Cross-Sectional Study of Older Outpatients With Schizophrenia and Healthy Comparison Subjects: No Differences in Age-Related Cognitive Decline

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Little is known about the progression of cognitive deficits in older, community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia, especially in comparison to healthy subjects. METHOD: The authors examined the relationship of age to performance on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale in 116 outpatients with schizophrenia and 122 normal comparison subjects. Subjects ranged in age from 40 to 85 years. RESULTS: Dementia Rating Scale scores were lower in the schizophrenia group but correlated negatively with age in both groups, with no significant differences seen between the schizophrenia and normal comparison groups in slopes that depicted age-related variation. CONCLUSIONS: This cross-sectional study suggests a relatively stable long-term course of cognitive impairment in individuals with schizophrenia, with no evidence of faster cognitive decline in outpatients with schizophrenia than in normal comparison subjects.

Controversy exists regarding the long-term course of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. While a study of institutionalized elderly patients found a high rate of non-Alzheimer’s dementia (1) and an apparently accelerated rate of cognitive decline (2), several longitudinal and cross-sectional studies of younger patients with schizophrenia failed to find cognitive deterioration (3–5). Conclusions from previous investigations were often limited, however, by variable diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, inadequate cognitive assessment, and absence of comparison groups. Few studies have examined the course of cognitive impairment in aging outpatients with schizophrenia. The number of older patients with schizophrenia is expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades (6), and most such patients live in the community rather than in institutions (7).

The present cross-sectional investigation of middle-aged and elderly patients used DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria for diagnosis, included a group of normal comparison subjects, and employed a standardized instrument for assessing global cognitive performance, the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (8). We hypothesized that Dementia Rating Scale scores would worsen with advancing age in both the schizophrenia and normal comparison groups, and the slope depicting age-related variation in the Dementia Rating Scale score would be steeper for the subjects with schizophrenia.

Method

Subjects with schizophrenia (N=116) were recruited from local medical centers, county mental health facilities, and private physicians. Those who were 40–85 years of age, living in the community, and whose onset of illness occurred before age 45 were chosen to participate. Diagnoses were determined by using the patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R or DSM-IV (9, 10). The schizophrenic outpatients were a mean age of 56.6 years (SD=9.9), had a mean of 12.6 years (SD=2.4) of education, and a mean illness duration of 30.9 years (SD=11.3); 78% (N=90) were male, and 77% (N=89) were Caucasian. Although all were outpatients at the time of study, 27% (N=31) had previously been hospitalized for more than 3 years, 59% (N=69) for 2 months to 3 years, and 14% (N=16) for less than 2 months. On average, the patients had two axis III comorbid medical conditions (SD=1.7). Exclusion criteria were 1) too physically or psychiatrically unstable to undergo assessments, 2) no corroborating source for subject history, 3) history of serious violence toward others, 4) history of head injury with loss of consciousness for more than 30 minutes, 5) current seizure disorder, or 6) substance dependence. Findings from a subset of these patients have been reported previously (11).

Normal comparison subjects (N=122), free of any major neuropsychiatric disorders, were recruited from the local community. These subjects were a mean age of 64.6 years (SD=13.0), and had a mean of 13.3 years (SD=2.6) of education; 37% (N=45) were male, and 67% (N=82) were Caucasian. They had on average 2.2 axis III comorbid medical conditions (SD=1.9).

Each subject provided written informed consent to participate in the research program.

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (12) was used to rate severity of psychopathologic symptoms. The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (8) was chosen to assess global cognitive function, since it is reasonably comprehensive, standardized, easy to administer (taking about 40 minutes), and is less prone to restricted range effects (i.e., floor and ceiling effects) than briefer measures.

For demographic and clinical comparisons of groups, Student’s t tests were employed. The slope of the regression of Dementia Rating Scale impairment on age was calculated separately for the schizophrenia patients and normal comparison subjects, and the equivalence of these regression weights was tested (13). To meet parametric assumptions, Dementia Rating Scale scores were transformed by using the following equation: Dementia Rating Scale impairment=log10 (145–Dementia Rating Scale score). All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

Normal comparison subjects were older than the schizophrenic subjects (t=5.3, df=236, p<0.001), although the age range of the two groups was identical. The schizophrenic group had more men (χ2=41.9, df=1, p<0.001) and was less educated (t=2.03, df=236, p=0.02) than the normal comparison group. The two groups were similar in the number of comorbid medical conditions and proportion of Caucasians. It was no surprise that the schizophrenic subjects had higher BPRS scores (mean=33.2, SD=8.0) than the normal comparison subjects (mean=22.5, SD=3.5) (t=13.9, df=229, p<0.0001). The schizophrenia group also had lower Dementia Rating Scale scores (mean=132.3, SD=10.1) than did the normal comparison subjects (mean=139.3, SD=3.6) (t=7.28, df=236, p<0.0001).

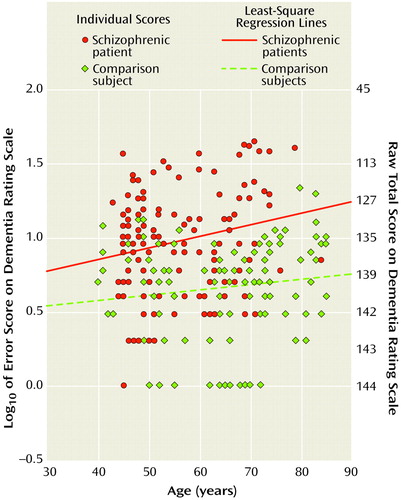

Figure 1 shows the slopes depicting age-related variation in the Dementia Rating Scale impairment score for the schizophrenic and normal comparison subjects. The slope for the schizophrenic group was 0.007 (r=0.21, df=114, p=0.03), and the slope for the normal comparison group was 0.004 (r=0.16, df=120, p=0.08). There was no significant difference between these slopes (F=0.81, df=1, 234, p=0.37). Because of age and gender differences between the groups, analyses were also conducted on age- and gender-matched subsamples; the results were similar.

Discussion

While global cognitive impairment was worse in the subjects with schizophrenia than in normal comparison subjects, there was no evidence of steeper age-related cognitive decline in those with schizophrenia. This is remarkable considering that the subjects in the schizophrenia group had been ill for many years, with all the well-known antecedents, accompaniments, and consequences of a severe psychiatric disorder. Our results support the notion of stable encephalopathy in schizophrenia (3–5).

Regarding study group characteristics, we did not include adults aged 18–39 because of considerable differences between young adult and elderly patients in variables such as age at onset and duration of illness, daily neuroleptic dose, and prevalence of substance abuse. Patients with late-onset schizophrenia were excluded because of known differences in cognitive performance that might confound the findings (14). The primary limitation of the current investigation was its cross-sectional design, with its inherent cohort effects such as survival and preferential recruitment of less ill patients.

The present results differ from those that were based on chronically institutionalized patients, which found a high rate of dementia in elderly patients with schizophrenia (1, 2). Since the present study group was somewhat younger than those of the earlier studies, a possibility of abnormally rapid cognitive decline in very old patients cannot be excluded. Additionally, our community-dwelling patients might be expected to show a milder course of illness than the institutionalized ones. As stressed by Cohen (7), however, community-dwelling individuals are far more representative of the population of older schizophrenia patients. The current findings also contrast with our previous study, which reported that span of apprehension performance and pupillary responses showed a steeper age-related slope in schizophrenia patients than in normal comparison subjects (15). This discrepancy may be due to a smaller sample size (33 patients) in the previous investigation, or there may be differential rates of decline on certain specific versus global cognitive measures.

In summary, the present cross-sectional study suggests that community-dwelling older patients with schizophrenia do not seem to have a rapid rate of global cognitive decline. Long-term prospective investigations are needed to confirm and elaborate on these findings.

Presented in part at the 12th annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, New Orleans, March 14–17, 1999, and the 152nd annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, May 15–20, 1999. Received July 23, 1999; revision received Dec. 23, 1999; accepted Jan. 3, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, and the VA San Diego Healthcare System. Address reprint requests to Dr. Eyler Zorrilla, Research Health Scientist, VISN 22 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, VA San Diego Healthcare System, 3350 La Jolla Village Dr., San Diego, CA 92161; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-43695, MH-49671, MH-45131, MH-19934, and by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Figure 1. Age-Related Variation in Cognitive Impairmenta for 116 Older, Community-Dwelling Subjects With Schizophrenia and 122 Healthy Comparison Subjects

aAs measured by the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (8).

1. Davidson M, Harvey P, Welsh KA, Powchik P, Putnam KM, Mohs RC: Cognitive functioning in late-life schizophrenia: a comparison of elderly schizophrenic patients and patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1274–1279Google Scholar

2. Harvey PD, Silverman JM, Mohs RC, Parrella M, White L, Powchik P, Davidson M, Davis KL: Cognitive decline in late-life schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of geriatric chronically hospitalized patients. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:32–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rund BR: A review of longitudinal studies of cognitive functions in schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:425–435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Goldberg TE, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR: Course of schizophrenia: neuropsychological evidence for a static encephalopathy. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:797–804Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Heaton R, Paulsen J, McAdams LA, Kuck J, Zisook S, Braff D, Harris MJ, Jeste DV: Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia: relationship to age, chronicity and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:469–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Jeste DV, Alexopoulos GS, Bartels SJ, Cummings JL, Gallo JJ, Gottlieb GL, Halpain MC, Palmer BW, Patterson TL, Reynolds CF III, Lebowitz BD: Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: research agenda for the next two decades. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:848–853Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cohen CI: Outcome of schizophrenia into later life: an overview. Gerontologist 1990; 30:790–797Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Mattis S: Dementia Rating Scale. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1973Google Scholar

9. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1986Google Scholar

10. First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV—Patient Edition (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

11. Evans JD, Negron AE, Palmer BW, Paulsen JS, Heaton RK, Jeste DV: Cognitive deficits and psychopathology in institutionalized versus community-dwelling elderly schizophrenia patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1999; 12:11–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertaining and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:97–99Google Scholar

13. Kirk RE: Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Monterey, Calif, Brooks/Cole, 1982Google Scholar

14. Jeste DV, Harris MJ, Krull A, Kuck J, McAdams LA, Heaton R: Clinical and neuropsychological characteristics of patients with late-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:722–730Link, Google Scholar

15. Granholm E, Morris S, Asarnow RF, Chock D, Jeste DV: Accelerated age-related decline in processing resources in schizophrenia: evidence from pupillary responses recorded during the span of apprehension task. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1999; 6:30–43Google Scholar