Somatization in an Immigrant Population in Israel: A Community Survey of Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Help-Seeking Behavior

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Knowledge about the frequency, severity, and risk factors of somatization (somatic manifestations of psychological distress) among immigrants is limited. The authors examined somatic distress in an immigrant population in Israel, explored its relationship with psychological distress symptoms and health-care-seeking behavior, and determined its correlation with the length of residence in Israel. METHOD: Two reliable and validated self-report questionnaires, the Brief Symptom Inventory and the Demographic Psychosocial Inventory, were administered in a cross-sectional community survey of 966 Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union who had arrived in Israel within the previous 30 months. RESULTS: The 6-month prevalence rate for somatization was 21.9% and for psychological distress, 55.3%. The current rate of co-occurrence of somatization and psychological distress was 20.4%. The most common physical complaints were heart or chest pain, feelings of weakness in different parts of the body, and nausea. Somatization was positively correlated with the intensity of psychological distress and with help-seeking behavior during the 6 months preceding the survey. Women reported significantly more somatic and other distress symptoms than men. Older and divorced or widowed individuals were more likely to meet the criteria for somatization. Within the first 30 months after resettlement, longer length of residence was associated with higher levels of somatization symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: Somatization is a prevalent problem among individuals in cross-cultural transition and is associated with psychological distress; demographic characteristics such as gender, age, marital status, and duration of immigration; self-reported health problems; and immigrants’ help-seeking behavior.

In the last decade, there has been increased interest in the mental health of immigrants from the former Soviet Union to the United States and Israel (1–6). Despite these studies, knowledge about the frequency, severity, and risk factors of somatic manifestations of psychological distress in this population is limited.

People suffering from psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and personality disorders, as well as those with DSM-IV somatization disorder, may exhibit somatic symptoms. Somatization has been broadly defined as the presentation of one or more medically unexplained somatic symptoms that does not fulfill DSM-IV criteria for somatization disorder or other somatoform disorders (7).

Epidemiological studies’ estimates of the prevalence of somatization in the general population have ranged from 4% to 20%, depending on the diagnostic criteria used in the study (8, 9). DSM-IV somatization disorder is a rare diagnosis in the general population (10) but seems more frequent in primary care settings (11, 12). Recently, a large international study that used data from 15 primary care centers in 14 countries found that the overall prevalence rate of ICD-10 somatization disorder was 2.8% and that the overall prevalence rate for somatization, as measured by the Somatic Symptom Index, was 19.7% (13).

There is strong evidence that somatization is related to substantial emotional distress expressing underlying anxiety, depression, and adjustment disorders (7, 10, 12). Using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, a population-based survey of more than 18,000 residents of five U.S. communities, Simon and Von Korff (14) found that current psychological symptoms were reported by 63% of individuals who also reported five or more somatic symptoms, compared with 7% of those who reported no somatic symptoms.

Previous studies have suggested that the somatization phenomenon is influenced by demographic variables, such as gender, age, marital status, low educational and economic levels, rural residence, and minority ethnicity (10, 11, 15). Generally, women are more likely to show evidence of somatization than men, but these findings are inconsistent (16). Although some researchers have not found gender differences in somatization patterns (17), others have reported a twofold increase in risk of somatization among women compared with men (18). In one study that used regression analysis, gender had no significant effect on the level of somatic symptoms when the analysis controlled for the effect of emotional distress (19). Low social support has been demonstrated to increase rates of somatization and utilization of medical care among elderly and divorced or separated and widowed persons (20).

Studies have shown that immigrants all over the world experience significantly more stressful life events and psychological distress than members of native populations and therefore have a higher risk of somatization. However, few researchers have examined the somatic presentation of distress among immigrants. Kohn et al. (2) reported elevated levels of demoralization with concomitant increases in depression and somatization in 55 older Jewish-Soviet immigrants to Chicago. Pang and Lee (21) estimated the current prevalence of somatization disorder in elderly Korean immigrants in the United States to be 7.3% and the co-occurrence of the disorder with major depression to be 33.3%. Handelman and Yeo (22) evaluated the frequency of somatic symptoms in 76 elderly Cambodian refugees and found that headache and chest complaints were the most common symptoms (58% and 41%, respectively). More than half of all respondents interpreted their symptoms to be the result of sadness, grief, and anxiety. The small clinically based sample and the older age of the participants compromised the results of these studies. Although these studies and other studies (23, 24) have found that immigrants are prone to communicate emotional distress in terms of physical complaints, to our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the prevalence and risk factors of somatization in a large community sample of recent immigrants.

The current mass immigration from the former Soviet Union to Israel (nearly 800,000 immigrants between 1989 and 1999) has offered a unique research opportunity. In the study reported here, we investigated 1) the prevalence of somatic symptoms in an immigrant population, 2) the effect of the length of residence in the new location on somatization, 3) the relationship between somatic and psychological presentations of distress, 4) demographic correlates of bodily symptoms, and 5) the effect of somatization on health-care-seeking behavior.

We hypothesized that 1) somatization is more frequent in distressed than in nondistressed immigrants, 2) bodily symptoms are presented more frequently in women and in older and unmarried individuals than in men and in younger and married subjects, and 3) somatizing immigrants are more likely to seek help for their health problems from family doctors than from mental health professionals.

METHOD

This study is part of the Immigrant Psychological Distress Project initiated in 1991 in Israel. At the time this report was prepared, the project’s database contained community survey data for 3,713 subjects, age 11 years and older, who resettled in Israel from the former Soviet Union between 1989 and 1997. The study design, sampling, sociodemographic profile of subjects, background, and some clinical findings from the diverse sections of the Immigrant Psychological Distress Project have been reported in detail elsewhere (3, 4, 6, 25, 26).

In the study reported here, data for 966 immigrants (397 men and 569 women) were drawn from the project’s database according to two inclusion criteria: age 18 and older, and the availability of distress and somatization measures. These respondents, who constituted a convenience study group, had been recruited from typical immigrant gathering places, including professional retraining classes, Hebrew language instruction classes, and temporary accommodations at hostels and social services. Data were obtained from approximately 75% of the immigrants present at the time of data collection at each setting. Overall, 10% of the immigrants approached refused to participate. A comparison of participants with nonparticipants showed no significant differences in any of the demographic characteristics surveyed. Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

For the 966 immigrants included in the analyses reported here, the male-female ratio was 1:1.4. The mean age was 39.3 years (SD=12.9; range=18–87). About 54% (N=521) had immigrated within 12 months of the study, 42% (N=406) within 1 to 2 years, and 4% (N=39) within 25 to 30 months. The mean length of time in Israel was 12.5 months (SD=7.8; range=3–30). A total of 67% (N=647) were married, 13% (N=124) were single, 19% (N=186) were divorced or widowed, and the marital status of 1% (N=10) was unknown. About 79% (N=763) were university graduates, 13% (N=129) had completed vocational training, 5% (N=48) had a high school diploma, and 2% (N=21) had a grade school education.

All participants completed the Russian language versions of two self-report questionnaires, the Brief Symptom Inventory and the Demographic Psychosocial Inventory. Participants were asked to consider conditions over the preceding 6 months in responding to the questionnaires.

The Brief Symptom Inventory (27) is a 53-item version of the well-known Hopkins Symptom Checklist-90. Responses are scored on a 0–4-point scale, with higher mean scores indicating greater levels of psychological distress (Global Severity Index) and of nine symptom dimensions: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. We determined cases of distress by using Global Severity Index thresholds (27); Global Severity Index values equal to or greater than 0.42 for men and 0.78 for women indicated distress. For the study group (N=966), Cronbach’s alpha for the Global Severity Index was 0.91.

The Brief Symptom Inventory somatization scale reflects distress arising from perceptions of bodily dysfunctions. Its seven items focus on faintness or dizziness, heart or chest pain, nausea or upset stomach, shortness of breath, hot or cold spells, numbness or tingling, and feeling weakness in parts of the body. Cronbach’s alpha for the somatization rate was 0.89 for the study group.

To compare our data with results of previous studies, we used three diagnostic criteria for somatization. The overall Brief Symptom Inventory somatization criterion yielded mean raw scores on the somatization scale of 0.70 for men and 0.91 for women (corresponding T score=63 or higher), exhibiting the presence of somatization according to the thresholds elaborated by Derogatis and Spencer (27). The two other criteria for somatization, adapted from previous studies (11, 19, 28), were based on a simple count of the overall number of somatic symptoms independent of modality or organ system specificity. The first, the Somatic Symptom Index 4/6 (11), requires four somatic symptoms for male subjects and six such symptoms for female subjects. The second, Somatic Symptom Index 5/5 (11), delineates somatization in terms of the number of somatic symptoms with a threshold at five symptoms for subjects of both sexes.

The Demographic Psychosocial Inventory was designed to provide a standardized measure of psychosocial variables among Russian immigrants to Israel (29). It consists of 84 self-report questions, including 10 scales and three general indices. Responses are scored on a 0–4-point scale, with higher mean scores indicating a greater degree of addressed difficulties. Four health-related dimensions of the Demographic Psychosocial Inventory were used in this study: 1) current health problems (one item), 2) health-seeking intentions (15 items, Cronbach’s alpha=0.79), which asks if the respondent is in need of help from any of 15 different health care professionals, 3) help-seeking behavior (five items, Cronbach’s alpha=0.44), which ask if the respondent applied for help from one of five different health care specialists (family doctor, neurologist, psychologist, psychiatrist, and social worker), and 4) the health index (21 items, Cronbach’s alpha=0.81), which is the sum of the scores for the other three dimensions divided by the number of scales. Reliability and validity tests of the Demographic Psychosocial Inventory had satisfactory results.

All analyses were performed by using the Number Cruncher Statistical System (NCSS-2000) (NCSS Statistical Software, Kaysville, Utah). Differences in means were tested with two-tailed t tests. For comparisons of proportions, the chi-square test with Yates’s correction for continuity was calculated. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each of seven somatic symptoms reported by immigrants versus the Brief Symptom Inventory normative nonpatient sample (27). Pearson product moment correlations between the Brief Symptom Inventory symptoms and Demographic Psychosocial Inventory health subscales were computed. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for investigating the main effects of gender, age, marital status, and length of residence in Israel on the variation in the psychological distress and somatization scores. For all analyses, the level of statistical significance was defined as an alpha less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Prevalence of Somatization

Of 966 respondents, 212 met the Brief Symptom Inventory criterion for somatization and 754 did not. Thus, the 6-month prevalence rate of somatization as measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory for the entire group was 21.9% (95% CI=19.3%–24.5%). The corresponding rates as measured by the Somatic Symptom Index were significantly lower: 14.9% (N=144) for Somatic Symptom Index 5/5 (χ2=15.4, df=1, p<0.001) and 13.8% (N=133) for Somatic Symptom Index 4/6 (χ2=21.5, df=1, p<0.001). Use of the Brief Symptom Inventory somatization criterion showed no significant gender differences in the somatization prevalence rate.

Somatization and Length of Residence

Two-way ANOVA was used to assess the main effect of length of residence in Israel (by gender) on the Brief Symptom Inventory psychological distress and somatization scores. Length of residence was defined as the time between the date of resettlement and the date of participation in the study. The analyses were conducted for four groups of subjects with different lengths of residence: 6 months or less (N=209), 7–12 months (N=312), 13–18 months (N=288), and 19–30 months (N=157). Mean scores on the Brief Symptom Inventory somatization dimension for the four subgroups according to gender were: 0.41 (SD=0.58), 0.28 (SD=0.35), 0.36 (SD=0.42), and 0.63 (SD=0.74), respectively, for the men; and 0.57 (SD=0.63), 0.51 (SD=0.54), 0.48 (SD=0.48), and 1.13 (SD=1.11), respectively, for the women. All three ANOVAs for somatization were significant: F=25.0, df=1, 963, p<0.0001, for gender; F=19.9, df=3, 963, p<0.0001, for length of residence; and F=2.9, df=3, 963, p=0.04, for the gender-by-time interaction. With regard to the Global Severity Index distress scores, main effects were revealed for gender (F=7.9, df=1, 963, p<0.005) and length of residence (F=11.6, df=3, 963, p<0.0001) but not for their interaction (F=0.7, df=3, 963, p=0.55). The results suggest that for the first 2.5 years after resettlement, the more time elapsed, the higher the levels of psychological distress and somatization for both male and female subjects.

Number of Somatic Symptoms

The distribution of the respondents and their Global Severity Index mean scores according to the number of reported somatic symptoms was computed. A total of 22.7% of respondents (N=219) reported no somatic symptoms, although 3.3% (N=32) endorsed all seven of the Brief Symptom Inventory somatic symptoms. Concerning the overall number of physical symptoms, the female-male ratio increased from 0.86 for those with one symptom (N=101 for women and N=118 for men) to 3.2 for those with five symptoms (N=45 for women and N=14 for men). Most somatizing subjects (83.5%; N=177 of 212) reported four or more somatic symptoms. Somatizing women (N=124) tended to have a greater mean number of somatic symptoms (mean=5.32, SD=1.2) than somatizing men (N=88) (mean=4.33, SD=1.5) (t=5.1, df=210, p<0.001).

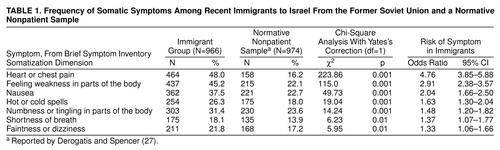

Frequency of Somatic Symptoms

Table 1 compares the frequency of Brief Symptom Inventory somatic symptoms among the immigrants with the frequency in a normative sample studied by Derogatis and Spencer (27). The immigrants endorsed all somatic symptoms significantly more often than the nonpatient comparison subjects. The likelihood (odds ratios) for immigrants to have the seven symptoms ranged from 1.33 to 4.76, compared with the normative nonpatient sample. The most common symptoms reported by the immigrant group were heart or chest pain, feeling weakness in parts of the body, and nausea. Numbness in parts of the body, nausea, and feelings of weakness were the most common symptoms in the comparison subjects.

Distress and Somatization

As expected, immigrants with psychological distress scored 10.5 times higher on the Brief Symptom Inventory somatization rate (N=197 of 534; 36.9%) than nondistressed immigrants (N=15 of 432; 3.5%) (χ2=153.8, df=1, p<0.0001). The correlation between levels of distress and somatization was similar for women and men (r=0.6), but distressed women endorsed all somatic complaints significantly more often than distressed men (N=113 of 261, 43.3%; and N=84 of 273, 30.8%, respectively) (χ2=8.5, df=1, p<0.005). No significant gender differences in the Brief Symptom Inventory somatization rate were found among nondistressed subjects (3.2% for male subjects and 3.6% for female subjects).

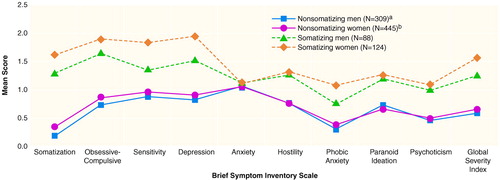

The Brief Symptom Inventory psychological symptom profiles of somatizing and nonsomatizing respondents were compared for each gender separately (figure 1). The overall profiles of somatizing subjects were significantly higher than those of nonsomatizing subjects (p<0.001). Patterns of psychological symptoms and symptom severity differed for men and women. In both groups, women had significantly higher mean scores than men on the Global Severity Index and on the somatization and phobic anxiety scales (t=3.5, df=964, p<0.001; t=4.8, df=964, p<0.001; and t=3.7, df=964, p<0.001, respectively). In the somatizing group, somatization (t=3.6, df=210, p<0.001), interpersonal sensitivity (t=3.9, df=210, p<0.001), and depression (t=3.2, df=210, p<0.01) scale scores were significantly higher for women than men. In the nonsomatizing group, somatization (t=9.1, df=752, p<0.001), obsessive-compulsive (t=2.8, df=752, p<0.01), anxiety (t=2.0, df=752, p<0.05), and phobic anxiety (t=2.9, df=752, p<0.01) scale scores were significantly higher for women than men. Anxiety was the only symptom for which a gender difference was found in the nonsomatizing group but not in the somatizing group; the women in the nonsomatizing group had significantly higher anxiety scale scores than the men (t=5.2, df=395, p<0.001).

Demographic Risk Factors

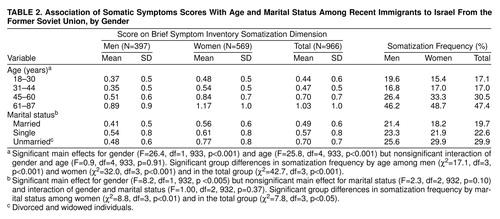

Association between mean somatization scores, proportions of somatizing subjects, and demographic characteristics were examined (table 2). Overall, somatizing immigrants were older than their nonsomatizing counterparts (mean=44.6 years, SD=15.5, versus 37.8 years, SD=11.7) (t=5.9, df=964, p<0.001).

Post hoc multiple comparison tests showed that the mean somatization score for subjects aged 31–44 years did not significantly differ from the mean score for the immediately younger cohort (aged 18–30). In contrast, mean somatization severity scores gradually and significantly increased with age: mean=0.47, SD=0.51 for the 31–44 year age group, mean=0.70, SD=0.68 for the 45–60 year age group (two-tailed t test=4.19, df=641, p<0.0001), and mean=1.03, SD=1.04 for the 61–87 year age group (t=2.5, df=253, p=0.01). Correspondingly, respondents who were 45 years and older tended to have a higher risk of somatization than those aged 18–44 (see frequency section, table 2).

ANOVA confirmed a significant relationship between somatization and female gender (F=21.6, df=1, 966, p<0.0001) and marital status (F=8.4, df=2, 966, p<0.001). Overall, women, compared with men, and divorced and widowed respondents, compared with married and single respondents, exhibited higher levels of somatization as well as greater proportions of somatizing cases.

Somatization and Health-Care-Seeking Behavior

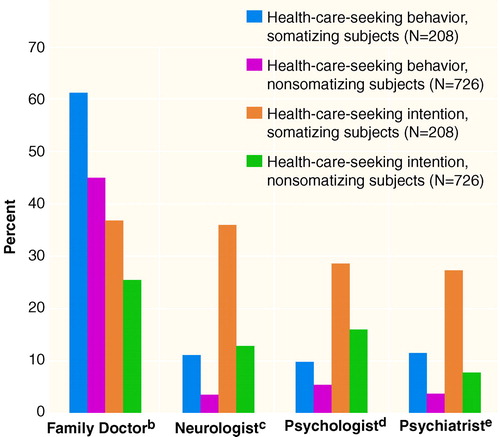

To examine the effects of somatization on self-reported health status and health-care-seeking behavior, correlations between ratings of these variables were computed. Both self-reported poor health and health-care-seeking intention/behavior correlated positively with the Brief Symptom Inventory somatization scores (r=0.34–0.38), but not with the depression and anxiety scores. Somatizing and nonsomatizing subjects were compared on health-care-seeking intentions and actual appointments with four medical specialists (family doctor, neurologist, psychologist, and psychiatrist) in the 6 months preceding the survey. Figure 2 illustrates the significant differences in these variables between the two groups. As expected, somatizing immigrants were more likely than nonsomatizing immigrants to have both health-care-seeking intentions and actual contacts with all health care providers. Among somatizing subjects, a disproportionately higher proportion (60.4%; N=128) sought help from family doctors, compared with the proportions who turned to mental health specialists, such as neurologists (10.4%; N=22), psychologists (9.0%; N=19), and psychiatrists (10.4%; N=22). Although 34.9% of the somatizing subjects (N=74) reported a desire seek the help of mental health professionals, only 10% (N=21) actually approached a neurologist, psychologist, or psychiatrist during the 6 months preceding the survey.

DISCUSSION

Although psychological distress has been observed to be higher among immigrants than among native populations, little is known about the prevalence, number, and severity of somatic symptoms associated with psychological distress in the immigrant population. The findings presented here, based on a unique large database representing Russian-born Jewish immigrants to Israel, extend our knowledge in the field.

All hypotheses of the study relating somatization to sociodemographic and psychosocial factors were confirmed. First, somatization was more frequent in distressed than in nondistressed immigrants. Second, physical symptoms appeared more frequently in women and in older and unmarried individuals than in men and in younger and married subjects. Finally, somatizing immigrants more frequently sought help from family doctors than from mental health professionals.

The prevalence rate of somatization in this study was higher than rates previously reported in the general population. Comparisons are difficult, however, because different diagnostic criteria and instruments were used in previous studies. Nevertheless, the prevalence rate of somatization based on the Brief Symptom Inventory criterion in our study (21.9%) is very similar to the rates of 19.7% reported in a WHO study in primary care settings in 14 countries (15) and of 22% reported in a large-scale U.S. study in primary care by Escobar et al. (30). The previous rates were obtained by using the Somatic Symptom Index, based on a simple count of somatic symptoms. In our study, use of an abridged version of the same somatization criterion (Somatic Symptom Index 4/6) yielded a prevalence rate of 13.8%, lower than the Brief Symptom Inventory somatization rate. We conclude that if the Brief Symptom Inventory criterion is reliable, our study population exhibited a somatization rate higher than in the general population but comparable to the level in primary care settings.

Heart or chest pain was the most common somatic presentation (48%) in this study. “Heart distress” was reported by the immigrants three times as often as in the Brief Symptom Inventory normative nonpatient sample. One explanation could be a culture-related somatic idiom of distress shared by Jewish immigrants to Israel. Throughout the Middle East, references to the heart are commonly understood not just as potential signs of illness but as natural metaphors for a range of emotions expressing personal and social concerns primarily related to loss and grief (31, 32). Alternatively, heart/chest complaints among Russian Israelis could be explained as a reflection of concern about actual heart disease. An elevated rate of ischemic heart disease in a study of 397 Russian immigrants in primary care clinics in Israel during 1990–1991 indirectly confirmed this assumption (33). That study found heart disease rates of 18.8% for male and 9.5% for female immigrants, compared with 5.8% and 4.0%, respectively, for the nonimmigrant population. It should be taken into account, however, that in the general population as few as 10% of primary care patients presenting with heart or chest pain were found to have an organic diagnosis (34, 35). A careful analysis of this type of somatic presentation requires more specific investigation in the future.

Our findings that somatization highly correlates with psychological distress confirm previous reports (2, 36). The proportion of somatizing subjects among distressed immigrants was 10.5 times greater than that among nondistressed immigrants. Our data also showed that an increase in the number of somatic symptoms actually reflects greater severity of both psychological and somatic distress.

Overall, the profile of psychological symptoms was markedly higher among somatizing than nonsomatizing subjects, but the profiles of both groups converged in level of anxiety (figure 1). In our study group, somatic symptoms seemed to substitute for anxiety, as described in psychodynamic theories concerning conversion disorder. This finding contradicts previous clinical studies that suggested a high comorbidity of anxiety and somatization disorders (13, 36). The finding that general anxiety is not associated with somatic distress suggests the need for a more differentiated approach toward clinical assessment of the potential for somatization among patients with a variety of anxiety disorders.

The role of depressive symptoms in the occurrence of somatization was evaluated differently in previous studies. Although many authors have related somatization to depressive complaints (19, 36, 37), others have not found a specific association (18). Our findings support Fink’s conclusion (38) that somatization is associated with a broad spectrum of heterogeneous psychological symptoms, not only with depressive symptoms. In particular, obsessive-compulsive symptoms and phobic anxiety were highly correlated with somatization. Thus, our results confirm the view (39) that somatization should be regarded as a basic mechanism by which individuals respond to stress rather than as an idiopathic disease in its own right.

Our finding that female gender is a factor predisposing the development of somatization is consistent with previous research (2, 40, 41). It should be kept in mind that in most studies findings of higher levels of almost all symptoms of psychological distress in women were independent of the symptom measure, response format, time frame, and the population under study (40). The Brief Symptom Inventory somatization measure is not an exception to this trend.

Our finding of substantially increased somatization scores for older individuals and immigrants without spouses is consistent with previous studies. Factors reflecting social isolation have been shown to be associated with somatization and increased rates of medical utilization. A possible explanation is that these persons turn to health care providers as an auxiliary social support system in times of stress (15, 38).

The relationship between increased levels of distress and help-seeking behavior was established in previous studies of immigrants (2, 3). Our findings, however, demonstrate that significantly more somatizing immigrants intended to seek medical care than actually did. This predominance of intention over actual behavior existed in relation to all health care providers but more so in relation to psychiatrists and psychologists than to family doctors. This finding clearly demonstrates apprehension related to the stigma of psychiatric illness. Of all dimensions of psychological distress, only somatization exhibited a significant positive correlation with self-reported health problems and health-care-seeking intentions and behaviors. Thus, there is evidence that the somatic component of psychological distress (not depression or anxiety symptoms) actually motivates help-seeking behavior. This finding confirms a common pattern of increased use of health care services by somatizing patients (42, 43).

Certain limitations of this study should be noted. Some immigrants we considered to be somatizing subjects may or may not have had some degree of associated physical disease. Unfortunately, we were not able to verify these assumptions at this stage of the study. Future investigations designed to overcome these limitations are needed to further understand the contribution of somatic symptoms to psychological distress.

Received Jan. 13, 1999; revisions received May 13 and Aug. 16, 1999; accepted Sept. 6, 1999From the Institute for Psychiatric Studies, Sha’ar Menashe Mental Health Center; the Department of Psychiatry, Hebrew University–Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem; and the Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, Technion, Haifa, Israel. Reprints are not available. Address correspondence to Dr. Ritsner, Mobile Post Hefer 38814, Sha’ar Menashe Mental Health Center, Hadera, Israel; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by the Ministry of Immigrant Absorption, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Science (Israel). The authors thank A. Factourovich, K. Levin, and A. Segal for their assistance in data collection.

|

|

FIGURE 1. Mean Scores on Psychological Symptom Scales of Somatizing and Nonsomatizing Subjects Recently Immigrated to Israel From the Former Soviet Union

aSignificantly different from somatizing men in scores on the Global Severity Index and on all scales except the anxiety scale (t=4.8–15.5, df=395, p<0.001).

bSignificantly different from somatizing women in scores on the Global Severity Index and on all scales except the anxiety scale (t=3.8–20.0, df=567, p<0.001).

FIGURE 2. Frequency of Health-Care-Seeking Behavior and Intention in the Past 6 Months Among Somatizing and Nonsomatizing Subjects Recently Immigrated to Israel From the Former Soviet Uniona

aComparisons of somatizing and nonsomatizing subjects used chi-square tests with Yates’s correction for continuity, df=1.

bSignificant group differences for health-care-seeking behavior (χ2=16.2, p<0.001; odds ratio=1.92) and intention (χ2=9.8, p<0.005; odds ratio=1.71).

cSignificant group differences for health-care-seeking behavior (χ2=17.8, p<0.001; odds ratio=3.61) and intention (χ2=60.4, p<0.0001; odds ratio=4.00).

dSignificant group differences for health-care-seeking behavior (χ2=6.1, p<0.05; odds ratio=2.20) and intention (χ2=16.5, p<0.001; odds ratio=2.15).

eSignificant group differences for health-care-seeking behavior (χ2=23.9, p<0.001; odds ratio=4.61) and intention (χ2=60.2, p<0.0001; odds ratio=4.93).

1. Flaherty JA, Kohn R, Levav I, Birz S: Demoralization in Soviet-Jewish immigrants to the United States and Israel. Compr Psychiatry 1988; 39:588–597Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Kohn R, Flaherty JA, Levav I: Somatic symptoms among older Soviet immigrants: an exploratory study. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1989; 35:350–360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ritsner M, Ponizovsky A: Psychological distress through immigration: the two-phase temporal pattern? Int J Soc Psychiatry 1999; 45:125–139Google Scholar

4. Ritsner M, Ponizovsky A, Ginath Y: Changing patterns of distress during the adjustment of recent immigrants: a one-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 95:494–499Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Zilber N, Lerner Y: Psychological distress among recent immigrants from the former Soviet Union to Israel, 1: correlates of level of distress. Psychol Med 1996; 26:493–503Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ritsner M, Ponizovsky A: Psychological symptoms among an immigrant population: a prevalence study. Compr Psychiatry 1998; 39:21–27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lipowski ZJ: Somatization: the concept and its clinical application. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:1358–1368Google Scholar

8. Escobar JI, Burnam MA, Karno M, Forsythe A, Golding JM: Somatization in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:713–718Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Baruffol E, Thilmany MC: Anxiety, depression, somatization and alcohol abuse: prevalence rates in a general Belgian community sample. Acta Psychiatr Belg 1993; 93:136–153Medline, Google Scholar

10. Swartz M, Landerman R, George LK: Somatization disorder, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991, pp 220–257Google Scholar

11. Escobar JL, Ribio-Stipec M, Canino G, Karno M: Somatic Symptom Index (SSI): a new and abridged somatization construct. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:140–146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Katon W, Lin E, Von Korff M, Rusco J, Lipscomb P, Bush T: Somatization: a spectrum of severity. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:34–40Link, Google Scholar

13. Gureje O, Simon GE, Ustun TB, Goldberg DP: Somatization in cross-cultural perspective: a World Health Organization study in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:989–995Link, Google Scholar

14. Simon GE, Von Korff M: Somatization and psychiatric disorder in the NIMH Epidemiological Catchment Area study. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1494–1500Google Scholar

15. Ford CV: The somatizing disorders. Psychosomatics 1986; 27:327–337Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wool CA, Barsky AJ: Do women somatize more than men? gender differences in somatization. Psychosomatics 1994; 35:445–452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ohaeri JU, Odejide OA: Somatization symptoms among patients using primary health care facilities in a rural community in Nigeria. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:728–731Link, Google Scholar

18. Piccinelli M, Simon G: Gender and cross-cultural differences in somatic symptoms associated with emotional distress: an international study in primary care. Psychol Med 1997; 27:433–444Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Portegiijs PJ, van der Horst FG, Proot IM, Krann HF, Gunther NC, Knottnerus JA: Somatization in frequent attenders of general practice. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1996; 31:29–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Robinson JO, Granfield AJ: The frequent consulter in primary medical care. J Psychosom Res 1986; 30:589–600Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Pang KY, Lee MH: Prevalence of depression and somatic symptoms among Korean elderly immigrants. Yonsei Med J 1994; 35:155–161Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Handelman L, Yeo G: Using explanatory models to understand chronic symptoms of Cambodian refugees. Fam Med 1996; 28:271–276Medline, Google Scholar

23. Buchwald D, Manson SM, von Knorring Al, Cloninger CR: Symptom patterns and causes of somatization in men, I: differentiation of two discrete disorders. Genet Epidemiol 1986; 3:153–169Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Castillo R, Waitskin H, Ramirez Y, Escobar JI: Somatization in primary care, with a focus on immigrants and refugees. Arch Fam Med 1995; 4:637–646Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Ponizovsky A, Ginath Y, Factourovich A, Levin K, Maoz B, Ritsner M: The impact of professional adjustment on the psychological distress of immigrant physicians. Stress Med 1996; 12:247–251Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Ritsner M, Ponizovsky A, Modai I: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among immigrant adolescents from the Soviet Union to Israel. J Am Ac Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1433–1441Google Scholar

27. Derogatis LR, Spencer RM: The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual, I. Baltimore, John Hopkins University School of Medicine, 1982Google Scholar

28. Escobar JI, Golding JM, Hough RL, Karno M, Burnam MA, Wells KB: Somatization in the community: relationship to disability and use of services. Am J Public Health 1987; 77:837–840Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Ritsner M, Rabinowitz J, Slyusberg M: The Demographic Psychosocial Inventory (DPSI): a new instrument to measure risk factors for adjustment problems among immigrants. Refuge 1995; 14:8–15Google Scholar

30. Escobar JI, Gara M, Silver RC, Waitzkin H, Holman A, Compton W: Somatisation disorder in primary care. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173:262–266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Good BJ: The heart of what’s the matter: the semantics of illness in Iran. Cult Med Psychiatry 1977; 1:25–58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Mirdal GM: The condition of “tightness”: the somatic complaints of Turkish migrant women. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1985; 71:287–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Ben-Noun L: [Chronic diseases in immigrants from Russia (CIS) at a primary care clinic and their sociodemographic characteristics]. Harefuah 1994; 127:441–445, 504–505 (Hebrew)Medline, Google Scholar

34. Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff D: Common symptoms in ambulatory care: incidence, evaluation, therapy, and outcome. Am J Med 1989; 86:262–266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Katon WJ, Walker EA: Medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 20):15–21Google Scholar

36. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Lipscomb P, Russo J, Wagner E, Polk E: Distressed high utilizers of medical care: DSM-III-R diagnoses and treatment needs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1990; 12:355–362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Lobo A, Garcia-Campayo J, Campos R, Marcos G, Perez-Echeverria MJ (Working Group for the Study of the Psychiatric and Psychosomatic Morbidity in Zaragoza): Somatisation in primary care in Spain, I: estimates of prevalence and clinical characteristics. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:344–348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Fink P: Psychiatric illness in patients with persistent somatisation. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:93–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Goldberg DP, Bridges KW: Somatic presentations of psychiatric illness in primary care setting. J Psychosom Res 1988; 32:137–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Betrus PA, Elmore SK, Hamilton PA: Women and somatization: unrecognized depression. Health Care Women Int 1995; 16:287–297Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Van Wijk CM, Kolk AM: Sex differences in physical symptoms: the contribution of symptom perception theory. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45:231–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Liu G, Clark MR, Eaton WW: Structural factor analysis for medically unexplained somatic symptoms of somatization disorder in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Psychol Med 1997; 27:617–626Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Ford CV: Illness as a lifestyle: the role of somatization in medical practice. Spine 1992; 17(Oct suppl):S338–S343Google Scholar