Spectrum of Activity of Lamotrigine in Treatment-Refractory Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: New mood stabilizers are needed that possess efficacy for all phases of bipolar disorder. This study was designed to provide preliminary evidence for the safety and efficacy of a new anticonvulsant, lamotrigine, in adult patients with bipolar disorder who had been inadequately responsive to or intolerant of prior pharmacotherapy. METHOD: A 48-week, open-label, prospective trial was conducted in 75 patients with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder. Lamotrigine was used as adjunctive therapy (N=60) or monotherapy (N=15) in patients presenting in depressed, hypomanic, manic, or mixed states. RESULTS: Of the 40 depressed patients included in the efficacy analysis, 48% exhibited a marked response and 20% a moderate response as measured by reductions in 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores. Of the 31 with a hypomanic, manic, or mixed state, 81% displayed a marked response and 3% a moderate response on the Mania Rating Scale. From baseline to endpoint, the depressed patients exhibited a 42% decrease in Hamilton depression scale scores, and the patients presenting with hypomania, mania, or a mixed state exhibited a 74% decrease in Mania Rating Scale scores. The most common drug-related adverse events were dizziness, tremor, somnolence, headache, nausea, and rash. Rash was the most common adverse event resulting in drug discontinuation (9% of patients); one patient developed a serious rash and required hospitalization. CONCLUSIONS: These open-label data provide preliminary evidence that lamotrigine may be an effective treatment option for patients with refractory bipolar disorder; however, potential benefits must be weighed against potential side effects, including rash.

The objective in the psychopharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder is the maintenance of euthymia through the prevention of cycling. Many patients require complex combinations of mood stabilizers with various psychotropics (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines) for optimal stabilization. At present, a broad-spectrum medication that is effective in all phases of the illness and that can be used in monotherapy is not available. Lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine possess moderate to marked antimanic properties; data suggest that valproate is more effective than lithium in mixed states (1). However, all three agents are typically less effective in the treatment of depression (1). This is an important clinical problem, since there is increased morbidity and mortality associated with the depressed and mixed phases of bipolar disorder (2–4). The use of marketed antidepressants puts bipolar patients at increased risk for drug-induced hypomania/mania and rapid cycling (5). New mood stabilizers are needed that possess comparable efficacy in the treatment of all phases of the illness, including mania, depression, and mixed states. A related need in the current pharmacologic treatment of patients with bipolar disorder is the development of an antidepressant suitable for use in rapid cycling that carries little or no increased risk of drug-induced mania and cycle acceleration.

Lamotrigine is an anticonvulsant drug of the phenyltriazine class that has been shown to be effective as adjunctive therapy and as monotherapy for partial seizures (6–10). Early observations regarding this drug’s putative psychotropic properties in patients with epilepsy (11), together with more recent anecdotal reports of its efficacy in bipolar disorder (12–17), including amelioration of rapid cycling and mixed states, provided the rationale for this prospective study. The objective of this preliminary study was to evaluate the spectrum of efficacy of lamotrigine as add-on therapy or monotherapy in patients with bipolar disorder who were inadequately responsive to or intolerant of pharmacotherapy.

METHOD

This multicenter study (Glaxo Wellcome protocol number 105-601) included three sites in the United States, one site in the United Kingdom, and one in Denmark. Seventy-five patients meeting the DSM-IV criteria for the depressed (N=41), hypomanic (N=6), manic (N=14), mixed (N=11), not otherwise specified (N=2), and unspecified (N=1) phases of bipolar disorder were enrolled in a prospective, 24-week open-label trial of lamotrigine followed by a second 24-week extension. Sixty-two (83%) of the patients had bipolar type I disorder, 11 (15%) had type II, and in two (3%) the disorder was not otherwise specified. Eighty-three percent had had past episodes requiring hospitalization, and the mean age at onset of illness was 24 years (SD=11). The patients were otherwise healthy men (N=30) and women (N=45), and their mean age at enrollment in the study was 44 years (SD=11, range=23–70). Four patients (5%) had current episode durations of less than 1 week, 19 (25%) 1–4 weeks, 12 (16%) 4–8 weeks, and 40 (53%) more than 8 weeks. Forty-one (55%) of the 75 patients met the DSM-IV criteria for rapid cycling.

To be included in the study, patients had to be inadequately responsive to or intolerant of prior pharmacotherapy as determined by the investigator. Patients with a history of epilepsy, clinically significant medical illness, a history of prior treatment with lamotrigine, active suicidality, or a history of alcohol or substance dependence within the past year were excluded. Lamotrigine was administered as an adjunct to existing medications for bipolar disorder (N=60) or as monotherapy (N=15). Changes in concomitant medications and doses during the first 24 weeks of the study were allowed only if carbamazepine or valproate levels deviated more than 50% from baseline, lithium levels required adjustment, or the patient’s condition deteriorated. Lorazepam, chloral hydrate, and oxazepam were used as needed (add-on or monotherapy) for control of insomnia and irritability. During the second 24 weeks of the study, concomitant psychiatric medications including antidepressants could be added or discontinued as clinically indicated. After a complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained, and after the first 24 weeks, written informed consent was again required for participation in the second 24 weeks of the trial.

On the basis of the presence of concomitant anticonvulsant enzyme inducers such as carbamazepine or enzyme inhibitors such as valproate, three lamotrigine dosing schedules, including both once-daily and twice-daily regimens, were used in order to provide similar lamotrigine plasma concentrations and reduce the risk of rash across the three dosing groups. The protocol stipulated that the rate of titration specified in these dosing schedules could not be exceeded. For patients receiving monotherapy or drugs other than valproate or carbamazepine, the lamotrigine dose was escalated as follows: weeks 1–2, 25 mg/day; weeks 3–4, 50 mg/day; and then increases of ≤50 mg/week up to a maximum daily dose of 500 mg. For patients taking concomitant valproate, the lamotrigine dose was escalated as follows: weeks 1–2, 25 mg every other day; weeks 3–4, 25 mg/day; and then increases of ≤25 mg every 2 weeks up to a maximum daily dose of 200 mg. For patients taking carbamazepine, the lamotrigine dose was escalated as follows: weeks 1–2, 50 mg/day; weeks 3–4, 100 mg/day; and then increases of ≤100 mg/week up to a maximum daily dose of 700 mg.

The 31-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, the Mania Rating Scale from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Change Version (18), the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) improvement and severity scales, and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (19) were administered at weeks 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 32, 40, and 48.

Reports of adverse events were elicited at each visit by a standard verbal probe. The investigator assessed intensity, seriousness, and possible causality (whether there was a reasonable possibility of a relationship between the event and the study medication).

Statistical analyses consisted of descriptive statistics and paired t tests for baseline (week 0) measures compared with the last observation carried forward. A responder analysis was also performed. Marked improvement was defined as a 50% or greater decrease in score from baseline to endpoint on the Mania Rating Scale or on the total score on the first 17 items of the Hamilton depression scale, and moderate improvement was defined as a 26%–49% decrease in these scores. Four patients were not included in the efficacy analyses. Three were excluded because they presented in unspecified phases of the illness; two of these patients received add-on lamotrigine, and one received lamotrigine monotherapy. One depressed patient was excluded because she experienced vomiting, which led to immediate drug discontinuation; she did not return after the screening visit for postbaseline efficacy measures. All patients were included in the safety analyses in which adverse events were summarized.

RESULTS

Eighty-four percent of the patients had been previously treated with lithium, 51% with carbamazepine, 49% with valproate, 76% with benzodiazepines, 92% with antidepressants, 67% with antipsychotics, 29% with ECT, and 17% with thyroxine. During the trial, 39 patients received concomitant antipsychotics, 29 received concomitant antidepressants, 26 received lithium (at study entry, the mean dose was 1013 mg/day, and the mean plasma concentration was 0.79 meq/liter), 22 received valproate (at study entry, the mean dose was 1517 mg/day, and the mean plasma concentration was 92 µg/ml), and 11 received carbamazepine (at study entry, the mean dose was 514 mg/day, and the mean plasma concentration 7 was µg/ml). The total average exposure to lamotrigine when administered in combination with other medications was 217 days; as monotherapy, 205 days; with carbamazepine, 278 days; and with valproate, 223 days. Thirty-eight (51%) of the patients dropped out of the study, including eight of the 15 monotherapy patients. The reasons for study discontinuation included adverse events in 14 patients (19%), lack of efficacy in 11 (15%), withdrawal of consent by five patients (7%), loss to follow-up of five (7%), and protocol violations in three cases (4%). One of the protocol violations involved the use of adjunctive clonazepam instead of lorazepam for the treatment of insomnia and agitation during the study. Four (5%) of the patients elected to discontinue participation after completing the original 24-week protocol.

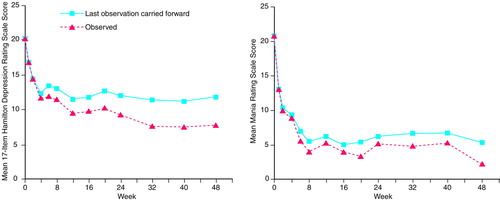

Forty-one (55%) of the 75 patients presented with depressive symptoms. One presented with an episode duration of less than 1 week, eight presented with durations of 1–4 weeks, six with 4–8 weeks, and 26 with more than 8 weeks. The efficacy results are shown in Table 1. The mean 17-item Hamilton depression scale score of the depressed patients decreased from a baseline of 20.3 to a last-observation-carried-forward value of 11.8. Figure 1, left side, shows the mean 17-item Hamilton depression scale results plotted over 48 weeks, which reveal statistically significant improvement after 7 days. Similar findings were observed for mean 31-item Hamilton depression scale scores (p<0.001). Of the patients presenting with depressive symptoms, 68% responded; 48% exhibited marked improvement and 20% moderate improvement. At the end of the trial, the mean CGI improvement score for the depressed patients was 3.0 (SD=1.5), with 15% very much improved, 30% much improved, 25% minimally improved, 13% showing no change, 8% minimally worse, and 10% much worse. In the subgroup of depressed patients who received lamotrigine monotherapy (N=8), four patients exhibited a marked response, one had a moderate response, and three had no response or a deterioration in their condition. There was a significant positive correlation between mean baseline Hamilton depression scale score and the last observed Hamilton depression scale value carried forward for patients who presented as depressed (Pearson correlation coefficient=0.36, N=40, p=0.02).

Thirty-one (41%) of the 75 patients presented as having a hypomanic, manic, or mixed state. Three patients presented with episode durations of less than 1 week, 11 presented with durations of 1–4 weeks, five with 4–8 weeks, and 12 with more than 8 weeks. These data were not available for two patients. Table 2 shows the efficacy results for this group. The mean Mania Rating Scale score decreased from a baseline of 20.9 to a last-observation-carried-forward value of 5.4. Figure 1, right side, shows the Mania Rating Scale results plotted over 48 weeks, which reveal statistically significant improvement after 7 days. Of the patients with a hypomanic, manic, or mixed presentation, 84% responded; 81% exhibited a marked response and 3% a moderate response. At the end of the trial, the mean CGI improvement score was 2.5 (SD=1.6), with 33% of the patients very much improved, 27% much improved, 13% minimally improved, 13% showing no change, 7% minimally worse, and 7% much worse. Of the subgroup of hypomanic, manic, and mixed bipolar patients who received lamotrigine monotherapy (N=6), five exhibited a marked response, none a moderate response, and one no response. In this subgroup of patients, there was a significant positive correlation between the mean baseline Mania Rating Scale score and the mean last observed Mania Rating Scale value carried forward (Pearson correlation coefficient=0.40, N=31, p=0.03).

The prevalence of drug-related adverse events occurring in 10% or more of the patients was 29% for dizziness, 23% for tremor, 21% for somnolence, 19% for headache, 15% for nausea, 15% for rash, and 13% for insomnia. Adverse events leading to drug discontinuation included rash in seven patients, nausea in one, somnolence in one, and tremor in one. Twenty-two patients (29%) experienced serious adverse events, the majority of which were associated with the course of the illness (i.e., psychiatric symptoms). Approximately 11% of the adverse events were rated by investigators as severe at their maximum intensity; the remaining adverse events were rated as mild to moderate.

Rash attributable to the study drug was observed in 11 patients (15%); seven (9%) were withdrawn from the study, and seven, including six of the seven who withdrew, experienced the rash within 8 weeks of the start of treatment. During the first 8 weeks, the prevalence of drug-related rash was 8% for the 12 patients taking concomitant valproate and 10% for the 63 patients taking lamotrigine without any concomitant valproate. Four of the 11 patients had a mild rash, five moderate, and two severe. One patient developed a serious rash while receiving lamotrigine monotherapy and required hospitalization during which steroid treatment was necessary.

Four patients experienced exacerbation of mania that necessitated hospitalization after lamotrigine exposures of 14, 15, 24, and 190 days; one of these patients was withdrawn from the study. Four patients experienced switches into mania that necessitated hospitalization after lamotrigine exposures of 14, 35, 66, and 90 days; two were withdrawn from the study. One of the four patients who experienced exacerbation of mania and two of the four patients who experienced switches into mania were rapid cycling at the initiation of lamotrigine treatment.

DISCUSSION

Evidence from this preliminary open-label trial suggests that lamotrigine was efficacious in reducing affective symptoms in patients presenting with treatment-refractory depressed, hypomanic, manic, and mixed phases of bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. The magnitude of observed improvement was large, with depressive symptoms exhibiting a 42% decrease from baseline Hamilton depression scale scores and hypomanic/manic/mixed symptoms exhibiting a 74% decrease from baseline Mania Rating Scale scores. Moderate to marked responses were seen in 68% of the patients who presented with depression and 84% of the patients who presented with hypomanic, manic, or mixed states. Increasing degrees of baseline depression and severity of mania appeared to predict lack of response to treatment. Lamotrigine seemed to be equally effective as adjunctive therapy or monotherapy. The effects in patients with bipolar disorder that is not treatment-refractory and the comparability of lamotrigine with other mood stabilizers cannot be determined from this study.

The most important finding concerning safety was the occurrence of rash. Rash was considered to be lamotrigine-related in 15% of the patients. Seven patients were withdrawn because of rash, mainly early in treatment, and one patient was hospitalized. In open-label and placebo-controlled clinical trials involving 3,501 epilepsy patients (20), rash was observed in 10% of lamotrigine-treated patients and 5% of placebo-treated patients; rash led to drug discontinuation for 3.8% and hospitalization for 0.3% of the lamotrigine patients. In general, the risk of rash is increased by coadministration of valproic acid or by exceeding the recommended initial dose or rate of dose escalation of lamotrigine (20). Controlled clinical trials of lamotrigine in patients with bipolar disorder are needed to properly evaluate the risk of rash and weigh the benefits and risks of lamotrigine treatment in the context of each patient’s severity of illness and responsiveness to other drugs.

This study had several important limitations. The principal limitations were the open-label design and the absence of a comparison group. Another limitation was the absence of a standardized definition of inadequate response to prior treatment, although the patients had long histories of psychiatric illness averaging 20 years; 83% had bipolar type I, and 83% had required prior hospitalization. Also, the study did not require life charting or count episodes between visits; therefore, the drug’s spectrum of prophylactic efficacy is not clear from the results. Another limitation associated with the study design was that psychiatric medications could be altered during the study. Also, its dose-finding feature allowed the investigator to titrate the dose according to response. As a result, it is likely that partial responders and nonresponders continued to have their doses escalated, skewing the mean last daily dose upward. At present, the minimum therapeutic dose of lamotrigine is unclear; however, significant reductions in Hamilton depression scale and Mania Rating Scale scores were observed at the starting dose after 7 days of lamotrigine treatment. Alternatively, the clinical improvement observed during the first week could have been due to a nonspecific placebo-type effect.

In an attempt to replicate and extend these preliminary open-label findings, a series of multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies is taking place to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and dose-response relationships of lamotrigine in the various phases of the illness, including acute and maintenance treatment designs for both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder.

Presented in part at the 149th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 4–9, 1996, and the annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, San Juan, Puerto Rico, Dec. 9–13, 1996. Received March 3, 1998; revisions received Oct. 15 and Dec. 23, 1998; accepted Feb. 2, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati; Royal London Hospital, London College of Medicine; Vordingborg Hospital, Vordingborg, Denmark; and Glaxo Wellcome, Inc., Research Triangle Park, N.C. Address reprint requests to Dr. Calabrese, Mood Disorders Program, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, 11400 Euclid Ave., Suite 200, Cleveland, OH 44106. Supported by a grant from Glaxo Wellcome, Inc.

|

|

FIGURE 1. Mean Scores on the 17-Item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale of Bipolar Patients With Depression and Mean Scores on the Mania Rating Scale of Bipolar Patients in Hypomanic, Manic, or Mixed States During Lamotrigine Treatmenta

aFor the depressed bipolar patients, at week 48 the mean Hamilton depression scale score was significantly different from the baseline score in the last-observation-carried-forward analysis (N=40) (t=–5.87, df=39, p=0.0001) and in the analysis of observed values at each time point (t=–8.57, df=19, p=0.0001). For the patients with hypomania, mania, or mixed states, at week 48 the mean Mania Rating Scale score was significantly different from the baseline score in the last-observation-carried-forward analysis (N=31) (t=–9.12, df=30, p=0.0001) and in the analysis of observed values at each time point (t=–7.66, df=13, p=0.0001).

1. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Woyshville MJ: Lithium and anticonvulsants in bipolar disorder, in Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. Edited by Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ. New York, Raven Press, pp 1099–1111Google Scholar

2. Calabrese JR, Woyshville MJ, Kimmel SE, Rapport DJ: Mixed states and bipolar rapid cycling and their treatment with valproate. Psychiatr Annals 1993; 23:70–78Crossref, Google Scholar

3. McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Faedda GL, Swann AC: Clinical and research implications of the diagnosis of mixed mania or hypomania. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1633–1644Google Scholar

4. Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, West SA: Suicidality among patients with mixed and manic bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:674–676Link, Google Scholar

5. Bauer MS, Calabrese J, Dunner DL, Post R, Whybrow PC, Gyulai L, Tay LK, Younkin SR, Bynum D, Lavori P, Price RA: Multisite data reanalysis of the validity of rapid cycling as a course modifier for bipolar disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:506–515Link, Google Scholar

6. Schachter SC, Leppik E, Matsuo F, Messenheimer JA, Faught E, Moore EL, Risner ME: Lamotrigine: a six month, placebo-controlled, safety and tolerance study. J Epilepsy 1995; 8:201–209Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Messenheimer J, Ramsay R, Willmore L, Leroy R, Zielinski J, Mattson R, Pellock J, Valakas A, Woulbe G, Risner M: Lamotrigine therapy for partial seizures: a multicenter placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over trial. Epilepsia 1994; 35:113–121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Chang G, Vasquez B, Gilliam F, Sackellares JC, Burns P, Risner M, Rudd GD: Lamictal (lamotrigine) monotherapy is an effective treatment for partial seizures (abstract). Neurology 1997; 48:A335Google Scholar

9. Brodie M, Richens A, Yuen A, UK Lamotrigine/Carbamazepine Monotherapy Trial Group: Double-blind comparison of lamotrigine and carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy. Lancet 1995; 345:476–479Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Matsuo F, Bergen D, Faught E, Messenheimer JA, Dren AT, Rudd GD, Lineberry CG, US Lamotrigine Protocol 05 Clinical Trial Group: Placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of lamotrigine in patients with partial seizures. Neurology 1993; 43:2284–2291Google Scholar

11. Smith D, Chadwick D, Baker G, Davis G, Dewey M: Seizure severity and the quality of life. Epilepsia 1993; 34(suppl 5):S31–S35Google Scholar

12. Weisler R, Risner ME, Ascher J, Houser T: Use of lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar disorder, in 1994 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994, p 216Google Scholar

13. Calabrese JR, Fatemi SH, Woyshville MJ: Antidepressant effects of lamotrigine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1236Medline, Google Scholar

14. Walden J, Hesslinger B, van Calker D, Berger M: Addition of lamotrigine to valproate may enhance efficacy in the treatment of bipolar affective disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry 1996; 29:193–195Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Sporn J, Sachs G: The anticonvulsant lamotrigine in treatment-resistant manic-depressive illness. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:185–189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kusumakar V, Yatham LN: Lamotrigine in treatment refractory bipolar depression. Psychiatry Res 1997; 72:145–148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Mandoki M: Lamotrigine/valproate in treatment resistant bipolar disorder in children and adolescents (abstract). Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41(suppl):93SGoogle Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Change Version, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

19. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Physicians’ Desk Reference, 51st ed. Montvale, NJ, Medical Economics Co, 1997, pp 1105–1110Google Scholar