Striatal Dopaminergic D2 Receptor Density Measured by [123I]Iodobenzamide SPECT in the Prediction of Treatment Outcome of Alcohol-Dependent Patients

Abstract

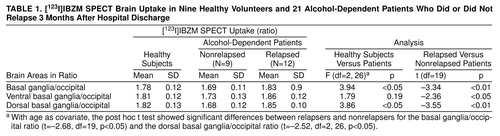

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to study striatal dopaminergic dopamine 2 (D2) receptors as a biological marker of early relapse in detoxified alcoholic patients by using [123I]iodobenzamide ([123I]IBZM) single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). METHOD: The authors performed [123I]IBZM SPECT on 21 alcohol-dependent inpatients during detoxification and on nine healthy volunteers, using the ratios of basal ganglia to occipital lobes for SPECT quantification. Depending on treatment outcome 3 months after hospital discharge, patients were determined to be relapsers or nonrelapsers. RESULTS: Alcohol-dependent subjects with early relapse (within 3 months after hospital discharge) showed a higher uptake of [123I]IBZM in the basal ganglia during detoxification (mean ratio=1.83, SD=0.9) than patients who did not have early relapse (mean ratio=1.69, SD=0.11). CONCLUSIONS: These results suggest that low levels of dopamine, or an increased density of free striatal dopaminergic D2 receptors, could be related to early relapse in alcohol-dependent patients. Therefore, [123I]IBZM SPECT could become a biological marker of vulnerability to relapse for alcoholic patients in recovery.

There is increasing evidence that dysfunction of dopaminergic transmission is involved in the pathogenesis of alcoholism. Acute ethanol administration in rats induces dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (1), an effect related to locomotor activation, reward, and compulsion to drink (2). Chronic ethanol consumption has been associated with decreased mesostriatal dopaminergic activity in rodents (3) as well as low levels of dopamine and its metabolites in alcoholic patients (4). This decrease in dopaminergic function can lead to compensatory adaptive changes of D2 dopaminergic receptors, such as hypersensitivity or increased density (5), that could be the psychobiological background of the enhanced cue-induced conditioned responses of craving or withdrawal involved in the relapse process (6, 7).

We used [123I]iodobenzamide ([123I]IBZM) single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) to study the dopaminergic system and to evaluate its potential usefulness in predicting treatment outcome in detoxified alcoholic patients.

METHOD

We recruited for study 21 patients with alcohol dependence diagnosed according to DSM-IV who were hospitalized for detoxification treatment in our addictive behavior unit. The study group included 18 men and three women, and their mean age was 43.4 years (SD=9.8). Most of the patients had a family history of alcoholism and severe alcohol dependence. Exclusion criteria were severe psychiatric or neurological disorders, drug hypersensitivity reactions, pregnancy, having received dopaminergic agonists or antagonists during the last month, and meeting DSM-IV criteria for substance disorder involving substances other than alcohol, nicotine, or caffeine during the last 6 months. The comparison group comprised nine healthy volunteers who had been screened for lack of drug (except nicotine and caffeine) or alcohol abuse. Four of the comparison subjects were men and five were women; their mean age was 39.1 (SD=8.2). Exclusion criteria were the same as those used for the alcohol-dependent group. The study was approved by the local authorities. Written informed consent was obtained in all cases.

Alcohol-dependent subjects were hospitalized for 14 days. They received tapering doses of clomethiazol and B vitamins for detoxification during the first 7–9 days. [123I]IBZM SPECT was performed on hospital days 8 to 10. Patients then entered an outpatient care program with the goal of abstinence. Outcome was assessed by recording drinking status as abstinence or relapse at 3 months after hospital discharge. Relapse criteria were more than four drinks/day, more than 4 days drinking/week, or situations requiring a new detoxification treatment.

SPECT acquisition was started 90 minutes after intravenous injection of 185 MBq of [123I]IBZM; a GEMS Helix gammacamera was used. Free striatal D2 dopaminergic receptor density was estimated by basal ganglia/occipital ratios. A region of interest including the whole striatum was used for the global basal ganglia/occipital ratio, and two smaller regions of interest were used to evaluate the ventral and dorsal regions of the striatum separately (ventral basal ganglia/occipital and dorsal basal ganglia/occipital ratios). Intraobserver variability of the SPECT quantification method (8) was assessed in the comparison group, and linear associations (r=0.93–0.99, N=9, p<0.01) and similar distributions between both sets of data were found for all regions of interest and ratios.

For statistics, unpaired Student’s t test, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with age as a covariate, post hoc t test, Pearson’s product-moment correlation, and chi-square test with Yates’s continuity correction were applied. All tests were two-tailed, and a significance level of 0.05 was adopted.

RESULTS

The comparison group and the alcohol-dependent group did not differ in age (t=1.15, df=28, p=0.26), sex (χ2=3.57, df=1, p=0.06), or caffeine use (t=0.79, df=28, p=0.44). They differed only in nicotine use (t=2.67, df=28, p<0.05), but Pearson’s correlation did not show any relationship between nicotine consumption and basal ganglia/occipital ratios (r=0.042, N=30, p=0.98).

Nine of the alcohol-dependent patients did not relapse during the 3-month period; 12 relapsed. These two groups did not differ in age; the mean age of the nonrelapsed patients was 46.8 years (SD=10), and that of the relapsed patients was 40.9 years (SD=10) (t=1.38, df=19, p=0.18). They also did not differ in sex (χ2=0.07, df=1, p=0.79), nicotine use (t=–0.26, df=19, p=0.79), caffeine use (t=–0.83, df=19, p=0.41), alcohol use (t=0.18, df=19, p=0.86), duration of alcohol abuse (t=0.63, df=19, p=0.54), age at onset of alcohol dependence (t=0.58, df=19, p=0.57), or number of previous detoxifications (t=–1.62, df=19, p=0.13).

An age-related decline in IBZM uptake was found both in the comparison group (F=38.00, df=1, 7, p<0.0005) and in the group of alcohol-dependent patients (F=10.31, df=1, 19, p=0.005).

The ANCOVA showed a significant group effect for the basal ganglia/occipital and the dorsal basal ganglia/occipital ratios in the comparison group and in the two subgroups of alcohol-dependent patients (relapsers and nonrelapsers). Post hoc t tests showed that alcoholic patients who relapsed had significantly higher basal ganglia/occipital and dorsal basal ganglia/occipital ratios than patients who did not. Considering only the alcohol-dependent sample, we found significant differences in all ratios between relapsed and nonrelapsed patients (table 1).

IBZM uptake did not differ between the comparison group and the whole group of alcohol-dependent patients in any striatal region (global: t=–0.20, df=28, p=0.85; ventral: t=–0.08, df=28, p=0.94; dorsal: t=–0.79, df=28, p=0.44).

DISCUSSION

In this study, alcohol-dependent subjects who relapsed during the first 3 months after hospital discharge showed a higher binding of [123I]IBZM in the whole striatum between days 8 and 10 of detoxification than those who did not. Therefore, alcoholic patients who relapse early may have a higher D2 dopaminergic receptor density or lower levels of synaptic dopamine in the striatum than alcoholic patients who do not relapse early. Both decreased dopaminergic activity (3, 4) and an adaptive increase during withdrawal (5, 9) in the number of D2 dopaminergic receptors have been suggested in alcoholic patients, pointing to a different adjustment of dopaminergic function depending on treatment outcome.

We found no differences in D2 dopaminergic receptor availability when we compared the whole group of alcoholic patients with the nonalcoholic subjects. Two studies using positron emission tomography have reported reductions in D2 dopaminergic receptor availability in alcoholics (10, 11), but no distinction of treatment outcome was specified.

Our results suggest that low levels of dopamine, or an increased density of free striatal D2 dopaminergic receptors, could be related to early relapse. Therefore, [123I]IBZM SPECT could become a biological marker of vulnerability to relapse in alcoholic patients during recovery. Further confirmation of these results could better address the design of specific pharmacological treatments for alcoholic patients with a high vulnerability to relapse.

Received April 15, 1998; revisions received Jan. 7 and May 6, 1999; accepted May 13, 1999. From the Departments of Psychiatry (Addictive Behavior Unit) and Nuclear Medecine, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau; and the Departament de Psiquiatria i Medicina Legal, Universitat Autñ®a de Barcelona, Spain. Address reprint requests to Dr. Guardia, Unidad de Conductas Adictivas, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, C/San Antonio Marì Claret 167, 08025, Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grant 97/1158 from the Fondo de Investigaciò¬¬inisterio de Sanidad and by the Institute of Research of Santa Creu i Sant Pau Hospital, Barcelona.

|

1. Di Chiara G, Imperato A: Ethanol preferentially stimulates dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats. Eur J Pharmacol 1985; 115:131–132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Yoshimoto K, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK: Ethanol enhances the release of dopamine and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens of HAD and LAD lines of rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1992; 16:781–785Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Diana M, Pistis M, Muntoni A, Gessa G: Mesolimbic dopaminergic reduction outlasts ethanol withdrawal syndrome: evidence of protracted abstinence. Neuroscience 1996; 71:411–415Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Fulton MK, Kramer G, Moeller FG, Chae Y, Isbell PG, Petty F: Low plasma homovanillic acid levels in recently abstinent alcoholic men. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1819–1820Google Scholar

5. Rommelspacher H, Raeder C, Kaulen P, Br�G: Adaptive changes of dopamine-D2 receptors in rat brain following ethanol withdrawal: a quantitative autoradiographic investigation. Alcohol 1992; 9:335–362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Robinson TE, Berridge KC: The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1993; 18:247–291Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Satel SL, Kosten TR, Schuckit MA, Fischman MW: Should protracted withdrawal from drugs be included in DSM-IV? Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:695–704Google Scholar

8. Verhoeff NP, Kapucu O, Sokole-Busemann E, van Royen EA, Janssen AG: Estimation of dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in the striatum with iodine-123-IBZM SPECT: technical and interobserver variability. J Nucl Med 1993; 34:2076–2084Google Scholar

9. Heinz A, Lichtenberg-Kraag B, Baum SS, Gr㤠K, Kr�, Dettling M, Rommelspacher H: Evidence for prolonged recovery of dopaminergic transmission after detoxification in alcoholics with poor treatment outcome. J Neural Transm Gen Sect 1995; 102:149–157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hietala J, West C, Syvã«¡hti E, Nagren K, Lehikoinen P, Sonninen P, Ruotsalainen U: Striatal D2 dopamine receptor binding characteristics in vivo in patients with alcohol dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994; 116:285–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, Pappas N, Shea C, Piscani K: Decreases in dopamine receptors but not in dopamine transporters in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1996; 20:1594–1598Google Scholar