Evaluation of Competence to Consent to Assisted Suicide:Views of Forensic Psychiatrists

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Mental health evaluation of competence to consent has been proposed as an important safeguard for patients requesting assisted suicide, yet mental health professionals have not developed guidelines or standards to aid in such evaluations. The authors surveyed a national sample of forensic psychiatrists in the United States regarding the process, thresholds, and standards that should be used to determine competence to consent to assisted suicide. METHOD: An anonymous questionnaire was sent to board-certified forensic psychiatrists between August and October 1997. RESULTS: Of the 456 forensic psychiatrists who were sent the questionnaire, 290 (64%) responded. Sixty-six percent believed that assisted suicide was ethical in at least some circumstances, and 63% thought that it should be legalized for some competent persons. Twenty-four percent indicated that it was unethical for psychiatrists to determine competence; however, 61% thought such an evaluation should be required in some or all cases. Seventy-eight percent recommended a very stringent standard of competence. Seventy-three percent believed that at least two independent examiners were needed to determine competence, and 44% favored requiring judicial review of a decision. Fifty-eight percent believed that the presence of major depressive disorder should result in an automatic finding of incompetence. Psychiatrists with ethical objections to assisted suicide advocated a higher threshold for competence and more extensive review of a decision. CONCLUSIONS: The ethical views of psychiatrists may influence their clinical opinions regarding patient competence to consent to assisted suicide. The extensive evaluation recommended by forensic psychiatrists would likely both minimize this bias and assure that only competent patients have access to assisted suicide, but the process might burden terminally ill patients.

Mental health evaluation has been proposed as an important safeguard for patients requesting physician-assisted suicide. Mental health experts have been identified as the persons best qualified to protect those patients’ autonomy by determining whether the request is competent and voluntary or the result of distorted judgment from a mental disorder such as depression (1–3).

There are several unanswered practical issues in assessing the capacity of a patient who wants to hasten death. In a survey of Oregon psychiatrists (4), 6% were very confident, 43% were somewhat confident, and 51% were not at all confident that they could, in the context of a single consultation, determine if a mental disorder or depression impaired the judgment of a patient requesting assisted suicide. Because psychiatry has viewed suicidality as a priori psychopathological, mental health professionals have neither had experience in determining specific competence to consent to assisted suicide nor developed guidelines and independent standards for this evaluation. Whether psychiatrists can agree about what these standards and guidelines should be is an unresolved question.

Among psychiatrists, forensic psychiatrists have the greatest expertise in assessing decision-making capacity in a variety of situations. This study reports the results of a national survey of forensic psychiatrists about the process, thresholds, and standards that they believe mental health professionals should use in assessing a terminally ill patient’s capacity to consent to assisted suicide.

METHOD

Forensic psychiatrists in the United States were identified from the membership of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, the principal forensic psychiatric organization in the United States. To obtain some uniformity in the knowledge base and clinical experience of survey respondents, only forensic psychiatrists who, as of April 1997, were listed as having certification from the American Board of Forensic Psychiatry or subspecialty certification in forensic psychiatry from the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology were included. The survey was based on a previous survey of psychiatrists’ views on assisted suicide (4) and on subsequent discussions with mental health professionals. In addition to requesting demographic data, the survey explored the psychiatrists’ personal views on the ethical acceptability of suicide and assisted suicide, the situations in which these practices should be legalized, and the appropriate role of psychiatrists in evaluating patients who request assisted suicide. We queried the psychiatrists on the process for evaluating competence, who should have the authority to determine competence, the threshold that should be used in this determination, and which, if any, mental disorders should automatically deem the person incompetent. “Physician-assisted suicide” was defined as “a physician provides a prescription for a medication to a requesting patient solely for use in causing the patient’s death.” “Terminal illness” was defined as “a medical condition in which the patient’s prognosis for living beyond six months is extremely poor.”

Each forensic psychiatrist was mailed a copy of the survey, a reminder postcard, and then a second copy of the survey with a simultaneous reminder phone call. No identifying data were placed in the questionnaire. To allow tracking of questionnaires and maximize the return rate, envelopes were coded with an identifying number. Responses were not reviewed until the survey had been separated from the identifying envelope. The survey was exempted from the need for written informed consent by the institutional review board at the Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The surveys were returned between August and October 1997.

Associations between items or groups of respondents were compared using the chi-square test for multiple responses or Student’s t test for continuous variables. All p values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Of 456 board-certified forensic psychiatrists identified, 290 (64%) returned the survey. The survey was returned by 90 of 144 (63%) respondents from the northeastern United States, 51 of 85 (60%) from the north central United States, 80 of 123 (65%) from the southern United States, and 63 of 101 (62%) from the western United States. The respondents’ mean age was 51.3 years (SD=11.3), 87% (N=249 of 287) were male, and 92% (N=260 of 284) were Caucasian. Table 1 outlines other personal, professional, and practice characteristics of the survey respondents.

Forensic psychiatrists had substantial professional and personal experiences with end-of-life situations. Personally, 54% (N=155 of 287) had cared for a friend or family member who had a terminal illness. Two-thirds (67%, N=191 of 287) had observed significant pain or suffering in a family member or friend who was dying. Professionally, 74% (N=213 of 286) had evaluated the competence of a patient whose refusal of treatment would have resulted in the patient’s death.

Table 2 outlines the respondents’ views on suicide and assisted suicide for competent individuals. Because of the small number of psychiatrists who responded that assisted suicide was solely the prerogative of the competent patient, this group was combined in subsequent analyses with those respondents who believed assisted suicide ethical under some circumstances. Although 80% of respondents (N=231 of 287) indicated that they considered suicide (not physician-assisted) ethical in some or all circumstances, fewer (66%, N=188 of 287) believed that suicide with a physician’s assistance was ever ethical. The mean score on the 10-point measure of importance of religion/spirituality was 6.6 (SD=3.0) for those who believed assisted suicide was never acceptable and 4.7 (SD=3.0) for those who believed assisted suicide was sometimes or always acceptable (t=4.87, df=280, p<0.001). Ethnicity was also associated with views on assisted suicide. Of 24 non-Caucasian respondents, 63% (N=15) indicated that physician-assisted suicide was never acceptable, compared to 32% (N=82) of the 257 Caucasian respondents (χ2=9.14, df=1, p=0.003). There was no significant effect of age, gender, or years in forensic practice on attitudes toward assisted suicide.

Overall, there was a strong association between attitudes toward suicide and assisted suicide (χ2=124.0, df=1, p<0.001). Of the 56 psychiatrists who believed suicide was never acceptable, 98% (N=55) also believed physician-assisted suicide was not acceptable, suggesting that for these psychiatrists what is objectionable about assisted suicide may be the suicide per se. However, 19% (44 of 230) of psychiatrists who thought that suicide might be acceptable indicated that physician-assisted suicide was not, suggesting that for these respondents the unacceptable part of assisted suicide was the physician’s assistance.

We asked respondents to outline the conditions under which physician-assisted suicide should be legally permitted for a competent patient. Thirty-seven percent (N=104) responded “never,” 19% (N=52) would legalize physician-assisted suicide only for the terminally ill, 39% (N=110) would legalize it for patients who are either terminally ill or hopelessly ill with physical suffering but not terminally ill (such as patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), and 5% (N=15) would legalize it for any competent patient.

The forensic psychiatrists were asked to answer a series of questions regarding the role of mental health evaluation in determining the competence of patients who requested physician-assisted suicide. Three percent (N=8) of the psychiatrists believed that a psychiatric evaluation was not necessary as a safeguard, and 24% (N=70) indicated that psychiatric participation in determining competence would be unethical. The remaining respondents indicated that this evaluation should be recommended but not required (N=35, 12%), required in some cases (N=62, 22%), and required in all cases (N=112, 39%). Psychiatrists who responded that assisted suicide was unacceptable and those who responded that it was sometimes or always acceptable differed significantly in their views of the psychiatrist’s role (χ2=112.6, df=4, p<0.001). Sixty-one percent (N=60) of the psychiatrists who believed that physician-assisted suicide was never acceptable also believed that psychiatric evaluation in these cases would be unethical. The second most common response among those who believed that physician-assisted suicide was never acceptable (N=28, 28%) was that the safeguard should be required in all cases. In contrast, of the 188 psychiatrists who believed that physician-assisted suicide was ethical under some or all circumstances, 45% (N=84) believed that a psychiatric evaluation should be required in all cases, 29% (N=55) indicated that it should be required in some cases, and 17% (N=32) indicated that it should be recommended but not required.

Table 3 outlines the processes and standards favored by respondents for competence assessments of patients desiring physician-assisted suicide and the relationship between the psychiatrists’ beliefs about the ethical acceptability of assisted suicide and the rigor of the standards. Psychiatrists who responded that participation by psychiatrists in the evaluation was unethical (N=70) were excluded from the remaining comparisons.

Overall, 78% of the psychiatrists indicated that a very stringent standard should be used to determine competence to consent to physician-assisted suicide, even if this higher standard might disallow some competent persons the option. Forensic psychiatrists who believed that assisted suicide was not ethically acceptable thought that the standards should be higher than those who thought it was ethically acceptable in some or all cases. Ninety percent of all respondents indicated that if judicial review were used in the evaluation, the legal standard of proof for competence should be more certain than the “preponderance of evidence” standard used in civil trials; that is, proof of competence should use either a “clear and convincing” standard, such as that used in civil commitment proceedings or a standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt,” such as that used in criminal trials.

Only 27% of the forensic psychiatrists (N=57 of 213) believed that one independent psychiatric examiner was sufficient to determine a patient’s capacity to participate in physician-assisted suicide (Table 3). The majority (73%, N=156 of 213) believed that at least two independent examiners were needed. Psychiatrists who thought that assisted suicide was never acceptable endorsed the need for more examiners than those who believed it was ethical in some or all situations. Fifty-nine percent (N=130 of 219) believed that this evaluation could only be performed by a psychiatrist from an approved panel or with forensic certification. Only 11% (N=23 of 219) thought that any licensed physician could competently perform the capacity evaluation, although 45% (N=98 of 219) indicated that all psychiatrists could perform this evaluation. Only 10% (N=22 of 214) of the forensic psychiatrists believed that the evaluation of the consulting psychiatrist was sufficient to provide closure for determining decision-making capacity. Twenty-one percent (N=46 of 214) would add a local administrative review, and 44% (N=95 of 214) would require judicial review of the decision.

Forty-seven percent (N=100 of 211) thought that a surrogate decision maker such as a health care proxy should be permitted to consent to physician-assisted suicide on behalf of an incompetent patient. Psychiatrists who considered assisted suicide unacceptable were less likely to endorse authorizing surrogate decision-making for assisted suicide (Table 3).

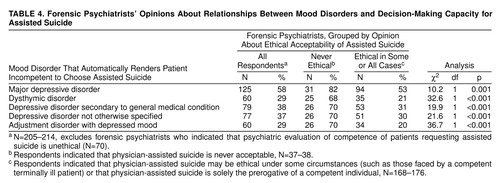

Finally, many respondents believed that the presence of a mood disorder should automatically result in a finding of incapacity to consent to assisted suicide (table 4). Fifty-eight percent (N=125 of 214) believed that the presence of major depressive disorder should result in an automatic finding of incompetence. Between 29% (N=60 of 207) and 38% (N=79 of 208) thought that other less severe affective conditions such as dysthymia and adjustment disorder should automatically result in a finding of incompetence. Those who believed that assisted suicide was never ethically acceptable were more likely to consider a patient automatically incompetent if a mood disorder was present (table 4).

DISCUSSION

We surveyed board-certified forensic psychiatrists in the United States to determine their attitudes toward assisted suicide and to elicit their opinions on standards for competence assessment of patients who desire assisted suicide. Sixty-six percent of respondents to our survey believed that assisted suicide was ethical in some circumstances, and 63% believed that it should be legal for some people. These proportions are similar to those found in regional surveys of psychiatrists and other physicians that had response rates of greater than 50% (4–7).

As voters, legislatures, and physicians consider legalization of physician-assisted suicide, they have endorsed mental health evaluation as part of the process for determining which patients should be allowed to participate (8). A primary goal of mental health evaluation is to establish the competence of the patient to consent to assisted suicide. Competence to consent to treatment includes four elements—ability to communicate a choice, factual understanding of the issues, appreciation of the situation and its consequences, and rational manipulation of the information (9). The Oregon Death with Dignity Act, which specifically outlines the mental health professional’s role as determining whether a mental disorder or depression causes impaired judgment, focuses on two of these elements― the ability of mental disorders (especially depression) to impair the appreciation of one’s situation and the consequences of decisions and the ability to rationally manipulate information (10).

The standards and thresholds for deciding whether a person has the specific capacity to consent to physician-assisted suicide cannot be scientifically determined (11). Thresholds for levels of incompetence vary by situation and may reflect social goals in tension—the degree to which society seeks to strike a balance between self-determination and protection of the patient. Standards and thresholds develop through discussion, debate, consensus, and legal decisions about competence to make particular decisions or to perform specific acts. There are regional variations in these standards. For example, in Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health, the Supreme Court affirmed that Missouri could require a “clear and convincing” standard of proof for withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, but other states were not required to adopt this higher standard (12, 13).

The psychiatric community is only beginning to discuss standards and thresholds regarding assisted suicide. As such, it is not surprising that we found a lack of consensus about the process and standards that might be used to determine competence for assisted suicide. Many forensic psychiatrists, however, would support procedural and legal safeguards for patients choosing assisted suicide. For the majority of respondents, a patient requesting assisted suicide would be found competent after an evaluation by two independent examiners, followed by judicial or local administrative review, rendering a determination of competence at a clear and convincing level of proof. The presence of major depression automatically would result in a finding of incompetence. In contrast, some courts have stated that the presence of a mental disorder does not automatically infer incompetence to make medical decisions (14–16).

Despite the fact that the majority of forensic psychiatrists support legalization of assisted suicide, they appear to view it as an extraordinary procedure similar to treatment with electroconvulsive therapy (11) or, in some states, antipsychotic medications. These other psychiatric treatments were designated “extraordinary” because legislatures, courts, or voters were concerned that without protection, they presented an unacceptable level of risk of patient abuse (11). In the case of assisted suicide, even respondents who support legalization appear to perceive a substantial risk to vulnerable patients. Although our study suggests that the majority of forensic psychiatrists consider assisted suicide extraordinary, it is not clear if the general public wants these careful procedural reviews. For example, the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, which was upheld by 60% of Oregonians, does not mandate a psychiatric evaluation in every case (10).

Our findings support the view that mental health evaluation would be an effective safeguard in preventing assisted suicide that results from a mental disorder, but any procedure incorporating safeguards would need to minimize the burden to patients. The extensive procedure for determining competence recommended by respondents might be physically difficult for debilitated dying persons to tolerate. In the Netherlands, most cases of euthanasia and assisted suicide have occurred when the patient is assessed by the primary care physician as having less than 1 week to live (17). Because only very vigorous terminally ill persons might be able to complete the level of review recommended by respondents to this survey, some persons might choose to obtain or take a lethal prescription before they are too weak and debilitated to complete the evaluation.

Respondents objected to legalized physician-assisted suicide on several grounds. Some believed that suicide itself was unacceptable. Others objected not to suicide but to physician involvement. Psychiatrists particularly may object to suicide and assisted suicide because they believe that this choice is ultimately a symptom of mental illness (18). Our study suggests that the moral and ethical views of evaluators have the potential to influence their clinical-legal opinions about decision-making capacity with regard to assisted suicide. Those who believed that the practice is never morally acceptable advocated higher standards and more extensive review, even after psychiatrists who believed that such an evaluation itself is unethical were excluded. These forensic psychiatrists endorsed evaluation by more than one independent examiner followed by judicial or administrative review, which may be the most effective method for overcoming the bias in the evaluations, although with substantially increased burden to the patient.

Our study had several limitations. We do not know whether the 36% nonresponse rate reflected a response bias. The views of forensic psychologists, who also perform capacity evaluations, are not represented. Finally, the views of forensic psychiatrists may differ from those of general psychiatrists, who in practice may be asked to perform most evaluations of patients who request assisted suicide.

This study explored only one role of psychiatrists when patients request assisted suicide—determination of capacity to consent. The more traditional role of the psychiatrist is evaluation and treatment of the sources of suffering and anguish that may lead some persons to request hastened death. As one respondent to our survey wrote, “The focus of competence may distract from adequate attention and resources on the person and their circumstances...we may spend thousands of dollars on assessing competence and little in care directed to the day-to-day life and morale of the person.” Another respondent criticized the study, “What can psychiatrists do to improve the end-of-life care for the terminally ill? It seems to me we have a long way to go to help dying patients die with dignity in their final days. Perhaps we should focus our attention here and less on some of the abstractions touched on in the questionnaire.” Research and education must be focused not just on improving mental health professionals’ ability to evaluate competence in terminally ill persons desiring assisted suicide, but also their effectiveness in caring for dying patients.

Received Apr. 19, 1999; accepted Aug. 12, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry, Center for Ethics in Health Care, Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland; the Mental Health Division, Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Portland, Oregon; the Center for Forensic Services, Western State Hospital, Tacoma, Washington; the Veterans Affairs Outpatient Clinic, San Jose, California; and the Veterans Affairs Medical Center–West Los Angeles; and the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles. Address reprint requests to Dr. Ganzini, Mental Health Division (P-7-1DMH), Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center, P.O. Box 1034, Portland, OR 97207; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from the Veterans Affairs Merit Review Program. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Oregon Health Sciences University, University of California, or Department of Social and Health Services, State of Washington. The authors thank Mark Sullivan, M.D., Melinda Lee, M.D., and Joseph Bloom, M.D., for their comments.

|

|

|

|

1. Ganzini L, Lee MA: Psychiatry and assisted suicide in the United States. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:1824–1826Google Scholar

2. Baron CH, Bergstresser C, Brock DW, Cole GF, Dorfman NS, Johnson JA, Schnipper LE, Vorenberg J, Wanzer SH: A model state act to authorize and regulate physician-assisted suicide. Harv J Legislation 1996; 33:1–34Medline, Google Scholar

3. Quill TE, Cassel CK, Meier DE: Care of the hopelessly ill: proposed clinical criteria for physician-assisted suicide. N Engl J Med 1992; 327:1380–1384Google Scholar

4. Ganzini L, Fenn DS, Lee MA, Heintz RT, Bloom JD: Attitudes of Oregon psychiatrists toward physician-assisted suicide. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1469–1475Google Scholar

5. Lee MA, Nelson HD, Tilden VP, Ganzini L, Schmidt TA, Tolle SW: Legalizing assisted suicide—views of physicians in Oregon. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:310–315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Cohen JS, Fihn SD, Boyko EJ, Jonsen AR, Wood RW: Attitudes toward assisted suicide and euthanasia among physicians in Washington State. N Engl J Med 1994; 331:89–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Back AL, Wallace JI, Starks HE, Pearlman RA: Physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia in Washington State: patient requests and physician responses. JAMA 1996; 275:919–925Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Oregon Revised Statute 127.800–127.995Google Scholar

9. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 1988; 319:1635–1638Google Scholar

10. Ganzini L, Farrenkopf K: Mental health consultation and referral, in The Oregon Death With Dignity Act: A Guidebook for Health Care Providers. Edited by Haley K, Lee M. Portland, Ore, Task Force to Improve the Care of Terminally-Ill Oregonians, 1998, pp 30–32Google Scholar

11. Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG: Clinical Handbook of Psychiatry and the Law, 2nd ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1991Google Scholar

12. Lo B, Steinbrook R: Beyond the Cruzan case: the US Supreme Court and medical practice. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:895–901Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Cruzan v Director, Missouri Department of Health, 110 S Ct 2841, 1990Google Scholar

14. Grannum v Berard, 70 Wash 2d 304, 422 P 2d 1967:812, 4Google Scholar

15. Re Yetter, 62 Pa D & C2d 619, 623, Pa Com Pl 1973Google Scholar

16. Sullivan MD, Youngner SJ: Depression, competence, and the right to refuse lifesaving medical treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:971–978Link, Google Scholar

17. Van Der Maas PJ, Van Delden JJ, Pijnenborg L, Looman CW: Euthanasia and other medical decisions concerning the end of life. Lancet 1991; 338:669–674Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Sullivan M, Ganzini L, Youngner SJ: Should psychiatrists serve as gatekeepers for physician assisted suicide? Hastings Cent Rep 1998; 28:14–22Google Scholar