Heritability of Anxiety Sensitivity: A Twin Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In attempting to explain the familial predisposition to panic disorder, most studies have focused on the heritability of physiologic characteristics (e.g., CO2 sensitivity). A heretofore unexplored possibility is that a psychological characteristic that predisposes to panic—anxiety sensitivity—might be inherited. In this study, the authors examined the heritability of anxiety sensitivity through use of a twin group. METHOD: Scores on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index were examined in a group of 179 monozygotic and 158 dizygotic twin pairs. Biometrical model fitting was conducted through use of standard statistical methods. RESULTS: Broad heritability estimate of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index as a unifactorial construct was 45%. Additive genetic effects and unique environmental effects emerged as the primary influences on anxiety sensitivity. There was no evidence of genetic discontinuity between normal and extreme scores on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index. CONCLUSIONS: This study suggests that one psychological risk factor for the development of panic disorder—anxiety sensitivity—may have a heritable component. As such, anxiety sensitivity should be considered in future research on the heritability of panic disorder.

Anxiety sensitivity is the fear of anxiety-related sensations. It is thought to arise from beliefs that these sensations have harmful consequences (1–4). For example, an individual may fear that the sensation of palpitations indicates a serious, life-threatening condition, such as a heart attack. According to expectancy theory, such an individual may become anxious whenever this symptom is experienced and may tend to avoid activities or places that are believed to bring it on. Anxiety sensitivity theory proposes that some individuals are more prone than others to respond to anxiety symptoms in this fashion. In other words, the higher an individual’s level of anxiety sensitivity, the more that individual is likely to experience anxiety symptoms as alarming, dangerous, and threatening.

There is considerable empirical support for the role of anxiety sensitivity in panic disorder (for reviews see references 4 and 5). Anxiety sensitivity, as assessed by the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (6), is higher in people with panic disorder than in healthy comparison subjects and in patients with another anxiety disorder, social phobia (7, 8). In normal volunteers, anxiety sensitivity predicts anxious responding to a variety of panic-provoking paradigms such as hyperventilation and CO2 inhalation (9–11). However, anxiety sensitivity does not seem to predict consistently response to all agents that induce panic, cholecystokinin tetrapeptide being a case in point (12; see reference 13 for review).

Anxiety sensitivity has also been found to be a risk factor for the development of panic disorder. In a prospective study of young adults under stress (i.e., military basic trainees), anxiety sensitivity was found to predict the onset of panic attacks (as well as generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms) over a 5-week period (14). The latter finding, which has since been replicated (cited in reference 15), confirms that high anxiety sensitivity at one time point is associated with the development of panic disorder (and perhaps other anxiety or depressive disorders) at a later time point.

Panic disorder runs in families (16–20). Moreover, twin studies clearly demonstrate that the disorder is heritable (21–24). The latter finding has generally been interpreted to mean that patients with panic disorder inherit a physiologic or biological risk factor for panic. Enhanced sensitivity to 35% CO2 among family members of patients with panic disorder has emerged as a promising candidate in this regard (25, 26). Surprisingly, though, little attention has been paid to the possibility that the transmission of a psychological construct such as anxiety sensitivity might explain the heritable nature of panic disorder. This is despite the fact that Reiss and McNally originally posited that genetic factors might influence anxiety sensitivity (3) and despite a growing awareness that other complex attitudes and behaviors can have a heritable basis. The purpose of the present study was to 1) estimate the magnitude of genetic and environmental influences on anxiety sensitivity, and 2) determine whether the magnitude of any genetic influence on anxiety sensitivity changes when only cases of extreme anxiety sensitivity (such as would be seen in panic disorder) are examined. Since most authorities agree that anxiety sensitivity is multifactorial (27, 28), we examined the heritability of anxiety sensitivity as a unifactorial and multifactorial construct.

METHOD

Subjects

The subjects were 337 volunteer urban general population twin pairs recruited from the area of Vancouver, B.C., Canada. The study group included 179 monozygotic twin pairs (mean age=32.13 years, SD=12.11, range=16–79) and 158 dizygotic twin pairs (mean age=31.34, SD=12.04, range=16–66). The monozygotic twin pairs consisted of 45 brother pairs (mean age=31.82, SD=12.94, range=16–71) and 134 sister pairs (mean age=32.23, SD=11.87, range=16–79). The dizygotic twin pairs consisted of 28 brother pairs (mean age=32.50, SD=13.84, range=18–66), 94 sister pairs (mean age=31.48, SD=12.86, range=16–66), and 36 brother-sister pairs (mean age=30.06, SD=13.13, range=18–66).

Twin pairs were recruited through newspaper advertisements, print and radio media stories, and through twin club registries to participate in a study of personality. Zygosity was determined through use of a highly accurate questionnaire (29, 30) and examination of recent color photographs. All subjects gave written informed consent to participate in this study, which was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of British Columbia.

Measures and Procedure

Twin pairs completed a packet of questionnaires at home. They were instructed to complete the questionnaires independently of one another in a nondistracting setting. Included in the packet was the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (6), a 16-item self-report questionnaire. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, where respondents indicate the extent to which each item corresponds to their beliefs about the consequences of their anxiety symptoms. Items are rated from 0 to 4 (0=not at all and 4=very much). Total Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores are obtained by summing the responses to each of the 16 items. The Anxiety Sensitivity Index has been shown to have excellent psychometric properties both in clinical and nonclinical samples (6).

Statistical Analysis

Factor analysis of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index

Whereas some studies support a single-factor structure for the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (31), others have concluded that it is multifactorial (28). Given the controversy over the factor structure of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index, we conducted an obliquely rotated principal components analysis of the scale’s items, which is consistent with extraction and rotational methods used elsewhere (5). We used one randomly selected member of each twin pair for the analyses. A clear three-factor solution emerged (eigenvalues >1.0) with loadings similar to that reported by Stewart et al. (27). The factors were named physical concerns, psychological concerns, and social concerns, and they accounted for 34.3%, 9.9%, and 8.4% of the total variance, respectively. Factor intercorrelations ranged from 0.12 to 0.42 (table 1). Factor scores were computed for each factor for all subjects.

Heritability estimates

A critical assumption of the twin method is that the environments of monozygotic and dizygotic twins are not systematically different from each other, which could influence the degree of twin similarity. No significant differences were detected between monozygotic and dizygotic twins for the number of separations greater than 1 month (t=–1.73, df=333, p=0.08), for number of serious illnesses (t=0.99, df=334, p=0.32), and for two true/false items assessing the similarity of environments for same-sex twins (“We attend the same school” [χ2=3.75, df=1, p=0.05] and “Our parents treat us pretty much the same” [χ2=3.25, df=1, p=0.07]).

Significant monozygotic to dizygotic differences were detected on three true/false items (“We spend most of our time together,” “We have the same friends,” and “We tend to dress alike” [χ2=18.38–32.39, df=1, p<0.05]), accounting for a small proportion of the variance across Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores (adjusted r2=3.1%–6.4%). Heritability estimates can also be biased by age and gender effects (32). In the present group these variables accounted for a negligible proportion of the variance in any of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores (adjusted r2=0.002–0.01).

Biometrical model fitting

Model fitting began with the computation of Pearson r values between co-twins separately for monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs; the computer program PRELIS 2 (33) was used. In general, larger monozygotic than dizygotic correlations indicate that genetic influences are present because the greater monozygotic similarity is attributed to the twofold greater genetic similarity of monozygotic than dizygotic twins. Biometrical models were fit to the covariance matrices by the method of maximum likelihood, through use of the computer program LISREL 8 (34).

The first series of models estimated the proportion of variance attributable to additive genetic factors (a); nonadditive genetic variance due to genetic epistasis, primarily due to genetic dominance (d); shared environmental factors (c); and nonshared environmental factors (e). Additive genetic influences represent the extent to which genotypes “breed true” from parent to offspring. Genetic dominance represents genetic effects attributable to the interaction of alleles at the same locus, which results in a character that is not exactly intermediate in expression, as would be expected between pure-breeding (i.e., homozygous) individuals. Genetic dominance effects were estimated only for those items for which these effects were indicated by a monozygotic correlation that was more than twice the magnitude of the dizygotic correlation (35). The shared component of the environment distinguishes the general environment of one family from that of another and influences all children within a family to the same degree (e.g., socioeconomic status). Nonshared environmental factors (35, 36) include events that have differential effects on individual family members (e.g., illness, pre- and postnatal traumas, and differential parental treatment). These nonshared, within-family differences extend to the influence of extrafamilial networks, such as differences in peer groups, teachers, or relatives that may cause siblings to differ. It should be noted that nonshared environmental influences are not measured directly but represent the residual variance after the influences of a, d, and c have been removed. Thus, this component of variance also contains measurement error.

The first model fit to the data was the “full model” that specified a, c, and e (or a, d, and e, if appropriate) influences. The full model was systematically modified to test the significance of a, d, c, and e by fitting a series of “reduced” models. These models systematically removed the effects of 1) additive genetic variance (ce model), 2) shared environmental variance or nonadditive genetic effects (ae model), and 3) both additive and nonadditive genetic and shared environmental variance (e only model). The relative fit of each reduced model was assessed by testing the difference in chi-square values between the full and reduced models. The critical value of chi-square to test the chi-square difference is determined by the difference in the number of degrees of freedom between the full and reduced models under consideration. The reduced model was rejected whenever the chi-square difference exceeded the critical value of chi-square. Model fit was also assessed in conjunction with two other criteria: the principle of parsimony and Akaike’s information criterion (37) (chi-square minus two degrees of freedom). As such, the best-fitting model is the one that does not significantly increase chi-square, accounts for the variance with the fewest number of parameters, and yields the smallest value of Akaike’s information criterion. The parameter estimates obtained from the best-fitting model are squared to yield the familiar proportions (percent) of the variance attributable to each genetic and environmental influence: h2 (additive genetic factors), d2 (when applicable) (nonadditive genetic factors), c2 (shared environmental factors), and e2 (nonshared environmental factors).

Heritability of High Anxiety Sensitivity Index Scores

A common assumption of heritability studies of psychiatric disorder is that the same etiological mechanisms operate in the normal and extreme (characteristic of psychiatric disorder) ranges of functioning (38). This assumption can be addressed by comparing the magnitude of genetic influences on extreme scores (defined by a clinically significant threshold on a quantitative measure) to the magnitude of genetic influences on the entire range of scores (39). Estimation of the heritability of extreme range scores or “group heritability” is possible by using a quantitative method known as the DF analysis (40, 41). On a single measure, this method uses data from a single sample in which an extreme group has been identified to estimate group heritability and to estimate the heritability of scores throughout the entire response distribution (symbolized as h2). In short, the assumption that scores from the normal and extreme ranges are influenced by common genetic factors is not supported if normal range scores have a significant heritable basis and extreme range scores do not (h2g<h2), and vice versa. However, a finding that the magnitude of genetic influences on extreme and normal range scores is similar (h2g=h2) implicates common genetic factors, although it is possible that qualitatively different etiological factors influence normal and extreme range scores to the same degree.

A multiple regression procedure (40, 41) estimates group heritability from a sample of monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs in which the score from one member of a pair exceeds a threshold value. The method uses the extent to which the scores from the unaffected monozygotic to dizygotic members of each twin pair differ. Specifically, no genetic influence on the extreme scores is indicated when, despite the twofold greater genetic similarity of monozygotic to dizygotic twins, the mean scores of the unaffected monozygotic to dizygotic co-twins are equal. Genetic influences are suggested when the mean scores of the unaffected monozygotic co-twins exceed the scores of the dizygotic co-twins. A t test of the difference between the unaffected monozygotic and dizygotic co-twin means yields a significance test of genetic influences on the extreme scores. For the Anxiety Sensitivity Index, a score of 25 or greater is typically associated with a clinical condition such as panic disorder (7, 31). A series of thresholds (representing scores of 26, 27, 28, and 29) were tested to examine at what level of extremity differential heritable effects (if any) may be observed. For pairs in which both members’ scores exceeded the threshold value, one twin was randomly assigned to the co-twin group and the other was assigned to the proband group to control for ascertainment bias.

RESULTS

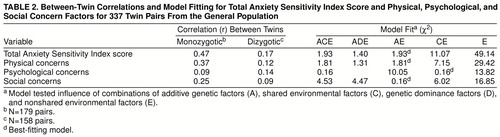

Twin correlations and model-fitting statistics are presented in table 2. A model specifying additive genetic and nonshared environmental effects (AE model) provided the most satisfactory fit to the total Anxiety Sensitivity Index score and the physical and social concern factors. A model specifying shared and nonshared environmental effects (CE model) could account for all of the variance of psychological concerns. Table 3 presents the parameter estimates, standard errors, and the heritability estimates. Additive genetic factors accounted for 45%, 35%, and 22% of the total variance on the total Anxiety Sensitivity Index score, physical concerns scores, and social concerns scores, respectively. Shared environmental influences accounted for 11% of the total variance on psychological concerns. Nonshared environmental influences (and error) accounted for the greatest proportion of the variance on all scales (range=55% to 89%).

Table 4 provides the results of the DF analysis. Group heritability, or the heritable basis of the total Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores above the threshold of 25 to 28, ranged from 45% to 63%. The 95% confidence interval around the heritability estimate of the total Anxiety Sensitivity Index score for the total group is 0.33–0.59. The group heritability estimates generally fall within this confidence interval, suggesting that there is no genetic discontinuity between normal and extreme scores on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the heritability of anxiety sensitivity. We found that anxiety sensitivity has a strong heritable component, accounting for nearly half of the variance in total anxiety sensitivity scores. Results of the DF analysis showed that the magnitude of genetic effects across the whole range versus extreme range Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores fell within the same general parameters. These results support the idea that high scores on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (characteristic of panic disorder) and scores in the subclinical range share the same common genetic factors. We use the word “support” because it is possible that qualitatively different genetic factors influence extreme and normal range scores to the same degree.

Whereas it has generally been hypothesized that the heritable nature of panic disorder reflects the genetic transmission of a physiologic risk factor (e.g., hypersensitivity to CO2) (25, 26), this may be too narrow a formulation. In view of our findings, serious consideration should be given to the possibility that an attitudinal or cognitive risk factor (i.e., anxiety sensitivity) is being genetically transmitted. This should not be seen as an unexpected or novel hypothesis (3). As noted by Kendler (42), considerable evidence now points to the heritability of many complex psychological traits that may themselves serve as risk factors for psychiatric disorders. Certainly, personality traits have a large heritable component (43); hence, it is not surprising that anxiety sensitivity is also heritable. Thus, our findings raise the question of whether anxiety sensitivity is inherited independently from “neuroticism,” a question that we hope to address in future studies. Given the empirical support for heritability of a nonspecific neurotic factor in the anxiety disorders (44, 45), this must be seriously considered.

Our study has several limitations. Among these are a limited group size and few male twin pairs. Our interpretation of the data is also limited by the relatively restricted range of anxiety sensitivity scores encountered in this group of twins from the general population. We demonstrated that the upper range of anxiety sensitivity scores in our study group (i.e., high 20s) is not inherited differently from lower anxiety sensitivity scores; however, we cannot extrapolate with certainty to state that this will necessarily apply to the much higher anxiety sensitivity scores (i.e., 30 and above) seen in some patients with panic disorder. Thus, although we believe that our findings have relevance to the understanding of the heritability of disorders characterized by pathological levels of anxiety sensitivity (i.e., panic and perhaps other anxiety and depressive disorders) (4), this will require further study.

With these limitations in mind, our findings lead us to tentatively conclude that perhaps what is inherited in panic disorder is a tendency to view anxiety symptoms as frightening. It is expected that anxiety sensitivity, like other cognitive tendencies, will eventually be localized within specific neural networks (46). In order to make further advances in this regard, we would propose that future studies evaluate anxiety sensitivity and other risk factors within this broader context. For example, heritability studies of panic at the level of “disorder” might simultaneously examine anxiety sensitivity heritability at the level of “trait”; and functional neuroimaging studies of anxiety disorders might use neuropsychologically relevant tasks to activate neural structures (e.g., components of the limbic system) that could underlie anxiety sensitivity (47).

When the heritability of the three factors of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index are examined separately, there is some evidence for differential contributions of additive genetic and environmental influences. This must be considered a very tentative finding, given that there are differences among the factors in the number of items with salient loadings (i.e., the psychological and social concerns factors might be less reliable), which may lead to spurious findings in this regard. We found that shared environmental influences accounted for a substantial proportion (11%) of variance in the psychological concerns factor, suggesting that important aspects of this component are influenced by family environment. If this finding is confirmed, then the implication is that interventions directed toward the family milieu might lessen the development of anxiety sensitivity and, hence, might prevent the onset of some forms of psychopathology. Other investigators have similarly hypothesized that specific genetic factors or specific social learning experiences might influence specific factors of anxiety sensitivity (48), leading us to believe that this is an area ripe for further study.

Total Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores and scores on two of the three factors, most notably the physical concerns factor, were best modeled by using a combination of additive genetic and unique environmental influences. Environmental factors account for a large proportion of the variance in Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores, leading us to speculate about the nature of the experiences that may increase anxiety sensitivity and, hence, the risk for panic disorder. The literature suggests that several types of events deserve consideration in this regard. Childhood sexual or physical abuse, a known risk factor for the development of panic disorder (49), could produce feelings of loss of bodily autonomy and concerns related to physiologic hyperarousal. Suffocation experiences (50) and other adverse respiratory experiences in childhood, such as asthma (51, 52), might sensitize an individual to fear sensations associated with breathlessness. Learning to “catastrophize” about the occurrence of bodily symptoms in general might also lead to higher than normal levels of anxiety sensitivity (53). Thus, although our findings highlight the heritable nature of anxiety sensitivity, they also point to the need to identify experiential factors that influence anxiety sensitivity and to investigate how these factors interact with genetic factors to trigger panic attacks.

Received April 13, 1998;revision received Aug. 14, 1998; accepted Sept. 24, 1998. From the Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada. Address reprint requests to Dr. Stein, Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry (0985), University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0985; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by a fellowship from the Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation to Dr. Jang, by grant 181(91-2) from the British Columbia Health Research Foundation, and by grant MA9424 from the Medical Research Council of Canada to Dr. Livesley. The authors thank Steven Taylor, Ph.D., for his input and for his critique of an earlier draft of the manuscript.

|

|

|

|

1. Reiss S: Expectancy theory of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clin Psychol Rev 1991; 11:141–153Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ: Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency, and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther 1986; 24:1–8Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Reiss S, McNally RJ: Expectancy model of fear, in Theoretical Issues in Behavior Therapy. Edited by Reiss S, Bootzin RR. New York, Academic Press, 1985, pp 107–121Google Scholar

4. Taylor S: Anxiety sensitivity: theoretical perspectives and recent findings. Behav Res Ther 1995; 33:243–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Cox BJ: The nature and assessment of catastrophic thoughts in panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 1996; 34:363–374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Peterson RA, Reiss S: Anxiety Sensitivity Index Manual, 2nd ed. Worthington, Ohio, International Diagnostic Systems, 1992Google Scholar

7. Taylor S, Koch WJ, McNally RJ: How does anxiety sensitivity vary across the anxiety disorders? J Anxiety Disorders 1992; 6:249–259Google Scholar

8. Hazen AL, Walker JR, Stein MB: Comparison of anxiety sensitivity in panic disorder and social phobia. Anxiety 1994; 1:298–301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Rapee RM, Brown TA, Antony MM, Barlow DH: Response to hyperventilation and inhalation of 5.5% carbon dioxide-enriched air across the DSM-III-R anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:538–552Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Asmundson GJ, Norton GR, Wilson KG, Sandler LS: Subjective symptoms and cardiac reactivity to brief hyperventilation in individuals with high anxiety sensitivity. Behav Res Ther 1994; 32:237–241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. McNally RJ, Eke M: Anxiety sensitivity, suffocation fear, and breath-holding duration as predictors of response to carbon dioxide challenge. J Abnorm Psychol 1996; 105:146–149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Koszycki D, Cox BJ, Bradwejn J: Anxiety sensitivity and response to cholecystokinin tetrapeptide in healthy volunteers. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1881–1883Link, Google Scholar

13. Stein MB, Rapee RM: Anxiety sensitivity: is it all in the head? in Anxiety Sensitivity: Theory, Research and Treatment of the Fear of Anxiety. Edited by Taylor S. Mahway, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (in press)Google Scholar

14. Schmidt NB, Lerew DR, Jackson RJ: The role of anxiety sensitivity in the pathogenesis of panic: prospective evaluation of spontaneous panic attacks during acute stress. J Abnorm Psychol 1997; 106:355–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Schmidt NB: Prospective evaluations of anxiety sensitivity in Anxiety Sensitivity: Theory, Research and Treatment of the Fear of Anxiety. Edited by Taylor S. Mahway, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (in press)Google Scholar

16. Noyes RJ, Crowe RR, Harris EL, Hamra BJ, McChesney CM, Chaudhry DR: Relationship between panic disorder and agoraphobia: a family study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:227–232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Vieland VJ, Goodman DW, Chapman T, Fyer AJ: A new segregation analysis of panic disorder. Am J Med Genet 1996; 67:146–153Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Fyer AJ, Mannuzza S, Chapman TF, Martin LY, Klein DF: Specificity in familial aggregation of phobic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:564–573Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Goldstein RB, Weissman MM, Adams PB, Horwath E, Lish JD, Charney D, Woods SW, Sobin C, Wickramaratne PJ: Psychiatric disorders in relatives of probands with panic disorder and/or major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:383–394Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Goldstein RB, Wickramaratne P, Horwath E, Weissman MM: Familial aggregation and phenomenology of “early”-onset at or before age 20 years panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:271–278Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Torgersen S: Genetic factors in anxiety disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:1085–1089Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: Panic disorder in women: a population-based twin study. Psychol Med 1993; 20:581–590Google Scholar

23. Skre I, Onstad S, Torgersen S, Lygren S, Kringlen E: A twin study of DSM-III-R anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 88:85–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Perna G, Caldirola D, Arancio C, Bellodi L: Panic attacks: a twin study. Psychiatry Res 1997; 66:69–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Perna G, Cocchi S, Bertani A, Arancio C, Bellodi L: Sensitivity to 35% CO2 in healthy first-degree relatives of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:623–625Link, Google Scholar

26. Perna G, Bertani A, Caldirola D, Bellodi L: Family history of panic disorder and hypersensitivity to CO2 in patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1060–1064Link, Google Scholar

27. Stewart SH, Taylor S, Baker JM: Gender differences in dimensions of anxiety sensitivity. J Anxiety Disord 1997; 11:179–200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Cox BJ, Parker JDA, Swinson RP: Anxiety sensitivity: confirmatory evidence for a multidimensional construct. Behav Res Ther 1996; 34:591–598Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Nichols RC, Bilbro WC Jr: The diagnosis of twin zygosity. Acta Genet Med Gemellol 1966; 16:265–275Google Scholar

30. Kasriel J, Eaves L: The zygosity of twins: further evidence on the agreement between diagnosis by blood groups and written questionnaires. J Biosoc Sci 1976; 8:263–266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. McNally RJ: Automaticity and the anxiety disorders. Behav Res Ther 1995; 33:747–754Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. McGue M, Bouchard TJ Jr: Adjustment of twin data on the effects of age and sex. Behav Genet 1984; 14:325–343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. J�reskog K, S�rbom D: PRELIS 2: A Preprocessor for LISREL. Chicago, Scientific Software, 1993Google Scholar

34. J�reskog K, S�rbom D: LISREL 8: A Guide to Program and Applications. Chicago, Scientific Software, 1993Google Scholar

35. Plomin R, Chipuer HM, Loehlin JC: Behavior genetics and personality, in Handbook of Personality Theory and Research. Edited by Pervin LA. New York, Guilford Press, 1990, pp 225–243Google Scholar

36. Rowe DC, Plomin R: The importance of nonshared (E1) environmental influences in behavioral development. Dev Psychol 1981; 17:517–531Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Akaike H: Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrica 1987; 52:317–332Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Rutter M: Epidemiological approaches to developmental psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:486–495Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Rende R: Genes, environment, and addictive behavior: etiology of individual differences and extreme cases. Addiction 1993; 88:1183–1188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. DeFries JC, Fulker DW: Multiple regression analysis of twin data. Behav Genet 1985; 15:467–473Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. DeFries JC, Fulker DW: Multiple regression analysis of twin data: etiology of deviant scores versus individual differences. Acta Genet Med Gemellol 1988; 37:205–216Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 Kendler KS: Social support: a genetic-epidemiologic analysis. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1398–1404Link, Google Scholar

43. Jang KL, Livesley WJ, Vernon PA, Jackson DN: Heritability of personality disorder traits: a twin study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 94:438–444Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Mackinnon AJ, Henderson AS, Andrews G: Genetic and environmental determinants of the lability of trait neuroticism and the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Psychol Med 1990; 20:581–590Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Andrews G, Stewart G, Allen R, Henderson AS: The genetics of six neurotic disorders: a twin study. J Affect Disord 1990; 19:23–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. McNally RJ: Information-processing abnormalities in anxiety disorders: implications for cognitive neuroscience. Cognition & Emotion 1998; 12:479–495Crossref, Google Scholar

47. Stein MB, Uhde TW: The biology of anxiety disorders, in The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Psychopharmacology, 2nd ed. Edited by Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998, pp 609–628Google Scholar

48. Taylor S, Cox BJ: Anxiety sensitivity: multiple dimensions and hierarchic structure. Behav Res Ther 1998; 36:37–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Stein MB, Walker JR, Anderson G, Hazen AL, Ross CA, Eldridge G, Forde DR: Childhood physical and sexual abuse in patients with anxiety disorders and in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:275–277Link, Google Scholar

50. Bouwer C, Stein DJ: Association of panic disorder with a history of traumatic suffocation. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1566–1570Link, Google Scholar

51. Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Otto MW, Rosenbaum JF, Kradin RL: Panic anxiety, dyspnea, and respiratory disease: theoretical and clinical considerations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 154:6–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Carr RE, Lehrer PM, Rausch LL, Hochron SM: Anxiety sensitivity and panic attacks in an asthmatic population. Behav Res Ther 1994; 32:411–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Watt MC, Stewart SH, Cox BJ: A retrospective study of the learning history origins of anxiety sensitivity. Behav Res Ther 1998; 36:505–525Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar