Barriers to the Treatment of Social Anxiety

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This article evaluates barriers to treatment reported by adults with social anxiety who participated in the 1996 National Anxiety Disorders Screening Day. METHOD: The background characteristics of screening day participants with symptoms of social anxiety (N=6,130) were compared with those of participants without social anxiety (N=4,507). Barriers to previous mental health treatment reported by participants with and without symptoms of social anxiety were compared. RESULTS: Social anxiety was strongly associated with functional impairment, feelings of social isolation, and suicidal ideation. Compared to participants without social anxiety, those with social anxiety were significantly more likely to report that financial barriers, uncertainty over where to go for help, and fear of what others might think or say prevented them from seeking treatment. However, they were significantly less likely to report they avoided treatment because they did not believe they had an anxiety disorder. Roughly one-third (N=1,400 of 3,682, 38.0%) of the participants with symptoms of social anxiety who were referred for further evaluation were specifically referred for an evaluation for social phobia. CONCLUSIONS: Social anxiety is associated with a distinct pattern of treatment barriers. Treatment access may be improved by building public awareness of locally available services, easing the psychological and financial burden of entering treatment, and increasing health care professionals’ awareness of its clinical significance.

Despite the availability of effective treatments for social phobia (1–3), most adults in the United States with social phobia do not receive mental health care for their symptoms (4, 5). In the well-known Epidemiological Catchment Area study (6), for example, more than two-thirds (72%) of community respondents with social phobia reported that they had never received outpatient mental health treatment. Among the major mental disorders, only drug and alcohol use disorders have lower rates of treatment (5). The public health challenge posed by untreated social phobia is underscored by mounting evidence linking social phobia to an increased risk of financial dependency, impaired role function, suicidal ideation, alcohol abuse, and a low rate of family formation (4, 5, 7–9).

Several studies have examined associations between sociodemographic characteristics and the treatment of mental health problems (10–12). People with social phobia who did not receive treatment were significantly younger, less educated, and less likely to be white than their counterparts who received treatment (5). While these statistical associations help identify population subgroups at increased risk of not receiving professional care, they provide little insight into the barriers that interfere with appropriate help seeking.

A more focused research strategy involves asking individuals why they did not seek treatment for their symptoms (13). One study, for example, reported that a substantial proportion of depressed adults who had not sought treatment believed they could handle the situation themselves (77%), treatment would not help (46%), or they could not afford treatment (36%) (14). A much smaller proportion did not seek treatment out of concern over how their friends and family might react (4%) (14).

The current article extends this research strategy to social anxiety. It draws on data collected from participants during the 1996 National Anxiety Disorders Screening Day. These data provide a unique opportunity to examine self-reported barriers to treatment in a large adult population with symptoms of social anxiety, defined as a fear of doing things in front of others, such as public speaking or eating and avoiding or feeling very uncomfortable in social situations. The specific goals of this study were to characterize screening day participants with symptoms of social anxiety, the barriers that prevented them from seeking treatment earlier, and the factors that affected professional recognition and referral for further evaluation of their symptoms.

National Anxiety Disorders Screening Day is a nonprofit educational program for individuals seeking information about anxiety disorders. It was initiated in 1994 and is designed to help participants determine if they have symptoms of common anxiety disorders. Sponsors include Freedom From Fear, the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, the Anxiety Disorders Association of America, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Mental Health Association, and the Obsessive-Compulsive Foundation. The program is conducted annually during the first week of May.

Activities related to the 1996 National Anxiety Disorders Screening Day occurred at 1,240 screening sites across the country. Screening sites were located in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. All sites were required to be under the direction of a licensed mental health professional. Before the screening day, an information package was sent to each site describing the recommended screening procedures and providing advice on local promotion of the screening day.

METHOD

Screening Procedures

On the screening day, participants were first asked to view an educational video featuring individuals with social phobia, four other common anxiety disorders, and major depression. After viewing the video, participants were invited to complete the screening questionnaire. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after the procedures had been fully explained. As participants completed the questionnaire, they were scheduled to meet with a health care professional to review their responses.

The health care professionals were instructed to spend 10–15 minutes meeting with each participant to review questionnaire responses and to decide if referral for further evaluation was recommended. Health care professionals were specifically instructed to inquire as to whether reported symptoms were distressing or resulted in functional impairment. The need for referral for further evaluation and the diagnostic focus of the referral was left to the professional’s clinical judgment.

Screening Questionnaire

The screening questionnaire included two social anxiety items with a 1-month reference period: “Were you afraid to do things in front of people, such as public speaking, eating, performing, teaching, or other things?,” and “Did you either avoid or feel very uncomfortable in situations involving people, such as parties, weddings, dating, dances, and other social events?” Throughout this article, participants who endorsed both of these screening items are referred to as having “social anxiety.” Participants who endorsed neither are referred to as having “no social anxiety.”

The screening questionnaire probed sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race or ethnicity, education, employment status, and geographic location), key psychiatric symptoms in the past month, mental health treatment history, and functional impairment. Functional impairment was indexed on a 6-point Likert scale for anxiety-related interference with the activities of daily life (1=“not at all” to 6=“almost all of the time”). Participants who endorsed number 6, “almost all of the time,” or number 5, “most of the time,” were considered to have functional impairment.

A checklist of eight common barriers to treatment was provided for participants who had never been previously treated for anxiety. Another question asked whether participants’ symptoms resembled those of the patient with social phobia in the video.

Diagnostic Substudy

Screening day participants from two sites (N=203) participated in an independent follow-up diagnostic interview conducted with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (15–17). Analyses of relationships between the endorsement of both social anxiety screening items and DSM-IV social phobia and between self-reported resemblance to a individual with social phobia seen on a video and diagnostic status are presented.

Analytic Strategy

Our primary objective was to examine the barriers to treatment associated with social anxiety. To provide a context for these analyses, we first compared the background characteristics of participants with and without social anxiety. Comparisons are presented with respect to sociodemographic composition, presence of seven psychiatric symptoms during the past month (thoughts of suicide, depressed mood, hopelessness, anhedonia, panic attack, persistent worry, and feelings of social isolation), functional impairment, self-reported resemblance of symptoms to those of an individual with social phobia on a video, mental health treatment history, referral disposition, and focus of the referral. We then compared the frequency of treatment barriers among the previously untreated subgroups and predictors of referral for the further evaluation of social anxiety. Finally, the subgroup of participants with social anxiety who reported that their symptoms resembled those of social phobia in the video were compared to their counterparts with social anxiety who did not report a resemblance.

The analysis was limited to participants who were at least 18 years of age, answered both social anxiety items, and skipped no more than four items on the screening questionnaire. These criteria reduced the study group size from 15,606 to 14,462.

Student’s t test is used for comparisons involving continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney U test for ordinal variables, and the chi-square test for categorical variables except when one or more expected values was 5 is less, in which case, Fisher’s exact test is used. Given the large study group size in the analyses involving ordinal variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was transformed into a normally distributed z statistic. All tests are two-tailed. To protect against the risk of type I error associated with multiple comparisons, alpha was set at 0.01.

Logistic regression was used to measure the associations of social anxiety with each of the psychiatric symptoms, functional impairment, and the service utilization variables controlling for age, sex, race or ethnicity, and the other psychiatric symptoms. Results were expressed as adjusted odds ratios with 99% confidence intervals (CIs). To test the reliability of the results, we randomly assigned each subject to an index or cross-validation group and ran the analyses first on the index and then the cross-validation group. Because the results were virtually identical, the results are not presented separately for the two groups.

RESULTS

Diagnostic Substudy

Forty-seven (23.2%) of the 203 participants in the diagnostic substudy met the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV criteria for social phobia. An affirmative response to both social anxiety screening items (“screen positive”) had a sensitivity of 0.64, a specificity of 0.85, a positive predictive value of 0.56, a negative predictive value of 0.89, and a total predictive value of 0.80 with respect to DSM-IV social phobia. Cohen’s kappa was 0.46.

Background Characteristics

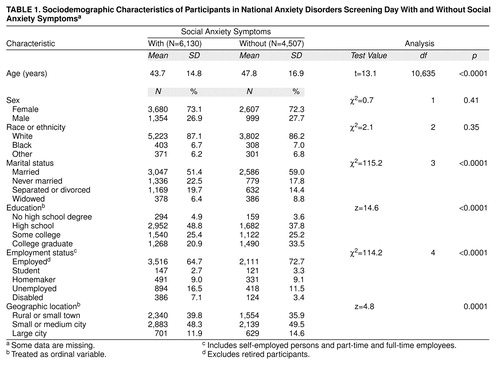

Symptoms of social anxiety were quite common. There were 6,130 (42.4%) of 14,462 participants who endorsed both social anxiety symptoms, 3,825 (26.4%) who endorsed one or the other of the symptoms, and 4,507 (31.2%) who endorsed neither symptom. As compared with participants without either social anxiety symptom, the group that reported having both symptoms was significantly younger in mean age and included a higher proportion of never married and separated or divorced individuals (table 1). Participants with both social anxiety symptoms also had a lower level of formal education and were proportionately more likely to be unemployed or disabled than their counterparts who had neither symptom of social anxiety (table 1). Those with social anxiety were also more likely to reside in a small town or rural area.

Clinical Characteristics

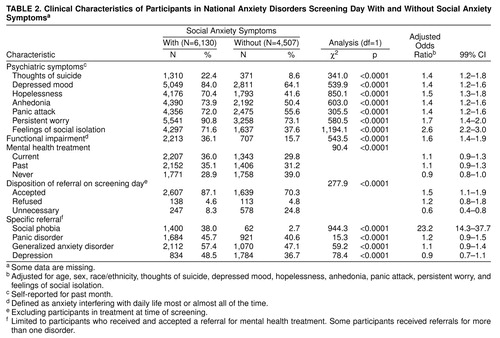

Social anxiety was positively associated with each of the other psychiatric symptoms, functional impairment, past and current mental health treatment, and referral for further evaluation (table 2). It was particularly strongly associated with feelings of social isolation. After controlling for the confounding effects of participant age, sex, race or ethnicity, and other psychiatric symptoms, having social anxiety was associated with a 2.6 times greater risk of having feelings of social isolation.

Almost one in four (N=1,310 of 5,849, 22.4%) of the individuals with social anxiety reported that they had thoughts of committing suicide in the past month. After adjustment for confounding demographic factors and psychiatric symptoms, having social anxiety was associated with a 1.4 times greater risk of having suicidal thoughts in the past month (table 2). Social anxiety was also associated with functional impairment; this association remained significant after controlling for the other psychiatric and demographic covariates.

Barriers to Treatment

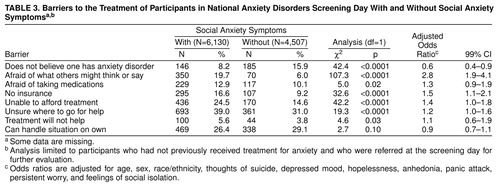

Participants who had never previously received mental health treatment were asked to indicate why they had not sought such care. Uncertainty over where to go for treatment was the most commonly reported barrier (table 3). Individuals with social anxiety were especially likely to report a fear of what others might think or say, a lack of insurance, an inability to afford treatment, and uncertainty over where to go for treatment as reasons they had not sought treatment in the past (table 3). In the multivariate model, having social anxiety was associated with a 2.8 times greater risk of being afraid of what others might think or say of seeking treatment.

Screening Day Disposition

A substantial minority of participants with social anxiety (N=1,400 of 3,682 who were referred for further evaluation, 38.0%) were specifically referred for an evaluation of social phobia (table 2). Although participants with social anxiety were more often referred for an evaluation of generalized anxiety disorder, depression, or panic disorder than for social phobia, only referral for an evaluation of social phobia remained statistically significant after adjusting for demographic covariates and co-occurring depressive and anxiety symptoms. Among participants with social anxiety, none of the sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race or ethnicity, education, employment status, or geographic location) was significantly related to referral for further evaluation of social phobia (data not shown).

Resemblance of Social Phobia Symptoms to Those in Video

Participants with social anxiety were far more likely than those without social anxiety to indicate that their symptoms resembled those of social phobia as portrayed on the educational video (N=2,662 of 6,130, 43.4%, versus N=107 of 4,507, 2.4%, respectively) (χ2=2,273.2, df=1, p<0.0001). Among participants with social anxiety, a reported resemblance to the symptoms of social phobia shown in the video was significantly related to functional impairment (N=1,156 of 2,662, 43.4%, versus N=1,057 of 3,468, 30.5%) (χ2=109.2, df=1, p<0.0001) and referral for evaluation of social phobia (N=979 of 2,662, 36.8%, versus N=846 of 3,468, 24.4%) (χ2=110.4, df=1, p<0.0001). These relationships remained statistically significant after controlling for demographic and other clinical characteristics: the adjusted odds ratio was 1.6 (99% CI=1.3–1.9) for functional impairment and 1.9 (99% CI=1.5–2.3) for referral for an evaluation of social phobia.

Data from the diagnostic substudy were used to examine the link between reported resemblance to the symptoms of social phobia in the video and DSM-IV diagnosis among participants with social anxiety. Because of a midstudy change in the screening form in the diagnostic substudy, information concerning resemblance to symptoms in the video was only available for 111 participants. This group included 10 participants with social anxiety who met the DSM-IV criteria for social phobia and nine with social anxiety who did not meet the DSM-IV criteria. Although nine of 10 participants with social anxiety who reported resemblance to the symptoms in the video met the criteria for social phobia, only four of nine with social anxiety who did not report a resemblance to symptoms in the video met the criteria for social phobia (p=0.008, Fisher’s exact test).

DISCUSSION

These results confirm and extend earlier research indicating that social anxiety is commonly associated with functional impairment and sometimes with suicidal ideation (4, 5, 7–9). Almost one in four adults with social anxiety reported suicidal ideation in the past month. Participants with social anxiety also often reported feelings of social isolation and pervasive anxiety-related interference in daily activities. The association of social anxiety with feelings of social isolation and with anxiety-related interference remained significant after controlling for other common anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Not knowing where to go for help was the most commonly reported barrier to mental health treatment among previously untreated participants with social anxiety on screening day. Because voluntary screening projects routinely provide information about local treatment resources, screening programs are likely to attract people who are seeking information about treatment services. It would be useful to know the extent to which a lack of information about available treatment services poses a barrier to treatment in the general population.

Many participants chose not to seek treatment earlier because they believed they could handle their symptoms by themselves. The decision to seek treatment may occur only when symptoms become sufficiently severe, disruptive, serious, or unpredictable that the individual can no longer manage or control them without assistance. Self-appraisal of illness severity is widely believed to influence the decision of whether to continue coping without assistance or to seek professional help (18).

Economic considerations, including lack of insurance and inability to afford treatment, were also common barriers to treatment. Consistent with previous research, we found a strong inverse association between social anxiety and socioeconomic status, as indicated by lower educational achievement and employment status in those with social anxiety (4, 19, 20). Mental health insurance plans with large deductibles or high first-dollar copayments may have a particularly adverse effect on the search for mental health services by this economically vulnerable group (21).

A fear of what others might think or say also frequently inhibited treatment seeking, particularly among participants with social anxiety. Socially anxious people are often ashamed of their symptoms and embarrassed to discuss them with friends or health care professionals. It is ironic that the very symptoms socially anxious individuals seek to relieve may interfere with their ability to seek treatment. Clinical administrators and health care professionals may help to address these concerns by guarding the privacy of individuals who seek mental health services or participate in mental health screening efforts.

Inadequate recognition of social anxiety by health care professionals may further hinder treatment delivery (22). Although the health care professionals conducting our screening were specifically focused on detecting anxiety disorders and had access to information confirming the presence of social anxiety symptoms, most participants with these symptoms were not referred for an assessment of social phobia. The low rate of referral for evaluation of social phobia may have been a result of the health care professionals’ unfamiliarity with social anxiety, an unawareness of the availability of effective treatments for social phobia, or the lack of appreciation of the relationship between social anxiety and social phobia.

Participant identification with the symptoms of social phobia in the video proved to discriminate powerfully between individuals with and without significant symptoms of social anxiety. Even within a population self-selected for anxiety, only about one in 40 people without social anxiety identified with the symptoms shown in this video. At the same time, the overwhelming majority of the small substudy group who reported social anxiety symptoms and identified with the symptoms of social phobia shown in the video met the formal DSM-IV criteria for social phobia.

Videos showing symptoms of psychiatric disorders represent a novel technique for identifying and classifying psychopathology that may have useful applications in large-scale epidemiological surveys and in clinical practice. After completing traditional symptom checklists or structured diagnostic interviews, subjects or patients could view brief videos of selected syndromes and then be asked to rate themselves on a scale of resemblance. At least for social anxiety, false positives are rare, and symptoms, together with identified resemblance, often indicate disorder.

Our analysis of social anxiety has some important limitations. First, self-selection into the screening program makes it difficult to generalize certain findings to either community or clinical populations. At the same time, however, screening day participants represent an important group of symptomatic individuals, many of whom are on the verge of entering or reentering treatment. Second, only about one-half of the individuals in the diagnostic substudy with social anxiety met the DSM-IV criteria for social phobia. Social anxiety, as we have defined it, is a substantially broader clinical construct than DSM-IV social phobia (23), and its precise relationship to the need for treatment remains uncertain. At the same time, the requirement that participants report anxiety in both performance and general interpersonal situations may have excluded several participants with the nongeneralized subtype of social phobia, so our findings may not apply to this subgroup. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the rate of functional impairment associated with endorsing only one social anxiety symptom (22.2%) was greater than that associated with having neither social anxiety symptom (15.7%) but was less than with associated with endorsing both symptoms (36.1%). Third, there is no perfectly satisfactory method for partialing out the effects of co-occurring anxiety and depressive symptoms while leaving the syndrome of social anxiety intact. To examine the unique association of social anxiety symptoms with measures of morbidity, we controlled for several co-occurring symptoms. However, because these symptoms may be true features of social anxiety, this approach risks losing or attenuating real relationships that may exist with social anxiety.

Several barriers may inhibit patients from coming in for treatment. An inability to afford treatment, an uncertainty over where to go for treatment, a fear of what others might think or say, and problems with clinical detection of social phobia each appear to play a role. Some barriers are easier to address than others. For example, whereas political and economic considerations perennially complicate efforts to expand third-party mental health coverage, a consensus may be much easier to achieve on the need to increase public awareness of the local availability of treatment services. Program directors should also work to ensure that their services can be accessed in a private and discreet manner that reduces patient fears of public scrutiny. At the same time, educational efforts should seek to increase mental health care professionals’ knowledge and skill in detecting clinically significant social anxiety.

Received Feb. 10, 1999; revision received Aug. 23, 1999; accepted Oct. 28, 1999. From the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University; and Freedom From Fear, Staten Island, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Olfson, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank Freedom From Fear for providing the data analyzed in this report.

|

|

|

1. Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, Pitts CD, Bushnell W, Gergel I: Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280:708–713Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneir FR, Holt CS, Welkowitz LA, Juster HR, Campeas R, Bruch MA, Cloitre M, Fallon B, Klein DF: Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia:12-week outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:1133–1142Google Scholar

3. Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Greist HJH, Jefferson JW, Mantle JM, Serlin RC: Sertraline for social phobia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1368–1371Google Scholar

4. Magee WJ, Eaton WW, Witchen HU, McGonalgle KA, Kessler RC: Agoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:159–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Liebowitz MR, Weissman MM: Social phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:282–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Robins LN, Regier DA: Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

7. Schneier FR, Heckelman LR, Garfinkel R, Campeas R, Fallon BA, Gitow A, Street L, Del Bene D, Liebowitz MR: Functional impairment in social phobia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:322–331Medline, Google Scholar

8. Liebowitz MR, Gorman JM, Fyer AJ, Klein DF: Social phobia: review of a neglected anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:729–736Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Amies PL, Gelder MG, Shaw PH: Social phobia: a comparative clinical study. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 142:174–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gallo JJ, Marino S, Ford D, Anthony JC: Filters on the pathway to mental health care, II: sociodemographic factors. Psychol Med 1995; 25:1149–1160Google Scholar

11. Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL, Freeman DH Jr, Weissman MM, Myers JK: Factors affecting the utilization of specialty and general medical mental health services. Med Care 1988; 26:9–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Dew MA, Dunn LO, Bromet E, Schulberg HC: Factors affecting help-seeking during depression in a community sample. J Affect Disord 1988; 14:223–234Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Greenfield SF, Reizes JM, Magruder KM, Muenz LR, Kopans B, Jacobs DG: Effectiveness of community-based screening for depression. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1391–1397Google Scholar

14. Blumenthal R, Endicott J: Barriers to seeking treatment for major depression. Depression and Anxiety 1996/1997; 4:273–278Google Scholar

15. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

17. Struening EL, Pittman J, Welkowitz L, Guardino M, Hellman F: Characteristics of Participants in the 1995–1996 National Anxiety Disorders Screening Day. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1998Google Scholar

18. Cameron L, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H: Symptom representation and affect as determinants of care seeking in a community-dwelling, adult sample population. Health Psychol 1993; 12:171–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Eaton WW, Dryman A, Weissman MM: Panic and phobia, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991, pp 155–179Google Scholar

20. Canino GJ, Bird HR, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, Bravo M, Martinez R, Sesman M, Guevara LM: The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in Puerto Rico. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:727–735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. McGuire TG: Financing and reimbursement for mental health services, in The Future of Mental Health Services Research: DHHS Publication ADM 89-1600. Edited by Taube CA, Mechanic D, Hohmann AA. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1989Google Scholar

22. Weiller E, Bisserbe JC, Boyer P, Lepine JP, Lecrubier Y: Social phobia in general health care: an unrecognised undertreated disabling disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:169–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Davidson JRT, Hughes DC, George LK, Blazer DG: The boundary of social phobia: exploring the threshold. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:975–983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar