Comparative Effectiveness of Fluphenazine Decanoate Injections Every 2 Weeks Versus Every 6 Weeks

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Dose reduction strategies for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia are designed to maintain the benefits of antipsychotic drug therapy while reducing risks. Previous strategies with decanoate preparations have been based on the use of lower doses per injection to achieve dose reduction; these strategies have achieved dose reduction but have resulted in some increase in symptoms. The authors tested a new dose reduction approach: increasing the interval between injections during intramuscular decanoate antipsychotic treatment. METHOD: Fifty outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were randomly assigned to receive 25 mg of fluphenazine decanoate intramuscularly either every 2 weeks or every 6 weeks for 54 weeks in a double-blind design. RESULTS: The two dose regimens did not differ significantly in relapse, symptom, or side effect measures. The every-6-weeks regimen was associated with a significant reduction in total antipsychotic exposure. CONCLUSIONS: The use of injections every 6 weeks instead of every 2 weeks may increase compliance and improve patients’ comfort as well as decrease cumulative antipsychotic exposure, without increasing relapse rates or symptoms. (Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:412–418)

Conventional antipsychotic drug treatment alleviates symptoms and reduces relapse rates in patients with schizophrenia, but side effects are common. Some are bothersome (e.g., dry mouth), some are dysphoric (e.g., akathisia), some are disfiguring (e.g., tardive dyskinesia), and some are frightening and painful (e.g., dystonia), while others are dangerous (e.g., neuroleptic malignant syndrome) or mimic aspects of the disease (e.g., sedation/apathy and akinesia/diminished emotional expression). These adverse drug effects interfere with function, reduce the quality of the patient’s life, cause poor compliance, and compromise treatment effectiveness.

Long-acting injectable medications were introduced to address the compliance problem. Injectable medication is especially successful for patients who forget or do not bother with oral administration. It is less successful for patients who decline antipsychotic medication because of unpleasant side effects. One motivation for the development of dose reduction strategies has been to reduce side effects and thereby increase compliance.

It has been demonstrated that dose reduction during maintenance therapy is feasible (1–6). Cumulative medication reduction has been achieved either by lowering the dose while maintaining a standard frequency of administration (7–10) or by targeting standard dose administration to early signs of exacerbation (10–16). Most course-of-illness measures reflect few differences between standard and reduced dose strategies. Patients tend to have more problems with psychotic symptoms when the dose is reduced, usually in the context of exacerbations that are managed on an outpatient basis. Some measures, such as negative symptoms, dyskinetic movements, social functioning, and patient and family satisfaction with treatment, have slightly favored the low-dose strategies (3). These results present the clinician with somewhat different profiles of risks and benefits and make it possible to tailor treatment to the individual patient.

Fluphenazine decanoate dose reduction studies have reduced medication doses to 10%–25% of standard doses of fluphenazine decanoate while maintaining the usual biweekly intramuscular injection schedule. An alternative strategy is to increase the interval between administrations of the standard dose. Several studies have suggested that many patients do not require biweekly fluphenazine decanoate to maintain remission. In double-blind withdrawal studies, the majority of patients who were randomly assigned to placebo remained clinically stable 6 weeks following their last injection (17, 18). Patients continued to have detectable levels of fluphenazine up to 6 months after their last injection (18) and significant D2 receptor occupancy for at least 4 months (19).

There may be several advantages associated with reducing the frequency of intramuscular injections. Depot is superior to oral antipsychotic medication for relapse prevention (20) but is underused in the United States, where about 10% of patients receive long-acting injections (21). Less frequent administration would please the clinician, the patient, and third-party payers, and it might improve compliance. This method should also lead to lower cumulative doses and thereby reduce rates of adverse effects, including tardive dyskinesia. To examine the feasibility of less frequent administration, we conducted a double-blind, stratified-assignment clinical trial comparing 54 weeks of standard fluphenazine decanoate treatment (25 mg every 2 weeks) with experimental dose reduction (25 mg every 6 weeks).

METHOD

Subjects

Patients meeting DSM-III-R criteria or Research Diagnostic Criteria for either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were recruited from a research clinic and an urban community mental health center. Patients were diagnosed by using a best-estimate diagnostic approach, which used all available information from direct assessment, family informants, and past medical records. Patients with a history of severe head trauma, current drug abuse, mental retardation, or a medical condition that could interfere with the evaluation or treatment of schizophrenia were excluded from the study. All subjects gave written informed consent before admission into the study according to consent procedures approved by the university institutional review board.

Study Design

Each patient received treatment from a team that included a primary therapist/case worker and a psychiatrist/pharmacotherapist. Patient visits were scheduled either weekly or biweekly, with additional visits if needed. At the beginning of the stabilization phase, patients received 25 mg of intramuscular fluphenazine decanoate every 2 weeks. The minimum duration of the stabilization phase was 6 weeks, or three fluphenazine decanoate injections, and patients were required to meet criteria for clinical stability before entry into the double-blind phase. Clinical stability was defined as three consecutive identical Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores. Patients were then randomly assigned to receive either 25 mg of fluphenazine decanoate every 2 weeks (N=25) or 25 mg of fluphenazine decanoate every 6 weeks (N=25). Random assignment to each group was stratified on the basis of 1) the sum of the scores for the work, social relations, and hospitalization items from the Prognostic Scale (22) and 2) history of relapse during the previous 6 months.

All patients received an injection every 2 weeks; one group received fluphenazine in each injection, and the other received two placebo injections between each active fluphenazine injection. The duration of the double-blind phase was 54 weeks; 27 active injections were planned for the every-2-weeks group, and nine active injections were planned for the every-6-weeks group.

The clinical condition of patients was evaluated at each visit. If a worsening in clinical status was noted by the patient’s therapist, a Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), CGI, and clinical assessment of the patient’s sleep pattern were conducted to determine whether the criteria for exacerbation (detailed later in this paper) were met. If a patient met exacerbation criteria, then open-labeled oral fluphenazine was added to the patient’s treatment regimen. The patient was maintained on a regimen of oral fluphenazine until the patient’s therapist and physician clinically judged that the patient had regained clinical stability.

Clinical assessments

The following assessments were used: CGI, Quality of Life Scale (23), Level of Functioning Scale (22), BPRS, and the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center Involuntary Movement Scale (24). All assessments were collected at baseline. The BPRS and CGI were conducted at least monthly throughout the study, and the Quality of Life Scale, Level of Functioning Scale, and Maryland Psychiatric Research Center Involuntary Movement Scale were conducted at the beginning, middle, and end of the study. Rater training on each instrument was conducted in the National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Research Center at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, and interrater reliability (intraclass correlations) for clinician and research raters ranged from ICC=0.78 to ICC=0.91 for these instruments.

Exacerbation

A clinical exacerbation was considered treatment failure for the purposes of analysis if both of the following criteria were met:

1. The patient’s therapist and physician observed a substantial worsening and judged that intervention was clinically indicated.

2. One or more of the following: a) an increase of 3 points on one or more of the following items on the most recent BPRS: conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, unusual thought content, suspiciousness, anxiety, hostility, or somatic concern; b) a new complaint of marked insomnia or a family-reported change in sleep pattern; c) an increase of 3 or more on the CGI, or an increase to 7.

Statistical Analyses

The primary research hypothesis was that there would be similar efficacy between treatment every 2 weeks and treatment every 6 weeks. The primary outcome measure for this hypothesis was the time to first treatment failure. The number of treatment failures and number of hospitalizations further describe this outcome. Secondary hypotheses concerned reduced cumulative dose and reduced side effects in the patients given the drug every 6 weeks. The primary outcome measures for these hypotheses were total (oral and intramuscular) antipsychotic dose and side effect measures.

The Lee-Desu test, derived from a proportional hazards survival model, was used to compare survival to exacerbation between the two treatment groups (25). Data for all study participants were included in the survival analysis. Chi-square analyses were used to compare treatment failure and hospitalization rates between treatment groups for patients who completed the study. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate treatment effects among patients who completed the study for duration of exacerbation, for hospitalization, and for cumulative antipsychotic dose and total fluphenazine hydrochloride dose. Repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to evaluate the effect of treatment every 2 weeks versus every 6 weeks on symptom and function measures; the two treatment groups were the between-subjects factors. The two time periods (6 months and 12 months) made up the repeated measure factor. The covariates were baseline ratings of patients who completed the study. ANCOVA was also used to evaluate treatment effects (2 weeks versus 6 weeks was the between-subjects factor) for baseline-adjusted 12-month ratings of patients who completed the study.

Additional analyses were performed to evaluate the comparability of the treatment groups and to assess whether those who completed the study were representative of the entire study group. Two-way ANOVAs, with treatment group membership and dropout versus completer status as between-subjects factors, were performed on measures of age, education, education of the head of household when the patient was 16, Prognostic Scale score, baseline BPRS ratings, and the number of days receiving fluphenazine decanoate during the baseline period. The possibility of sex differences between treatment groups was evaluated in a two-by-two chi-square analysis. One-way ANOVA and chi-square analysis were used to evaluate differences in demographic and clinical status at baseline between the research clinic and urban mental health center sites.

We considered a 20% difference between treatments in rate of treatment failure to be a clinically significant difference and calculated study power on that basis (26).

RESULTS

The study group consisted of 50 outpatients with schizophrenia (N=47) or schizoaffective disorder (N=3). There were no significant differences between the groups given fluphenazine decanoate every 2 weeks and those given the drug every 6 weeks in any of the demographic or clinical variables (table 1.). Overall, the patients’ prognosis was fair, as indicated by a mean score of 5.1 (SD=2.6) on the Prognostic Scale (27); this score falls between scores reflecting excellent (score=12) and poor (score=0) prognostic status. The mean duration of illness for the total study group—13.0 years (SD=6.6)—indicated a generally chronic course of illness.

Twenty-nine subjects were recruited from the research clinic and 21 from the urban community mental health center. Patients’ socioeconomic status and ages were comparable for the two sites. Site effects were evaluated in a proportional hazards model of survival until treatment failure. No site differences were observed in the survival curves (Lee-Desu statistic=0.86, df=1, p=0.35) or in treatment failure rates (χ2=0.28, df=1, p=0.60), and data from the two sites were combined for the primary analyses.

Of the 50 subjects who entered the study, 33 patients completed the 1-year study period and 17 ended their participation early. There were two administrative dropouts, 11 associated with symptom exacerbation, two due to side effects, and two due to noncompliance. All patients who dropped out of the study were followed up with routine clinical care. Completion rates were similar for the patients given the drug every 2 weeks (17 patients) and those give the drug every 6 weeks (16 patients) (χ2=0.09, df=1, p=0.76). Also, those who completed the study were comparable to dropouts on most demographic and baseline clinical measures (table 2.). All 50 patients were informative in the survival analysis up to the time of withdrawal, and the 11 patients who discontinued study participation because of symptom exacerbation are included in the time to first treatment failure.

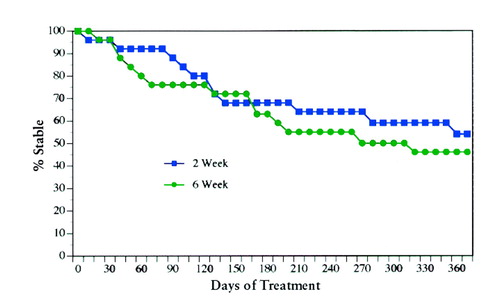

The numbers of patients who met treatment failure criteria were similar in the group given the drug every 2 weeks (N=11) and the group given the drug every 6 weeks (N=13) for all patients beginning treatment. Proportional hazards survival models of relapse rates were also similar for the two treatment conditions (Lee-Desu statistic=0.49; df=1, p=0.48) (figure 1). Two patients were hospitalized, both from group given the drug every 2 weeks. Relapse durations were comparable for the patients who completed the study in both groups (mean=11.0 days, SD=24.0, for every 2 weeks and mean=9.9 days, SD=18.2, for every 6 weeks) (F=0.02, df=1, 31, p=0.64).

The goal of cumulative fluphenazine dose reduction was met with the every-6-weeks strategy. The mean cumulative fluphenazine dose over the 1-year period was 725 mg (SD=176) for the every-2-weeks group and 439 mg (SD=503) for the every-6-weeks group (Kruskal-Wallis χ2=17.2, df=1, p<0.0001). The medication decrease was achieved through the use of less frequent injections. Mean cumulative injectable doses were 633 mg (SD=49) for the every-2-weeks group and 209 mg (SD=12) for the every-6-weeks group (F=1131.2, df=1, 31, p=0.0001). Mean cumulative oral fluphenazine doses were 91 (SD=160) for the every-2-weeks group and 230 (SD=502) for the every-6-weeks group (Kruskal-Wallis χ2=0.95, df=1, p=0.33). The mean daily oral fluphenazine hydrochloride dose for patients receiving oral medication was 8.1 mg (SD=4.0) for the every-2-weeks group and 7.1 mg (SD=2.2) for the every-6-weeks group (F=0.33, df=1, 11, p=0.58). The mean duration of oral supplementation was 12.0 days (SD=20.3) for the every-2-weeks group and 28.3 days (SD=56.8) for the every-6-weeks group (Kruskal Wallis χ2=0.67, df=1, p=0.41).

Both treatment groups had low levels of extrapyramidal and dyskinetic symptoms at baseline and throughout the study (table 3.). Maryland Psychiatric Research Center Involuntary Movement Scale ratings were available for 30 of 33 patients who completed the study. The 6-month and 1-year extrapyramidal symptom and dyskinesia scores, adjusted for baseline, were similar for the every-2-weeks and every-6-weeks groups and did not change significantly during the study. Psychosocial functioning and symptom outcomes (BPRS total and factor I) were comparable for the two treatment groups, reflecting mild to moderate impairment for the duration of the study (table 4.). Level of Functioning Scale, Quality of Life Scale, and BPRS ratings (total and all five factors) did not differ as a function of treatment condition, treatment duration, or their interaction. Statistical power to detect a 20% superiority for every-2-weeks fluphenazine decanoate was greater than 0.80 with alpha at 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Results were straightforward: there were no differences between the every-2-weeks and every-6-weeks fluphenazine decanoate regimens in treatment efficacy or effectiveness. The patients given the drug every 6 weeks achieved a significant decrease in cumulative antipsychotic dose without a symptomatic disadvantage. There were no significant differences in adverse drug effects or in functioning measures that, because of decreased antipsychotic exposure, might have favored the lower dose.

The limitations of our design should be borne in mind. First, results are most likely to generalize to relatively stable outpatients with a chronic form of illness. Second, differences between the two treatment regimens may have become apparent with a longer period of study. The relatively long time required for fluphenazine blood levels to achieve new equilibrium after reduction in fluphenazine decanoate dose shortened the observation period during which dose-related differences might have emerged. Marder et al. (9) reported more mild exacerbations with a low dose during year 2 of their study. We do not have year-2 data, but we did compare results in the second 6-month period with those in the first 6 months. Exacerbation rates were comparable across the two time periods (χ2=0.3, df=1, p=0.85). It is also possible that the patients who received the drug every 6 weeks might have improved more on measures of side effects and quality of life than those who received the drug every 2 weeks if the study period had been longer.

The number of patients studied was also a limiting factor, and a much larger study group would have been necessary to have sufficient statistical power to decide there was no difference between the every-2-weeks and every-6-weeks groups (to accept the null hypothesis). However, there were no trends in the data toward treatment group differences, and the study’s statistical power to detect a 20% superiority for every 2 weeks exceeded 0.80. Therefore, the major questions regarding inferences to be drawn from the present results are 1) whether they are replicable, 2) whether they would hold up over longer periods of time, and 3) to what populations these results generalize.

In contrast to more aggressive dose reduction approaches, there were no apparent disadvantages associated with less frequent injection intervals. Continuous low doses of targeted drugs (10%–25% of the standard dose) result in less medication exposure and more symptom exacerbations. In the present study, the patients given fluphenazine decanoate every 6 weeks achieved a 40% reduction in cumulative dose (oral plus injectable) without disadvantage in symptom course. Moreover, our failure to find a significant advantage in giving the drug every 2 weeks supports the proposition that standard practice often results in patients’ receiving more maintenance medication than required to prevent relapse.

If the every-6-weeks dose reduction method is associated with less difficulty than the more aggressive approaches, we think the difference is related to dose. From a pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic standpoint, there is no reason to hypothesize that the less frequent injection schedule is critical. Furthermore, giving the standard dose every 6 weeks was not superior to giving the standard dose every 2 weeks in symptom management in this study. Advantages, then, are associated with dose reduction and ease of application. Although the frequency of clinical visits is important, it probably does not account for the apparent advantage of the every-6-weeks dose reduction method over the more aggressive dose reduction studies because similar continuity of clinical care was provided in most of those studies.

In reporting this study, we have not addressed clinical therapeutics beyond the pharmacological aspects of administering long-acting injectable medication. Outpatients with schizophrenia usually require frequent clinic visits to maintain insight, to detect changes in psychopathology or in daily living circumstances, and to develop a clinical relationship from which to address issues ranging from stress and suicide to enhancing quality of life. Unfortunately, patients are sometimes given appointment schedules in relation to medication checks instead of the broader context of treatment. The reduced readmission rates now being reported with new-generation drugs may be the result (at least in part) of more intensive clinical care that was initiated with the weekly blood monitoring required with clozapine. We emphasize that the feasibility of reducing the frequency of fluphenazine decanoate injections does not imply that patients can or should be seen less frequently. The extremely low rehospitalization rate observed in this study may be the result of a pattern of care that permits early detection of symptom exacerbation with quick clinical intervention, including temporary supplementation with oral medication. The pattern of care that provides clinic visits every 4–8 weeks without outreach does not provide the psychosocial treatment needed to reduce stress, enhance coping, or detect early signs of relapse. Emergency rooms, hospitals, and jails routinely deal with the consequence of delayed and ineffective intervention. The feasibility of less frequent injections provides no basis for de-emphasizing continuity of care.

A final comment concerns the applicability of these data in the light of the new generation of antipsychotic medications with their more benign motor side effect profiles. Antipsychotic dose reduction strategies have been introduced in an effort to reduce adverse effects, enhance compliance, and provide targeted drugs when patients refuse continuous medication, or when they are medication-free for other clinical or research purposes. The new-generation drugs share the advantage of causing fewer extrapyramidal symptoms and, perhaps, being less likely to cause tardive dyskinesia. To the extent that these drugs are successful in maintenance treatment, the role of conventional antipsychotics and dose reduction strategies will be diminished. Some of the new drugs appear not to have a linear relation between dose and extrapyramidal side effects in the therapeutic range (28, 29), and a low-dose strategy has been the basis of marketing for risperidone.

A dysphoric response to antipsychotic medication and poor compliance is not only a problem of extrapyramidal side effects, however. Data comparing low-dose decanoate fluphenazine or haloperidol with the new medications will be important because, to date, the advantages for the new generation of antipsychotics (clozapine excepted in treatment-refractory patients) are primarily seen when compared with higher doses of conventional oral antipsychotic drugs. For example, the therapeutic advantage reported at one (of five) dose levels of risperidone for generic negative symptoms was observed when 20 mg/day of haloperidol was the comparison condition (30, 31). This advantage was not observed in a larger study in which 10 mg/day of haloperidol was used (32). Clinical and economic considerations require an increased emphasis on comparisons of optimal (in contrast to standard) conventional antipsychotic treatment with the new drugs. Such comparisons would provide the clinician with an expanded array of treatment options to offer the patient with schizophrenia.

Long-acting, injectable antipsychotic medication has substantial advantages for many patients and is underused. Fluphenazine and haloperidol are the only decanoate preparations approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The present study suggests a “user friendly” approach that may encourage physicians and patients to consider this dose reduction strategy as a therapeutic option.

Received April 6, 1998; revision received Sept. 14, 1998; accepted Sept. 21, 1998. From the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. Address reprint requests to Dr. Carpenter, Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, P.O. Box 21247, Baltimore, MD 21228; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-40279 and MH-35996.

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. Percentage of Schizophrenic Outpatients Who Remained Clinically Stable While Receiving 25 mg of Fluphenazine Decanoate Every 2 (Q 2) Weeks (N=25) or Every 6 (Q 6) Weeks (N=25)

1. Baldessarini RJ, Cohen BM, Teicher M: Pharmacologic treatment, in Schizophrenia: Treatment of Acute Psychotic Episodes. Edited by Levy ST, Ninan PT. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990, pp 61–118Google Scholar

2. Bollini P, Pampallona S, Orza MJ, Adams ME, Chalmers TC: Antipsychotic drugs: is more worse? a meta-analysis of the published randomized control trials. Psychol Med 1994; 24:307–316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Buchanan RW, Carpenter WT: Targeted maintenance treatment in schizophrenia: issues and recommendations. CNS Drugs 1996; 4:240–245Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Dixon LB, Lehman AF, Levine J: Conventional antipsychotic medications for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:567–577Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kane JM: Schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:34–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kane JM, Marder SR: Psychopharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:287–302Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hogarty GE, McEvoy JP, Magnets M, Dauber AL, Barbone P, Casher R, Cooley SJ, Ulrich RF, Carter M, Madonia MJ, Environmental/Personal Indicators in the Course of Schizophrenia Research Group: Dose of fluphenazine, familial expressed emotion, and outcome in schizophrenia: results of a two-year controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:797–805Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kane JM, Rifkin A, Woerner M, Reardon G, Sarantakos S, Schiebel D, Ramon-Lorenzi J: Low-dose neuroleptic treatment of outpatient schizophrenics, I: preliminary results for relapse rates. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:893–896Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Marder SR, Van Putten T, Mintz J, Lebell M, McKenzie J, May PRA: Low- and conventional-dose maintenance therapy with fluphenazine decanoate: two-year outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:518–521Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schooler NR, Keith SJ, Severe JB, Matthews SM, Bellack AS, Glick ID, Hargreaves WA, Kane JM, Ninan PT, Frances A, Jacobs M, Lieberman JA, Mance R, Simpson GM, Woerner MG: Relapse and rehospitalization during maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:453–463Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Carpenter WT, Heinrichs DW: Early intervention, time-limited, targeted pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1983; 9:533–542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Carpenter WT Jr, Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE: A comparative trial of pharmacologic strategies in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1466–1470Link, Google Scholar

13. Carpenter WT Jr, Hanlon TE, Heinrichs DW, Summerfelt AT, Kirkpatrick B, Levine J, Buchanan RW: Continuous versus targeted medication in schizophrenic outpatients: outcome results. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1138–1148Link, Google Scholar

14. Herz MI, Glazer WM, Mostert MA, Sheard MA, Szymanski HV, Hafez H, Mirza M, Vana J: Intermittent vs maintenance medication in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:333–339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Jolley AG, Hirsch SR, McRink A, Manchanda R: Trial of brief intermittent neuroleptic prophylaxis for selected schizophrenic outpatients: clinical outcome at one year. BMJ 1989; 298:985–990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pietzcker A, Gaebel W, Kopcke W, Linden M, M�ller P, M�ller-Spahn F, Tegeler J: Intermittent versus maintenance neuroleptic long-term treatment in schizophrenia—2-year results of a German multicenter study. J Psychiatr Res 1993; 27:321–339Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Shenoy RS, Sadler AG, Goldberg SC, Hamer RM, Ross B: Effects of a six-week drug holiday on symptom status, relapse, and tardive dyskinesia in chronic schizophrenics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1981; 1:141–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Wistedt B, Jorgensen A, Wiles D: A depot neuroleptic withdrawal study: plasma concentration of fluphenazine and fluphenthixol and relapse frequency. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982; 78:301–304Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Farde L, Nordstrom AL, Nyberg S, Halldin C, Sedvall G: D1-, D2-, and 5-HT2-receptor occupancy in clozapine-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(9, suppl B):67–69Google Scholar

20. Davis JM, Janicak PG, Singla A, Sharma RP: Maintenance antipsychotic medication, in Antipsychotic Drugs and Their Side-Effects. Edited by Barnes TRE. New York, Academic Press, 1993, pp 183–203Google Scholar

21. Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Phase II Workgroup: Primary Data Analysis. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research, Jan 22, 1997Google Scholar

22. Hawk AB, Carpenter WT, Strauss JS: Diagnostic criteria and five-year outcome in schizophrenia: a report from the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:343–356Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr: The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull 1984; 10:388–398Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Cassady SL, Thaker GK, Summerfelt A, Tamminga CA: The Maryland Psychiatric Research Center Scale and the characteristics of involuntary movements. Psychiatry Res 1997; 70:21–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lee ET, Desu MM: A computer program for comparing K samples with right-censored data. Comput Programs Biomed 1972; 2:315–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Blackwelder WC, Chang MA: Sample size graphs for “proving the hypothesis.” Control Clin Trials 1984; 5:97–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia, II: relationships between predictor and outcome variables: a report from the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 31:37–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Arvanitis LA, Miller BG: Multiple fixed doses of “Seroquel” (quetiapine) in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a comparison with haloperidol and placebo. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:233–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Tran PV, Hamilton SH, Kuntz AJ, Potvin JH, Andersen SW, Beasley C Jr, Tollefson GD: Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:407–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Chouinard G, Jones B, Remington G, Bloom DJ, Addington D, MacEwan GW, Labelle A, Beauclair L, Arnott W: A Canadian placebo-controlled study of fixed doses of risperidone and haloperidol in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:25–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Marder SR, Meibach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:825–835Link, Google Scholar

32. M�ller-Spahn F: Risperidone in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients: an international double-blind parallel-group study versus haloperidol (abstract). Clin Neuropharmacol 1992; 15:90A–91ACrossref, Medline, Google Scholar