Differentiation of Homicidal Child Molesters, Nonhomicidal Child Molesters, and Nonoffenders by Phallometry

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to examine the ability of phallometry to discriminate among homicidal child molesters, nonhomicidal child molesters, and a comparison group of nonoffenders. METHOD: Twenty-seven child molesters who had committed or had attempted a sexually motivated homicide, 189 nonhomicidal child molesters, and 47 nonoffenders were compared on demographic variables and psychometrically determined responses to aural descriptions of sexual vignettes. Two phallometric indexes were used: the pedophile index and the pedophile assault index. The pedophile index was computed by dividing the subject’s highest response to an aural description of sex with a “consenting” child by his highest response to description of sex with a consenting adult. The pedophile assault index was computed by dividing the subject’s highest response to an aural description of assault involving a child victim by his highest response to description of sex with a “consenting” child. RESULTS: Homicidal child molesters, nonhomicidal child molesters, and nonoffenders were not significantly different in age or IQ. Homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters had significantly higher pedophile index scores than nonoffenders. Significantly more homicidal child molesters (14 [52%] of 27) and nonhomicidal child molesters (82 [46%] of 180) than nonoffenders (13 [28%] of 47) had pedophile index scores equal to or greater than 1.0, but homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters did not differ from each other. Significantly more homicidal child molesters (17 [63%] of 27) than either nonhomicidal child molesters (71 [40%] of 178) or nonoffenders (17 [36%] of 47) had pedophile assault index scores equal to or greater than 1.0, and nonhomicidal child molesters and nonoffenders were not significantly different from each other. Within-group analyses revealed that of the three groups, only the nonhomicidal child molesters exhibited a significant difference between their pedophile index scores and their pedophile assault index scores; their pedophile index scores were higher. CONCLUSIONS: Consistent with past research, the authors found that the pedophile index is useful in differentiating homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters from nonoffenders and that the pedophile assault index is able to differentiate homicidal child molesters from nonhomicidal child molesters and nonoffenders.

The utility of phallometric measures in the assessment and treatment of sexual offenders has become a controversial issue. There is evidence both for and against the ability of phallometric measures to discriminate between nonoffender and offender populations, or among different sex offender populations (1–4). Nevertheless, the evidence for the usefulness of phallometrics with groups of men who have been convicted of extrafamilial child sexual abuse is more substantial. In fact, a meta-analysis conducted in 1998 (5) suggested that phallometric assessment is one of the most reliable predictors of recidivism for child molesters, supporting its utility with this group at least.

There are several ways to rate deviant sexual arousal with phallometry. Perhaps the most common method is to calculate indexes reflecting relative sexual arousal or sexual preference to auditory descriptions of different types of sexual activity with various types of partners/victims (3, 6–8). Two such indexes are the pedophile index and the pedophile assault index. The pedophile index is typically calculated by dividing the highest phallometrically determined response to descriptions of “consenting” sex with a child by the highest response to descriptions of consenting sex with an adult. The pedophile assault index is typically calculated by dividing the highest phallometrically determined response to descriptions of coercive sex, sadistic sex, or nonsexual assault of a child by the highest response to descriptions of “consenting” sex with a child. Pedophile index values greater than 1.0 are considered to reflect a preference for children as sexual partners/victims over adults, although scores of 0.9 are generally considered to be of clinical concern. Similarly, pedophile assault index values greater than 1.0 are considered to reflect a preference for coercive sex, sadistic sex, or nonsexual assault of a child over noncoercive sexual abuse of a child.

The pedophile index and the pedophile assault index also appear to be useful in distinguishing among different groups of nonhomicidal child molesters. One study (9) reported that over half of the pedophiles and almost all of the incest offenders examined had pedophile index scores greater than 1.0. That is, both groups showed a deviant preference for descriptions of “consenting” sex with children over consenting sex with adult females. The pedophile assault index appeared to be much better at discriminating between these two groups. Six of the eight more dangerous pedophiles had pedophile assault index scores greater than 1.0, whereas none of the less dangerous incest offenders had pedophile assault index scores greater than 1.0. However, the small sample size precluded statistical analyses. This study was replicated with a larger sample of violent and nonviolent nonhomicidal child molesters (10). The more violent child molesters exhibited higher pedophile assault index scores than the less violent child molesters (no pedophile index evidence was reported).

There has been a paucity of research regarding sexual arousal patterns of homicidal sexual offenders. It has been suggested that many homicidal sexual offenders focus on sexually sadistic acts to achieve arousal and that this may be their major distinguishing feature (11–14). In support of this contention, one study using phallometry (14) found that homicidal sexual offenders showed the greatest deviant responses to sadistic stimuli compared with nonsexual murderers and nonhomicidal sexual offenders. Consistent findings come from our clinic (15), where we compared incest offenders and a mixed group of homicidal sexual offenders (i.e., involving adult and child victims). The results revealed that there was no difference between the groups in terms of the pedophile index, but homicidal sexual offenders had higher pedophile assault index scores than incest offenders, reflecting a greater preference for descriptions of assaultive acts with children. In a follow-up study examining homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters (16) we found, once again, that homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters did not differ in pedophile index scores but that homicidal child molesters had higher pedophile assault index scores than nonhomicidal child molesters.

In summary, previous research has provided evidence that the pedophile index can discriminate between nonhomicidal child molesters and nonoffenders and that the pedophile assault index can discriminate between homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters. However, in most previous studies using the pedophile assault index, sample sizes have typically been small and comparison groups have not been included. The present study was conducted to gather more information on the role of deviant sexual arousal in the assessment of sex offenders. We compared homicidal child molesters, nonhomicidal child molesters, and a group of nonoffenders. Both a pedophile index and a pedophile assault index were calculated for each participant.

Method

Participants

Participants were 27 child molesters who had committed or attempted a sexually motivated homicide, 189 nonhomicidal child molesters, and 47 nonoffenders (comparison group). All participants were men at least 18 years old, and all were assessed at the Royal Ottawa Hospital Sexual Behaviours Clinic between 1982 and 1992. Homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters had committed nonincestual sexual offenses against a female and/or male child under 16 years of age, were 18 years of age or older at the time of their offense, and were assessed as part of their adjudication or sentencing process. The comparison group was recruited through an advertisement and paid a $50 honorarium. The men in the comparison group had no criminal record or serious psychiatric or medical history, and all reported that they had never committed a sexual offense.

Procedure

The assessment process at the Sexual Behaviours Clinic routinely included several components. During interviews by staff psychiatrists, participants’ written consent was obtained for completion of all questionnaires and phallometric testing. Demographic data collected included age, marital status, education, and employment status. Data on the number and sex of victims, history of suicidal behavior, family historical features, and history of physical violence were also collected.

Measurement of sexual arousal

Changes in penile circumference in response to audio/visual stimuli were measured by means of an indium-gallium strain gauge and monitored with a Farrell Instruments CAT200 (Behavioral Technology, Salt Lake City). These data were then processed in an IBM-compatible computer for storage and printout.

Stimuli presentation

The order of stimulus presentation, held constant for all subjects, was computer controlled with MPV-Forth Version 3.05 software provided by Farrell Instruments. Videotapes were presented first, followed by a set of slides. Finally, subjects were presented with one or more of three series of audiotapes, according to the nature of the subject’s sexual offense. Only the results of arousal to the audiotape stimuli are presented here. The audiotapes consisted of 120-second vignettes that described sexual activities varying in age, sex, degree of consent, coercion, and/or violence portrayed (17). Each subject was presented with a full set containing one vignette from each category and instructed to allow normal arousal to occur.

The female child series consisted of descriptions of sexual activity with a female partner/victim in eight categories. The male child series consisted of eight corresponding vignettes involving a male partner/victim but also included one scenario involving an adult female partner. For each of the female child and male child series, two equivalent scenarios for each category were included. Categories were 1) child initiates, 2) child mutual, 3) nonphysical coercion of child, 4) physical coercion of child, 5) sadistic sex with child, 6) nonsexual assault of child, 7) consenting sex with female adult, and 8) sex with female child relative (incest).

The audiotape series used to identify sexual attraction to rape included two scenarios of 2 minutes’ duration for each of three categories: 1) consenting sex with adult female, 2) rape of adult female, and 3) nonsexual assault of adult female.

Scoring

The pedophile index was computed by dividing the highest response to the child initiates or child mutual stimulus by the highest response to the adult consenting stimulus. The pedophile assault index was computed by dividing the highest response to an assault stimulus involving a child victim (nonphysical coercion of child, physical coercion of child, sadistic sex with child, or nonsexual assault of child) by the highest response to the child initiates or child mutual stimulus.

Results

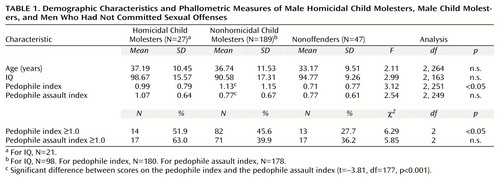

One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed on the demographic and phallometric variables; the results are presented in Table 1. Homicidal child molesters, nonhomicidal child molesters, and the comparison group did not significantly differ in age or IQ. A significant between-groups difference was found for pedophile index scores. Tukey least-significant-difference post hoc tests revealed that homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters had significantly higher pedophile indexes than the comparison subjects (p<0.05), but homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters did not differ from each other.

To further examine the ability of the pedophile index to discriminate among these three groups, a chi-square was performed on the percentage of men in each group with pedophile index scores of 1.0 or higher. As shown in Table 1, the overall chi-square was significant. Follow-up chi-squares revealed that significantly more homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters had pedophile index scores greater than or equal to 1.0 than did comparison subjects (χ2=4.96, df=1, p<0.05, and χ2=5.50, df=1, p<0.05, respectively) but that homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters did not differ from each other.

Between-groups differences in pedophile assault index scores were tested with a one-way ANOVA; the results are shown in Table 1. Although the omnibus F did not reach significance, post hoc analyses were conducted on the pedophile assault index scores because differences were expected between the homicidal child molesters and the other two groups, and this would not necessarily be reflected in the omnibus test because the number of homicidal child molesters was relatively small. Tukey least-significant-difference post hoc tests on the pedophile assault index revealed that homicidal child molesters had significantly higher scores than both the nonhomicidal child molesters and the comparison subjects (p<0.05), who did not differ from each other.

As with the pedophile index, a chi-square was performed on the percentage of men in each of the three groups with pedophile assault index scores equal to or greater than 1.0 (Table 1). Once again, despite a nonsignificant finding, a follow-up seemed justified because of the relatively small number of subjects in the homicidal child molester group. Follow-up chi-squares revealed that significantly more homicidal child molesters than both nonhomicidal child molesters and comparison subjects had pedophile assault index scores equal to or greater than 1.0 (χ2=4.33, df=1, p<0.05, and χ2=4.96, df=1, p<0.05, respectively) and that nonhomicidal child molesters and comparison subjects were not significantly different from each other.

Analyses of pedophile index and pedophile assault index scores in each of the three groups are presented in Table 1; t tests indicated that only the nonhomicidal child molesters exhibited a difference between their pedophile index and pedophile assault index scores. The pedophile index scores of the nonhomicidal child molesters were significantly higher than their pedophile assault index scores. No other significant differences were found.

Discussion

In general the results of the present investigation are consistent with the speculations concerning the role of deviant sexual arousal in homicidal sex offenders (11–15). They also support the contention that phallometric assessment is a useful tool in work with men who are sexually attracted to children (18–20).

In the present investigation homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters had significantly higher pedophile index scores than the nonoffenders. Homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters were also more likely than nonoffenders to have pedophile index scores of 1.0 or higher. There was evidence, although statistically less robust, that the homicidal child molesters were more likely than the other two groups to have pedophile assault index scores of 1.0 or higher. The comparison of pedophile index and pedophile assault index scores in each of the three groups is particularly instructive in this regard. The mean pedophile index score of the nonhomicidal child molesters was significantly higher than their mean pedophile assault index score.

Taken together, these findings suggest that, as a group, men who have committed nonviolent sexual offenses against children may derive little sexual pleasure from depictions of clearly assaultive acts against children. On the other hand, homicidal child molesters seem to be equally aroused by assaultive and nonassaultive depictions in which children are victims.

Although the overall results of the present investigation support the theory of previous reports, it is important to note that neither the pedophile index nor the pedophile assault index was as sensitive as one would like. Approximately half of the homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters did not exhibit more sexual arousal to child stimuli than to adult stimuli (i.e., approximately 50% had pedophile index scores less than 1.0). Furthermore, 10 (37%) of 27 of the homicidal child molesters did not demonstrate more sexual arousal to stimuli depicting coercive than noncoercive child sexual abuse (i.e., they had pedophile assault index scores less than 1.0). The relatively large number of subjects included in this study argues for the veracity of these findings.

It is possible that the assignment of subjects on the basis of offense history (e.g., nonhomicidal child molester or homicidal child molester) results in groups of offenders that are far from homogeneous. Clinical experience has demonstrated that many nonhomicidal child molesters, especially those with only a one-time offense history, may not be particularly sexually interested in children. Rather, their offense may have been opportunistic and involved drugs as a disinhibiter. It is also evident that in some cases men have murdered or attempted to murder children after sexually abusing them only when they became frightened about the possibility of being reported. Sometimes, even though no less devastating, this occurs in a thoughtless panic. Alternatively, a participant’s true sexual preferences may be masked by faking. Given the consequences of showing sexually deviant responses, this is easily understood (21, 22). Future research on the utility of phallometry should consider the inclusion of other categories, such as sadistic offenders designated by DSM-IV diagnoses, in the evaluation process. Another reasonable distinction is that related to repeat or predatory offenders as opposed to opportunistic offenders.

|

Received Oct. 8, 1999; revisions received April 18 and May 23, 2000; accepted July 15, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry and the Department of Psychology, University of Ottawa. Address reprint requests to Dr. Firestone, School of Psychology and Department of Psychiatry, 120 University Private, Ottawa, Ont., Canada K1N 6N5; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Harris GT, Rice ME, Quinsey VL: Psychopathy as a taxon: evidence that psychopaths are a discrete class. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:387–397Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Barbaree HE, Baxter DJ, Marshall WL: Brief research report: the reliability of the rape index in a sample of rapists and nonrapists. Violence Vict 1989; 4:299–306Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Baxter DJ, Marshall WL, Barbaree HE, Davidson PR, Malcolm PB: Deviant sexual behavior: differentiating sex offenders by criminal and personal history, psychometric measures, and sexual response. Criminal Justice and Behavior 1984; 11:477–501Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Rice ME, Harris GT, Quinsey VL: A follow-up of rapists assessed in a maximum-security psychiatric facility. J Interpersonal Violence 1990; 5:435–448Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Hanson RK, Bussière MT: Predicting relapse: a meta-analysis of sexual offender recidivism studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:348–362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Barbaree HE, Marshall WL: Erectile responses among heterosexual child molesters, father-daughter incest offenders, and matched nonoffenders: five distinct age preference profiles. Can J Behavioural Sci 1989; 21:70–82Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Lalumière ML, Quinsey VL: The discriminability of rapists from nonoffenders using phallometric measures: a meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior 1994; 21:150–175Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Marshall WL, Fernandez YM: Phallometric testing with sexual offenders: limits to its value. Clin Psychol Rev (in press)Google Scholar

9. Abel GG, Becker JV, Murphy WD, Flanagan B: Identifying dangerous child molesters, in Violent Behavior: Social Learning Approaches to Prediction, Management and Treatment. Edited by Stuart RB. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1981, pp 116–137Google Scholar

10. Avery-Clark C, Laws DR: Differential erection response patterns of sexual child abusers to stimuli describing activities with children. Behavior Therapy 1984; 15:71–83Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Brittain RP: The sadistic murderer. Med Sci Law 1970; 10:198–207Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Burgess AW, Hartman CR, Ressler RK, Douglas JE, McCormack A: Sexual homicide: a motivational model. J Interpersonal Violence 1986; 1:251–272Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Dietz PE: Mass, serial and sensational homicides. Bull NY Acad Med 1986; 62:477–491Medline, Google Scholar

14. Langevin R, Ben-Aaron MH, Wright P, Marchese V, Handy L: The sex killer. Ann Sex Res 1988; 1:123–301Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Firestone P, Bradford JM, Greenberg DM, Larose MR: Homicidal sex offenders: psychological, phallometric, and diagnostic features. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1998; 26:537–552Medline, Google Scholar

16. Firestone P, Bradford JM, Greenberg DM, Larose MR, Curry S: Homicidal and nonhomicidal child molesters: psychological, phallometric, and criminal features. Sex Abuse 1998; 10:305–323Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Abel GG, Blanchard EB, Barlow DH: Measurement of sexual arousal in several paraphilias: the effects of stimulus modality, instructional set and stimulus content on the objective. Behav Res Ther 1981; 19:25–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Chaplin TC, Rice ME, Harris GT: Salient victim suffering and the sexual responses of child molesters. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995; 63:249–255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Quinsey VL: Men who have sex with children, in Law and Mental Health: International Perspectives, vol 2. Edited by Weisstub DN. New York, Pergamon Press, 1986, pp 140–172Google Scholar

20. Quinsey VL, Laws DR: Validity of physiological measures of pedophilic sexual arousal in a sexual offender population: a critique of Hall, Proctor, and Nelson. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990; 8:886–888Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Hall GCN, Proctor WC, Nelson GM: Validity of physiological measures of pedophilic sexual arousal in a sexual offender population. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:118–122Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Laws DR, Holmen ML: Sexual response faking by pedophiles. Criminal Justice and Behavior 1978; 5:343–356Crossref, Google Scholar