Neuropsychological Differences Between First-Admission Schizophrenia and Psychotic Affective Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study compared the neuropsychological functioning of patients with first-admission schizophrenia with that of patients with first-admission psychotic affective disorders. METHOD: Data came from the Suffolk County Mental Health Project, an epidemiological study of first-admission psychotic disorders. Subjects with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (N=102) and psychotic affective disorders, including bipolar disorder with psychotic features (N=72) and major depressive disorder with psychotic features (N=49), were compared on a battery of neuropsychological tests administered 2 years after the index admission. RESULTS: Subjects with schizophrenia performed worse than those with the psychotic affective disorders, even after adjusting the results for differences in demographic characteristics and general intellectual functioning. The most consistent differences were on tests of attention, concentration, and mental tracking. The two psychotic affective disorder groups were indistinguishable in performance on the neuropsychological tests. CONCLUSIONS: Even early in its course, schizophrenia is distinguishable from psychotic affective disorders by global and specific neuropsychological deficits. These deficits might contribute to the disability and poor outcome associated with schizophrenia in the mid- and long-term course.

Cognitive impairments are central features of schizophrenia and are related to functional status and other aspects of the illness (1). These deficits have been recognized for years but their status as important features of the disorder has recently received greater attention. Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia are not completely caused by the symptoms of the illness or aspects of its treatment, and they are stable over time across fluctuations in other aspects of clinical state (2). Some studies have suggested that these deficits may be partly responsive to treatment with novel antipsychotic medications (3), although they appear to be quite refractory to treatment with conventional agents (4). First-episode patients appear to have deficits in their functioning that are similar to those seen in patients with chronic illness (5, 6), although patients with poor outcome show some signs of deterioration in cognitive functioning in later life (7).

Although cognitive impairments are common in schizophrenia, they are not specific to this illness. Subjects with affective disorders also perform worse than normal comparison subjects or normative standards on many measures of cognitive functioning (8–10), as do subjects with other neuropsychiatric conditions such as head trauma, cerebrovascular accidents, seizure disorders, and dementia (11). Comparisons of the profile and magnitude of the cognitive deficits of patients with schizophrenia with those of patients with other neuropsychiatric disorders can provide information about potential etiological factors and neurobiological substrates of the deficits. For example, neuropsychological and neuropathological studies that discriminate between subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and those with schizophrenia have suggested that the cognitive impairments in these illnesses have different biological substrates (12, 13), as have comparative studies contrasting subjects with schizophrenia and subjects with temporal lobe epilepsy (14).

When patients with affective disorders were compared with patients with schizophrenia, a somewhat contradictory pattern of results emerged. Some reports suggested that subjects with affective disorders perform better overall on neuropsychological tests than subjects with schizophrenia (15). Others found limited differences in performance between the two diagnostic groups (16–24), especially in subjects with chronic illness or poor outcome (20). Finally, two studies that distinguished between psychotic and nonpsychotic affective disorders reported significant differences between patients with schizophrenia and those with nonpsychotic affective disorders but not between patients with schizophrenia and those with psychotic affective disorders (25, 26).

There are many reasons for the disparate results in these comparisons. In some studies, the subjects with affective disorders had notably chronic illness or were elderly; other studies examined young subjects with a relatively recent onset of illness. Some studies included subjects who were receiving treatment; others, medication-free subjects. Some examined inpatients; others, outpatients. Finally, some divided the sample of subjects with affective disorder into groups with major depressive disorder versus bipolar disorder; others examined heterogeneous groups. Because subjects with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder differed in family history, response to treatment, course, outcome, and other variables (27), they may have differed on tests of cognitive functioning as well.

This report compares the performance of subjects with schizophrenia, psychotic major depressive disorder, and psychotic bipolar disorder on a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment battery. Several features of this study are important. The study group was composed exclusively of first-admission patients who had psychotic symptoms at the time of admission. Consensus diagnoses were based on structured interviews and other information gathered over the 2-year follow-up in order to make a reliable distinction between major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychological assessment was conducted 2 years after the index admission. The individual tests in the battery were selected on the basis of both relevance to schizophrenia and the availability of comprehensive norms. Finally, statistical analyses compared performance both globally and specifically on individual tests and identified profiles of performance for subjects with schizophrenia and for subjects with psychotic affective disorders.

Method

Sample

The sample is part of the Suffolk County Mental Health Project cohort of consecutive first admissions with a psychotic disorder drawn from 12 psychiatric facilities in Suffolk County, N.Y., between September 1989 and December 1995. The inclusion criteria were age 15–60 years, residence in Suffolk County, and clinical evidence of psychosis. Exclusion criteria were a psychiatric hospitalization more than 6 months before the index admission, moderate or severe mental retardation, and inability to speak English (see reference 28 for more details). The initial response rate was 72%. Overall, 695 individuals who met the inclusion criteria agreed to participate in the study and were interviewed at baseline. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals after the procedures had been fully explained. After the baseline interview, subjects were interviewed by phone every 6 months and through face-to-face contact at 6, 24, and 48 months. At the 24-month follow-up, a battery of neuropsychological tests was administered.

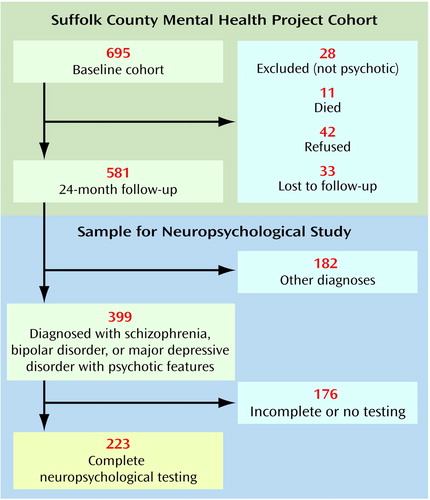

The derivation of the sample included in the analyses reported here is presented in Figure 1. The sample was made up of 223 subjects who had a consensus research diagnosis of DSM-IV schizophrenia (N=102), bipolar I disorder with psychotic features (N=72), or major depressive disorder with psychotic features (N=49) and for whom we had complete 24-month follow-up interview data, including all components of the neuropsychological test battery. Subjects with schizoaffective disorder and schizophreniform disorder were excluded from this report.

Instruments

At baseline and at each face-to-face follow-up, subjects were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (29). On the basis of the SCID interviews, medical records information, and interviews with the subjects’ relatives, consensus research DSM-III-R and DSM-IV diagnoses were reached for each participant. We used the DSM-IV diagnoses for this study.

In addition, at baseline and at each follow-up, the interviewers completed a series of rating scales, including the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (30), which rates severity of hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behavior, and formal thought disorder on a 6-point scale, and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (31), which rates severity of affective flattening, alogia, avolition, anhedonia, and attentional disorder on a 6-point scale. At the 24-month follow-up, the neuropsychological test battery was administered (the individual tests in the battery are listed in Table 1). The interviewers, all master’s-level mental health professionals, were trained by a neuropsychologist with experience in evaluating severely mentally ill subjects. The tests were scored by research assistants trained in the standard procedures for scoring each test. The 24-month follow-up interviews, including the neuropsychological assessment, usually took place in the subjects’ homes.

Data Analysis

Performance on the neuropsychological test battery was compared across the three diagnostic groups by using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Because of the unequal size of the groups, Pillai’s test was used to compare the groups. To control for the effect of potentially confounding variables, multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used. The alpha level was adjusted for multiple testing by Bonferroni correction (p<0.0025). As several of the tests in our battery were highly correlated, discriminant function analysis was used to identify a smaller number of tests that reliably distinguished among diagnostic groups. Tests with significant results (p<0.05) in the MANCOVA were included in the discriminant function analysis.

Results

Background and Illness Characteristics

The sociodemographic and psychiatric characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 2. Compared to subjects in the two psychotic affective disorder groups, subjects in the schizophrenia group were more likely to be male and nonwhite. They also had higher levels of both positive and negative symptoms, were more likely to be taking medications at the time of testing, and had a longer time lag between their first psychotic symptom and first admission. Subjects with bipolar disorder were more likely than those with either schizophrenia or major depressive disorder to be high school graduates. There were, however, no diagnostic differences in age at the time of testing and in substance use comorbidity.

Diagnostic Comparisons

Means and standard deviations for the three diagnostic groups’ neuropsychological test scores are presented in Table 1. Overall, there was a statistically significant difference among the groups in their performance on the neuropsychological tests (Pillai’s test=0.33, F=1.87, df=42, 402, p<0.01). For 13 of the 21 comparisons, the differences reached the Bonferroni corrected level of significance (p<0.0025). The results of the post hoc comparisons revealed that the schizophrenia group did significantly worse than each of the affective disorder groups. However, there were no significant differences between the bipolar disorder group and the major depressive disorder group. As a result, the analysis was repeated after combining the two affective disorder groups. This second MANOVA also showed a statistically significant overall difference between the schizophrenia group and the combined affective disorders group (Pillai’s test=0.29, F=3.83, df=21, 201, p<0.001). In addition, the subjects with schizophrenia performed significantly worse on the same individual tests in the two-group comparison as in the three-group comparison.

Diagnostic Comparisons Adjusting for Covariates

To select covariates, we first examined the relationship of demographic characteristics to performance on the neuropsychological tests. These analyses showed that the following characteristics were associated with neuropsychological test performance: age at the time of testing (Pillai’s test=0.28, F=3.70, df=21, 201, p<0.001), gender (Pillai’s test=0.39, F=6.15, df=21, 201, p<0.001), race (white versus nonwhite) (Pillai’s test=0.22, F=2.76, df=21, 201, p<0.001), and education (Pillai’s test=0.24, F=2.95, df=21, 201, p<0.001). On the other hand, medication status (receiving psychoactive medications at the time of testing) (Pillai’s test=0.14, F=1.50, df=21, 201, n.s.) and whether the physical conditions of testing were favorable (Pillai’s test=0.13, F=1.44, df=21, 201, n.s.) were not significantly associated with neuropsychological performance. Because too few subjects were abusing substances at the time of testing, we could not reliably assess the impact of this variable. However, lifetime substance use disorder was not significantly associated with performance (Pillai’s test=0.14, F=1.57, df=21, 201, n.s.). In addition, there was no association between the interval from the first psychotic symptom to the first hospitalization (log transformed owing to substantial positive skew) and neuropsychological performance (Wilks’s test=0.88, F=1.31, df=21, 193, n.s.).

On the basis of these analyses, age, gender, race, and education were selected as covariates in the MANCOVA. Scores on the Information and Vocabulary tests of the WAIS-R were also included as covariates to control for the effect of general intellectual functioning. Two MANCOVAs were conducted, one comparing the three diagnostic groups and the second comparing the schizophrenia group with the combined affective disorder group (Table 1). The results of the first MANCOVA did not indicate a statistically significant overall difference between the three diagnostic groups (Pillai’s test=0.19, F=1.10, df=38, 394, n.s.). The overall test result for comparison of the schizophrenia and the combined affective disorder groups in the second MANCOVA, however, was statistically significant (Pillai’s test=0.15, F=1.84, df=19, 197, p<0.05). Inspection of the results for the individual comparisons in both MANCOVAs revealed that the schizophrenia group had significantly worse performance than both affective disorder groups, considered separately or in combination on measures of attention, mental tracking, immediate nonsemantic verbal memory (Silly Sentences), and delayed visual memory. As before, the two groups with affective disorders did not perform significantly differently on any tests.

Only seven (10%) of the 72 subjects with bipolar disorder and three (6%) of the 49 subjects with major depressive disorder, compared with 36 (35%) of the 102 subjects with schizophrenia, had psychotic symptoms at the time of testing (χ2=24.9, df=2, p<0.001). We thus repeated the final MANCOVA for the subjects with no current psychotic symptoms at 24-month follow-up (N=177). Although the overall test comparing the schizophrenia group and the combined affective disorder group was not significant (Pillai’s test=0.17, F=1.61, df=19, 151, n.s.), the pattern of significant findings for individual comparisons (results not shown) was the same as that reported for the full sample, presented in Table 1.

Discriminant Function Analysis

Eleven neuropsychological tests were included in the discriminant analysis, including the WAIS-R Vocabulary and Information tests, along with the nine tests that showed a significant difference (p<0.05) between the schizophrenia group and the combined affective disorders group in the MANCOVA (Table 1, last two columns). Using a stepwise method, the final model retained three measures: Digit Symbol, Symbol Digit Modalities—oral, and Silly Sentences. One discriminant function that was based on these three variables accounted for more than 95% of the between-group variance (Wilks’s lambda=0.75, p<0.001). The model correctly classified 73% (N=74) of the subjects with schizophrenia and 75% (N=91) of the subjects with psychotic affective disorders.

Discussion

The major finding of this study was that at 2-year follow-up, first-admission subjects with schizophrenia performed worse on a number of neuropsychological tests compared with subjects with psychotic affective disorders, even after the analysis controlled for demographic variables and general intellectual functioning. Furthermore, the differences appeared to follow a particular pattern, in which subjects with schizophrenia performed consistently worse on tests of attention, concentration and mental tracking, visual memory, verbal fluency, and nonsemantic verbal short-term memory.

Deficits in attention and concentration have been implicated as central deficits in schizophrenia from early times (36, 37). More recently, Pearlson et al. (38) proposed involvement of the heteromodal association cortex as the neurological substrate for a range of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. The heteromodal association cortex is a diffuse functional unit that includes interconnected regions in the prefrontal, temporal, and parietal cortex and subserves a host of higher cortical functions, including focused attention, working memory, and verbal fluency. This hypothesis is further supported by the results of studies linking neuropsychological deficits with negative symptoms (39, 40). These symptoms are characterized by deficits in motivation and socialization, functions also attributed to the heteromodal association cortex system. Work by Hoff et al. (41, 42) has further suggested that these neuropsychological deficits—along with negative symptoms—are apparent early in the course of schizophrenia and persist over the long term. Thus, these deficits might represent trait markers for the illness.

The specificity of these deficits to schizophrenia was supported in a magnetic resonance imaging study (43) comparing subjects with schizophrenia, subjects with bipolar disorder, and matched normal comparison subjects. That study showed reduction in gray matter volume in heteromodal association cortex regions in schizophrenia but not in bipolar disorder. Our findings further support the hypothesis of dysfunction in the heteromodal association cortex in schizophrenia by revealing specific deficits in neuropsychological functions served by this system.

Three neuropsychological tests (Digit Symbol, Symbol Digit Modalities—oral, and Silly Sentences) explained a large proportion of the variation in neuropsychological functioning between the schizophrenia group and the psychotic affective disorders group. The Digit Symbol is a test of motor persistence, sustained attention, response speed, and visuomotor coordination (11). Symbol Digit Modalities—oral is primarily a test of complex scanning and visual tracking and is highly correlated with the Digit Symbol (11). Silly Sentences, a test of immediate nonsemantic verbal memory, assesses the contribution of meaning to retention (11).

The Digit Symbol test has been administered in three previous comparative studies (18, 25, 26). In the study by Morice (18), a comparison of the mean Digit Symbol scores of chronically ill treatment-seeking subjects with schizophrenia (mean score=5.7) and with bipolar disorder (mean score=6.5) was not statistically significant. Moreover, these chronically ill subjects performed worse than the subjects in the present study. Jeste et al. (25) compared schizophrenia subjects to psychotic and nonpsychotic depression subjects. All were over 45 years old. The subjects with schizophrenia and those with psychotic affective disorders had mean scores of 8.1 and 8.4, respectively, whereas the performance of the nonpsychotic affective disorder group was consistent with normative standards. Finally, Albus et al. (26) compared first-episode schizophrenia subjects to psychotic and nonpsychotic affective disorder subjects. The researchers combined the Digit Symbol test, the Stroop Color and Word Tests, and the Trail Making Tests to form a “visual motor processing and attention” dimension. Although test score means were not provided, the subjects with schizophrenia scored 2.2 standard deviations lower on this dimension than the normal comparison group and 1.4 standard deviation lower than the nonpsychotic affective group, but only 0.3 standard deviations lower than the psychotic affective group.

The performance of subjects with bipolar disorder in the sample described here was indistinguishable from that of subjects with major depressive disorder. The neuropsychological performance of these groups has rarely been directly compared. However, given the differences in the course and clinical outcome of these disorders (27), one might expect differences in the neuropsychological functioning as well. Our finding of no difference in the neuropsychological performance of these two groups needs to be confirmed in future studies.

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, we did not have a normal comparison group. However, almost all of the tests in our battery were well known and had widely available standard norms. Comparison with these norms in many cases confirmed poorer functioning, especially in the group with schizophrenia.

Second, as presented in Figure 1, 42 subjects refused the 24-month follow-up interview and another 33 were lost to follow-up. However, except for age, these 75 were not different from the 581 who were successfully followed up in demographic characteristics, baseline diagnosis, or other psychiatric variables. Subjects who refused or were lost were slightly older than those who were contacted (mean age=33.3 years, SD=10.6, and 29.4 years, SD=9.5, respectively) (t=3.29, df=654, p<0.01).

Third, 176 respondents did not have a complete neuropsychological assessment because they were interviewed by phone or mail, were too disturbed to be tested during the interview, or failed to complete one or more components of the assessment. There were few differences, however, between the 223 respondents who completed the battery and the 176 who did not. Subjects with schizophrenia who did not complete the neuropsychological evaluation had more severe positive symptoms compared with the subjects with schizophrenia who completed the battery (SAPS mean score=1.05, SD=0.96, and 0.70, SD=0.75, respectively) (t=2.35, df=143, p<0.05). Furthermore, subjects with bipolar disorder who did not complete the neuropsychological evaluation had more severe negative symptoms compared to subjects with bipolar disorder who completed the battery (SANS mean score=0.79, SD=0.81, and 0.45, SD=0.48, respectively) (t=2.60, df=99, p<0.05). A similar result for negative symptoms was obtained in comparing subjects with major depressive disorder who completed the neuropsychological battery with those who did not (SANS mean score=1.42, SD=1.16, and 0.69, SD=0.66, respectively) (t=2.84, df=58, p<0.01). However, neither positive symptoms in subjects with schizophrenia nor negative symptoms in subjects with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder were associated with neuropsychological performance in these diagnostic groups. Therefore, it is unlikely that exclusion of these 176 subjects biased the results of comparisons between diagnostic groups.

Finally, some authors (37, 44) have cautioned that differences in psychometric properties of tests make interpreting profiles of performance across groups less reliable than interpreting global differences. Caution is therefore necessary in interpreting the different patterns of deficits found in this study. However, it is reassuring that we obtained consistent results across different tests of the same domains of neuropsychological functioning (e.g., attention, concentration, and mental tracking). Another consideration when interpreting the different patterns of test performance across diagnostic groups is the possibility that certain abilities or tests for these abilities (in this case, tests of attention, concentration, and mental tracking) are more sensitive to global nonspecific deficits than are other abilities (37).

Conclusions

In the context of the study’s limitations, the results suggest global and specific neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia compared to psychotic affective disorders. These findings add to the growing body of clinical (45) and neurophysiological (46) evidence supporting a distinction between schizophrenia and psychotic affective disorders early in their course. There is some evidence that the neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia are associated with concurrent deficits in social and occupational functioning (1, 47). Future analyses need to assess whether these early neuropsychological deficits contribute to the poorer mid- and long-term course and outcome of schizophrenia as well. Such knowledge might prove valuable in designing early interventions for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

|

|

Received Aug. 19, 1999; revision received Feb. 15, 2000; accepted Mar. 8, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York; the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, State University of New York at Stony Brook; the Department of Psychiatry, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, New York; the Department of Veteran Affairs, Veterans Integrated Service Network 3, Bronx, NY; and Shelvata Hospital, Tel Aviv, Israel. Address reprint requests to Dr. Mojtabai, 200 Haven Ave., Apt. 6P, New York, NY 10033; [email protected] (e-mail). The Suffolk County Mental Health Project is supported by NIMH grant MH-44801. Dr. Mojtabai’s work is partly supported by NIMH grant MH-01754 and a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. The authors thank the mental health professionals in Suffolk County, the mental health project psychiatrists and staff, and the study subjects and their families and friends. They also thank Dr. Avraham Calev for help in selecting the study instruments and training the interviewers.

Figure 1. Method of Sampling Subjects With First-Admission Psychotic Disorders in the Suffolk County Mental Health Project for Participation in a Study of Neuropsychological Functioninga

aSubjects drawn from consecutive first admissions for psychotic disorders to psychiatric facilities in Suffolk County, NY., between September 1989 and December 1995.

1. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321–330Google Scholar

2. Harvey PD, Docherty NM, Serper MR, Rasmussen M: Cognitive deficits and thought disorder, II: an eight-month followup study. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:147–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Green MF, Marshall BD Jr, Wirshing WC, Ames D, Marder SR, McGurk S, Kern RS, Mintz J: Does risperidone improve verbal working memory in treatment-resistant schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:799–804Google Scholar

4. Spohn HE, Strauss ME: Relation of neuroleptic and anticholinergic medication to cognitive functions in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 1989; 98:478–486Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mohamed S, Paulsen JS, O’Leary D, Arndt S, Andreasen N: Generalized cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a study of first-episode patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:749–754Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Kester DB, Mozley LH, Stafiniak P, Gur RC: Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:124–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Harvey PD, Silverman J, Mohs RC, Parrella M, White L, Powchik P, Davidson M, Davis KL: Cognitive decline in late-life schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of geriatric chronically hospitalized patients. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 54:32–40Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Taylor MA, Abrams R: Cognitive dysfunction in mania. Compr Psychiatry 1986; 27:186–191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Brown RG, Scott LC, Bench CJ, Dolan RJ: Cognitive function in depression: its relationship to the presence and severity of intellectual decline. Psychol Med 1994; 24:829–847Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Elliot R, Sahakian BJ, McKay AP, Herrod JJ, Robins TW, Paykel ES: Neuropsychological impairment in unipolar depression: the influence of perceived failure on subsequent performance. Psychol Med 1996; 26:975–989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lezak MD: Neuropsychological Assessment, 3rd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

12. Davidson M, Harvey P, Welsh KA, Powchik P, Putnam KM, Mohs RC: Cognitive impairment in late-life schizophrenia: a comparison of elderly schizophrenic patients and patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1274–1279Google Scholar

13. Heaton R, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, Kuck J, Zisook S, Braff D, Harris J, Jeste DV: Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics: relationship to age, chronicity, and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:469–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gold J, Blaxton TA, Hermann BP, Randolph C, Fedio P, Goldberg TE, Theodore WH, Weinberger DR: Memory and intelligence in lateralized temporal lobe epilepsy and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:59–65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Goldberg TE, Gold JM, Greenberg R, Griffin S, Schulz SC, Pickar D, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR: Contrasts between patients with affective disorders and patients with schizophrenia on a neuropsychological test battery. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1355–1362Google Scholar

16. Zihl J, Gron G, Brunnauer A: Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia and affective disorders: evidence for a final common pathway disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 97:351–357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hoff AL, Shukla S, Aronson T, Cook B, Ollo C, Baruch S, Jandorf L, Schwartz J: Failure to differentiate bipolar disorder from schizophrenia on measures of neuropsychological function. Schizophr Res 1990; 3:253–260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Morice R: Cognitive inflexibility and pre-frontal dysfunction in schizophrenia and mania. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:50–54Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Franke P, Maier W, Hardt J, Frieboes R, Lichtermann D, Hain C: Assessment of frontal lobe functioning in schizophrenia and unipolar major depression. Psychopathology 1993; 26:76–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Harvey PD, Powchik P, Parrella M, White L, Davidson M: Symptom severity and cognitive impairment in chronically hospitalised geriatric patients with affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:369–374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Harvey PD, Serper MR: Linguistic and cognitive failures in schizophrenia: a multivariate assessment. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:487–493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Addington J, Addington D: Attentional vulnerability indicators in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res 1997; 23:197–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Rund BR, Orbeck AL, Landro NI: Vigilance deficits in schizophrenics and affectively disturbed patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 86:207–212Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Mintz J: Backward masking in schizophrenia and mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:939–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Jeste DV, Heaton S, Paulsen JS, Ercoli L, Harris MJ, Heaton RK: Clinical and neuropsychological comparison of psychotic depression with nonpsychotic depression and schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:490–496Link, Google Scholar

26. Albus M, Hubmann W, Wahlheim C, Sobizack N, Franz U, Mohr F: Contrasts in neuropsychological test profiles between patients with first-episode schizophrenia and first-episode affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 94:87–93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Paykel ES (ed): Handbook of Affective Disorders, 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingston, 1992Google Scholar

28. Bromet E J, Schwartz J, Fennig S, Geller L, Jandorf L, Kovasznay B, Lavelle J, Miller A, Pato C, Ram R, Rich C: The epidemiology of psychosis: the Suffolk County Mental Health Project. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:243–255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

31. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

32. Spreen O, Strauss E: A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

33. Trenerry MR, Crosson B, DeBoe J, Leber WR: Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1989Google Scholar

34. Benton AL, Hamsher KD: Multilingual Aphasia Examination: Manual of Instructions. Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1978Google Scholar

35. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd ed. New York, HarperCollins, 1996Google Scholar

36. Kraepelin E: Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Translated by Barclay RM, edited by Robertson GM. Edinburgh, E & S Livingstone, 1919Google Scholar

37. Randolph C, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR: The neuropsychology of schizophrenia, in Clinical Neuropsychology, 3rd ed. Edited by Heilman KM, Valenstein E. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1993, pp 499–522Google Scholar

38. Pearlson GD, Petty RG, Ross CA, Tien AY: Schizophrenia: a disease of heteromodal association cortex? Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 14:1–17Google Scholar

39. Basso MR, Nasrallah HA, Olson SC, Bornstein RA: Neuropsychological correlates of negative, disorganized and psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1998; 31:99–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Andreasen NC, Olsen S: Negative v positive schizophrenia: definition and validation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:789–794Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Hoff AL, Sakuma M, Wieneke M, Horon R, Kushner M, DeLisi LE: Longitudinal neuropsychological follow-up study of patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1336–1341Google Scholar

42. Hoff AL, Riordan H, O’Donnell DW, Morris L, DeLisi LE: Neuropsychological function of first-episode schizophreniform patients. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:898–903Link, Google Scholar

43. Schlaepfer TE, Harris GJ, Tien GJ, Peng LW, Lee S, Federman EB, Chase GA, Barta PE, Pearlson GD: Decreased regional cortical gray matter volume in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:842–848Link, Google Scholar

44. Chapman LJ, Chapman JP: The measurement of differential deficit. J Psychiatr Res 1978; 14:303–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Bromet EJ, Jandorf L, Fennig S, Lavelle J, Kovasznay B, Ram R, Tanenberg-Karant M: Premorbid and clinical predictors of short-term course in first-admission psychotic patients: preliminary results. Psychol Med 1996; 26:953–962Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Salisbury DF, Shenton ME, Sherwood AR, Fischer IA, Yurgelun-Todd DA, Tohen M, McCarley RW: First-episode schizophrenic psychosis differs from first-episode affective psychosis and controls in P300 amplitude over left temporal lobe. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:173–180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Addington J, Addington D: Neurocognitive and social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:173–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar