Familial Aggregation of Illness Chronicity in Recurrent, Early-Onset Major Depression Pedigrees

Abstract

Objective: The authors used a large sample collected for genetic studies to determine whether a chronic course of illness defines a familial clinical subtype in major depressive disorder. Method: A measure of lifetime chronicity of depressive symptoms (substantial mood symptoms most or all of the time) was tested for familial aggregation in 638 pedigrees from the Genetics of Recurrent Early-Onset Depression (GenRED) project. Results: In subjects with chronic depression, the mean age at illness onset was lower and rates of attempted suicide, panic disorder, and substance abuse were higher than among those with nonchronic depression. Chronicity was assessed in 37.8% of affected first-degree relatives of probands with chronic depression and in 20.2% of relatives of probands with nonchronic depression. Analysis using the generalized estimating equation model yielded an odds ratio of 2.52 (SE=0.39, z=6.02, p<0.0001) for the likelihood of chronicity in a proband predicting chronicity in an affected relative. With stratification by proband age at illness onset, the odds ratio for chronicity in relatives by proband chronicity status was 6.17 (SE=2.09, z=5.35, p<0.0001) in families of probands whose illness onset was before age 13 and 1.92 (SE=0.34, z=3.72, p<0.0001) in families of probands whose illness started at age 13 or later. Conclusions: These findings suggest that chronicity of depressive symptoms is familial, especially in preadolescent-onset illness. Chronicity is also associated with other indicators of illness severity in recurrent, early-onset major depression. Further study using chronicity as a subtype in the genetic analysis of depressive illness is warranted. Refinement of the definition of chronicity in depressive illness may increase the power of such studies.

Although genetic epidemiology studies suggest that a substantial portion of the risk of serious depressive disorders is conferred by genetic factors (1) , no risk-conferring genes have been definitively identified. As with common diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and cancer, an individual’s susceptibility to mood disorders such as major depressive disorder appears to be a genetically complex trait, determined by multiple interacting genes as well as by environmental influences (2) . A useful strategy for resolving the genetic heterogeneity of complex traits has been to focus analytic efforts on narrowly defined phenotypes that share clinical features, as these may identify cases that are more genetically homogeneous. For example, the breast cancer gene BRCA1 was identified only when data from families with early-onset breast cancer and a high incidence of ovarian cancer were analyzed separately from families with late-onset breast cancer (3) . In bipolar disorder, several clinical features have been shown to be familial, including psychotic symptoms (4) , panic disorder (5) , and episode frequency (6) . Follow-up of some of these findings has provided enhanced evidence for linkage in family groups defined by clinical subtype (7) . In major depressive disorder, two illness features have been robustly associated with increased familial risk: recurrent episodes and an early age at onset (1 , 8–10) .

Symptom chronicity has been increasingly recognized as an important clinical feature of depressive illness. Although many patients with recurrent episodes of major depression experience remission with few residual symptoms between episodes, approximately 25% of patients with major depression have chronic residual depressive symptoms of varying severity with only incomplete remission over many years (11) . Classifying patients in terms of illness chronicity has been problematic, however, because of the variety of definitions of chronicity that can be used. Using DSM-IV criteria, it is possible to categorize chronic depressive illness in several ways. Patients with the more severe symptoms of major depression are diagnosed as having a chronic major depressive episode if symptoms have persisted for at least 2 years. Major depressive disorder may be characterized as “without full interepisode recovery” if the patient has had an incomplete recovery between the two most recent episodes. Dysthymic disorder, a separate diagnostic entity, is characterized by less severe depressive symptoms that have lasted at least 2 years.

The DSM-IV criteria do not address the lifetime course of illness, however. The course specifiers “chronic” and “without full interepisode recovery,” may, for example, be applied to an illness characterized by episodes of several years of depressive symptoms separated by long periods of complete remission, which lacks the features suggested by longitudinal studies to be characteristic of chronic depressive illness—frequent episodes, incomplete remission, and prominent residual symptoms throughout the course of illness.

There is some evidence suggesting that aspects of chronicity aggregate in families, which may help resolve genetic heterogeneity. Several studies have found elevated rates of dysthymia in relatives of probands with dysthymia (12 – 14) . Klein and colleagues (14) found a higher rate of chronic major depression (defined as major depressive disorder with at least one year-long major depressive episode) in relatives of probands with chronic major depression, but this finding did not reach statistical significance. They also reported that rates of major depression were significantly greater among relatives of young adult probands with chronic depressive disorders (dysthymic disorder and major depressive disorder with at least one year-long major depressive episode) than among relatives of probands with episodic major depressive disorder.

For this study, we sought to determine whether lifetime chronicity of illness aggregated in 638 families ascertained for a study of the genetics of recurrent, early-onset major depressive disorder. Diagnosticians assessed lifetime course of illness in subjects with major depressive disorder through direct interviews coupled with reviews of medical records and family informant data. Familial aggregation was determined through analysis of all first-degree relatives and of siblings only and by using both the family and the individual relative as the unit of analysis. In addition, because there is epidemiological evidence that preadolescent-onset major depressive disorder has a greater association with major depressive disorder in family members (15) , we stratified the probands into groups with either preadolescent or later onset. To our knowledge, no study has previously reported on familial aggregation of chronicity in depressive illness defined in this way.

Method

Ascertainment

The background and methods of the six-site Genetics of Recurrent Early-Onset Depression (GenRED) project have been described in detail elsewhere (8) . The GenRED project aimed to collect data on sibling pairs affected with recurrent, early-onset major depressive disorder and on other relatives, both first-degree and more distant. Families were recruited opportunistically through clinical settings, Internet announcements, and newspaper, magazine, and radio advertising. Prospective probands, who were not required to be in treatment, were screened briefly by telephone to determine whether the family was likely to be eligible. If eligibility was likely, arrangements were made to put relatives and recruiters in contact.

To be eligible, families had to have probands with recurrent, early-onset major depressive disorder, defined as either 1) at least two major depressive episodes according to DSM-IV criteria, with an illness onset before age 31 or 2) a single episode of major depression that lasted 3 years and began before age 31. Probands were excluded if they had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar I or II disorder. For family eligibility, probands also had to have at least one sibling who also had recurrent, early-onset major depressive disorder. For these siblings, “recurrent” was defined as it was for the probands but with an illness onset by age 40. This difference was incorporated because of epidemiological evidence indicating that relatives of probands in their 20s have a higher risk of the onset of major depression in their 30s than in their 20s (16) . Exclusionary criteria were the same as for probands except that affected siblings with bipolar II were not excluded. In addition to assessment of the eligible sibling pairs, available first-degree relatives and parents were included whenever possible.

For the analysis reported here, any first-degree relative with a history of at least one major depressive episode with any onset age was included.

Assessment

Study procedures were explained in detail to study subjects, and subjects provided written informed consent. Subjects were interviewed in person or by telephone by trained research clinicians (master’s level or higher) using the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies, version 3.0 (17) , a semistructured interview that assesses the severity and time course of depressive, manic, and hypomanic symptoms over the subject’s lifetime along with several other categories of psychopathology. The interview documents the onset and duration of mood episodes and the presence or absence of depressive symptoms; it also provides an unstructured but detailed assessment of the subject’s lifetime course of illness, documenting periods of prodromal and residual symptoms as well as active, syndromal levels of illness. Interviewing clinicians prepared narrative reports of the results of the interview and made the global assessment of the subjects’ lifetime course of mood disorder by classifying subjects as having a “remitting” course (“good remissions substantially longer than episodes”), a “double or chronic” course (“substantial mood symptoms most or all of the time”), or a course with “frequent/brief episodes (<3 weeks) without prolonged remissions.” Residual categories were “never had major depressive disorder” and “other.” Best-estimate ratings of lifetime severity were made on a scale from 1 to 4 in which 4 was the most severe, indicating that the subject had experienced psychotic symptoms, been hospitalized, received ECT, made a suicide attempt, or experienced “complete incapacitation (unable to provide for essential self-care).”

All available clinical data, including screening data, the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies, family history data, and available medical records, were reviewed by two noninterviewing research clinicians who were blind to each other’s diagnostic findings. Each made a final best-estimate diagnosis using DSM-IV criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by review by a third clinician. The two clinicians also reviewed the lifetime course assessment and other clinician parameters.

For this study, subjects were classified as having chronic depression if they had been rated as having a “chronic” lifetime course of depression as opposed to “remitting” or “frequent/brief” depressive episodes.

Statistical Analysis

Interrater reliability for the chronicity assessment between first and second best-estimate diagnostic reviewers was assessed with Cohen’s coefficient of reliability (kappa). Student’s t test was used to compare probands and depressed relatives as well as chronically depressed and nonchronically depressed subjects on differences in age at time of interview, age at first major depressive episode, longest major depressive episode (days), total number of major depressive episodes, and number of years ill (years since first major depressive episode). Pearson’s chi-square was used to test group differences in gender and to assess possible correlates of chronicity (substance abuse, history of panic disorder, and history of suicide attempt) in subjects with and without chronic depression.

Family aggregation of chronicity was assessed using Pearson’s chi-square to compare families of chronic probands and families of nonchronic probands in terms of diagnosis of chronicity in at least one other relative and in at least one sibling. The generalized estimating equation model was used to assess the degree to which chronicity in a proband predicted chronicity in all the proband’s affected first-degree relatives and in affected siblings only. The generalized estimating equation is an analysis of clustered data that uses logistic regression but also takes into account potential correlation between observations when multiple members of the same family are considered (18) . These two analyses were carried out first for any first-degree relative, and then again for siblings only, to compare differences between generations possibly due to differential recall of illness details between generations, a generational cohort effect, or other intergenerational factors, such as differences in shared environment. Additionally, the generalized estimating equation analyses were carried out with the sample stratified for probands by preadolescent onset of illness (defined as onset before age 13) versus later onset (age 13 or older).

Results

In the families of 638 probands, a total of 1,085 first-degree relatives had a history of major depressive episode: 884 siblings, 148 parents, and 53 children. Table 1 summarizes characteristics of the illness course for the probands and for their relatives with depression. In the 638 families, 226 (35.4%) probands had a depressive illness characterized by chronicity, and these probands had a total of 352 first-degree relatives with a history of a major depressive episode; the remaining 412 probands had a total of 733 affected first-degree relatives. Among all relatives, 281 (25.9%) met the criterion for chronicity.

Interrater reliability for the designation of chronicity was good, with 87.5% agreement on subjects’ chronicity status between first and second best-estimate diagnosticians (kappa=0.74).

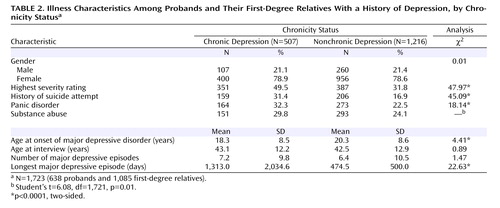

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the illness course among probands and first-degree relatives. There were no significant differences in the gender ratio or age at the time of interview between the two groups. The mean illness onset age was 2 years younger in subjects with chronicity than in those without chronicity. Those with chronic illness were nearly twice as likely to have attempted suicide, somewhat more likely to have a diagnosis of panic disorder, and slightly more likely to have a substance use diagnosis.

When the family was used as the unit of analysis, chronicity in family members was associated with proband chronicity. Of the 226 probands with chronicity, 111 (49.1%) had at least one first-degree relative with chronicity, compared with 120 (29.1%) of the 412 probands without chronicity (odds ratio=2.35, SE=0.40, Pearson’s χ 2 =25.28, p<0.0001). With the analysis limited to siblings only, 101 (44.7%) of the probands with chronicity had at least one sibling with chronicity, compared with 120 of the 412 (29.1%) probands without chronicity (odds ratio=1.97, SE=0.34, Pearson’s χ 2 =15.69, p<0.0001).

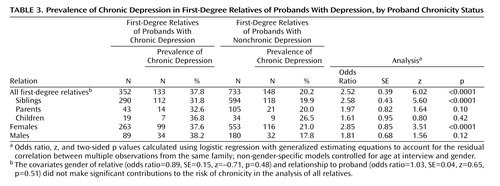

A more robust analysis used the generalized estimating equation model to obtain an odds ratio for chronicity in probands predicting chronicity in family members while controlling for age at interview and for gender ( Table 3 ). In the 638 families, 226 probands who had chronic depression had a total of 133 first-degree relatives with chronicity (out of 352 with a history of a major depression, or 37.8%), compared with the 412 remaining probands, who had a total of 148 first-degree relatives with chronicity (out of 733 with a history of major depression, or 20.2%) (odds ratio=2.52, z=6.02, p<0.0001). Additional subgroup analyses by relation to proband and by gender showed significant effects in siblings and in females, the two categories that constituted the bulk of the sample. Although subjects who were interviewed by telephone were more likely to have been rated as having chronic illness than those interviewed in person (40.8% versus 25.9%), when interview type for relatives was entered into the generalized estimating equation model, it was not a significant predictor of relatives’ chronicity (odds ratio=0.807, SE=0.14, z=–1.23, p=0.218).

When the sample was stratified by probands’ illness onset age into groups with preadolescent onset and with later onset, the familial clustering of chronicity was much stronger for the early-onset probands than for the later-onset probands. The 58 probands with preadolescent onset chronic depression had a total of 44 first-degree relatives with chronicity (out of 90 with a history of major depression, or 48.9%), whereas the 69 probands with preadolescent onset of nonchronic depression had 17 relatives with chronicity (out of 124 with a history of major depression, or 15.9%) (odds ratio=6.17, z=5.35, p<0.0001). In contrast, the 168 probands with a later onset of chronic depression had a total of 89 first-degree relatives with chronicity (out of 262 with a history of major depression, or 34.0%), whereas the 343 probands with a later onset of nonchronic depression had a total of 131 first-degree relatives with chronicity (out of 609 with a history of major depression, or 21.5%) (odds ratio 1.93, z=3.72, p=0.0022). The relative’s familial relationship to the proband (sibling, parent, or child of the proband), gender, and age at interview made no significant contribution to their risk of chronicity ( Table 4 ).

The association of chronicity with earlier onset, attempted suicide, panic disorder, and substance use disorders suggests that chronicity is related to illness severity. Indeed, we found that subjects with chronic illness were significantly more likely than those with nonchronic illness to have high best-estimate lifetime severity ratings ( Table 2 ). However, when a covariate for the severity of the proband’s illness was entered into the generalized estimating equation model along with the proband’s chronicity status, the proband’s illness severity did not significantly predict relatives’ chronicity status. Neither did the proband’s chronicity status predict relatives’ illness severity when the proband’s illness severity was included in the model.

Discussion

We found evidence that illness chronicity in probands with recurrent, early-onset major depressive disorder predicts a higher rate of chronicity among first-degree relatives than is seen among relatives of probands with episodic illness. This was true when all first-degree relatives were analyzed and when only siblings were considered. Stratification of the sample according to preadolescent or later onset in the probands revealed that the pedigrees of probands with preadolescent-onset depression showed particularly strong clustering of chronicity, although clustering of chronicity was also found in families of probands with a later illness onset.

We also found that subjects with chronic illness had an earlier onset age and higher rates of attempted suicide, panic disorder, and substance use disorders than those with episodic illness. These findings support the hypothesis that a chronic course of illness defines a subtype of major depressive disorder that is familial, more severe, and possibly indicative of a less complex genetic architecture than the broader category of major depressive disorder, especially if onset occurs before adolescence.

One of our study’s strengths is the rigorousness of the assessment of the subjects, who were directly interviewed with a well-validated instrument (the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies). Another is robustness of our findings as a result of our substantial sample size. Lifetime chronicity was a characteristic of depressive illness that could be reliably assessed by trained clinicians with access to the results of a detailed clinical interview, treatment records, and information from other family members. Liability to chronicity was shown to be distinct from liability to depression severity and appears likely to be distinct from a general liability to depression.

Comparison of our results with those of previous studies of chronic depressive conditions is complicated by the varying definitions of chronic depression in use. Because individuals with chronic depressive symptoms usually have a waxing and waning pattern of symptom severity over many years (11 , 19) , their clinical condition often meets DSM criteria for different disorders at different times. A study that examined patients with chronic depressive illness on a broad range of demographic, psychosocial, and clinical variables (20) found few differences between subjects in four subcategories of chronic depression based on DSM criteria: chronic major depressive episode (2 years’ duration), recurrent major depressive disorder without full interepisode recovery, major depressive episode superimposed on dysthymic disorder, and chronic major depressive episode with dysthymic disorder. The study’s authors suggested that “chronic depression should be viewed as a single broad condition” (20) . Although we did not similarly compare differing definitions of chronicity, we did derive meaningful results while using a single broad definition of lifetime chronicity.

The overall rate of chronicity observed in our sample, 29.4%, is somewhat higher than rates seen in previous studies. In a 12-year prospective study of patients with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, Judd et al. (11) found that 22.6% were never completely free of depressive symptoms over the entire course of the study. Uebelacker et al. (19) found that 17% of patients hospitalized with major depressive disorder were never asymptomatic during 18 months of follow-up. Our higher rates may be explained by the criteria we used to guide diagnosticians in assigning a designation of chronicity: we required that subjects have symptoms only “most of the time” rather than all of the time. Another possibility is that by selecting for recurrence and early onset in our sample, we may have selected for greater chronicity. The correlation we found between chronicity and onset age supports this hypothesis. We also found a slightly higher rate of chronicity in probands than in relatives, a difference perhaps attributable to ascertainment effects, as probands recruited into genetic studies are often more severely ill than their affected relatives.

Our finding that chronic depression is associated with several aspects of greater illness severity is consistent with reports from prior studies. In a retrospective analysis of patients with treatment-resistant depression, Crown et al. (21) found that these patients were more likely to be diagnosed as having substance abuse and anxiety disorders. In a 5-year prospective study comparing the illness course and outcome among subjects with dysthymic disorder and subjects with episodic major depressive disorder, Klein et al. (22) found that 19% of the dysthymic subjects had attempted suicide, whereas none of the subjects with episodic major depressive disorder had. Studies have also consistently shown that chronic depression results in substantial psychosocial and socioeconomic disability (23) .

Our data on familial aggregation add to the findings of the few previous family studies of individuals with chronic depressive illness. As noted earlier, several studies have found evidence for familiality of dysthymia. One of these studies (14) , however, found only limited evidence of familiality of chronic major depression, with chronicity defined by the duration of a single episode. This may have been because the study analyzed subjects with dysthymia and with chronic depression separately, possibly diluting the study’s statistical power to detect family clustering of depressive conditions characterized by chronicity. In addition, the lowering of DSM’s duration requirement of major depressive symptoms to 1 year in the probands may have resulted in inclusion of phenocopy cases of “chronic” depression subjects in the analyses. Finally, a definition of chronic major depression that is based on the duration of a single episode may not yield a familial phenotype.

Our finding that the relatives of probands with chronic, preadolescent-onset depressive illness have a particularly increased risk of chronic depression adds to findings reported by Wickramaratne et al. (15) , who evaluated individuals 10 to 15 years after they had been diagnosed with either prepubertal (Tanner stages 1 or 2) or adolescent-onset (Tanner stages 3 or 4) major depressive disorder to determine whether familial risk varies with onset age, recurrence, or continuity of illness into adulthood. They found that the rates of major depressive disorder were higher in the relatives of prepubertal-onset probands than in the relatives of adolescent-onset probands only in the subset of probands with recurrent illness and in those who had continuity of their illness into adulthood. While chronicity per se was not being investigated in the study, recurrence and persistence of illness symptoms for years after initial diagnosis are certainly features of chronicity, and these features predicted greater familial rates of major depressive disorder in their sample. In our sample, rates of major depressive disorder in relatives could not be determined because only affected relatives were included. However, our finding that preadolescent onset and chronicity in probands predicted greater chronicity in relatives supports the importance of the distinction between probands with preadolescent and with later illness onset in family studies of depression.

Our findings should be viewed in light of several limitations. First, although our data included available treatment records and information from family members, most of the information about a subject’s course of illness was derived from a single cross-sectional interview, with the chronicity data gathered retrospectively. The assessment of lifetime course in the interview was based on the unstructured illness-overview portion of the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies, which does not include questions that systematically address lifetime course. However, the interrater reliability for the chronicity assessment between first and second best-estimate reviewers was good. Second, we did not gather data on any of the environmental variables that have been associated with chronicity, such as early childhood adversity from sexual and physical abuse or parental neglect (12 , 24) . These could constitute aspects of shared familial environment that might partly explain our finding of familial aggregation of chronicity. Third, we did not have data to identify the physiological onset of puberty in our subjects. Thus our designations of preadolescent and later onset are based on a cutoff of age 13, to approximate prepubertal and postpubertal onset. Fourth, because of the predominance of siblings and females among first-degree relatives in our study, and hence the relatively small numbers of parents, children, and males, we may have had inadequate statistical power to test for familial aggregation of depression chronicity in these latter subgroups. Fifth, our data set was not ideally suited to addressing the question of whether chronicity is associated with a greater liability to depression in general, because we focused only on ascertaining first-degree relatives with a history of major depression rather than all first-degree relatives. However, if chronic depression in probands is associated with higher rates of depression in a family, it should be associated with a higher number of depressed relatives per family, assuming family sizes are equal between pedigree sets. Among families of chronically depressed probands, there were an average of 1.52 depressed first-degree relatives, whereas for the nonchronic proband families, the average was 1.76.

This study, along with prior findings, suggests that illness chronicity may identify a clinical subtype of depressive disorders that reduces genetic heterogeneity in major depressive disorder and that the use of a chronicity variable may inform future genetic studies of the disorder. Alternatively, the interaction of genetic factors and shared familial environmental factors, such as early childhood adversity, might explain our findings (25) . Further refinement of the definition of chronicity in depressive illness may increase the power of future studies.

1. Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS: Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1552–1562Google Scholar

2. Lander ES, Schork NJ: Genetic dissection of complex traits. Science 1994; 265(5181):2037–2048Google Scholar

3. Hall JM, Lee MK, Newman B, Morrow JE, Anderson LA, Huey B, King MC: Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science 1990; 250(4988):1684–1689Google Scholar

4. Potash JB, Willour VL, Chiu YF, Simpson SG, MacKinnon DF, Pearlson GD, DePaulo JR Jr, McInnis MG: The familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder pedigrees. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1258–1264Google Scholar

5. MacKinnon DF, McMahon FJ, Simpson SG, McInnis MG, DePaulo JR: Panic disorder with familial bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:90–95Google Scholar

6. Fisfalen ME, Schulze TG, DePaulo JR Jr, DeGroot LJ, Badner JA, McMahon FJ: Familial variation in episode frequency in bipolar affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1266–1272Google Scholar

7. Potash JB, Zandi PP, Willour VL, Lan T-H, Huo Y, Avramopoulos D, Shugart YY, MacKinnon DF, Simpson SG, McMahon FJ, DePaulo JR Jr, McInnis MG: Suggestive linkage to chromosomal regions 13q31 and 22q12 in families with psychotic bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:680–686Google Scholar

8. Levinson DF, Zubenko GS, Crowe RR, DePaulo RJ, Scheftner WS, Weissman MM, Holmans P, Zubenko WN, Boutelle S, Murphy-Eberenz K, MacKinnon D, McInnis MG, Marta DH, Adams P, Sassoon S, Knowles JA, Thomas J, Chellis J: Genetics of recurrent early-onset depression (GenRED): design and preliminary clinical characteristics of a repository sample for genetic linkage studies. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2003; 119:118–130Google Scholar

9. Bland RC, Newman SC, Orn H: Recurrent and nonrecurrent depression: a family study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:1085–1089Google Scholar

10. Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True W, Lin N, Meyer JM, Toomey R, Faraone SV, Merla-Ramos M, Tsuang MT: A registry-based twin study of depression in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:468–472Google Scholar

11. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, Paulus MP, Kunovac JL, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Rice JA, Keller MB: A prospective 12-year study of subsyndromal and syndromal depressive symptoms in unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:694–700Google Scholar

12. Klein DN, Riso LP, Donaldson SK, Schwartz JE, Anderson RL, Ouimette PC, Lizardi H, Aronson TA: Family study of early-onset dysthymia: mood and personality disorders in relatives of outpatients with dysthymia and episodic major depression and normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:487–496Google Scholar

13. Donaldson SK, Klein DN, Riso LP, Schwartz JE: Comorbidity between dysthymic and major depressive disorders: a family study analysis. J Affect Disord 1997; 42:103–111Google Scholar

14. Klein DN, Shankman SA, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR: Family study of chronic depression in a community sample of young adults. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:646–653Google Scholar

15. Wickramaratne PJ, Greenwald S, Weissman MM: Psychiatric disorders in the relatives of probands with prepubertal-onset or adolescent-onset major depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:1396–1405Google Scholar

16. Weissman MM, Gershon ES, Kidd KK, Prusoff BA, Leckman JF, Dibble E, Hamovit J, Thompson WD, Pauls DL, Guroff JJ: Psychiatric disorders in the relatives of probands with affective disorders. The Yale University-National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:13–21Google Scholar

17. Nurnberger JI Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, Severe JB, Malaspina D, Reich T (NIMH Genetics Initiative): Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies: rationale, unique features, and training. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:849–859Google Scholar

18. Zeger SL, Liang KY: Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 1986; 42:121–130Google Scholar

19. Uebelacker LA, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Miller IW: Characterizing the long-term course of individuals with major depressive disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004; 192:65–68Google Scholar

20. McCullough JP Jr, Klein DN, Borian FE, Howland RH, Riso LP, Keller MB, Banks PL: Group comparisons of DSM-IV subtypes of chronic depression: validity of the distinctions, part 2. J Abnorm Psychol 2003; 112:614–622Google Scholar

21. Crown WH, Finkelstein S, Berndt ER, Ling D, Poret AW, Rush AJ, Russell JM: The impact of treatment-resistant depression on health care utilization and costs. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:963–971Google Scholar

22. Klein DN, Schwartz JE, Rose S, Leader JB: Five-year course and outcome of dysthymic disorder: a prospective, naturalistic follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:931–939Google Scholar

23. Kennedy N, Paykel ES: Residual symptoms at remission from depression: impact on long-term outcome. J Affect Disord 2004; 80:135–144Google Scholar

24. Zlotnick C, Warshaw M, Shea MT, Keller MB: Trauma and chronic depression among patients with anxiety disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65:333–336Google Scholar

25. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R: Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003; 301(5631):386–389Google Scholar