Hazardous Benzodiazepine Regimens in the Elderly: Effects of Half-Life, Dosage, and Duration on Risk of Hip Fracture

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: While benzodiazepine treatment is known to increase the risk of hip fracture in older populations, controversy persists over which characteristics of benzodiazepine use (e.g., elimination half-life, dosage, duration of use) are most associated with such risks. METHOD: The authors reviewed the health care utilization data of 1,222 hip fracture patients and 4,888 comparison patients frequency matched on the basis of age and gender (all were at least 65 years old). Patients were enrolled in Medicare as well as in the New Jersey Medicaid or Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled programs. Benzodiazepine use, as well as other covariates, were assessed before the index date (which was either the date of hospital admission for hip fracture surgical repair or, for the comparison subjects, a randomly assigned, frequency-matched date). RESULTS: All benzodiazepine doses ≥3 mg/day in diazepam equivalents significantly increased the adjusted risk of hip fracture by 50%. Significantly increased adjusted risks of hip fracture were seen during the initial 2 weeks of use (60% increase) and after more than 1 month of continuous use (80% increase) but not for 2–4 weeks of continuous use. Use of benzodiazepines other than long-acting agents significantly increased the risk of hip fracture by 50%. CONCLUSIONS: Even at modest doses, including some low doses currently advocated in prescribing guidelines for older patients, treatment with benzodiazepines appears to increase the risk of hip fracture. Patients appear to be particularly vulnerable immediately after initiating therapy and after more than 1 month of continuous use. Benzodiazepines with shorter half-lives appear to be no safer than longer half-life agents. Clinicians should be aware of these risks and weigh them against potential benefits when prescribing for elderly patients.

It has been estimated that elderly patients consume 50% of all benzodiazepine prescriptions, despite making up less than 13% of the population (1). This intensity of use has raised concerns, since benzodiazepines have been implicated as a cause of numerous adverse drug events, including dependency, withdrawal, rebound symptoms, daytime sedation, confusion, cognitive deficits, ataxia, dysarthria, diplopia, vertigo, falls, and hip fractures (2–20). In spite of these risks, some benzodiazepine use by elderly patients is clinically useful. For this reason, it is critically important to identify particularly hazardous regimens that should be avoided as well as more benign regimens that could be used preferentially when a benzodiazepine is required.

Previous studies of benzodiazepine regimens that may be associated with risk of adverse events have produced conflicting results. Early investigations of benzodiazepines with different elimination half-lives have suggested that long-acting benzodiazepines are more likely to cause adverse events than short-acting agents (4–6, 13–16). However, other studies have found significantly greater risks of adverse effects with use of short-acting agents (10, 12, 17).

Some investigators have proposed that benzodiazepine dosage may be a more important determinant of whether a regimen is hazardous than elimination half-life (12). Prior studies have reported higher risks for depression, poisonings, suicides, motor vehicle accidents, falls, and hip fractures with use of high doses (8, 9, 12, 15, 18). Unfortunately, many previous studies have been limited by lack of dose standardization, examination of only a narrow dose range, or use of excessively high thresholds to define high doses (e.g., ≥20 mg/day in diazepam equivalents) (19). Quantification of the risks associated with the complete range of benzodiazepine dosages, particularly more modest dose levels, is still needed.

The risks associated with duration of use have also come under some scrutiny. Previous studies have shown that prolonged continuous benzodiazepine use is associated with problems such as loss of efficacy, habituation, and increasing severity of cognitive deficits (20, 21). Unfortunately, previous investigations have examined only limited duration ranges or used excessively long periods to define prolonged duration of use (e.g., ≥1 year) (12, 20). Greater clarification is needed of the risks associated with the complete spectrum of durations, particularly shorter periods of continuous use.

The current study had three specific aims, each designed to shed light on characteristics of benzodiazepine use that increase the risk for hip fracture, a particularly serious adverse drug event for elderly patients. First, we sought to compare long-acting benzodiazepines to agents with shorter elimination half-lives in terms of their risks for hip fracture. Second, we attempted to quantify the risks associated with a variety of benzodiazepine dosages, including the relatively low dose levels currently recommended for older adults but which may still pose hazards. Third, we examined the risks associated with continuous benzodiazepine use over a wide range of treatment durations. Such information is crucial for enabling clinicians to reduce use of the most hazardous regimens while ideally leaving intact safe and indicated use of this important class of medications.

Method

Data Sources

We extracted information on all individuals enrolled in the New Jersey Medicaid program from January 1, 1993, to June 30, 1995. Available information included demographic characteristics and dates of enrollment; hospitalization, outpatient, and nursing home utilization data (including admission and discharge dates, physician encounters, diagnoses, and procedures); and data for all filled prescriptions (including medication, quantity dispensed, and days supply). The New Jersey Medicaid program has no deductibles and no maximum benefit and charges no copayment for prescription medications. The indigent status of Medicaid enrollees results in essentially no out-of-pocket (i.e., out-of-system) health care utilization.

Additional information on nonindigent elderly was derived from the New Jersey Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled program for the same time period. Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled is a state-specific program of reimbursement for the drug expenses of nonindigent elderly and disabled citizens, the vast majority of whom are age 65 or older. During the study period, the Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled program had the highest income ceiling of any such program nationally, producing a recipient population that was both large and further from extreme poverty.

Medicare data used in the present study included data on hospitalizations and nursing home stays from Part A and data on outpatient professional services and procedures from Part B for essentially all New Jersey residents over age 65.

We identified all Medicare beneficiaries who were also enrolled in either Medicaid or the Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled program, since these programs, but not Medicare, provide comprehensive data on all prescription drug use. All traceable person-specific identifiers were transformed into anonymous coded study numbers to protect the privacy of program participants. Data on each subject were assembled on a person-specific basis into a relational database by using Sybase software to integrate information on all filled prescriptions, procedures, physician encounters, hospitalizations, and long-term care for each individual.

Study Population

The study population consisted of all subjects who were age 65 and older on July 1, 1993. Hip fracture patients were defined as any subject hospitalized from January 1, 1994, to December 31, 1994, who underwent surgical repair of a hip fracture, as reflected in a claim for this procedure by a surgeon (22, 23). The index date for these patients was considered to be the date of their hospital admission for surgery. For individuals who had more than one hospitalization for hip fracture repair, only the first event was considered. Four comparison patients were drawn at random from the study population and were frequency matched to each of the hip fracture patients by year of birth and gender. Each comparison patient was then randomly assigned an index date, with such dates frequency matched to the index dates of the hip fracture patients. Comparison patients were required to have no history of hip fracture or evidence of hip fracture surgical repair on or before their index date. Any patient hospitalized in the month before their index date was excluded.

To ensure that subjects were eligible for medical service benefits during a 1-year period, each subject was required to have filed at least one claim for a nonprescription service from January 1, 1994, to December 31, 1994. In addition, to ensure that subjects had been eligible for prescription benefits during a 24-month study period (January 1, 1993, to December 31, 1994), each subject was required to have filled at least one prescription for any medication through the Medicaid or Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled programs during each of four consecutive 6-month periods beginning January 1, 1993. These requirements also ensured that each subject had a uniform 6-month period of eligibility before the index date during which covariates could be assessed.

Benzodiazepine Exposure Variables

Use

Prescription data (quantity dispensed and days supply) were used to identify all days subjects had a filled prescription for orally administered forms of alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, estazolam, flurazepam, halazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, prazepam, quazepam, temazepam, or triazolam. Because of occasional intermittent use, the days supply was multiplied by 1.5 to ensure ascertainment of use beyond the stated end date of a given prescription. Subjects were considered to have been exposed to benzodiazepines if their index date was covered by any benzodiazepine prescription.

Half-life

Orally administered forms of diazepam, flurazepam, chlordiazepoxide, and clonazepam were considered long-acting agents and were compared to all other benzodiazepines with shorter elimination half-lives. The recorded quantity dispensed and days supply were used to identify all days that subjects had a filled prescription for a specific agent, and exposure was defined as the index date being covered by the prescription.

Dosage

Daily dose levels were recorded for all benzodiazepine prescriptions that covered index dates. Doses were expressed in milligrams of diazepam equivalents (24). The distribution of doses among those exposed on the index date was divided into four approximately equal-sized groups (quartiles): >0–2.9, 3–5.9, 6–8.9, and ≥9 mg/day.

Duration

Days supply data (not multiplied by a factor of 1.5) for all orally administered benzodiazepine prescriptions during the 120 days up to and including the index date were used as an estimate of days of continuous benzodiazepine use. Continuous use was defined as having no interruption of 15 days or more. The distribution of continuous treatment durations among those exposed to benzodiazepines was divided into four approximately equal-sized groups (quartiles): 1–14, 15–28, 29–42, and ≥43 days.

Other Covariates

Program enrollment information was used to determine age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status (lower socioeconomic status defined as being enrolled in Medicaid, higher socioeconomic status defined as being enrolled in the Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled program).

All filled prescriptions in the 180 days before the index date were reviewed to record patient exposure to any antipsychotic medications, antidepressants, other psychoactive medications (including barbiturates, nonbenzodiazepine sedatives and anxiolytics, stimulants, and lithium), estrogen replacement therapy, oral corticosteroids, or thiazide diuretics.

Clinical and health care utilization in the 6 months before the index date was also assessed for all patients. We used ICD-9 diagnostic information from all inpatient and outpatient claims to calculate a modified Charlson Comorbidity Index score (25). Variables reflecting the type and intensity of health services used in the 6 months before the index date were constructed, including the total number of medications (generic entities) used, number of days spent hospitalized, number of days spent in a nursing home, and number of outpatient physician visits.

Analyses

Initially, we calculated the crude odds ratios for hip fracture among those exposed to particular benzodiazepine regimens. To identify the independent risks of exposure to benzodiazepines while controlling for other patient variables of interest, we then constructed a multivariate unconditional logistic regression model of the risk of hip fracture by using the logistic procedure of SAS (26). Variables representing age (continuous), gender, estrogen replacement therapy, and exposure to benzodiazepines on the index date were first introduced into the model. All remaining covariates were subjected to a forward, step-wise selection procedure with a selection criterion of p≤0.20. Adjusted odds ratios were estimated from this final model, and the statistical significance of relationships was assessed by using Wald chi-square statistics and two-sided p values. We also used adjusted odds ratios from the final model and the prevalence of use of psychotropic medications in the comparison group to calculate the percentage of hip fractures in an elderly population that could be attributed to benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and other psychoactive medications.

To determine the independent risks associated with use of long-acting agents versus all other benzodiazepines with shorter elimination half-lives, we substituted variables representing these two exposures into the final model. We then identified the independent risks of exposure to different benzodiazepine dose levels by substituting variables representing each benzodiazepine dose quartile on the index date into the final model. We also determined the independent risks of different treatment durations by substituting variables representing each quartile of continuous benzodiazepine use before the index date into the final model. In sensitivity analyses, we examined the independent risks of alternative categorizations of benzodiazepine dose level and continuous duration. Finally, we identified the independent effects of benzodiazepine half-life, dose, and duration of use in models that were adjusted for one other benzodiazepine characteristic (i.e., we constructed three multivariate models into which two benzodiazepine exposure variables were simultaneously added: 1) agent half-life plus dose, 2) agent half-life plus treatment duration, and 3) dose plus treatment duration).

Results

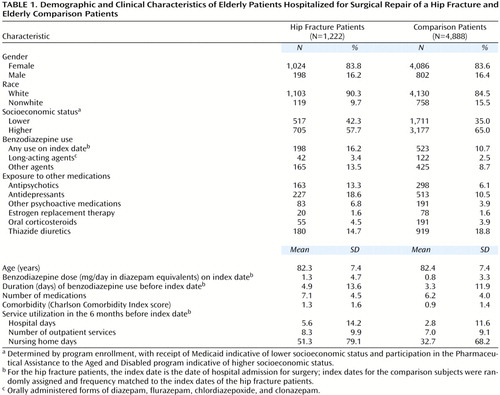

Characteristics of the study population appear in Table 1. The mean age was 82, and most subjects were women. The vast majority of subjects were white, more so among the hip fracture than the comparison patients. More hip fracture than comparison patients were from the lower socioeconomic class (represented by enrollment in Medicaid); conversely, fewer hip fracture than comparison patients were from a somewhat higher class (represented by enrollment in the Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled program).

A greater proportion of hip fracture than comparison patients were exposed to benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, other psychoactive medications, and oral corticosteroids before their index date. A comparable proportion of hip fracture and comparison patients used estrogen replacement therapy, and fewer hip fracture than comparison patients used thiazide diuretics. Hip fracture patients were observed to consume a greater total number of medications than comparison patients in the 6 months before the index date. Hip fracture patients had more comorbid illness than did comparison patients. The utilization of medical care in the 6 months before the index date was also higher among hip fracture than among comparison patients.

The crude and adjusted odds ratios for potential risk factors of hip fracture appear in Table 2. Exposure to benzodiazepines on the index date was significantly associated with risk of hip fracture. After adjustment for the effects of demographic and clinical variables, health care utilization, and the other medications shown, exposure to benzodiazepines on the index date continued to be significantly associated with an increased independent risk of hip fracture. Other medication classes for which significantly higher independent risks were found after adjustment for the effects of demographic and clinical variables, health care utilization, and the other medications shown included antipsychotics, antidepressants, and other psychoactive medications. We found no statistically significant differences when we directly compared the adjusted odds ratio for benzodiazepines to the adjusted odds ratios for antipsychotics (χ2=0.19, df=1, p=0.66), antidepressants (χ2<0.01, df=1, p=0.99), or other psychoactive medications (χ2=0.28, df=1, p=0.60). On the basis of the prevalence of use in the comparison group, we estimated that the percentage of hip fractures attributable to benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and other psychoactive medications in an elderly population would be 4.8%, 3.5%, 4.6%, and 1.5%, respectively.

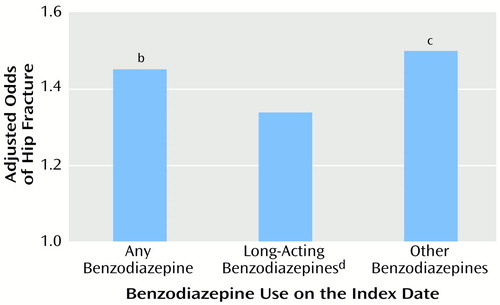

Figure 1. presents a comparison of the adjusted risks of hip fracture for use of long-acting agents on the index date versus benzodiazepines with shorter elimination half-lives. The risk of hip fracture was not significantly higher for use of long-acting agents but use of agents other than long-acting benzodiazepines significantly increased the adjusted risk by 50% over subjects not exposed to benzodiazepines at all on the index date.

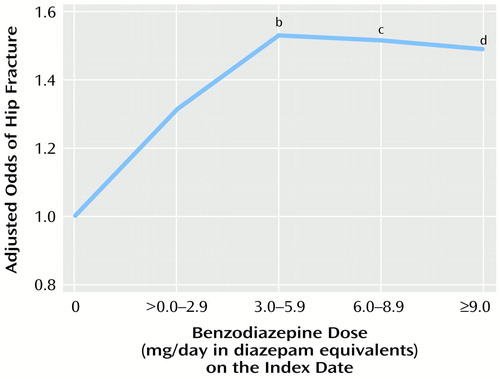

Figure 2. presents the adjusted risks of hip fracture associated with use of different benzodiazepine doses on the index date. The risk of hip fracture was not significantly higher for use of less than 3 mg/day in diazepam equivalents. However, all benzodiazepine doses ≥3 mg/day in diazepam equivalents significantly increased the adjusted risk of hip fracture by at least 50%. These results remained essentially unchanged when alternative categorizations of benzodiazepine dosage were employed in sensitivity analyses.

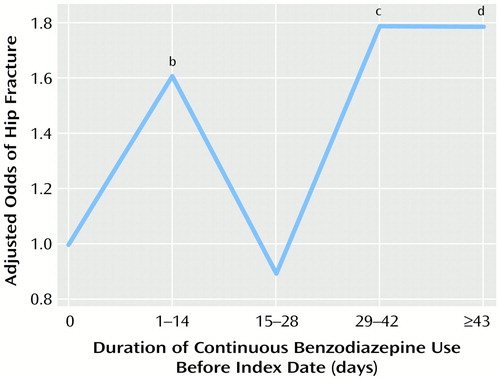

Figure 3. presents the adjusted risks of hip fracture associated with various durations of benzodiazepine treatment before the index date. The risk of hip fracture was significantly higher (60% increase in risk) when the benzodiazepine treatment had been newly initiated (continuous duration of 1–14 days). For continuous use of 15–28 days, the risk of hip fracture was not significantly higher, but longer-term use (>28 days) was again associated with greater risks of hip fracture (80% increase in risk). When alternative categorizations of continuous duration were employed in sensitivity analyses, these results did not change substantially. We did not find evidence for an interaction between duration of use and benzodiazepine half-life (model with main effect plus interaction terms compared to a model containing main effect terms only, likelihood ratio χ2=0.01, df=5, p>0.90).

The odds ratios associated with half-life variables, dose quartiles, or duration quartiles did not change substantially in our models that were controlled for one additional benzodiazepine characteristic (results not shown), suggesting that our findings for each drug parameter (i.e., half-life, dose, and duration) were not confounded by the others.

Discussion

In this study of 1,222 elderly subjects with hip fracture and 4,888 comparison patients, we observed significantly higher risks of hip fracture with use of benzodiazepines at even modest dose levels. Even some low-dose regimens considered relatively safe in older patients were found to have risks comparable in magnitude to those conferred by larger doses. Likely mechanisms through which even small increases in benzodiazepine dosage may increase the risk of hip fracture include the dose-dependent increases in daytime sedation, confusion, cognitive deficits, ataxia, diplopia, vertigo, and falls that have been observed by other investigators (2–6, 11). Although high benzodiazepine dose levels have been observed previously to be a risk factor for adverse events, most prior studies have reported thresholds higher than the 3–5.9 mg/day in diazepam equivalents observed in this study (12, 15, 16). The dose range of 3–5.9 mg/day in diazepam equivalents for which we found significantly higher risks of hip fracture includes the dose level (5 mg/day) currently advocated for the elderly in prescribing guidelines for older patients (24, 27).

We also observed significantly higher risks of hip fracture during initial treatment (i.e., the first 14 days) as well as with long-term use (after 28 days). One study that examined the risks of motor vehicle accidents associated with various durations of continuous benzodiazepine treatment also found significantly higher risks at initiation (after 1 to 7 days) and with extended use (after 61–365 days) but not for intermediate durations of use (8–60 days) (14). In our study, significantly higher risks of hip fracture were seen during the initial 2 weeks but not during the subsequent 2 weeks of use. Previous research that has shown that after 2 weeks of continuous use, but generally not before, benzodiazepine users develop tolerance and habituation to the psychomotor effects of these agents (21, 28, 29). Mechanisms that could explain our finding of higher risk of hip fracture with prolonged duration (after 1 month of continuous use) include the accumulation of active metabolites as well as the greater severity of cognitive and motor deficits observed with greater chronicity of use in prior research (20, 30, 31).

Finally, we identified significantly higher risks of hip fracture with use of benzodiazepines with shorter elimination half-lives. These agents may be associated with the development of greater cognitive impairments such as memory deficits, more rapid tolerance, or more severe withdrawal symptoms than those experienced with long-acting agents (32–35). On the other hand, it is important to consider other explanations for these results, especially in the context of earlier findings that have often (8, 9, 13–16) but not always (10–12, 36) identified greater risks for the long-acting agents rather than their counterparts with shorter half-lives. Earlier reports that alerted clinicians to potential risks of hip fracture with long-acting agents may have caused prescribers to avoid such agents in patients at higher risk for falls.

Our findings concerning other risk factors for hip fracture are consistent with previous reports (8, 13, 17, 37–42) and provide evidence for the validity of our analyses and ability of our models to detect true hazards. Nevertheless, our results should be interpreted in light of the following four sets of potential limitations. First, the associations observed in this study could have occurred by chance, especially because multiple comparisons were made. A related issue in a study with a large sample size is that the risks identified may be statistically significant but not of clinical or public health importance. To help put the hazards associated with benzodiazepines into perspective, we calculated that 4.8% of hip fractures occurring in an elderly population can be attributed to benzodiazepine use. Furthermore, the percentage of hip fractures attributable to benzodiazepine use appears to be at least as great as the percentages attributable to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and other psychoactive medications (3.5%, 4.6%, and 1.5%, respectively).

Second is the possibility of confounding by the indications for benzodiazepine use. Such confounding would arise if certain benzodiazepine regimens (i.e., use of shorter half-life agents, higher doses, or very short or very long treatment durations) had been preferentially prescribed to patients with conditions such as severe anxiety, agitation, insomnia, dementia, or alcohol withdrawal. If so, these indications may have placed elderly patients at higher risk of hip fracture rather than their benzodiazepine regimens. We did adjust our analyses for measures of chronic illness such as days spent in the hospital or nursing home, number of physician visits, Charlson comorbidity score, and other medications taken. In spite of such control, it is still possible that residual confounding by indication may have remained.

Third, some features of our study design may have limited the generalizability of our results. For example, requiring eligible subjects to have made claims for medications and nondrug services may have caused them to be more frail than noneligible subjects. However, other features may have helped enhance the external validity of our results. Unlike highly selected participants in clinical trials, our subjects were drawn from a large and diverse general population of elderly that included poor, nonpoor, community-dwelling, and nursing home residents. In addition, we were able to examine the safety of benzodiazepine use representative of the agents, dosages, durations, and conditions of usual practice rather than under the highly controlled circumstances of clinical trials.

In spite of these potential limitations, results from this study have important clinical implications. First, these results suggest that it is prudent for clinicians and patients to exercise caution with all benzodiazepines and not be falsely reassured that choosing agents with particular half-lives, without regard to other important features such as dosage and duration of use, will protect patients from potential adverse effects. However, these cautions should not be interpreted to mean that the safest course of action is to always avoid use of benzodiazepines in older patients. Instead, after carefully appraising the risks associated with specific benzodiazepine regimens, clinicians should weigh these risks against the often substantial hazards of not treating the underlying indication (e.g., anxiety symptoms, agitation, or insomnia). Finally, results of the study suggest that clinicians should not simply substitute other psychotropics for benzodiazepines, since antipsychotics, antidepressants, and other psychoactive medications all appear to confer comparable risks for hip fracture in elderly patients.

|

|

Received July 19, 2000; revision received Dec. 5, 2000; accepted Jan. 6, 2001. From the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics and the Departments of Medicine and Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Address reprint requests to Dr. Wang, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 221 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a research grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-10014).

Figure 1. Relation of Hip Fracture Risk to Benzodiazepine Use on the Index Date for Elderly Patients Hospitalized for Surgical Repair of a Hip Fracture and Elderly Comparison Patientsa

aFor the hip fracture patients, the index date is the date of hospital admission for hip fracture surgery; index dates for the comparison patients were randomly assigned and frequency matched to the index dates of the hip fracture patients. Adjusted odds ratios were derived from multivariate logistic regression analyses with the risk factors depicted in Table 2 as covariates.

bSignificantly higher than rate for subjects with no benzodiazepine use (Wald χ2=16.4, df=1, p=0.001).

cSignificantly higher than rate for subjects with no benzodiazepine use (Wald χ2=15.4, df=1, p=0.001).

dOrally administered forms of diazepam, flurazepam, chlordiazepoxide, and clonazepam.

Figure 2. Relation of Hip Fracture Risk to Benzodiazepine Dose Level on the Index Date for Elderly Patients Hospitalized for Surgical Repair of a Hip Fracture and Elderly Comparison Patientsa

aFor the hip fracture patients, the index date is the date of hospital admission for hip fracture surgery; index dates for the comparison patients were randomly assigned and frequency matched to the index dates of the hip fracture patients. Adjusted odds ratios were derived from multivariate logistic regression analyses with the risk factors depicted in Table 2 as covariates.

bSignificantly higher than rate for subjects with no benzodiazepine use (Wald χ2=7.3, df=1, p<0.007).

cSignificantly higher than rate for subjects with no benzodiazepine use (Wald χ2=5.3, df=1, p<0.03).

dSignificantly higher than rate for subjects with no benzodiazepine use (Wald χ2=4.8, df=1, p<0.03).

Figure 3. Relation of Hip Fracture Risk to Duration of Continuous Benzodiazepine Use Before the Index Date for Elderly Patients Hospitalized for Surgical Repair of a Hip Fracture and Elderly Comparison Patientsa

aFor the hip fracture patients, the index date is the date of hospital admission for hip fracture surgery; index dates for the comparison patients were randomly assigned and frequency matched to the index dates of the hip fracture patients. Adjusted odds ratios were derived from multivariate logistic regression analyses with the risk factors depicted in Table 2 as covariates.

bSignificantly higher than rate for subjects with no benzodiazepine use (Wald χ2=7.4, df=1, p<0.007).

cSignificantly higher than rate for subjects with no benzodiazepine use (Wald χ2=12.7, df=1, p=0.0004).

dSignificantly higher than rate for subjects with no benzodiazepine use (Wald χ2=10.5, df=1, p<0.002).

1. Wysowski DK, Baum C: Outpatient use of prescription sedative-hypnotic drugs in the United States, 1970 through 1989. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151:1779–1783Google Scholar

2. Benzodiazepine Dependence, Toxicity, and Abuse: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC, APA, 1990Google Scholar

3. Swift CG: Postural instability as a measure of sedative drug response. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1984; 18:87S–90SCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program: clinical depression of the central nervous system due to diazepam and chlordiazepoxide in relation to cigarette smoking and age. N Engl J Med 1973; 288:277–280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Greenblatt DJ, Allen MD, Shader RI: Toxicity of high dose flurazepam in the elderly. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1977; 21:355–361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Roth T, Hartse K, Saab P, Piccione P, Kramer M: The effects of flurazepam, lorazepam, and triazolam on sleep and memory. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1980; 70:231–237Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Whitcup SM, Miller F: Unrecognized drug dependence in psychiatrically hospitalized elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987; 35:297–301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ray WA, Griffin MR, Schaffner W, Baugh DK, Melton LJ III: Psychotropic drug use and the risk of hip fracture. N Engl J Med 1987; 316:363–369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ray WA, Griffin MR, Downey W: Benzodiazepines of long and short elimination half-life and the risk of hip fracture. JAMA 1989; 262:3303–3307Google Scholar

10. Cumming RG, Klineberg RJ: Psychotropics, thiazide diuretics and hip fractures in the elderly. Med J Aust 1993; 158:414–417Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Sorock GS, Shimkin EE: Benzodiazepine sedatives and the risk of falling in a community-dwelling elderly cohort. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:2441–2444Google Scholar

12. Herings RC, Stricker BH, de Boer A, Bakker A, Sturmans A: Benzodiazepines and the risk of hip falling leading to femur fractures. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:1801–1807Google Scholar

13. Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, Cauley J, Black D, Vogt TM: Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:767–773Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Hemmelgarn B, Suissa S, Huang A, Boivin JF, Pinard G: Benzodiazepine use and the risk of motor vehicle crash in the elderly. JAMA 1997; 278:27–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Ray WA, Fought RL, Decker MD: Psychoactive drugs and the risk of injurious motor vehicle crashes in elderly drivers. Am J Epidemiol 1992; 136:873–883Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Marcantonio ER, Juarez G, Goldman L, Mangione CM, Ludwig LE, Lind L, Katz N, Cook EF, Orav EJ, Lee T: The relationship of post-operative delirium with psychoactive medications. JAMA 1994; 272:1518–1522Google Scholar

17. Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME: Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis, I: psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:30–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Neutel CI, Downey W, Senft D: Medical events after a prescription for a benzodiazepine. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 1995; 4:63–73Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Thomson M, Smith WA: Prescribing benzodiazepines for noninstitutionalized elderly. Can Fam Physician 1995; 41:792–798Medline, Google Scholar

20. Golombok S, Moodley P, Lader M: Cognitive impairment in long-term benzodiazepine users. Psychol Med 1988; 18:365–374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Erman MK: Insomnia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1987; 10:525–539Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modifications, vol 1, Diseases: Tabular List: Commission on Professional and Hospital Activities. Ann Arbor, Mich, Edwards Brothers, 1986Google Scholar

23. Physicians’ Current Procedural Terminology, 4th ed. Chicago, American Medical Association, 1989Google Scholar

24. Salzman C (ed): Clinical Geriatric Psychopharmacology, 3rd ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1998Google Scholar

25. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45:613–619Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. SAS, version 6.12. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1996Google Scholar

27. Sadavoy J, Lazarus LW, Jarvik LF, Grossberg GT (eds): Comprehensive Review of Geriatric Psychiatry, 2nd ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996Google Scholar

28. Curran HV: Tranquilising memories: a review of the effects of benzodiazepines on human memory. Biol Psychiatry 1986; 23:179–213Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Ghoneim MM, Mewaldt SP: Benzodiazepines and human memory. Biol Psychiatry 1990; 23:179–213Google Scholar

30. Gottlieb GL, Kumar A: Conventional pharmacologic treatment for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1993; 43:S56–S63Google Scholar

31. Rummans TA, Davis LJ, Morse RM, Ivnik RJ: Learning and memory impairment in older, detoxified, benzodiazepine-dependent patients. Mayo Clin Proc 1993; 68:731–737Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Scharf MB, Fletcher K, Graham JP: Comparative amnestic effects of benzodiazepine hypnotic agents. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49:134–137Medline, Google Scholar

33. Roehrs T, Merlotti L, Zorick F, Roth T: Sedative, memory, and performance effects of hypnotics. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994; 116:130–134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Hallfors DD, Saxe L: The dependence potential of short half-life benzodiazepines: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 1993; 83:1300–1304Google Scholar

35. Nagy A: Long-term treatment with benzodiazepines: theoretical, ideological, and practical aspects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1987; 335:47–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Lichtenstein MJ, Griffin MR, Cornell JE, Malcolm E, Ray W: Risk factors for hip fracture occurring in the hospital. Am J Epidemiol 1994; 140:830–838Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Thapa PB, Gideon P, Cost TW, Milam AB, Ray WA: Antidepressants and the risk of falls among nursing home residents. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:875–882Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Silverman SL, Madison RE: Decreased incidence of hip fracture in Hispanics, Asians, and Blacks: California hospital discharge data. Am J Public Health 1988; 78:1482–1483Google Scholar

39. Gregg EW, Cauley JA, Seeley DG, Ensrud KE, Bauer DC: Physical activity and osteoporotic fracture risk in older women. Ann Intern Med 1998; 129:81–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. LaCroix AZ, Wienpahl J, White LR, Wallace RB, Scherr PA, George LK, Cornoni-Huntley J, Ostfeld AM: Thiazide diuretic agents and the incidence of hip fracture. N Engl J Med 1990; 322:286–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Felson DT, Sloutskis D, Anderson JJ, Anthony JM, Kiel DP: Thiazide diuretics and the risk of hip fracture: results from the Framingham Study. JAMA 1991; 265:370–373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. LaCroix AZ, Ott SM, Ichikawa L, Scholes D, Barlow WE: Low-dose hydrochlorothiazide and preservation of bone mineral density in older adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133:516–526Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar