Lithium Discontinuation and Subsequent Effectiveness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Several reports have raised concern that the discontinuation of lithium may result in treatment resistance following recurrence of affective disorder. This report explores this possibility. METHOD: The data derive from a large, naturalistic follow-up of patients with major depressive disorder or mania. Twenty-eight of the patients in the study were free of lithium and experiencing an episode of mania or schizoaffective mania diagnosed according to Research Diagnostic Criteria when they entered the study, recovered while taking lithium, later experienced a recurrence while not taking lithium, and then resumed lithium treatment. Survival analyses of time to recovery and, subsequently, time to recurrence, used continued lithium treatment as an additional censoring variable. RESULTS: Patients given lithium recovered no more quickly from their index episode than they did from their first prospectively observed episode. Moreover, lithium prophylaxis appeared no less effective after the first prospectively observed episode than after the index episode. CONCLUSIONS: These findings provide no evidence that lithium discontinuation results in treatment resistance when lithium is resumed. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:895–898)

Several authors (1–3) have described patients who appeared to develop resistance to lithium therapy after treatment was discontinued and then resumed. These reports have serious clinical implications in that they suggest that lithium discontinuation may have lasting adverse consequences beyond the simple risk of recurrence. The causal relationship between lithium discontinuation and a subsequent increase in morbidity, however, is far from clear in the cases described. Post et al. (1) described four patients, and Bauer (2) described one, selected from an undetermined number of individuals who had discontinued lithium. This selection from a possibly much larger number who had interrupted lithium therapy without apparent untoward effects raises the likelihood that chance variations in clinical course were incorrectly attributed to changes in treatment. Moreover, in three cases, the reports provided neither the episode frequency before lithium was started nor the time elapsed between lithium discontinuation and the onset of new episodes. Evidence is scant, therefore, that these three patients were, in fact, lithium responsive before discontinuation.

Maj et al. (3) described a consecutive series of patients who stopped taking lithium for reasons other than episode recurrence and who then resumed lithium after one or more new episodes of mania or major depressive disorder. Although all had been symptom-free for at least 2 years before discontinuation, 10 (18.5%) relapsed in the following year. This was seen as evidence that either lithium discontinuation per se, or the occurrence of additional episodes, had promoted lithium resistance. The study did not include comparison patients who had not discontinued lithium, and naturalistic studies have shown that relapse during lithium prophylaxis is common, even after sustained periods without episodes (4).

The recent study by Tondo et al. (5) is particularly noteworthy in the light of these caveats. Tondo et al. identified a relatively large number of patients attending an affective disorders clinic who had discontinued, and later resumed, lithium treatment. Analyses revealed no evidence that these patients then experienced more episodes each year, or a greater percent of time ill, after lithium was resumed than they had during the previous period of lithium treatment. Patients experienced significantly less morbidity in both treatment epochs than they did before lithium was first started.

Thus, reports suggesting that lithium discontinuation may produce lithium resistance coexist with at least one to the contrary. None of these has clearly separated acute and prophylactic lithium responses. The analyses reported here were designed to do so.

METHOD

The data were derived from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression—Clinical Studies, a long-term, prospective follow-up that began with proband recruitment between 1978 and 1981, inclusive. Patients entered the study as they sought treatment at any one of five academic centers: the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and the Brockton, Mass., VA Hospital, Rush Presbyterian at St. Luke's Medical Center in Chicago, the University of Iowa College of Medicine in Iowa City, the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University in New York, and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. All participants provided written, informed consent after the procedures and risks involved had been fully explained to them. Raters used medical records, informants, and direct patient interviews with the Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (6) to assign diagnoses according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (7). They then used the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (8) to conduct follow-up interviews semiannually for the first 5 follow-up years and annually thereafter.

Participation in the study did not influence treatment, but the type and doses of all psychoactive medications were systematically monitored throughout on a week-by-week basis (9). The reasons for changes in dose or type of medication were not formally monitored, however. Lithium levels obtained by the treating physicians were recorded during the first 5 years of follow-up. Raters likewise quantified symptom levels for each RDC syndrome for each week of follow-up. “Recovery” required 8 consecutive weeks with no symptoms or no more than one or two symptoms to no more than a mild degree. A recurrence of the RDC syndrome required the reappearance of symptoms sufficient to meet criteria at the definite level.

The current study includes the patients who entered the NIMH study experiencing a current episode of RDC mania or schizoaffective disorder, manic type, exclusive of schizoaffective disorders with the mainly schizophrenic subtype. With this exclusion, the RDC for mania and for schizoaffective disorder, manic type, overlap substantially with the DSM-IV criteria for manic disorder and include patients with mood-incongruent psychotic features. Inclusion criteria for the current study also specified 1) recovery from the episode that had been evident at intake; 2) the subsequent appearance of at least one new episode of mania or schizoaffective mania; 3) the absence of lithium or any other thymoleptic medication (carbamazepine, valproate, clonazepam, or clonidine) during the week preceding study intake and during the first week of the prospectively observed episode; and 4) the use of lithium without other thymoleptics before the end of both the index episode and the prospectively observed episode.

To estimate the effectiveness of lithium in shortening manic episodes, we adopted life-table methods (10, 11) to include lithium discontinuation as a censoring variable. Survival curves began with the first week of lithium treatment and modeled time to recovery from the episode of mania or schizoaffective mania. Patients remained in the survival analysis until they recovered or were censored, e.g., discontinued lithium or were lost to follow-up.

To assess prophylactic efficacy, we identified patients from the previous analyses who recovered while taking lithium and continued taking lithium after recovery. Survival analyses then began with the ninth week of recovery, the first week after the 8 necessary to define recovery. In contrast to the analyses of acute efficacy, the endpoint here was the recurrence of another major depressive, manic, or schizoaffective episode. Censoring variables were, as before, the discontinuation of lithium or loss to follow-up before a recurrence was observed.

In the absence of a statistical test for the comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival times within subjects, we used Wilcoxon signed rank tests and modified times to recovery and recurrence. These modified values did not incorporate censoring in an ongoing fashion as the Kaplan-Meier statistic does. Instead, they were simply the number of weeks to recovery or recurrence, to lithium discontinuation, or to loss to follow-up, whichever occurred first.

RESULTS

A total of 185 individuals were experiencing an episode of mania or schizoaffective mania when they entered the NIMH study and were followed for at least 6 months. Of these, 11 did not recover from the index episode, 65 did not have another episode, 63 were already taking lithium, carbamazepine, or valproate when they entered the study, and another 18 failed to meet one or more of the remaining criteria.

Twenty-eight patients satisfied the criteria for the current study. Eighteen (64.3%) were women and four (14.3%) met RDC for schizoaffective mania when they entered our study. These patients did not differ from excluded patients in age, sex, or diagnostic composition.

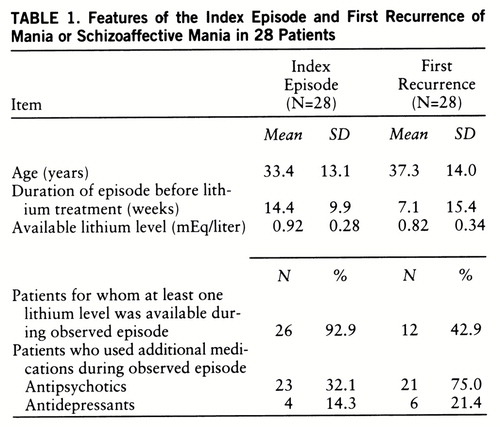

Symptoms of mania had been present somewhat longer before lithium treatment began in the index episode than in the first prospectively observed episode (table 1). Patients had been without lithium for a mean of 50.2 weeks (SD=72.7, range=2–303) before the first prospectively observed episode began. The two episodes did not differ in the likelihood that additional medications were used, nor did the mean values for available lithium levels differ significantly.

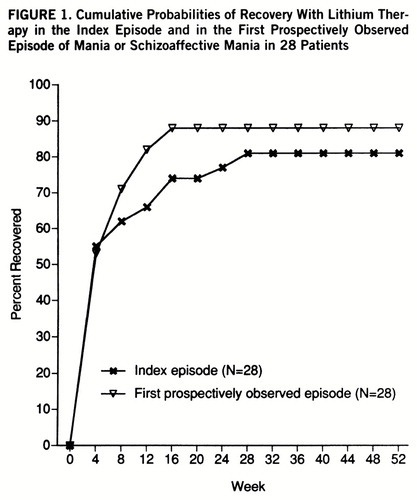

The first prospectively observed episode did not differ from the index episode in time to recovery (figure 1) (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p=0.153). The median times to recovery were 4.0 weeks for both manic episodes. The curves plateaued at 16 weeks, at which point 73.5% of the index episodes, and 88.2% of the first prospectively observed episodes, had ended (Kaplan-Meier estimates). Only one patient discontinued lithium before this point in the index episode. In the first prospectively observed episode, seven patients discontinued lithium prematurely. The modified times to recovery were greater for the index episode in 15 patients and for the first prospectively observed episode in 10 other patients; times to recovery were identical in three patients.

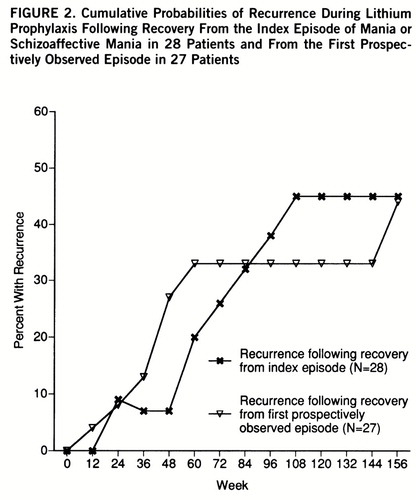

Twenty-eight of these individuals recovered from the index episode while taking lithium, and 27 recovered from the first prospectively observed episode while taking lithium. No clear differences emerged in risks for recurrence from these two episodes (figure 2). The projected recurrence rate at 2 years following recovery from the index episode was 45.0%; following recovery from the first prospectively observed episode it was 32.9% (Kaplan-Meier estimates). The difference in modified times to recurrence were not statistically significant (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p=0.57). Following recovery from the index episode, 13 patients discontinued lithium before a new episode developed; 11 discontinued lithium before recurrence following the first prospectively observed episode.

DISCUSSION

These within-subject comparisons yielded no significant differences or any clear trends to suggest that lithium discontinuation leads to reduced effectiveness. These data extend the conclusions of Tondo et al. (5) that neither acute nor prophylactic effectiveness appears to suffer after lithium interruption.

These results should be viewed in the context of the strengths and weaknesses of naturalistic studies. On the one hand, treatment decisions made by patients and their physicians in such studies are not regimented by protocol, and treatment factors such as dosing, target plasma levels, and types of lithium preparations are much more variable than they would be in a controlled trial. However, there seems little reason to suspect biases in treatment factors that would obscure a decrease in effectiveness in the episodes following lithium discontinuation.

On the other hand, a strength of a naturalistic study is its greater generalizability. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of controlled trials, the necessary willingness of subjects to abide by protocols and, often, to risk treatment with a placebo or with an agent they do not prefer, result in a highly select group quite unlike the majority of patients assigned treatment in the community.

Notably, neither our analyses nor the other reports concerning the long-term effects of lithium discontinuation directly quantify drug effects. This would require a controlled study that randomly assigned patients to lithium or placebo in both the first and second episodes. In the absence of placebo control, drug effects are embedded within, and inseparable from, spontaneous remissions or naturally episode-free subsequent courses. If such remissions were more common in subsequent episodes, and spontaneous recurrences were less common following them, then the natural history may have obscured a true decline in lithium efficacy. There is no obvious reason to expect such a change in natural history, however.

The number of patients described here was modest, and, if discontinuation-induced decreases in lithium effectiveness occurred in only a minority of the 28 patients, these analyses would have failed to detect an infrequent or small but clinically meaningful phenomenon. However, individual patients were as likely to show a decrease in time to recovery in later episodes as they were to show an increase.

Clinical decisions to continue or discontinue lithium, or any other thymoleptic, derive from estimates of cost-benefit ratios. These weigh side effects and the potential for toxicity against the increased risk for recurrence associated with discontinuation. These risks, in turn, can be estimated from the frequency and temporal proximity of past episodes, the usual severity of episodes, and the potential consequences of new episodes in an individual's current circumstances. These are complex judgments. At present, the balance of evidence does not indicate that the alleged loss of effectiveness consequent to lithium discontinuation should be considered an additional risk factor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression—Clinical Studies is conducted with the participation of the following investigators: M.B. Keller, M.D. (Chairperson, Providence, R.I.); W. Coryell, M.D. (Co-Chairperson, Iowa City); J.D. Maser, Ph.D. (Washington, D.C.); T.I. Mueller, M.D., M.T. Shea, Ph.D. (Providence, R.I.); J. Fawcett, M.D., W.A. Scheftner, M.D. (Chicago); W. Coryell, M.D., J. Haley (Iowa City); J. Endicott, Ph.D., A.C. Leon, Ph.D., J. Loth, M.S.W. (New York); J. Rice, Ph.D., T. Reich, M.D. (St. Louis). Other contributors include H.S. Akiskal, M.D., N.C. Andreasen, M.D., Ph.D., P.J. Clayton, M.D., J. Croughan, M.D., R.M.A. Hirschfeld, M.D., L. Judd, M.D., M.M. Katz, Ph.D., P.W. Lavori, Ph.D., D. Solomon, M.D., R.L. Spitzer, M.D., and M.A. Young, Ph.D. Deceased contributors are G.L. Klerman, M.D., E. Robins, M.D., R.W. Shapiro, M.D., and G. Winokur, M.D.

|

Received July 29, 1997; revision received Dec. 18, 1997; accepted Feb. 9, 1998. From the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression—Clinical Studies. Address reprint requests to Dr. Coryell, Psychiatry Research—MEB, University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa 52242-1000; [email protected] (e-mail). This manuscript has been reviewed by the Publication Committee of the Collaborative Depression Study and has its endorsement.

FIGURE 1. Cumulative Probabilities of Recovery With Lithium Therapy in the Index Episode and in the First Prospectively Observed Episode of Mania or Schizoaffective Mania in 28 Patients

FIGURE 2. Cumulative Probabilities of Recurrence During Lithium Prophylaxis Following Recovery From the Index Episode of Mania or Schizoaffective Mania in 28 Patients and From the First Prospectively Observed Episode in 27 Patients

1 Post RM, Leverich GS, Altshuler L, Mikalauskas K: Lithium-discontinuation-induced refractoriness: preliminary observations. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1727–1729Link, Google Scholar

2 Bauer M: Refractoriness induced by lithium discontinuation despite adequate serum lithium levels (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1522Link, Google Scholar

3 Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L: Nonresponse to reinstituted lithium prophylaxis in previously responsive bipolar patients: prevalence and predictors. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1810–1811Link, Google Scholar

4 Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, Mueller T, Lavori P, Keller M: The likelihood of recurrence in bipolar affective disorder: the importance of episode recency. J Affect Disord 1995; 33:201–206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Floris G, Rudas N: Effectiveness of restarting lithium treatment after its discontinuation in bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:548–550Link, Google Scholar

6 Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

8 Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, Mc~Donald-Scott P, Andreasen NC: The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:540–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Keller MB, Lavori PW, Klerman GL, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Coryell W, Fawcett J, Rice JP, Hirschfeld RM: Low levels and lack of predictors of somatotherapy and psychotherapy received by depressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:458–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Kaplan EL, Meier P: Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statistical Assoc 1958; 53:457–481Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL: The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1980, pp 12–15Google Scholar