Relationship Between Antidepressants and Suicide Attempts: An Analysis of the Veterans Health Administration Data Sets

Abstract

Objective: In late 2006, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration advisory committee recommended that the 2004 black box warning regarding suicidality in pediatric patients receiving antidepressants be extended to include young adults. This study examined the relationship between antidepressant treatment and suicide attempts in adult patients in the Veterans Administration health care system. Method: The authors analyzed data on 226,866 veterans who received a diagnosis of depression in 2003 or 2004, had at least 6 months of follow-up, and had no history of depression from 2000 to 2002. Suicide attempt rates overall as well as before and after initiation of antidepressant therapy were compared for patients who received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), new-generation non-serotonergic-specific (non-SSRI) antidepressants (bupropion, mirtazapine, nefazodone, and venlafaxine), tricyclic antidepressants, or no antidepressant. Age group analyses were also performed. Results: Suicide attempt rates were lower among patients who were treated with antidepressants than among those who were not, with a statistically significant odds ratio for SSRIs and tricyclics. For SSRIs versus no antidepressant, this effect was significant in all adult age groups. Suicide attempt rates were also higher prior to treatment than after the start of treatment, with a significant relative risk for SSRIs and for non-SSRIs. For SSRIs, this effect was seen in all adult age groups and was significant in all but the 18–25 group. Conclusions: These findings suggest that SSRI treatment has a protective effect in all adult age groups. They do not support the hypothesis that SSRI treatment places patients at greater risk of suicide.

In October 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ordered pharmaceutical companies to add a black box warning regarding the possible link between antidepressant treatment and suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents. This action, which imposed the FDA’s most serious drug label warning, was based on the agency’s meta-analysis of 25 randomized controlled clinical trials (1 , 2) , although no suicides were reported in any of these trials. In contrast to the FDA’s findings, Gibbons et al. (3) showed that at the county level, U.S. prescription rates for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are inversely related to completed suicide rates in children and young adolescents after adjustment for access to mental health care and demographic factors.

In December 2006, the FDA’s Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee recommended that the black box warning be extended to include young adults, and in May 2007, the FDA asked drug manufacturers to revise their labels accordingly. The committee’s recommendation was based on results of a meta-analysis of data on nearly 100,000 patients from 372 randomized controlled trials of SSRIs and new-generation non-serotonergic-specific antidepressants (non-SSRIs). Overall, the analysis indicated a protective effect of antidepressants on suicidal ideation and behavior (odds ratio=0.83). When the data were stratified by age, antidepressant treatment was associated with a significantly lower risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in patients age 65 and older (odds ratio=0.37) and in patients in the range of ages 25–64 (odds ratio=0.79) but a higher risk in adult patients under age 25 (odds ratio=1.62), although the latter association fell short of statistical significance. Even in this large sample, there were only eight suicides altogether—two of 27,164 placebo subjects, five of 39,729 subjects on test drug, and one of 10,489 subjects on active control. Gibbons et al. showed in their national county-level study (4) that prescription rates for both SSRI and non-SSRI antidepressants are inversely related to suicide rates in adults, whereas prescription rates for tricyclic antidepressants are positively related to suicide rates in adults.

In light of the favorable inverse relationship between SSRI prescription rates and suicide rates seen in adults (4) , older adolescents and young adults (5) , and younger adolescents and children (3) , the FDA findings seem contradictory. Given that the 2004 black box warning appears to have resulted in a drop in the rate at which antidepressant prescriptions are written for children, adolescents, and young adults and very likely explains the 2004 increase in the suicide rates for those age groups, the recent extension of the black box warning to young adults carries the risk of further increasing suicide rates (6) .

In this study, we used an extensive Veterans Administration (VA) database to examine the association between various types of antidepressants and suicide attempts to assess whether the use of these antidepressants may increase the risk of suicide attempt in adult patients with depression.

Method

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical data sets contain national administrative data for VHA-provided health care utilized primarily by veterans but also by some nonveterans (e.g., VHA employees and research participants). These data are extracted from the National Patient Care Database, maintained by the VHA Office of Information at the Austin Automation Center, the central repository for VA data. National Patient Care Database records include up-to-date patient demographic information, the date and time of service, the name of the practitioner(s) who provided the service, the location where the service was provided, any diagnoses made, and any procedures performed. The Pharmacy Benefits Management Database is a national database of information on all prescriptions dispensed within the VHA system beginning with fiscal year 1999. Inpatient intravenous and unit dose prescription orders dispensed in a VA facility and outpatient prescription orders filled at a VA Pharmacy or Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy are extracted monthly from each Veterans Health Information Systems Technology and Architecture site and loaded into the Pharmacy Benefits Management Database.

The study sample was based on a cohort of 226,866 veterans (mean age=57.4 years (SD=14.8); 2.6% Hispanic, 0.2% American Indian, 6.7% Black, 0.2% Asian, 26.0% White, 64.3% unknown; 8.4% female) who experienced depressive disorders or unipolar mood disorders (ICD-9-CM codes 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, and 311) in 2003 or 2004, had at least 6 months of follow-up, and had no history of these disorders or antidepressant treatment from 2000 to 2002. These diagnostic codes and entrance criteria were selected to define a reasonably homogeneous population of patients who were experiencing a new depressive episode. Complete longitudinal records for all inpatient and outpatient visits and complete pharmacy records were available for all patients. The VHA database does not provide cause-of-death information, so the focus of our analysis was on suicide attempts that were sufficiently serious to have led to contact with the VA health care system. Patients were considered to have made suicide attempts if they had suicide-related diagnostic codes (E950–E959) in records for inpatient stays or outpatient visits. These codes include suicide or self-inflicted injury from poisoning, hanging, submersion, firearms, cutting or piercing, jumping from high places, or other means. It is possible that in some cases these suicide attempts led to fatalities after hospitalization. In any case, our analysis ignored lethal attempts that did not lead to contact with the VA health care system.

Comparisons of suicide rates within subjects before and after SSRI treatment were conducted using McNemar’s test, and corresponding relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed. Comparisons of suicide rates between subjects (e.g., those treated with an SSRI versus those not treated with an SSRI) were analyzed using chi-square tests, and corresponding odds ratios and 95% CIs were computed. The effect of the SSRIs in combination with non-SSRI and/or tricyclic antidepressant treatments relative to the same antidepressant treatment without the SSRI was also analyzed using chi-square tests and corresponding odds ratios and 95% CIs.

Results

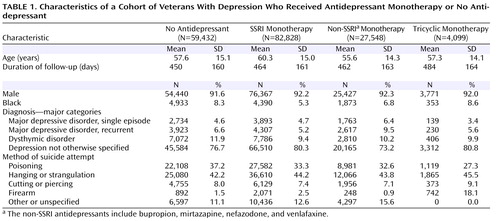

Of the total cohort of 226,866 patients with depression, 59,432 were not treated with an antidepressant, 114,475 were treated with one or more medications of a single antidepressant type (72% with SSRIs, 24% with non-SSRI antidepressants [bupropion, mirtazapine, nefazodone, and venlafaxine], and 4% with tricyclic antidepressants), and 52,959 were treated with a combination of different types of antidepressants. Table 1 presents the sample characteristics for patients who did not receive antidepressant treatment and those who received antidepressant monotherapy with an SSRI, a non-SSRI, or a tricyclic. Overall, the groups were similar in age and sex composition. The average duration of follow-up was similar across the treatment categories, although patients who did not receive an antidepressant were observed 2 weeks less on average than those who received antidepressant monotherapy. Slightly more patients who had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (single episode or recurrent) were treated with non-SSRI antidepressants than with SSRIs or tricyclics.

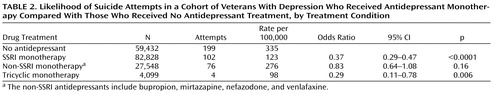

The overall rate of suicide attempt after initiation of treatment with an SSRI, either alone or in combination with another antidepressant, was 364/100,000. By comparison, the rate for all other patients with depression—those who were treated with a non-SSRI and/or a tricyclic as well as those who did not receive an antidepressant—was 1,057/100,000. The overall odds ratio for the comparison of SSRI treatment and all other treatment categories (including no antidepressant treatment) was 0.34 (95% CI=0.31–0.38, p<0.0001). As Table 2 shows, comparison of those who were not treated with an antidepressant and those who were treated with an SSRI alone revealed a statistically significant effect of SSRI treatment on rates of suicide attempt. A similar effect was observed for tricyclics, and a weaker, nonsignificant effect was observed for non-SSRIs. When an SSRI was taken in combination with a tricyclic or a non-SSRI, there were no statistically significant differences in the rate of suicide attempt as compared with the same treatment regimen without the SSRI.

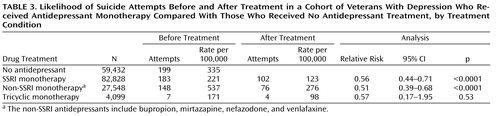

As shown in Table 3 , among patients who received monotherapy with an SSRI or a non-SSRI antidepressant, the rate of suicide attempt was significantly lower after treatment than before treatment. For those treated with tricyclic antidepressants, the rate was lower after treatment, but the difference was not significant, possibly because of the smaller number of patients treated with a tricyclic alone and the small number of events. Among patients receiving SSRIs in combination with one or more non-SSRIs or tricyclics or both, the suicide attempt rate before treatment (402/100,000) was higher than the rate after treatment (363/100,000), although the difference was not significant.

These results represent a lower bound on the actual difference in attempt rates before and after treatment, since the duration of observation was greater on average after antidepressant treatment was initiated than before. For patients treated with SSRIs, the average observation period before antidepressant treatment was 297 days, compared with 433 days following the start of treatment. Similar differences were seen for patients treated with non-SSRIs (319 days versus 412 days) and tricyclics (342 days versus 388 days). Adjusted for number of patient-months at risk, the relative risks of suicide attempt following the start of treatment versus prior to initiation of treatment were 0.383 for SSRIs (95% CI=0.301–0.488, p<0.0001), 0.397 for non-SSRIs (95% CI=0.302–0.523, p<0.0001), and 0.505 for tricyclics (n.s.). These person-month analyses, however, should be tempered by the possibility that risk of suicide attempt varies with how much time has passed since the start of antidepressant treatment. There are clinical indications that the risk of serious suicide attempt may be higher early on in the course of antidepressant treatment and then decrease after the first month of treatment (7) .

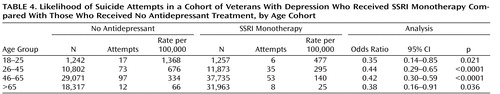

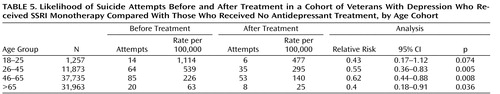

Finally, we repeated the analyses for different age groups and obtained similar results. Comparison of suicide attempt rates for depressed patients who received an SSRI alone and those who did not receive antidepressant treatment ( Table 4 ) showed a significantly lower risk with SSRIs in all age groups. Comparison of suicide attempt rates before and after treatment with SSRI monotherapy ( Table 5 ) also revealed lower risk for patients in all age groups; the relationship was significant in all but the 18–25 age group, possibly because of the smaller number of patients in that age group in the VA population and the small number of events.

Discussion

Our findings from our analysis of VA data are consistent with the hypothesis that treatment with SSRIs lowers the risk of suicide attempt in adults with depression and do not support the hypothesis that SSRIs increase the risk of suicidal behavior in adults. In this cohort of 226,866 adults experiencing a new episode of depression, the risk of suicide attempt among patients treated with an SSRI was about one-third that of patients who were not treated with an SSRI. On the basis of indication alone, we would not have expected a lower risk in those taking SSRIs (including those receiving SSRIs in combination with other antidepressants), since patients treated with SSRIs would generally be those who were more severely depressed and therefore would have a higher risk of suicide attempt. We also found evidence that the risk of suicide attempt was significantly higher before SSRI treatment than after the start of treatment, a finding that is consistent with the results of Simon et al. (7) . When we stratified the sample by whether or not patients received SSRIs in combination with other types of antidepressant as a way to control for severity of illness or for treatment resistance, we found no evidence of a greater risk of suicide attempt when an SSRI was given in combination with another type of antidepressant. For patients who were treated with an SSRI alone, the risk of suicide attempt was only 37% of that for patients receiving no antidepressant. The convergence of both within-subject results (before and after initiation of SSRI treatment) and between-subjects results (those treated with an SSRI compared with those not treated with an SSRI) clearly illustrates the lower risk of suicide attempt associated with SSRIs. Similar effects were observed for monotherapy with the new-generation non-SSRIs.

These results are consistent with those of our earlier ecological studies with adults (4) and with younger adolescents and children (3) , in which we found significant inverse associations of SSRI prescription rates and completed suicide rates at the county level in the United States, adjusted for case-mix variation. Valuck et al. (8 , 9) , using both child and adult person-level data from a large-scale insurance claims database, found no association between use of SSRIs and likelihood of suicide attempt. Meta-analyses of data compiled by the FDA from new drug applications for antidepressants and of data on paroxetine use in adults (10 – 12) also found no evidence of higher rates of suicide or suicide attempt. A meta-analysis of studies examined by the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (13) involving more than 40,000 individuals in 477 randomized placebo-controlled trials of SSRIs, mostly for the indication of depression, found 16 suicides, 172 episodes of nonfatal self-harm, and 177 episodes of suicidal ideation. Use of SSRIs was not associated with a greater risk of suicide, and with an odds ratio of 0.85 compared with placebo, a protective effect could not be ruled out. The results for effects of SSRIs versus placebo on suicidal ideation and nonfatal self-harm were not statistically significant. Fergusson et al. (14) examined 702 randomized controlled trials in which SSRIs were compared with placebo or an active comparator, for any clinical condition. However, fewer than half of these studies (345 trials) provided systematic data on suicides and suicide attempts, and those without systematic data were excluded from the meta-analysis. In this subset of studies, they found more suicide attempts in the SSRI group compared with the placebo group but no differences compared with the new-generation non-SSRI antidepressant groups; they also found no difference in suicide rates. In a matched case-control study of 159,810 patients in the U.K. using antidepressants from 1993 to 1999, the risk of first-time suicidal ideation or behavior did not differ between those receiving SSRIs and those receiving tricyclic antidepressants (15) . A nested case-control study of 146,095 individuals receiving a first antidepressant prescription for treatment of depression found a greater risk of nonfatal self-harm among youths receiving SSRIs compared with those receiving tricyclics (odds ratio=1.9) but no drug difference in adults (16) . The authors noted that while these data raise the possibility that youths are more vulnerable to effects of SSRIs than adults, it is also possible that SSRIs are used more commonly in patients considered to be at greater risk of suicidal behavior. Simon et al. (7) , in a U.S. study of 65,103 patients with 82,285 episodes of depression from 1999 to 2003, improved on the design of the preceding studies by also examining the 1-month period before the start of antidepressant treatment. They found that the risk of suicide attempt was highest during the month before medication was initiated and declined progressively thereafter. They found no greater risk of suicide attempt among patients receiving SSRIs and/or non-SSRIs in the months after starting treatment compared with the month before treatment, and in fact the risk of suicide attempt decreased with time in treatment.

As noted earlier, the FDA recently reported a meta-analysis of 372 placebo-controlled studies (17) that showed an overall protective effect of antidepressants on suicidal ideation and behavior (odds ratio=0.83). When the data were stratified by age for all psychiatric diagnoses, FDA researchers found suicide attempt rates of 250/100,000 in patients age 65 and older who received placebo and 31/100,000 in those who received test drug (SSRIs or new-generation non-SSRIs) and 147/100,000 in placebo patients and 129/100,000 in test drug patients 31–64 years of age. They found a statistically nonsignificant higher rate of suicide attempt in patients 18–24 years of age treated with test drug compared with those who received placebo (551/100,000 versus 269/100,000).

We found a similar suicide attempt rate for VA patients 18–25 years of age who were treated with an SSRI (477/100,000 in our VA data versus 551/100,000 in the FDA data). However, the rate of suicide attempt we found in untreated depressed patients 18–25 years of age was five times higher than the rate the FDA found in placebo patients enrolled in randomized controlled trials (1,368/100,000 in the VA data versus 269/100,000 in the FDA data). This difference points to the much lower risk of suicide attempt in depressed patients enrolled in randomized controlled trials compared with those in the general population, and it is a plausible explanation for the difference between the FDA findings and ours, both here and in our previous ecological studies (3 , 4) .

Our study had several limitations that should be mentioned. First, despite our attempt to eliminate bias due to the nonrandom assignment of patients to medications, confounding by selection remains a possibility. Nevertheless, much of the bias would very likely be in the opposite direction. For example, as previously noted, we would expect patients receiving SSRIs, either alone or in addition to other antidepressants, to have more severe or more treatment-resistant illness than those receiving no antidepressant. Thus, we would expect the suicide attempt rate among patients receiving SSRIs, either alone or in combination with other antidepressants, to be higher than the rate among patients not treated with an antidepressant, rather than lower, as we observed. Second, our results apply to suicide attempts only; our data did not include lethal and other attempts that did not result in contact with the VA medical record system. Whether our results also hold for completed suicide remains an open question. We are attempting to obtain cause-of-death information for this cohort and hope to be able to address this question. Third, this is largely a male population, and our results may not directly apply to women.

In summary, we found that for a largely male adult population, treatment with SSRIs and new-generation non-SSRI antidepressants (bupropion, mirtazapine, nefazodone, and venlafaxine) was not associated with a greater risk of suicide attempt than treatment with tricyclics or no antidepressant treatment. By contrast, our analyses support the hypothesis that treatment with SSRIs significantly decreases the risk of suicide attempt. Our data are consistent with the FDA’s finding of a statistically significant effect of SSRI and non-SSRI antidepressant treatment on suicide attempt rates in adults age 65 and older and on rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in adults older than 25. However, in contrast to the FDA’s findings, our analysis of the VA data indicates that these protective effects also apply to patients in the 18- to 25-year-old age group. Our results provide strong support for the hypothesis that antidepressants decrease the risk of suicide attempt in depressed patients throughout adulthood. The data thus suggest that the recent extension to young adults of the black box warning on risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in pediatric patients treated with antidepressants may further decrease antidepressant treatment of depression in the United States and increase suicidality in individuals with depression.

1. Hammad TA: Review and evaluation of clinical data. Washington, DC, Food and Drug Administration, Aug 16, 2004 (http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/04/briefing/2004-4065b1-10-TAB08-Hammads-Review.pdf)Google Scholar

2. Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J: Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:332–339Google Scholar

3. Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ: The relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicide. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1898–1904Google Scholar

4. Gibbons R, Hur K, Bhaumik D, Mann J: The relationship between antidepressant medication use and rate of suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:165–172Google Scholar

5. Olfson M, Shaffer D: Marcus SC, Greenberg T: Relationship between antidepressant medication treatment and suicide in adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:978–982Google Scholar

6. Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Marcus S, Mann JJ, Erkens J, Herings R: Early evidence on the effects of the FDA black box warning on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

7. Simon GE, Savarino J, Operskalski B, Wang PS: Suicide risk during antidepressant treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:41–47Google Scholar

8. Valuck RJ, Libby AM, Sills MR, Giese AA, Allen RR: Antidepressant treatment and risk of suicide attempt by adolescents with major depressive disorder: a propensity-adjusted retrospective cohort study. CNS Drugs 2004; 18:1119–1132Google Scholar

9. Valuck RJ, Libby AM, Morrato EH, Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Oquendo MA: Antidepressant treatment and risk of suicide attempt by adults with major depressive disorder. Poster (abstract 87) presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Dec 11–15, 2005, Waikoloa, HawaiiGoogle Scholar

10. Khan A, Khan S, Kolts R, Brown WA: Suicide rates in clinical trials of SSRIs, other antidepressants, and placebo: analysis of FDA reports. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:790–792Google Scholar

11. Montgomery SA, Dunner DL, Dunbar GC: Reduction of suicidal thoughts with paroxetine in comparison with reference antidepressants and placebo. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1995; 5:5–13Google Scholar

12. Zaninelli R, Meister W: The treatment of depression with paroxetine in psychiatric practice in Germany: the possibilities and current limitations of drug monitoring. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997; 30:9–20Google Scholar

13. Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA’s safety review. BMJ 2005; 330:385–389Google Scholar

14. Fergusson D, Doucette S, Glass KC, Shapiro S, Healy D, Hebert P: Association between suicide attempts and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMJ 2005; 330:396–402Google Scholar

15. Jick H, Kaye JA, Jick SS: Antidepressants and the risk of suicidal behaviors. JAMA 2004; 292:338–343Google Scholar

16. Martinez C, Rietbrock S, Wise L, Ashby D, Chick J, Moseley J, Evans S, Gunnell D: Antidepressant treatment and the risk of fatal and non-fatal self harm in first episode depression: nested case-control study. BMJ 2005; 330:389–395Google Scholar

17. US Food and Drug Administration: Clinical review: relationship between antidepressant drugs and suicidality in adults. (http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/2006-4272b1-01-FDA.pdf)Google Scholar