Phenytoin as an Antimanic Anticonvulsant: A Controlled Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Phenytoin, a classical anticonvulsant, shares with antimanic anticonvulsants the property of blockade of voltage-activated sodium channels. The authors therefore planned a trial of phenytoin for mania. METHOD: Patients with either bipolar I disorder, manic type, or schizoaffective disorder, manic type, entered a 5-week, double-blind controlled trial of haloperidol plus phenytoin versus haloperidol plus placebo. Of 39 patients, 30 completed at least 3 weeks and 25 completed 5 weeks. RESULTS: Significantly more improvement was observed in the patients receiving phenytoin. Added improvement with phenytoin in scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and Clinical Global Impression was seen in the patients with bipolar mania but not those with schizoaffective mania. CONCLUSIONS: Blockade of voltage-activated sodium channels may be a common therapeutic mechanism of many anticonvulsants given for mania, and phenytoin may be a therapeutic option for some manic patients.

New anticonvulsants, such as lamotrigine and topiramate, have been investigated as possible antimanic compounds. While numerous biochemical properties have been found for carbamazepine, valproate, lamotrigine, and topiramate, all seem to share with phenytoin, the classical anticonvulsant, powerful inhibition of voltage-activated sodium channels (1). It thus seems of considerable theoretical importance to determine whether phenytoin is antimanic. Early uncontrolled studies showed improvement of mania with phenytoin (2). More recently, its cognitive side effects have been reassessed favorably (3). Because individual patients sometimes respond to one agent in a class and not to another, it could be of clinical as well as theoretical value to add phenytoin to the therapeutic armamentarium for bipolar illness. We therefore decided to conduct a trial of phenytoin for mania. On the basis of our previous study of carbamazepine (4), we used an add-on design with ongoing neuroleptic treatment.

METHOD

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences at Ben Gurion University of the Negev, and all patients gave informed written consent. Newly admitted patients could participate if they met the DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, manic type, or schizoaffective disorder, manic type (by consensus of two independent specialist psychiatrists), and had no serious physical illness. Generally, patients who had side effects from or inadequate response to mood stabilizers used in treatment of previous episodes were referred to the study: nine patients had nonresponse to lithium, two had nonresponse to carbamazepine, two had nonresponse to lithium and carbamazepine, one had nonresponse to lithium and valproate, one had lithium side effects, two had lithium side effects and nonresponse to carbamazepine, three were resistant to numerous previous treatments, and 10 wanted to try a new treatment.

Patients admitted to the study were started on haloperidol regimens at doses determined individually by the physicians. Trihexyphenidyl was available as necessary for extrapyramidal symptoms, and benzodiazepines were given as needed for sleep. Phenytoin or placebo was begun at a dose of 300 mg/day after completion of the screening physical and a laboratory examination. The daily dose was increased to 400 mg after 4 days, and the first blood level was determined on the third day after that. The patients received phenytoin or identical capsules of placebo as assigned by the control psychiatrist (R.H.B.) according to random order; the bipolar manic and schizoaffective manic patients were randomized separately.

No washout of previous medication was required, and eight patients had received outpatient treatment with low doses of neuroleptics before admission for acute mania. Three of these eight patients, all with schizoaffective disorder, were admitted not from the community but from a chronic long-stay domicile ward and received low-dose neuroleptics before entering the acute-treatment ward and the study. Phenytoin treatment was begun for all patients within 5 days of the onset of haloperidol treatment. Weekly ratings by a psychiatrist blind to the study drug were conducted by using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), the Young Mania Rating Scale (5), and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI). Blood was drawn weekly for measurement of phenytoin levels, and the results were reported to the control psychiatrist, who created dummy levels for the placebo patients and reported the results to the treating physicians, who adjusted the doses of phenytoin or placebo accordingly.

Over 1 year, 39 patients entered the study; 30 completed at least 3 weeks, and 25 completed 5 weeks. Patients completing at least 3 weeks were included in the data analysis, with the last value carried forward. Of these 30 patients, 18 had schizoaffective disorder, manic type, and 12 had bipolar disorder, manic type. Of the nine patients who dropped out before 3 weeks, one experienced phenytoin toxicity (gait instability, blood level=26 µg/ml), three refused to continue in the study (one taking phenytoin and two taking placebo), three (taking phenytoin) had exacerbations after 2 weeks, one (taking phenytoin) left after his brother’s suicide, and one (taking placebo) violated the protocol with nonstudy medication. Completing 5 weeks were six bipolar manic patients taking phenytoin, four bipolar manic patients taking placebo, seven schizoaffective manic patients taking phenytoin, and eight schizoaffective manic patients taking placebo.

RESULTS

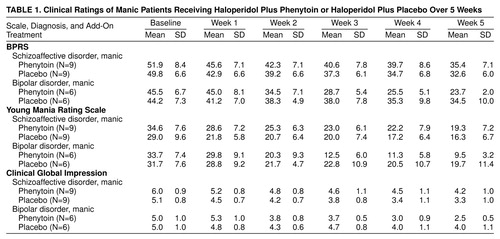

Table 1 contains scores on the BPRS, Young Mania Rating Scale, and CGI. The analyses of the ratings (Greenhouse-Geisser corrected) were three-way multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) for diagnosis, treatment, and time, with covariance for baseline score.

For the BPRS scores the MANCOVA showed a significant three-way interaction of diagnosis, treatment, and time (F=5.09, df=2.3, 60.6, p=0.006), with a significant two-way interaction between treatment and time (F=3.83, df=2.3, 60.6, p=0.02) and a significant two-way interaction between treatment and diagnosis (F=4.42, df=1, 25, p<0.05). For the bipolar manic patients there was a significant two-way interaction of treatment and time (F=5.61, df=1.7, 17.4, p<0.02). The differences between phenytoin and placebo were significant (according to Tukey’s honest significant difference post hoc test) only for the bipolar manic patients at week 3 (p=0.03), week 4 (p=0.02), and week 5 (p=0.01). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the schizoaffective manic patients was not significant (F=0.31).

For the CGI ratings there was also a significant three-way interaction of diagnosis, treatment, and time (F=5.64, df=2.6, 68.2, p=0.003), with a significant two-way interaction between treatment and time (F=4.03, df=2.6, 68.2, p=0.01), a significant two-way interaction between diagnosis and time (F=3.64, df=2.6, 68.2, p=0.02), and a significant two-way interaction between treatment and diagnosis (F=4.24, df=1, 25, p=0.05). For the bipolar manic patients there was a significant two-way interaction of treatment and time (F=6.35, df=1.9, 18.7, p=0.01). The differences between phenytoin and placebo were significant only for the bipolar manic patients at week 5 (Tukey’s honest significant difference post hoc test, p=0.001). For the schizoaffective manic patients a two-way ANOVA for the interaction of treatment and time was not significant (F=0.63).

For the scores on the Young Mania Rating Scale there was not a significant three-way interaction of diagnosis, treatment, and time. There was a significant two-way interaction between treatment and time for all patients (F=4.65, df=2.5, 65.7, p=0.008) and a significant two-way interaction between diagnosis and time (F=4.68, df=2.5, 65.7, p=0.008).

The mean daily haloperidol doses did not significantly differ between the patients taking phenytoin and placebo at any point in the study and rose from 14.4 mg (SD=7.6) in week 1 to 16.8 mg (SD=7.5) in week 5. The daily numbers of capsules of placebo and phenytoin were not significantly different at any week, reaching a mean of 5.0 capsules at week 5. The mean phenytoin levels were 9.4 µg/ml (SD=6.1) at week 1, 14.1 µg/ml (SD=6.2) at week 2, 16.0 µg/ml (SD=7.4) at week 3, 19.1 µg/ml (SD=8.4) at week 4, and 21.4 µg/ml (SD=9.9) at week 5.

One young woman developed tachycardia at 500 mg/day of phenytoin at week 4 and was dropped from the study. One older man developed nystagmus in week 1, which responded to a lowering of his dose. The patients showed a surprising absence of somnolence or lethargy, even at a mean phenytoin blood level of 21.4 µg/ml in week 5.

DISCUSSION

The magnitude of the effect for phenytoin-related improvement in the bipolar manic and schizoaffective manic patients compares with similar figures for carbamazepine (4) studied with a similar acute-treatment add-on design. This supports the concept that all anticonvulsants that block voltage-activated sodium channels (1) are potential antimanic compounds.

The present study is limited by the small size and diagnostic variability. The fact that all patients received haloperidol makes it more difficult to determine the nature of the phenytoin effect. Phenytoin has been reported to reduce haloperidol blood levels (6), and it is possible that the effect of phenytoin would be more marked in a placebo-controlled monotherapy design. The present study provides no information on whether phenytoin has prophylactic value against mania or depression in bipolar disorder.

The ratings with the BPRS and CGI seemed to show that the benefit of phenytoin was limited to the bipolar manic patients. This conclusion should be interpreted cautiously, since the Young Mania Rating Scale did not make this distinction. Also, the schizoaffective group included more patients who had shown nonresponse to previous treatment.

Long-term prophylactic studies of phenytoin in bipolar disorder will need to take into account the danger of gingival hyperplasia, leukopenia, or anemia and the danger of toxicity due to nonlinear pharmacokinetics. However, phenytoin is a first-line anticonvulsant in epilepsy, and its potential in psychiatry should not be ignored.

Received May 4, 1999; revision received Aug. 10, 1999; accepted Sept. 3, 1999. From the Stanley Center for Bipolar Research, Ministry of Health Mental Health Center, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beersheva, Israel; and the Barzilai Medical Center, Ashkelon, Israel. Address reprint requests to Dr. Belmaker, Beersheva Mental Health Center, P.O. Box 4600, Beersheva, Israel; [email protected] (e-mail).

|

1. Dichter MA: Mechanisms of action of new antiepileptic drugs. Adv Neurol 1998; 76:1–9Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kalinowsky LB, Putnam TJ: Attempts at treatment of schizophrenia and other non-epileptic psychoses with Dilantin. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1943; 49:414–420Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Devinsky O: Cognitive and behavioral effects of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia 1995; 36(suppl 2):S46–S65Google Scholar

4. Klein E, Bental E, Lerer B, Belmaker RH: Carbamazepine and haloperidol versus placebo and haloperidol in excited psychoses: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:165–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429–435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Linnoila M, Viukari M, Vaisanen K, Auvinen J: Effect of anticonvulsants on plasma haloperidol and thioridazine levels. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137:819–821Link, Google Scholar