F.J. Gall and the Phrenological Movement

The doctrine of phrenology was at least as influential in the first half of the 19th century as psychoanalysis was in the first half of the 20th (1) . The movement started with Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828), a German-born physician, anatomist, and physiologist who lived in Paris.

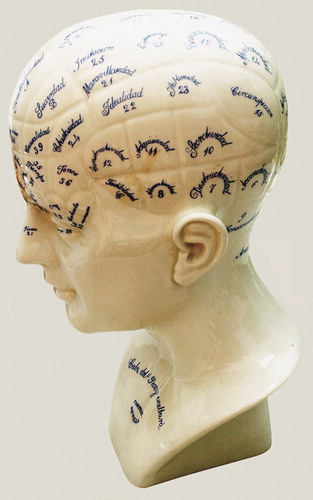

Figure 1. Photograph shows a handsome life-sized 19th-century ceramic phrenology bust (15 inches high). The maker mark, “PICKMAN Y CA./CHINA OPACA/SEVILLA,” indicates a Spanish ceramics company established in 1841 by Charles Pickman, originally from Liverpool. Photo courtesy of the authors.

Phrenology had a major influence on science and society, and it pervaded various areas of culture (1). The doctrine’s rapid dissemination, its popularization, and its use in specialized phrenologists’ offices quickly caused it to be regarded as a typical example of pseudoscience and its practice as a form of charlatanism (2) .

However, Gall’s work proved important for the biological study of the mind in three ways. First, it was the origin of modern brain localization (3) . Second, it established psychology as a biological science (4) . Many contemporary psychiatrists used the doctrine even though they did not completely accept it, much in the way that many people today accept Freudian ideas and terminology without totally embracing psychoanalysis (5) . And third, on a more general level, Gall’s work favored the emergence of a naturalistic approach to the study of man and played an important part in the development of evolutionist theories, anthropology, and sociology (4) .

It would not be much of an exaggeration to say that today no one remembers Gall the sage and neuroanatomist, but everyone knows him as a master of ceremonies and a phrenologist.

1. Ackerknecht EH: Medicine at the Paris Hospitals, 1794–1848. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1967Google Scholar

2. Young RM: The functions of the brain: Gall to Ferrier. Isis 1968; 59:261–268Google Scholar

3. McHenry LC: Garrison’s History of Neurology. Springfield, Ill, Charles C Thomas, 1969Google Scholar

4. Young RM: Franz-Joseph Gall, in Dictionary of Scientific Biographies. Edited by Gilliespie CC. New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972Google Scholar

5. Hunter R, Macalpine I: Three Hundred Years of Psychiatry (1535–1860), 2nd ed. London, Oxford University Press, 1970Google Scholar