 1, 1999. Diagnostic entries were of three types: hospital admission, hospital discharge, or reevaluation. Hospital diagnoses were made by psychiatrists and psychiatric residents. Reevaluation diagnoses were made by primary outpatient clinicians who were mostly psychologists, nurses, and social workers. Duplicate entries and admission diagnoses were omitted. We omitted admission diagnoses because they are likely to reflect the same episode as discharge diagnoses but are generated from less information.

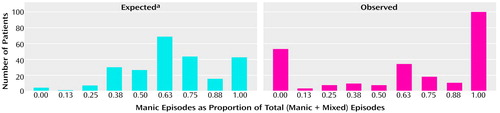

To evaluate whether patients experienced manic/mixed episodes consistently over time, we first computed the manic episode proportion for each individual. This proportion (number of manic episodes divided by the number of total [manic plus mixed] episodes) could range from 0 (no manic episodes) to 1 (no mixed episodes). For the principal analysis we required that each patient have at least three episodes (which gave us 1,224 episodes from 241 patients). From these data, we generated the observed distribution of the manic episode proportions for the 241 patients (Figure 1). Next we used a randomization test (4) to investigate the expected distribution of manic episode proportions. We randomly assigned manic or mixed episodes to the 241 patients with the assumption that the probability of an episode being manic or mixed was independent of whether other episodes for the same individual were manic or mixed. Since 67% (N=823 of 1,224) of the episodes for all individuals were manic, we fixed the overall probability of a manic episode at 0.67 and the overall probability of a mixed episode at 0.33. The number of episodes assigned to each patient was required to be identical to the observed distribution. This randomization was then repeated 999 times. The 1,000 distributions were then ranked by the total number of consistent cases: those having manic but no mixed episodes (manic episode proportion=1) plus those having mixed but no manic episodes (manic episode proportion=0). For purposes of visual comparison to the observed distribution, the 1,000 random distributions were averaged to illustrate the expected distribution.

We also conducted multiple additional randomization analyses in which the required total number of episodes was at least one (2,102 episodes from 886 patients), two (1,617 episodes from 416 patients), four (968 episodes from 158 patients), and five (671 episodes from 91 patients) as well as including or excluding various patient and diagnosis entry types.

As a supplementary analysis, we divided subjects in the principal data set (N=241) into groups whose initial episode was manic or mixed and then calculated the manic episode proportion for subsequent episodes for each subject. Then we used univariate regression to determine if initial episode predicted subsequent manic episode proportion.

Results

The average number of consistent cases (all manic or all mixed episodes) for the 1,000 random distributions was 47 (20% of patients). The highest number of consistent cases in a random distribution was 68 (28%). As seen in Figure 1, the observed distribution contained 153 consistent cases (100 in which all episodes were manic, 53 in which all were mixed). This consistency rate (63%) was significantly higher than would be expected to occur by chance (randomization p<0.001). This significant difference remained when we compared the observed consistency rate with that of the highest rate of the 1,000 randomizations for patients with one (83% versus 69%, respectively), two (67% versus 38%), four (60% versus 25%), and five (64% versus 36%) episodes (randomization p<0.001 for all). Analyses substituting admission diagnoses for discharge diagnoses or excluding reevaluation diagnoses were similarly significant.

The 100 patients with at least three manic but no mixed entries had a mean of 0.35 depressed entries (SD=0.89). The 53 patients with at least three mixed but no manic entries had a mean of 0.41 depressed entries (SD=0.91).

The supplementary analysis excluded 14 of the 241 patients with three or more entries whose first entry in the management information system was for a depressed episode. For the 148 patients whose initial episode was manic (mean manic episode proportion=0.82, SD=0.27), 63% (N=93) were consistently manic or depressed over time. For the 79 patients whose initial episode was mixed (mean manic episode proportion=0.25, SD=0.39), 65% (N=51) were consistently mixed or depressed. Initial episode (mean manic or mixed) was significantly associated with subsequent manic episode proportion (r=0.65, df=225, p<0.001).

Discussion

These data suggest that the manic/mixed episode distinction in patients with bipolar disorder may run true over time. Manic and mixed episodes were associated to a similar degree with pure depressive episodes. Our findings are generally consistent with those from two previous retrospective studies (5, 6).

Several limitations must be noted. Most importantly we cannot equate a diagnostic entry in the management information system with identification of illness episodes. First, diagnostic entries in the management information system were dependent on the clinical diagnostic process, which undoubtedly was inaccurate to some degree in our database as with clinical administrative databases in general. In addition, there may have been considerable drift in how clinicians recognized mixed episodes over the 11 years covered by the data set. Second, there are problems both with sensitivity and specificity of the management information system entries of the clinical diagnoses. Sensitivity problems arise because diagnoses are not always changed in the management information system when there is an episode subtype change. For example, this methodologic problem is presumably the reason for the low rate of depressive entries observed, rather than our cohort being very atypical in terms of unipolar mania. Patients may have had depressed episodes treated as outpatients, but reevaluation entries may not have been submitted. Clinicians may not have been able to observe depressed episodes because the patient was out of treatment, or they may have overlooked subclinical episodes. Specificity problems could arise if reevaluation entries were made for reasons other than episode subtype change (e.g., a change of clinician or a patient’s return to treatment after a temporary absence). Hospital discharge entries are likely less prone to this specificity problem than are reevaluation entries, however, and the significant findings in the analysis restricted to discharge entries are reassuring. Third, each succeeding diagnostic entry is unlikely to reflect an independent diagnostic effort but presumably was influenced by knowledge of previous clinical diagnoses.

Although the majority of patients had either manic but no mixed entries or mixed but no manic entries, a substantial minority (37%) had both manic and mixed entries. These 37% are not necessarily inconsistent with episode subtypes running true over time. Some of these patients may actually have had only manic or only mixed illness episodes, with episode misidentification being related to imprecision in the clinical diagnostic process as discussed earlier. Moreover, even if it were established in future studies that bipolar disorder with manic and depressed episodes and bipolar disorder with mixed and depressed episodes were distinct syndromes, observation of some patients with both manic and mixed episodes would be expected due to comorbidity between distinct syndromes.

Despite the important methodologic limitations, these data taken together with previous results suggest that within bipolar disorder patients, manic and mixed episode subtypes may each run true over time. If confirmed in future careful prospective studies, the manic episode versus mixed episode distinction may then usefully inform genetic and genetic epidemiology studies of bipolar disorder. The current data also strengthen the need to investigate treatment outcome separately in patients with episodes of classic mania and those with mixed episodes.

Received Feb. 25, 2000; revisions received Oct. 17, 2000, and Jan. 24, 2001; accepted Feb. 22, 2001. From the Connecticut Mental Health Center. Address reprint requests to Dr. Woods, Treatment Research Program, Department of Psychiatry, Connecticut Mental Health Center, Yale University School of Medicine, 34 Park St., New Haven, CT 06519; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-54446.

Figure 1. Expected and Observed Distributions of Manic Episode Proportions of 241 Bipolar Disorder Patients With at Least Three Manic or Mixed Episodes Over an 11-Year Period

aRepresents the mean of 1,000 distributions in which manic or mixed episodes were randomly assigned to the 241 patients. The number of episodes assigned to each patient was the same as in the observed distribution. The probability of each episode being either manic or mixed was assumed to be independent of whether other episodes within the same individual were manic or mixed. Episode probability was set at 0.67 for manic episodes and 0.33 for mixed episodes.

1. Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris DD: Reply to SW Woods: Classic mania: treatment response to divalproex or lithium (letter). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:1050Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Freeman TW, Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, Lesem MD, Swann AC: A double-blind comparison of valproate and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:108-111Link, Google Scholar

3. Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris D, Calabrese JR, Petty F, Small J, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM: Depression during mania: treatment response to lithium or divalproex. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:37-42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Noreen EW: Computer Intensive Methods for Testing Hypotheses. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989Google Scholar

5. Dell’Osso L, Placidi GF, Nassi R, Freer P, Cassano GB, Akiskal HS: The manic-depressive mixed state: familial, temperamental and psychopathologic characteristics in 108 female inpatients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 240:234-239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Keck PE Jr, Tugrul KL, West SA, Lonczak HS: Differences and similarities in mixed and pure mania. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:187-194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar