Is Placebo Response the Same as Drug Response in Panic Disorder?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors used seven definitions of response in panic disorder to compare patient-rated improvements in quality of life between patients with panic disorder who responded to sertraline and those who responded to placebo.METHOD: They combined and examined data from two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, flexible-dose studies of panic disorder (N=302).RESULTS: Significant differences in quality of life between patients who responded to sertraline and those who responded to placebo were apparent across all the definitions of clinical response.CONCLUSIONS: Patients who respond to placebo in panic disorder treatment studies may show symptom relief but may not experience improvement in quality of life. Determinations of quality of life should be included as components of both standard clinical assessment and clinical treatment studies of patients with panic disorder.

Panic disorder treatment studies have traditionally used change in the frequency of full-symptom panic attacks as the primary outcome measure, but panic attacks are merely one component of this syndrome, and reliance on them as a sole measure does not fully represent clinical improvement. Some studies (1) have reported that over 50% of placebo-treated patients were free of panic attacks at the end of the trial. Stimulated by these obvious limitations with this commonly accepted primary endpoint, the National Institute of Mental Health convened a consensus conference to standardize assessment for panic disorder studies. A multidimensional battery that measures panic attack frequency and intensity, anticipatory anxiety, phobic avoidance, and overall functional impairment was recommended (2). The significance of this recommendation was underscored by a study (3) demonstrating that patients treated with placebo who were free of panic attacks had significantly higher levels of anticipatory anxiety, phobic distress, and depression as well as greater functional impairment than patients taking active medication who were free of panic attacks.

The current investigation assesses potential differences between patients with panic disorder who responded to sertraline or to placebo by evaluating changes on a patient-rated measure of quality of life. Response to treatment for panic disorder was defined by using seven criteria sets of varying degrees of rigor to assess the relationship between clinical response and quality of life. On the basis of the findings of Shear et al. (3), we hypothesized that patients who responded to sertraline would not only demonstrate improvement in clinical ratings of panic disorder severity but also show significantly greater improvement in quality of life than patients who responded to placebo.

Method

The analysis combines data from two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, 10-week, flexible-dose studies of sertraline compared with placebo in the treatment of panic disorder (4–6). Three hundred fifty-one patients were randomly assigned to treatment (173 to sertraline; 178 to placebo). The details of the study design can be found in the previously published studies (4–6).

Frequency (number/week) of full panic attacks, as well as limited symptom attacks, were recorded in a diary completed daily by each patient and converted into weekly ratings on the Modified Sheehan Panic and Anticipatory Anxiety Scale (7). Overall improvement was assessed by using the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity of illness and improvement scales (8) administered initially weekly and later biweekly during the 10-week treatment period. Quality of life was assessed through use of a validated measure of quality of life, the short form of the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (9), administered at baseline and week 10 (or endpoint if treatment was discontinued earlier).

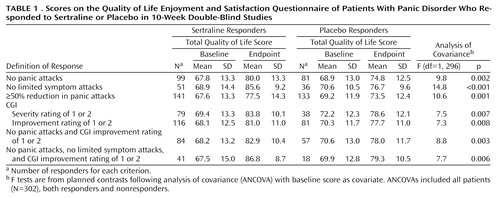

An analysis of covariance based on the change from baseline in the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire score as the dependent variable was executed for each response criterion. The model included terms for baseline Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire score as a covariate, response (yes or no according to the definition of response), study, treatment (sertraline or placebo), and a treatment-by-response interaction. Patients who responded to sertraline were contrasted with those who responded to placebo.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences between the sertraline and placebo responders on any baseline demographic or clinical characteristic, including Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire scores. Of the patients randomly assigned to sertraline or placebo groups, 147 of the 173 patients given sertraline and 155 of the 178 given placebo had at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment and a Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire rating at endpoint, yielding a final group of 302 patients for analysis.

There were highly significant differences in the total Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire endpoint scores between sertraline and placebo responders across all seven definitions of response (Table 1). Examination of individual items on the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire revealed that the effects were apparent across most aspects of quality of life. No significant differences in Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire scores were observed between placebo and sertraline nonresponders for any of the definitions of response evaluated.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that improvement in a quality of life measure can distinguish true medication response from placebo response. Improvement in quality of life statistically differentiated sertraline and placebo responders on seven clinical response criteria sets of varying rigor. These results imply that placebo responders in panic treatment studies exhibit symptom relief but not clinically meaningful improvement in quality of life. This is clinically important because improvement in quality of life is essential for successful treatment and may affect compliance.

From a research perspective, the addition of improvement in quality of life to the definition of treatment response may enhance the discrimination of drug-placebo differences. Without concurrent consideration of quality of life benefits, the utility of new treatments for panic disorder may be underestimated. Our findings, taken together with data about functional impairment and diminished quality of life in patients with panic disorder (10, 11), reinforce recommendations for inclusion of quality of life assessment in panic disorder treatment studies and in clinical practice (2).

Several limitations to our findings should be noted. The Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire is a self-report measure. Although the subjective sense of quality of life is an important aspect of the concept, we need to confirm our findings with independent assessments of work and social functioning. The highly selected nature of the patient cohort and the post hoc nature of the analyses performed must also be acknowledged as limitations of this study. Studies examining the generalizability of these results a priori across a more heterogeneous group of patients with panic disorder and comorbid psychiatric and medical illnesses are needed.

In summary, in this study of patients with panic disorder, quality of life improved more for responders to medication than for placebo responders. This suggests that increased attention to the assessment of the patients’ perceptions of their quality of life may be warranted in both clinical practice and treatment studies.

|

Presented in part at the 151st annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Toronto, May 30–June 4, 1998; the meeting of the Collegium Internationale Neuro-Psychopharmacologicum, Glasgow, July 13–16, 1998; and the meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Kamuela, Hawaii, Dec. 8–12, 1997. Received March 25, 1999; revisions received Aug. 5 and Sept. 24, 1999; accepted Nov. 5, 1999. From the Psychopharmacology Research Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego; the Psychiatric Service, San Diego Veterans Health System; the Anxiety Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and Pfizer, Inc., New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Rapaport, Psychopharmacology Research Program, UC San Diego, Department of Psychiatry, 8950 Villa La Jolla Dr., Number 2243, La Jolla, CA 92037; [email protected]. Supported by Pfizer, Inc.

1. Cross-National Collaborative Panic Study, Second Phase Investigators: Drug treatment of panic disorder: comparative efficacy of alprazolam, imipramine, and placebo. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:191–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Shear MK, Maser JD: Standardized assessment for panic disorder research: a conference report. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:346–354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Shear MK, Leon AC, Pollack MH, Rosenbaum JF, Keller MB: Pattern of placebo response in panic disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:273–278Medline, Google Scholar

4. Rapaport MH, Wolkow RM, Clary CM: Methodologies and outcomes from the sertraline multicenter flexible dose trials. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998; 34:183–189Medline, Google Scholar

5. Pohl RB, Wolkow RM, Clary CM: Sertraline in the treatment of panic disorder: a double-blind multicenter trial. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1189–1195Google Scholar

6. Pollack MH, Otto MW, Worthington JJ, Manfro GG, Wolkow R: Sertraline in the treatment of panic disorder: a flexible dose multicenter trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:1010–1016Google Scholar

7. Grebb JA: Psychiatric rating scales, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 5th ed. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, pp 534–552Google Scholar

8. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

9. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:321–326Medline, Google Scholar

10. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Johnson J, Greenwald S: Panic attacks in the community: social morbidity and health care utilization. JAMA 1991; 265:742–746Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Katerndahl DA, Realini JP: Quality of life and panic related work disability in subjects with infrequent panic and panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:153–158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar