Impact of Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder in Managed Care

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors determined the costs associated with generalized social anxiety disorder in a managed care setting. METHOD: A three-phase mail and telephone survey was conducted from July to October 1998 in two outpatient clinics of a large health maintenance organization (HMO). The survey assessed direct costs, indirect costs, health-related quality of life, and clinical severity associated with generalized social anxiety disorder, both alone and with comorbid psychopathology. RESULTS: The weighted prevalence rate of current generalized social anxiety disorder was 8.2%. In the past year, only 0.5% of subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder had been accurately diagnosed. Yet 44.1% had a mental health specialty visit or had been prescribed an antidepressant, and psychiatric comorbidity was found in 43.6%. Noncomorbid generalized social anxiety disorder was associated with significantly lower health-related quality of life, work productivity, and earnings and greater utilization of health services; generalized social anxiety disorder with comorbid psychopathology was even more disabling. Suicide was attempted by 21.9% of subjects with noncomorbid generalized social anxiety disorder. Persons with average-severity generalized social anxiety disorder had probabilities of graduating from college that were 10 percentage points lower, earned wages that were 10% lower, and had probabilities of holding a technical, professional, or managerial job that were 14 percentage points lower than the comparison group. CONCLUSIONS: In a community cohort of HMO members, generalized social anxiety disorder was rarely diagnosed or treated despite being highly prevalent and associated with significant direct and indirect costs, comorbid depression, and impairment.

The prevalence and debilitating nature of social anxiety disorder—also known as social phobia—is increasingly being recognized (1). Generalized social anxiety disorder, which is the most severe and disabling form, is associated with significant impairment in educational, occupational, and social functioning (1–3). Most people with social anxiety disorder have the more severe generalized form (4). According to results from the National Comorbidity Survey (5), the 12-month prevalence rate of social anxiety disorder, which included both the generalized and nongeneralized subtypes, was 7.9%, with a lifetime prevalence of 13.3%. Social anxiety disorder is also prevalent in primary care, with a lifetime prevalence of 14.4% (6). The direct costs of social anxiety disorder have not been studied in a managed care population.

The findings of well-controlled studies have only recently demonstrated that social anxiety disorder is associated with serious clinical and societal consequences. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (3) found social anxiety disorder to be associated with high rates of outpatient medical treatment, suicidality, financial dependency, and psychiatric comorbidity. Persons with social anxiety disorder have alcohol abuse rates that are higher than those seen in individuals with most other anxiety disorders (7, 8). Other studies have found persons with social anxiety disorder to be functionally impaired in the areas of education, employment, and social relationships (1–3, 8, 9) and to have poorer health-related quality of life (1, 3, 10).

Despite compelling epidemiological findings and strong evidence of effective pharmacological (11, 12) and psychotherapeutic (13) interventions, the perception that social anxiety disorder is a trivial condition persists. Given current concerns about the allocation of health care resources, establishing both the clinical and economic impact of social anxiety disorder is important to determine to what extent its costs warrant reimbursement.

It is difficult, however, for studies that use community or specialty clinic populations to measure patterns of diagnosis, treatment, and health care utilization for people with social anxiety disorder in a way that is generalizable to primary care or managed care populations. Community populations include persons who are uninsured or face other barriers to health care. Clinical trial populations are highly selected, usually exclude common comorbid conditions, and are often recruited by advertisement. These limitations can be overcome by focusing on an insured population (e.g., members of a managed care organization), in which access to visits, diagnostic codes, and prescription histories are available in automated claims databases. We examined the clinical and economic impact associated with generalized social anxiety disorder in a managed care population. Direct costs (e.g., medical expenditures), indirect costs (e.g., changes in wages and productivity), and intangible costs (e.g., health-related quality of life and the clinical burden of social anxiety disorder) were measured. We used several multivariate statistical techniques to compute the direct and indirect costs of generalized social anxiety disorder.

Method

Population

There are more than 180,000 enrollees in the Dean Health Plan, a large Midwestern health maintenance organization (HMO) in the United States. Study participants were selected from among the 30,000 enrollees belonging to one of two participating clinics. Participants were eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 64; did not have schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or a life-threatening illness; did not have point-of-service coverage; and had been continuously enrolled in the HMO for at least 1 year. A total of 10,724 eligible subjects were identified.

Study Design

The principal investigator sent to a random sample of 7,165 eligible subjects a questionnaire and an invitation to participate in a study about the effect of illness on health-related quality of life. The study was conducted from July to October 1998. The questionnaire consisted of the three-item short-form screener of the Social Phobia Inventory (14) and the three-item depression screener developed by Rost et al. (15) in conjunction with the Medical Outcomes Study.

Subjects were informed that they might be invited to participate in the next phase of the study on the basis of their answers to the survey and were asked to indicate if they were willing to be contacted. A follow-up mailing was sent to subjects who did not respond to the first mailing.

Subjects screening positive for social anxiety disorder and who agreed to participate were interviewed by telephone to confirm the diagnosis and administer the outcome measures. All interviewers received additional training in administering all diagnostic interviews and rating scales. Diagnostic proficiency and interrater reliability were demonstrated before initiating assessments. The interview consisted of the social phobia module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (16)— modified to assess generalized social anxiety disorder—and the major depressive episode, mania, panic disorder, alcohol and drug abuse, and suicide modules of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (17). The interview also consisted of the quality-of-life scale of the Short-Form General Health Survey (18), the Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale (2), and the Work Productivity and Impairment Inventory (19). Demographic and socioeconomic data were also collected (e.g., employment status, hours of work, earnings over the past year). All SCID and Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview diagnoses reflected current diagnoses.

Finally, subjects were asked if they were willing to participate in a second telephone interview, which consisted of computer-administered versions of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (20), 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (21), and the Sheehan Disability Scale (22). Subjects were paid $20 for participating in the second interview.

To evaluate the effects of social anxiety disorder, individuals with the disorder were compared with subjects without any of the aforementioned diagnoses. A random sample of 310 subjects who returned the questionnaire, screened negative for social anxiety disorder and depression, and consented to be contacted were chosen to be telephoned and screened. Data for each of these individuals were weighted to represent 3.97 subjects. Finally, to compare the effects of social anxiety disorder with those of pure (i.e., no comorbidity) major depression, 446 persons screening positive for depression (but not social anxiety disorder) and who consented to participate in the next phase of the study were recontacted by telephone to confirm the diagnosis and administer the outcome measures.

Primary and Secondary Comparisons

The primary comparison was between subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder (i.e., those with a SCID-confirmed diagnosis and no comorbidity as confirmed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview) (group A) and subjects with no psychopathology (confirmed by the SCID and Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview) (group D). These groups were chosen for the primary comparison in order to assess the effect of generalized social anxiety disorder apart from any comorbid diagnoses. Two secondary comparisons were also performed, the first of which involved the subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder and comorbid psychopathology (group B) and the subjects with no diagnosis (group D). The other secondary comparison was between subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder (group A) and subjects with pure major depression (group C). The latter comparison allowed for an evaluation of the effect of social anxiety disorder alone relative to the impact of major depression alone.

Outcome Measures

Direct costs

The primary outcome measure for direct costs was the number of ambulatory outpatient visits in the past year. The secondary outcome measure was the actual dollar amount spent on medical care for the 1-year time period ending 3 months before the screening call. These data were obtained from the HMO automated claims and pharmacy databases.

Indirect costs

The primary outcome measure for indirect costs was the total score on the Work Productivity and Impairment Inventory. Secondary outcome measures for indirect costs included hourly wages, hours of work, and employment controlling for age, gender, education, and occupation. Additional secondary outcome measures were educational attainment and occupational choice. Occupation was determined by using the International Standard Classification of Occupations (23).

Health-related quality of life

Primary outcome measures for health-related quality of life were the social functioning, role functioning (emotional), mental health index, and the standardized mental component items from the Short-Form General Health Survey. The Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale, Sheehan Disability Scale, and the remainder of the Short-Form General Health Survey items were secondary outcome measures.

Clinical severity

The primary measures of clinical severity for generalized social anxiety disorder and depression were the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and the 17-item Hamilton depression scale, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Direct costs

Analysis of the number of ambulatory outpatient visits was conducted by using a negative binomial regression (24). Control variables included age, age-squared, age-cubed, gender, and the age-by-gender interaction. Standard errors were calculated through a bootstrap method (25). Sampling weights (26) were used in all analyses (including those of indirect costs) when comparing groups that contained subjects who screened negative for both social anxiety disorder and depression.

Differences between total medical expenditures (medical and pharmacy) were analyzed by using a two-part model (27, 28). Independent variables included age, age-squared, age-cubed, gender, and the age-by-gender interaction.

Indirect costs

Hourly wages and hours of work were analyzed by using ordinary least square regression (24), while differences in employment, educational attainment, and occupational choice were analyzed by using probit models (24). The effects of generalized social anxiety disorder on these outcomes were measured by estimating the effect of clinical severity as determined by the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale.

In the analysis of the logarithm of hourly wages, the control variables included age, age-squared, education, gender, and occupation. Because generalized social anxiety disorder may likely influence an individual’s level of education and choice of occupation, both of which may indirectly affect wages, the results of a model that did not control for education and occupation were also reported. The two analyses should measure the direct effects of generalized social anxiety disorder on wages and provide an upper boundary for the “total” effect of generalized social anxiety disorder, respectively.

In the analysis of educational attainment, we estimated the probability of graduating from college. In the model of occupational choice, we estimated the probability of being in a professional, managerial, or technical occupation. The models included controls for age, age-squared, gender, parental education, and parental occupation.

In the analysis of the effect of generalized social anxiety disorder on the probability of employment and the number of hours worked, controls included age, education, gender, marital status, and the number of children in the family.

Clinical measures, health-related quality of life, work productivity

Between-group differences on clinical and health-related quality-of-life measures and total scores on the Work Productivity and Impairment Inventory scores were examined by using analysis of variance or analysis of covariance for continuous variables, adjusting for age and gender. Chi-square statistics were used for categorical variables. The study had a power of at least 0.80 to detect differences (with two-tailed tests at a p<0.05 significance level) for all primary outcome measures with the exception of number of outpatient visits, for which the power was 0.77.

Results

Subject Distribution

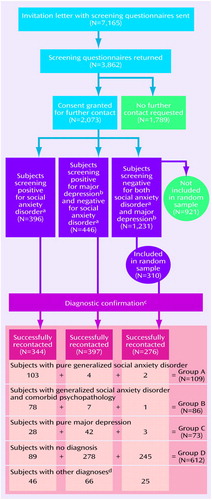

Of 7,165 letters sent, 3,862 (53.9%) were returned, and 2,073 subjects (53.7%) consented to be contacted (Figure 1). Of these, 396 screened positive for social anxiety disorder (included within this group were subjects with possible depression), 446 subjects screened positive for depression but negative for social anxiety disorder, and 1,231 subjects screened negative for both social anxiety disorder and depression.

A total of 1,017 subjects were successfully recontacted and assessed with the diagnostic interviews and outcome measures. Final subject diagnostic categories were determined by the diagnostic interviews (i.e., the SCID and Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview) and were as follows: generalized social anxiety disorder (N=195), pure major depression (without generalized social anxiety disorder, N=73), and no diagnosis (N=612).

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

The mean age of the 7,165 subjects to whom the questionnaires were sent was 41.7 years; 51.5% were female. The 3,862 subjects who returned the questionnaire were older (mean age=43.3 years) and more likely to be female (56.7%). Among the subjects for whom diagnoses were confirmed, the percentage of each group that was female did not significantly differ. Other demographic and disease severity characteristics of this population are summarized in Table 1. The weighted prevalence rate of generalized social anxiety disorder was 8.2%. Weighting was necessary, since 19.1% of those agreeing to be contacted screened positive for social anxiety disorder compared with 13.5% of subjects not agreeing to be contacted.

Among subjects with a confirmed diagnosis of generalized social anxiety disorder, only (0.5%) had a social anxiety disorder diagnosis in the HMO database in the year preceding the survey. Yet 31.4% had a mental health specialty visit, 34.3% had filled at least one antidepressant prescription, and 44.1% had either a mental health specialty visit or an antidepressant prescription. The mean Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale score for all subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder was 74 (68 for those with pure generalized social anxiety disorder and 82 for those with comorbid psychopathology). The mean age at onset of generalized social anxiety disorder was 12.49 years (SE=0.59). For subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder and comorbid depression, the mean age at onset of major depression was 24.34 years (SE=1.54), which was significantly younger than the age at onset of major depression for subjects with pure major depression (mean=32.48, SE=1.72; t=3.54, df=134, p=0.001).

Nearly half (43.6%) of the subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder had current psychiatric comorbidity, including depression (35.8%), alcohol abuse (11.3%), panic disorder (5.9%), and drug abuse (3.4%). Subjects were asked which came first, generalized social anxiety disorder or the comorbid diagnosis; 13.5% could not remember. Generalized social anxiety disorder occurred first (i.e., was the primary diagnosis) in the majority of subjects who remembered (71.4%). For the remaining subjects, the comorbid diagnosis either preceded generalized social anxiety disorder (14.3%) or was concurrent (14.3%).

Direct Costs

The annual direct costs of health care services utilization are presented in Table 2. Subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder made significantly more outpatient visits than those with no diagnosis but not more than subjects with pure major depression. Subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder and comorbid psychopathology also made significantly more clinic visits than those with no diagnosis. Similar findings were observed for total medical expenditures, but only the differences between generalized social anxiety disorder subjects with comorbid psychopathology and subjects with no diagnosis were statistically significant.

Indirect Costs

Wages, education, occupation, employment, and hours of work

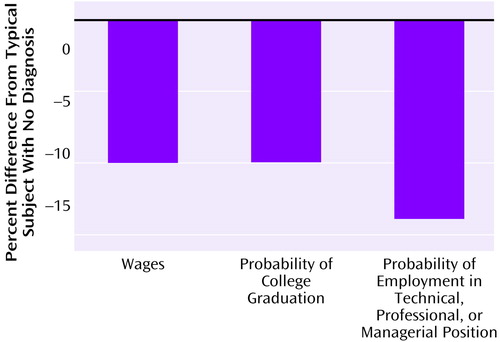

Analysis of wages indicated that severity of generalized social anxiety disorder (i.e., Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale score) was a strong and statistically significant predictor of hourly wages. The difference in mean scores on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale between subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder and those with no diagnosis (68 versus 27, respectively) indicates that generalized social anxiety disorder is associated with 10% lower wages (z=2.48, df=475, p<0.02) when looking at direct effects and with 19% lower wages (z=4.65, df=486, p<0.001) when looking at total effects. The higher Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale scores of generalized social anxiety disorder subjects also were associated with a 10-percentage-point lower probability of earning a college degree (z=2.48, N=569, p<0.02) and a 14-percentage-point lower probability of being in a managerial, technical, or professional occupation (z=3.960, N=616, p<0.001) relative to the no-diagnosis group (Figure 2). Severity of generalized social anxiety disorder was not associated with different rates of employment or hours of work.

Work productivity

Compared with the no-diagnosis group, subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder had significantly greater impairment in work and home productivity and significantly greater overall work impairment (Table 3). Subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder and comorbid psychopathology missed a greater percentage of work time because of health than did those in the no-diagnosis group. Subjects with pure major depression had significantly greater impairment than did subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder in terms of percentage of work hours missed, work productivity, home productivity, and overall work impairment.

Disability

Current disability associated with generalized social anxiety disorder was measured with the Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale and the Sheehan Disability Scale. On the Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale, subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder rated themselves significantly more impaired in terms of current moderate alcohol use, family relations, romantic relationships, and social network than did those with no diagnosis (Table 3). Subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder and comorbid psychopathology also reported significantly greater impairment in these domains as well as in employment than did those with no diagnosis.

Subjects with major depression alone were significantly more impaired than subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder in terms of employment, family relations, romantic relationships, and desire to live (Table 3). However, when asked about lifetime disability, there were no significant differences between subjects with depression and those with pure generalized social anxiety disorder.

On the Sheehan Disability Scale, the highest disability scores across all categories of work, social life, family functioning, and total disability were observed in subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder and comorbid psychopathology (Table 3). In addition, Sheehan Disability Scale scores indicated significantly greater impairment for subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder compared with subjects who had no diagnosis.

Health-related quality of life

Subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder reported significantly lower health-related quality of life than those with no diagnosis on all subscales of the Short-Form General Health Survey except physical functioning, bodily pain, limitations in role functioning resulting from physical problems, and the standardized physical component (Table 3). Subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder and comorbid psychopathology also showed significantly greater impairment than those with no diagnosis on all the Short-Form General Health Survey subscales except the standardized physical component. Subjects with pure major depression exhibited greater impairment than did subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder on all subscales.

Suicide

During the month before participating in the survey, a significantly greater percentage of subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder than of subjects with no diagnosis endorsed thoughts that they would be better off dead or thoughts of suicide (12.2% versus 1.9%, respectively; χ2=43.14, df=1, p=0.001). Among subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder, 21.9% reported a lifetime history of suicide attempts, which was not significantly different from that found in subjects with pure major depression (19.5%) (χ2=0.17, df=1, p<0.70) but was significantly greater than that found in subjects with no diagnosis (5.2%) (χ2=48.01, df=1, p<0.001).

Discussion

Generalized social anxiety disorder is among the most prevalent—albeit underrecognized and undertreated—psychiatric disorders in the community. This study is the first to our knowledge to report direct and indirect costs of generalized social anxiety disorder in managed care. The demographic profile is congruent with other social anxiety disorder samples. The median age at onset of generalized social anxiety disorder (11.55 years) was lower than the median age at onset (16 years) in the general population sample of the National Comorbidity Survey (29). The slight overrepresentation of female subjects is similar to other epidemiological studies. Moreover, most subjects in this survey had generalized social anxiety disorder that was of a severity similar to that of patients seeking treatment. For example, the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale mean score of 74 in this population is comparable to the mean baseline pretreatment Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale score (78.0) in patients enrolled in the trial that was part of the Food and Drug Administration’s new drug application for paroxetine (12). Pure generalized social anxiety disorder was associated with significantly lower health-related quality of life and substantially impaired occupational functioning. However, subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder and comorbid psychopathology were even more impaired. Lifetime suicide attempt rates were as great in subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder as they were in subjects with current major depression. This is in contrast to the findings of Schneier and associates (3), who did not find higher suicide attempt rates in patients with social anxiety disorder. Unlike our study, Schneier et al. (3) did not assess the generalized subtype separately, and they examined lifetime versus current comorbidity. Our finding that generalized social anxiety disorder is associated with substantial indirect costs is consistent with the recent economic analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey (30).

Generalized social anxiety disorder is also associated with substantially decreased hourly wages and higher health service utilization. We computed the impact of generalized social anxiety disorder on educational and occupational attainment, controlling for age and gender (Figure 2). The average subject with pure generalized social anxiety disorder has a probability of graduating from college that is 10 percentage points lower and earns wages that are 10% lower than persons without generalized social anxiety disorder. In addition, the probability that a person with average-severity generalized social anxiety disorder holds a technical, professional, or managerial job is 14 percentage points lower than that of an otherwise healthy individual. Combined with our observation that generalized social anxiety disorder can begin in preadolescence, these findings underscore the profound effect on lifetime achievement.

We recognize several limitations of this study. All participants were members of the Dean Health Plan. To be a member, one must be employed or directly related to an employee member. As a result, this population is less likely to include individuals with generalized social anxiety disorder that is severe enough to preclude employment, thus understating the total impact of generalized social anxiety disorder in the community. In the ECA database, 22.3% of subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder reported receiving financial disability or current welfare benefits compared with 10.6% of those with no disorder (3).

Because of the substantial comorbidity in our population and the unclear extent of the contribution of generalized social anxiety disorder to effects in subjects with comorbid diagnoses, it is difficult to assess the overall effect of generalized social anxiety disorder. However, generalized social anxiety disorder was the psychiatric disorder that occurred first in 71.4% of the subjects in our study with comorbid diagnoses. Some forms of comorbidity (e.g., alcohol/substance abuse) may in some cases represent attempts at self-medication and thus may be considered causally related to generalized social anxiety disorder. It is not possible from our findings to determine if 1) generalized social anxiety disorder was the underlying etiology of the comorbidity, 2) the comorbid diagnoses were caused by the same underlying etiology as generalized social anxiety disorder, or 3) the comorbid diagnoses were caused by an independent factor not related to the etiology of generalized social anxiety disorder. We attempted to separately analyze subjects with pure generalized social anxiety disorder and to use regression analysis to control for psychiatric comorbidity. In addition, some of the impact of generalized social anxiety disorder could have been associated with psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder) that was not assessed.

There is a probable sampling bias in the study, since a greater percentage of subjects agreeing to be contacted than of subjects who asked not to be contacted screened positive for social anxiety disorder (19.1% versus 13.5%, respectively). An adjustment was made to compensate for this sampling bias in calculating the overall prevalence rate of generalized social anxiety disorder. For the same reason, the no-diagnosis group may include individuals with more psychopathology than the true underlying population. It is also possible that individuals who screened positive for social anxiety disorder were more likely to return the questionnaire, although it is not possible to adjust for this bias.

An important secondary outcome is the development of a brief and psychometrically sound screening tool for generalized social anxiety disorder. Our findings confirmed preliminary data showing the high levels of sensitivity (94%) and specificity (90%) of the three-item short form of the Social Phobia Inventory (31). The three-item version actually improved the sensitivity and specificity over the longer version and should provide a valuable tool for both research and clinical care.

Conclusions

We found that generalized social anxiety disorder is prevalent and severe in a managed care population but is undiagnosed and undertreated. Generalized social anxiety disorder is associated with lower health-related quality of life, a higher rate of lifetime suicide attempts, diminished educational and occupational attainment, and higher utilization of health care resources. The magnitude of these effects and the societal burden of generalized social anxiety disorder are similar to those of depression.

Because our findings suggest that generalized social anxiety disorder in managed care populations is similar in quality and severity to generalized social anxiety disorder studied in research treatment settings, it would be worthwhile to study whether interventions that have been shown to be efficacious in the research environment can be translated effectively to primary care patients. Given the chronic nature of generalized social anxiety disorder in this managed care sample and the likelihood that associated functional impairment may take longer to respond to treatment than symptoms alone do, long-term trials are needed to most meaningfully assess the impact of treatment. Such studies will help determine if the psychiatric comorbidity, reduced quality of life, impaired social and occupational functioning, and greater health care utilization associated with generalized social anxiety disorder can be substantially improved through the use of established treatments.

|

|

|

Received Oct. 18, 2000; revision received March 9, 2001; accepted April 19, 2001. From the Dean Foundation for Health Research and Education, Middleton, Wisc.; and Healthcare Technology Systems, Madison, Wisc. Address reprint requests to Dr. Katzelnick, Madison Institute of Medicine, Inc., 7617 Mineral Point Rd., Suite 300, Madison, WI 53717; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by GlaxoSmithKline. The authors thank Lynn Ann Parrish and Mary Bowers for administrative assistance and Sally K. Laden, M.S., for editorial assistance in manuscript preparation.

Figure 1. Screening and Diagnostic Distribution of HMO Members Invited to Participate in Study of Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder

aAccording to responses on the three-item short form of the Social Phobia Inventory (14).

bAccording to responses on the three-item depression screening questionnaire by Rost et al. (15).

cSubjects were recontacted and assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (16) and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (17).

dMania, panic disorder, or substance abuse.

Figure 2. Economic, Educational, and Occupational Impairment of a Typical HMO Member With Pure Generalized Social Anxiety Disordera Relative to a Typical Member With No Diagnosisb

aLiebowitz Social Anxiety Scale score=68.

bLiebowitz Social Anxiety Scale score=27.

1. Davidson JRT, Hughes DC, George LK, Blazer DG: The boundary of social phobia: exploring the threshold. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:975-983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Schneier FR, Heckelman LR, Garfinkel R, Campeas R, Fallon BA, Gitow A, Street L, Del Bene D, Liebowitz MR: Functional impairment in social phobia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:322-331Medline, Google Scholar

3. Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Liebowitz MR, Weissman MM: Social phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiological sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 55:322-331Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Stein MB, Berglund P: Social phobia subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:613-619Link, Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8-19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Weiller E, Bisserbe JC, Boyer P, Lepine JP, Lecrubier Y: Social phobia in general health care: an unrecognized undertreated disabling disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:169-174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Beitman BD: The relation between alcohol problems and the anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:685-695Link, Google Scholar

8. Turner SM, Beidel DC, Larkin KT: Situational determinants of social anxiety in clinic and nonclinic samples: physiological and cognitive correlates. J Consult Clin Psychol 1986; 54:523-527Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Solyom L, Ledwidge B, Solyom C: Delineating social phobia. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 149:464-470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Safren SA, Heimberg RG, Brown EJ, Holle C: Quality of life in social phobia. Depress Anxiety 1997; 4:126-133Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Jefferson JW: Social phobia: a pharmacologic treatment overview. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56(suppl 5):18-24Google Scholar

12. Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, Pitts CD, Bushnell W, Gergel I: Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized, controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280:708-713Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, Holt CS, Welkowitz LA, Juster HR, Campeas R, Bruch MA, Cloitre M, Fallon B, Klein DF: Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:1133-1141Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE, Sherwood A, Foa E, Weisler RH: Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN): new self-rating scale. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:379-386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Rost K, Burham A, Smith GR: Development of screeners for depressive disorders and substance abuse history. Med Care 1993; 31:189-200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

17. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan MF, Dunbar GC: The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry 1997; 12:232-241Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr: The MOS Short-Form General Health Survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care 1988; 26:724-735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM: The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993; 4:353-365Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kobak KA, Schaettle SC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Katzelnick DJ, Dottl SL: Computer interview assessment of social phobia in a clinical drug trial. Depress Anxiety 1998; 7:97-104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Mundt JC, Katzelnick DJ: Computerized assessment of depression and anxiety over the telephone using interactive voice response. MD Computing 1999; 16:64-68Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sheehan DV: The Anxiety Disease. New York, Bantam, 1983, p 138Google Scholar

23. International Labor Organization October Inquiry Results, 1985 and 1986, on Occupational Wages and Hours of Work and on Retail Food Prices, in Bulletin of Labour Statistics. Geneva, ILO, 1987, appendix I Google Scholar

24. Greene WH: Econometric Analysis, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ, Prentice Hall, 2000Google Scholar

25. Efron H, Tibshirani RJ: An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York, Chapman & Hall, 1993Google Scholar

26. Williams W II: A Sampler on Sampling. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1978Google Scholar

27. Blough DK, Madden CW, Hornbrook MC: Modeling risk using generalized linear models. J Health Econ 1999; 18:153-171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. McCullagh P, Nelder JA: Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed. London, Chapman & Hall, 1989Google Scholar

29. Magee WJ, Eaton WW, Wittchen H-U, McGonagle KA, Kessler RC: Agoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:159-168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Davidson JR, Ballenger JC, Fyer AJ: The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:427-435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE, Katzelnick D, Davidson JRT: The Mini-SPIN: a brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety 2001; 14:137-140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar