Three-Year Outcomes of Maintenance Nortriptyline Treatment in Late-Life Depression: A Study of Two Fixed Plasma Levels

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study compared the long-term efficacy of two fixed plasma levels of nortriptyline in preventing or delaying recurrence of major depression in elderly patients and in minimizing residual depressive symptoms and somatic complaints. METHOD: The authors randomly assigned 41 elderly patients with histories of recurrent major depression to 3-year, double-blind maintenance pharmacotherapy using nortriptyline, with controlled plasma concentrations of 80–120 ng/ml versus 40–60 ng/ml. The authors compared times to, and rates of, recurrence of major depression. They also compared frequencies of side effects, noncompliance episodes, and subsyndromal symptomatic flare-ups. RESULTS: Major depressive episodes recurred for six (29%) of 21 subjects in the 80–120-ng/ml condition and eight (40%) of 20 subjects in the 40–60-ng/ml condition, a nonsignificant difference. Most recurrences took place in the first year of maintenance treatment. Hamilton depression scores in the subsyndromal range (higher than either 10 or 7) occurred significantly more often at 40–60 ng/ml, while constipation occurred significantly more often at 80–120 ng/ml. The proportions of patients reporting missed doses did not differ. CONCLUSIONS: Maintenance pharmacotherapy with nortriptyline at 80–120 ng/ml is associated with fewer residual depressive symptoms, that is, a less variable long-term response, than pharmacotherapy at 40–60 ng/ml, but constipation is more frequent and there is no difference in recurrence of syndromal major depressive episodes. Treatment at 80–120 ng/ml may be preferable, because of fewer residual symptoms and less variability of response, as long as side effect burden can be managed successfully.

The goal of this study was to determine whether elderly depressed patients who cannot sustain a remission without antidepressant medication must be maintained at full acute-treatment dose. In other words, is the effective prophylactic dose the same as the effective acute-treatment dose? Thus, we compared the efficacy of two fixed plasma levels of nortriptyline (80–120 ng/ml and 40–60 ng/ml) in preventing or delaying recurrences of major depression in the elderly. The pool of subjects available for this study consisted of patients who had experienced a recurrence of major depression while in a placebo maintenance condition in our recently completed study of nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance treatments in late-life depression (1).

If elderly patients can remain well with a lower dose than that used during acute therapy, this might confer three advantages in their long-term management: 1) fewer side effects, 2) better compliance because of diminished discomfort, and 3) enhanced margin of safety in the face of supervening medical illnesses. On the other hand, however, if patients suffer higher rates of recurrence and/or more symptom exacerbations or minor episodes (i.e., a more brittle response) in a maintenance condition with a reduced blood level, this information would also be critical for long-term clinical management. Either finding would have value for clinical practice.

The critical issue is that the goal of long-term treatment in old-age depression is to maintain the patient in an episode-free state or at least to attenuate recurrences so that they do not interfere significantly with work, social functioning, or quality of life. Successful prevention may involve other important gains for the elderly, including reduced risk for suicide, increased stability of mood during interepisode intervals, renewed self-esteem and hope for the future, improved family and social relations, better compliance with nonpsychiatric medical therapies, and reduction in chronic disability (related to medical illness) that would otherwise be amplified by depression (2). The particular vulnerability of elderly depressed patients in terms of general psychosocial fragility, multiple medical diagnoses, risk for suicide, and polypharmacy support the need for an especially careful assessment of long-term maintenance dose levels.

The current study extends to old age our earlier comparison of full-dose versus half-dose pharmacotherapy in the maintenance treatment of recurrent depression in midlife (3). In the midlife study we established the dose of imipramine necessary to treat the patient during acute treatment and then administered that dose or half of that dose, depending on random assignment during maintenance treatment. In the study reported here, we used a two-tiered, fixed-plasma-level design contrasting 80–120 ng/ml and 40–60 ng/ml. The midlife study suggested that superior prophylaxis could be achieved with a maintenance strategy using the same dose of the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine as was used during acute therapy. Similar conclusions had been reached by Prien et al. (4) and by Gelenberg et al. (5). Our primary hypotheses were as follows:

1. Patients in the 40–60-ng/ml maintenance condition would experience a higher rate of recurrences than those in the 80–120-ng/ml condition.

2. Time to recurrence would be shorter in the 40–60-ng/ml condition.

3. Patients in the 40–60-ng/ml condition would experience a greater frequency of depressive symptoms, that is, a more brittle long-term response.

4. Patients in the 40–60-ng/ml condition would experience fewer and less severe side effects.

5. Because of fewer side effects, patients in the 40–60-ng/ml condition would show higher rates of compliance.

METHOD

We had projected that 54 subjects would be available and consent to participation in this study. Fifty-three subjects became eligible, of whom six refused to participate, four failed to respond to restabilization treatment, and two dropped out because of intercurrent medical problems. Thus, we were able to recruit a total of 41 subjects, of whom 21 were assigned randomly to 3 years of maintenance pharmacotherapy with nortriptyline at 80–120 ng/ml and 20 to maintenance at 40–60 ng/ml. As noted in the introduction, these were subjects who had experienced a recurrence of major depression after random assignment to a placebo maintenance condition in the parent study (1). Nine subjects in each of the two conditions had been receiving monthly maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy plus placebo in the parent study, while the remaining subjects had received placebo in a medication clinic (without interpersonal psychotherapy). After experiencing a recurrence of major depression, patients were treated openly until remission by means of combined treatment with nortriptyline and weekly interpersonal psychotherapy, as we have described elsewhere (6). After remission of their recurrent episodes, the patients entered continuation treatment for an additional 16 weeks to ensure stability of remission, defined as a score of 10 or less on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (7) over the 16-week period of observation. We asked patients whose remissions were stable to provide written informed consent, using approved institutional review board procedures, for participation in the study, that is, to be randomly assigned on a double-blind basis to one of two conditions in a second maintenance trial whose goal was to compare the relative efficacy of two fixed plasma levels of nortriptyline in preventing or delaying recurrence of major depression.

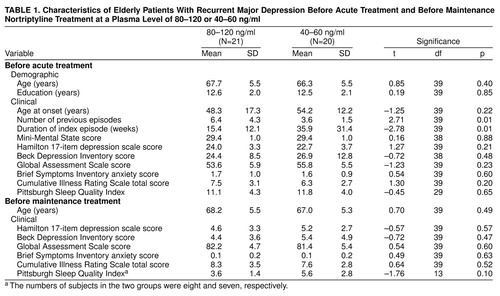

Of the 21 patients with plasma levels of 80–120 ng/ml and the 20 patients with levels of 40–60 ng/ml, approximately one-fifth in each group were male (four in each group) and nearly all were white (18 and 19, respectively). Five and 12, respectively, were married, a statistically significant difference (χ2=5.53, df=1, p=0.02). Table 1 summarizes other demographic and clinical attributes of the subgroups at two time points: before treatment in the parent study (top of table) and after restabilization but before random assignment in the plasma-level study (bottom). The groups did not differ on most measures that could have affected outcomes, with the exception of a greater number of lifetime episodes of major depression in the patients randomly assigned to the higher plasma level. This difference could have made it more difficult to detect a treatment effect in favor of the 80–120-ng/ml condition, since the greater number of prior episodes might confer greater liability to recurrence. The subgroups did not differ on measures of depressive or anxiety symptom severity at the point of assignment to maintenance treatment. Nor did they differ in the duration of acute-phase treatment needed to restabilize their conditions, that is, to bring about remission. The mean duration of acute-phase restabilization treatment among the patients subsequently randomly assigned to 80–120 ng/ml was 8.4 weeks (SD=9.2), as compared with 9.1 weeks (SD=9.4) for the patients at the 40–60 ng/ml plasma level (t=0.23, df=39, p=0.82). More of the subjects at the higher level required the use of adjunctive medication (i.e., lorazepam, lithium, or perphenazine) to achieve restabilization than did subjects at the lower level: eight (38%) of 21 (95% confidence interval [CI], 17%–59%) versus two (10%) of 20 (95% CI, 0%–23%) (p=0.07, Fisher’s exact test). Lithium and perphenazine treatments were discontinued before the patients were allowed to enter continuation-phase treatment, and use of lorazepam was minimized (0.5–2.0 mg/day). The groups did not differ in the proportion of subjects who relapsed during continuation treatment before random assignment; only one subject in each group suffered a relapse, and both of these patients were successfully restabilized.

For the patients randomly assigned to the lower nortriptyline plasma level, we gradually decreased the dose over 4 weeks by 10 mg/week on average. The average daily dose of nortriptyline for patients at the higher plasma level was 72.4 mg (SD=23.1), and for patients at the lower plasma level it was 48.5 mg/day (SD=29.1). The average nortriptyline blood levels in the two conditions during maintenance were 97.9 ng/ml (SD=12.3) and 51.6 ng/ml (SD=8.7). An open monitoring committee, consisting of a co-principal investigator (J.M.P.) and co-investigator (C.C.), monitored doses and blood levels during double-blind maintenance treatment to ensure that the blood concentrations remained within the specified ranges for the two conditions (80–120 ng/ml and 40–60 ng/ml, respectively).

Clinical practice has generally been to lower by one-third to one-half the dose used during acute therapy for purposes of maintenance treatment (8, 9). We considered using steady-state levels below 40 ng/ml but thought that this approach might result in an ultra-low or ineffective dose. On balance, it seemed to us both safer and more ethical to accept a minimum value of 40 ng/ml with a range to 60 ng/ml in the lower-dose group, based on a range of steady-state concentrations for full-dose recipients of 80–120 ng/ml.

The maintenance therapy sessions followed a medication-clinic format, with no psychotherapy provided (10). In this regard, the geriatric study differed from the earlier midlife study (3), during the second maintenance phase of which patients continued to receive either maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy or medication-clinic management, depending on their nonpharmacologic treatment assignment in the parent protocol. Our rationale for using medication-clinic management for all patients was to simplify the design of the study and to avoid the potential confound of having more interpersonal psychotherapy patients in one dose condition than the other. The patients attended the clinic once every 4 weeks, with more frequent visits as needed for increases in symptoms or adverse reactions to medications. The patients met with their primary clinicians and supervising psychiatrists for 20–30 minutes. Maintenance therapy lasted 3 years or until recurrence of major depression, whichever occurred first. All maintenance therapy sessions were audiotaped and rated to ensure therapist adherence to the medication-clinic format and an absence of specific psychotherapeutic elements. The monitoring of compliance consisted of 1) pharmacist pill counts on each visit, 2) psychiatrist interview, and 3) continuous monitoring of dose-to-level ratios. During maintenance, blood levels of nortriptyline were monitored monthly in order to ensure continued treatment compliance. Analyses of nortriptyline, together with the corresponding 10-hydroxy metabolites, were performed by one of the co-principal investigators (J.M.P. or B.G.P.) by using methods previously published (11). These methods use high-performance liquid chromatography with a limit of detection of 5–10 ng/ml for nortriptyline and its metabolites.

In the event of reappearance of symptoms during maintenance therapy, the patient was seen within 2 days by the treating clinician and psychiatrist. The patient was observed and evaluated twice within 7 days and judged to be in an episode of major depression if he or she met the Research Diagnostic Criteria (12) for major depressive episode over a 2-week period and had a score of 17 or higher on the 17-item Hamilton depression scale (7). The severity criterion of 17 on the 17-item Hamilton scale was identical to that used in the definition of the index episode (1). An independent confirmation of recurrence by a senior psychiatrist blind to treatment assignment was also necessary.

The basic analytic approach for comparing the times to and rates of recurrence was Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank statistic (13). Rates of recurrences were compared with Fisher’s exact test for 2×2 tables (14). We anchored our analyses from the point of random assignment and not from the time of the first maintenance clinic visit 1 month later.

Five subjects were still in active treatment at the time of the final outcome analysis. Of these, three subjects (two in the 80–120-ng/ml condition and one in the 40–60-ng/ml condition) were in their third year of maintenance treatment, and two subjects (one in each cell) were in their second year at 60 weeks. Those subjects became censored observations in the survival analysis.

RESULTS

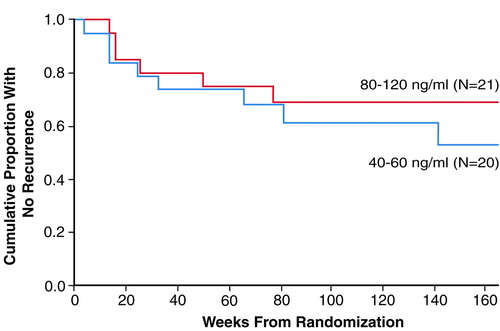

As can be seen in Figure 1, there was no significant difference between the survival curves for the two treatment arms. Recurrences were experienced by six (29%) of the 21 patients (95% CI, 10%–48%) in the 80–120-ng/ml condition and eight (40%) of the 20 subjects (95% CI, 19%–61%) in the 40–60-ng/ml condition (p=0.52, Fisher’s exact test). As indicated in Table 2, most recurrences in either treatment arm took place during the first year of maintenance therapy. A total of five subjects receiving nortriptyline at the higher plasma level terminated treatment for reasons other than recurrence (one refused further treatment, one was noncompliant, one developed a medical problem contraindicating further participation, one died, and one became psychotic). Four of the subjects at the lower plasma level terminated treatment for reasons other than relapse or recurrence (one refused further treatment, two had medical problems, and one had side effects).

We tested the hypothesis of more frequent symptom “flurries” in patients at the lower plasma level by examining the proportion of Hamilton depression ratings that were above 10 and above 7 during maintenance treatment. The median percentage of Hamilton ratings per subject that were above 10 was 6% (range=0%–67%) in the high-level subjects and 25% (range=0%–100%) in the low-level subjects (χ2=3.81, df=1, p=0.05). Similarly, the median percentages of ratings above 7 were 13% (range=0%–100%) and 43% (range=0%–100%) at the higher and lower plasma levels, respectively (χ2=4.54, df=1, p=0.04). Thus, Hamilton depression ratings in the subsyndromal range occurred more frequently among subjects receiving maintenance nortriptyline at the lower plasma level.

In order to test whether the presence of more residual symptoms was associated with greater functional impairment, we inspected measures from the Global Assessment Scale (15) and the Inventory of General Life Functioning (16) during maintenance treatment. Scores on these measures appeared to be overlapping, without clear-cut differences.

A higher proportion of subjects in the 80–120 ng/ml condition complained of persistent and bothersome constipation: seven (33%) of 21 (95% CI, 13%–53%) versus one (5%) of 20 (95% CI, 0%–15%) (p=0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Within the subjects with plasma levels of 80–120 ng/ml we observed no relationship between steady-state nortriptyline level and the presence or absence of constipation. Given the almost complete absence of this complaint among patients in the 40–60-ng/ml condition, it appeared that the threshold for this complaint lay between 60 and 80 ng/ml. No other atropinic side effects (dry mouth or urinary hesitance) rated by the Åsberg Side Effect Rating Scale (17) differed between the two arms. Equal proportions of subjects in both arms received bethanechol for constipation or dry mouth (25%–29%), and equal proportions received stool softeners (30%–43%). Subjects did not differ in average pulse rate during maintenance (80–120 ng/ml—79.1 bpm, SD=6.3; 40–60 ng/ml—80.8 bpm, SD=12.0) or in weight gain during maintenance (80–120 ng/ml—4.1 lb, SD=10.0; 40–60 ng/ml—3.6 lb, SD=17).

Finally, we were unable to detect a difference in compliance rates between the two treatment arms. Missing at least one dose of medication during maintenance treatment was reported by 13 (62%) of the 21 patients at the higher plasma level (95% CI, 41%–83%) and 16 (80%) of the 20 patients at the lower plasma level (95% CI, 62%–98%) (n.s.).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this is the first double-blind, randomized, concentration-controlled trial of maintenance antidepressant pharmacotherapy in geriatric depression. Our data indicate successful implementation of the protocol’s required blood-level ranges in the two plasma-level conditions. We observed that long-term treatment response was somewhat more variable or unstable in patients receiving lower doses of nortriptyline, as evidenced primarily by a higher frequency of Hamilton depression scores in the mildly depressed range, but not by a greater rate of recurrence of syndromal major depression. In this study, lower-dose treatment actually straddled steady-state plasma levels in the lower therapeutic range for nortriptyline. This is a key point of difference from our imipramine full-dose/half-dose study of midlife patients, in which subjects assigned to the half-dose condition had a combined blood level (imipramine plus desipramine) of 147.7 ng/ml (SD=79.8), well below the usually accepted therapeutic plasma level of 225 ng/ml. In the midlife study (3) we observed recurrence rates of 70% in the half-dose condition and 30% in the full-dose condition. The recurrence rates of 29% and 40% observed in the geriatric two-tiered, fixed-plasma-level study are similar to the 43% rate of recurrence observed in the parent study for nortriptyline delivered in the context of medication-clinic treatment at doses sufficient to bring about plasma steady-state levels of 80–120 ng/ml, and these rates are clearly superior to the recurrence rate of 90% observed for patients receiving placebo plus medication clinic (18).

More of the subjects with higher plasma levels (eight of 21, 38%) than those with lower plasma levels (two of 20, 10%) had required adjunctive medication during the acute phase of treatment (χ2=4.39, df=1, p=0.04). Four of the six subjects who suffered recurrences at the higher plasma level had required augmented pharmacotherapy with lithium or perphenazine for the initial response, as compared with two of the 12 subjects at the lower level who did not experience a recurrence. While this difference is not statistically significant (p=0.11, Fisher’s exact test), it raises the possibility that we underestimated the efficacy of full-dose treatment, given the chance bias in randomization with regard to initial augmented pharmacotherapy. The observed difference in recurrence rate between 29% and 40% is small and probably not an important difference to detect clinically; 80% power would be achieved only when the numbers of subjects are very large, i.e., 290 per group. One additional potential problem in the randomization is that patients at the plasma level of 80–120 ng/ml may have had a higher risk of relapse based on a higher number of prior episodes.

The protocol required all subjects participating in this study to have recurrent unipolar major depression. Thus, the study group consisted of patients who were at particularly high risk for recurrence. It is possible that the contrast between the two treatment arms would have been greater in a more heterogeneous group. With respect to the implications of this trial for long-term patient management, the individual risk-benefit ratio must be considered. For some, perhaps most, elderly patients the disruptive effects of even subsyndromal levels of depressive symptoms on quality of life will indicate the use of full-dose maintenance treatment. The side effect burden of nortriptyline in the elderly is generally mild, but the trade-off of fewer depressive symptoms and more side effects needs to be taken into account. Almost one-third of our patients (in either condition) required the use of supportive countermeasures, such as bethanechol or stool softeners, to ease the burden of nortriptyline’s atropinic side effects. This observation adds to the importance of testing other, better-tolerated antidepressants for their long-term efficacy in old age. Also, the more variable or unstable level of depressive symptoms seen in the 40–60-ng/ml condition requires further assessment with respect to associated functional impairment, impact on sense of well-being, cost-effectiveness, and liability for eventual relapse and recurrence (9).

Received Aug. 31, 1998; revision received Jan. 4, 1999; accepted Feb. 19, 1999. From the Mental Health Clinical Research Centers for Late-Life and Mid-Life Mood Disorders, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. Reprints of this article are not available. Address correspondence to Dr. Reynolds, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Rm. E-1135, 3811 O’Hara St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213; [email protected] (e-mail) Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-52247, MH-30915, MH-43832, MH-37869, and MH-00295. The authors thank the staff of the Late-Life Depression Prevention Clinic and the Clinical Core of the Mental Health Clinical Research Center for Late-Life Mood Disorders for their care of the patients participating in this study.

|

|

FIGURE 1. Time to Recurrence Over 3 Years of Maintenance Nortriptyline Treatment for Elderly Patients With Recurrent Major Depression Who Had Plasma Levels of 80–120 or 40–60 ng/mla

Log-rank statistic=0.56, p=0.45, n.s.

1. Reynolds CF III, Dew MA, Frank E, Begley AE, Miller MD, Cornes C, Mazumdar S, Perel JM, Kupfer DJ: Effects of age at onset of first lifetime episode of recurrent major depression on treatment response and illness course in elderly patients. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:795–799Link, Google Scholar

2. Murphy E: The prognosis of depression in old age. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 142:111–119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, Cornes C, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ: Comparison of full dose versus half dose pharmacotherapy in the maintenance treatment of recurrent depression. J Affect Disord 1993; 27:139–146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Prien RF, Kupfer DJ, Mansky PA, Small JG, Uason VB, Voss CB, Johnson WE: Drug therapy in the prevention of recurrences in unipolar and bipolar affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:1096–1104Google Scholar

5. Gelenberg AJ, Kane JM, Keller MB, Lavori P, Rosenbaum JF, Cole K, Lavelle J: Comparison of standard and low serum levels of lithium for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1489–1493Google Scholar

6. Reynolds CF III, Frank E, Perel JM, Miller MD, Cornes C, Rifai AH, Pollock BG, Mazumdar S, George CJ, Houck PR, Kupfer DJ: Treatment of consecutive episodes of major depression in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1740–1743Google Scholar

7. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kakuma T, Feder M, Einhorn A, Rosendahl E: Recovery in geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:305–312Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Meyers BS, Gabriele MS, Kakuma T, Ippolito L, Alexopoulos G: Anxiety and depression as predictors of recurrence in geriatric depression: a preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996; 4:252–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Frank E, Frank N, Cornes C, Imber SD, Miller MD, Morris SM, Reynolds CF: Interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of late-life depression, in New Applications of Interpersonal Psychotherapy. Edited by Klerman GL, Weissman MM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 167–198Google Scholar

11. Foglia JP, Stiller RL, Perel JM: The measurement of plasma nortriptyline and its isomeric 10-OH metabolites (abstract). Clin Chem 1987; 33:1024Google Scholar

12. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL: The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1980Google Scholar

14. Fleiss JL: Assessing significance in a fourfold table, in Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1981, pp 19–32Google Scholar

15. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Elkin I, Parloff MB, Hadley SW, Autry JH: NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: background and research plan. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:305–316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Åsberg M, Cronholm B, Sjoqvist F: Correlation of subjective side effects with plasma concentrations of nortriptyline. BMJ 1970; 137:18–21Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Reynolds CF III, Frank E, Perel JM, Imber SD, Cornes C, Miller MD, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Dew MA, Stack JA, Pollock BG, Kupfer DJ: Nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression: a randomized, controlled trial in patients older than 59. JAMA 1999; 281:39–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar