Use of Health Services by Hospitalized Medically Ill Depressed Elderly Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined whether depression is associated with greater use of health services by elderly medical patients before and during hospitalization. METHOD: Depression and recent use of health services were assessed in 542 patients aged 60 or over who were consecutively admitted to university medical services. Depression was measured by using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and the depressive disorders section of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, which was administered by a psychiatrist. RESULTS: After age, sex, race, education, and severity of medical illness were controlled for, Hamilton depression score significantly predicted hospital days in the past year, hospital days and total inpatient days (hospital plus nursing home) in the past 3 months, and number of outpatient medical visits in the past 3 months. Depressed patients had more hospital days in the past year and had more hospital days, total inpatient days, and outpatient medical visits in the past 3 months than did nondepressed patients. Associations between depression and length of index hospital stay, home health visits, nursing home days, and number of prescription medications disappeared when severity of medical illness was controlled. Mental health visits were no more common among depressed than nondepressed patients. CONCLUSIONS: Depressed elderly medical inpatients used more hospital and outpatient medical services than nondepressed patients, but they did not receive more mental health services. Efforts by primary care physicians and third-party payers to identify and treat depression in this population are needed. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:871–877)

An increased prevalence of acute and chronic medical illness in later life results in a disproportionate use of general medical services by older adults. Persons over age 60 are hospitalized twice as often as younger adults, account for almost 50% of all short-stay hospital days, make more outpatient visits to physicians in a ratio of 3:2, and use twice as many prescription drugs (1). Despite decreasing hospitalization rates and length of stay due to managed care, the financial costs related to short-term medical hospitalization continue to dwarf all other medical expenditures (2).

When older persons are hospitalized with medical illness, they frequently experience emotional difficulties in coping with health problems and declining function. Studies by us and others (3, 4) indicate that depressive disorder is present in one-third to one-half of hospitalized medical patients over age 60. Depressive symptoms have often been present for many months before hospital admission, and they persist in the majority of patients for many months after hospital discharge (5, 6). Over 70% of these depressed patients are either untreated or treated inadequately (7, 8).

A number of studies have now demonstrated that heavy utilizers of health care services (all ages) often have comorbid medical and psychiatric illnesses. Katon et al. (9) reported that many distressed persons who had high levels of health care use had diagnoses of major depression, dysthymic disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder. Souetre et al. (10) reported that primary care patients with emotional disorder were more likely to be hospitalized and to have laboratory tests than patients without this problem and that they took more medications; costs of hospitalization accounted for over 53% of direct health care costs for these patients. Likewise, Simon et al. (11), studying a group of 327 primary care patients, found that those with anxiety or depressive disorders had markedly higher 6-month baseline costs (mean, $2,390) than patients with either subthreshold disorders ($1,098) or no disorder ($1,397); these cost differences persisted after adjustment for medical morbidity and were attributed to use of general medical services rather than mental health services.

Depression has also been associated with extended length of hospital stay (12, 13) and prolonged recovery from illness (14, 15) in medically ill older patients. We found that the hospital stays of depressed elderly veterans were twice as long as those of carefully matched nondepressed comparison subjects (13). Mossey et al. (14) and Parikh et al. (15) reported that recovery from hip fracture and recovery from stroke, respectively, were significantly prolonged in depressed older patients.

Given the aging U.S. population, the rising costs of health care, and the need to identify treatable psychiatric conditions that lead to excess utilization of expensive medical services, more information is needed about the association between depression and use of health services by medically ill older adults. The ideal time at which to study this association is when health service use is at its greatest—short-term hospitalization. El~derly medical inpatients have high rates of depression and have been shown to have high levels of use of the most costly form of medical care.

In the present study, we examined the use of outpatient and inpatient health services by depressed and nondepressed older medical patients before and during a short-stay medical hospitalization. We hypothesized that 1) use of health services before and during hospitalization would be positively correlated with severity of depressive symptoms, 2) patients with depressive disorders (major or minor depression) would utilize more outpatient and inpatient health services than nondepressed patients, and 3) these associations would remain significant after we controlled for severity of medical illness, demographic factors, and education.

METHOD

Study Group

The subjects were a consecutive series of patients aged 60 years or over who were admitted to the general medicine, cardiology, and neurology inpatient services of Duke University Medical Center. Roughly equal numbers were recruited from the three services. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: discharge before the third hospital day; discharge within 24 hours, precluding the psychiatric part of the evaluation; discharge or transfer to another service between days 3 and 7, before the baseline evaluation was completed; length of hospital stay exceeding 7 days; inability to obtain consent from physician; medical illness or cognitive impairment severe enough to preclude psychological testing; communication problem insurmountable by adaptive devices (hearing loss, aphasia, tracheostomy); transfer from a nursing home; treatment in an intensive care or critical care unit; and transfer from another service of the hospital.

Procedure

After fully explaining the procedures and obtaining written informed consent from the patient, a master's-degree-level research assistant administered the self-rated Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale) (16) and collected baseline demographic information. The research assistant also inquired about hospital use during the year before admission and other health service use during the 3 months immediately before admission. After this baseline evaluation, all patients were seen within 24 hours by a psychiatrist, who administered a structured psychiatric interview. With a subset of patients, the psychiatrist also performed a physical examination and reviewed the medical record.

The structured psychiatric evaluation included the depressive disorders section of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (17). The psychiatrist counted symptoms for the diagnosis of depression by using two approaches: 1) the “inclusive” approach, by which symptoms are counted in the diagnosis of depression regardless of presumed etiology; and 2) the “etiologic” approach, by which symptoms are counted in the diagnosis of depression only if “not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism)” (DSM-IV, p. 327). There are difficulties in applying the DSM-IV etiologic approach to sick elderly medical patients; symptoms of the patient's medical illnesses, even if not attributable to the physiologic effects of the illness, may produce all the symptoms of major depression (pain, for example). We have shown elsewhere that the inclusive approach is the most reliable and reproducible method for assessing symptoms of depression in this population (18) and is as accurate as the DSM-IV etiologic approach for predicting persistent depression after hospital discharge (5).

A diagnosis of major depression was made if within the past month the patient admitted to having 2 weeks or more of depressed mood or anhedonia, along with 2 weeks or more of four other DIS criterion symptoms. Minor depression was diagnosed if for 2 weeks or more within the past month the patient 1) experienced depressed mood or anhedonia and at least one other criterion symptom (but fewer than four symptoms) or 2) experienced three or more criterion symptoms in the absence of depressed mood or anhedonia. In addition, the psychiatrist rated symptom severity on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (19).

If patients scored 16 or higher on the CES-D Scale, scored 11 or higher on the Hamilton depression scale, and admitted to three or more criterion symptoms lasting 2 weeks or more during the past month, they were designated as depressed “cases.” If patients scored 10 or less on the CES-D Scale, scored 10 or less on the Hamilton depression scale, and admitted to two or fewer criterion symptoms, they were designated as nondepressed “control subjects.” The cases of depression included patients with either major or minor depression. Only patients fulfilling the criteria for either case or control status (63.1% of patients) were evaluated for use of health services during the hospital stay (e.g., medications on admission, medications at discharge, and length of hospital stay).

Data and Measures

The demographic information collected by the research assistant included age, race (black versus white), sex, education (at least some college versus other), insurance status (private versus staff), and admitting service (general medicine, cardiology, or neurology).

The information collected by the research assistant on use of health services included number of hospitalizations within the past year (before index admission at Duke), days hospitalized in the past year, days hospitalized within the past 3 months (before index admission), days spent in a nursing home in the past 3 months, visits to physicians (medical doctors), visits to mental health providers (psychiatrists, psychologists, or social workers), and visits by home health personnel (nurses, physical or occupational therapists, or home health aides). The length of hospital stay for the index admission and the numbers of prescription medications on admission and at discharge were determined by the psychiatrist who reviewed the complete medical record after hospital discharge.

After physically examining the patient and reviewing the medical record at the time of evaluation, the psychiatrist completed the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (20). This scale measures the severity of impairment on a 0–4-point scale for each of 12 organ systems and provides an overall score for severity of physical illness ranging from 0 to 48. It is a relatively objective measure of severity of medical problems.

Statistical Analyses

The associations between depressive symptoms (CES-D Scale or Hamilton depression scale score) and use of inpatient and outpatient health services were examined by using Pearson's correlations. The differences among the three groups of patients (major, minor, and no depression) on quantitative variables were determined by using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the differences among the three groups for qualitative variables were examined through chi-square analysis. If an ANOVA was significant, Bonferroni tests were conducted for post hoc comparisons of the three groups of patients. Multiple regression analyses were used to examine the association between health service use and each of the depressive symptom and depressive disorder variables, after we controlled for the covariates age, gender, race, education, and severity of medical illness. All of the analyses were carried out by using the statistical software SAS (21).

RESULTS

The research assistant completed baseline evaluations of 549 patients; of these, 542 patients (79.4% of the 683 eligible patients) were evaluated within 24 hours by the psychiatrist. The reasons for nonparticipation were failure to complete the psychiatric evaluation (N=7), refusal (N=26), prevention of interview by family, nurse, or house staff (N=74), and miscellaneous reasons (N=34). There was no significant difference between the participants (N=542) and nonparticipants (N=141) in terms of race, sex, insurance status, admitting service, or admitting medical diagnosis. The nonparticipants were older (mean age, 72.9 versus 70.2 years) and seen later in the hospital stay (mean, day 5.1 versus day 4.5) than were the participants. We compared the demographic characteristics of the 542 patients in our study group with those of the general population, on the basis of data collected from a random sample of 4,000 adults aged 65 or over living in central North Carolina (22). The percentages of women in our study group and in the general population were 51.8% and 62.6%, respectively; the percentages of black persons were 32.5% and 35.5%; and the percentages with at least 12 years of education were 42.6% and 29.0%.

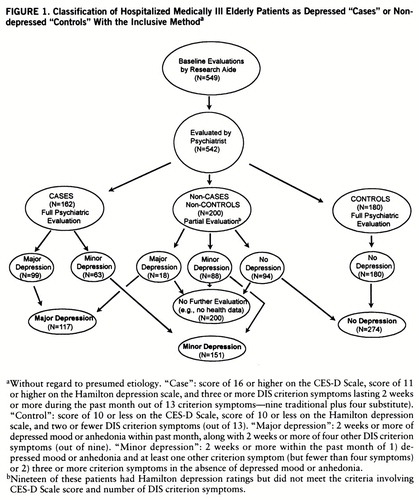

Figure 1 illustrates the patient classification. Of the 542 patients evaluated, 200 subjects fulfilled the criteria for neither case nor control status, and detailed psychiatric and health data were not collected on them. Nineteen of these patients had Hamilton depression ratings but did not qualify for case or control status because they did not meet the other criteria involving CES-D Scale score and number of DIS criterion symptoms. Of these 200, 18 fulfilled the DIS criteria for major depression, 88 met the DIS criteria for minor depression, and 94 were considered not depressed. Thus, when the inclusive approach was used, the final study group consisted of 117 patients with major depression, 151 with minor depression, and 274 with no depression. When the etiologic approach was used, 93 patients fulfilled the criteria for major depression, 84 met the criteria for minor depression, and 365 were considered not depressed.

Bivariate Correlational Analyses

Measures of both outpatient and inpatient health service use were significantly correlated with depressive symptoms, whether determined by the self-rated CES-D Scale or by the psychiatrist-rated Hamilton depression scale. The CES-D Scale score was related to days of hospitalization in the past year (r=0.15, N=542, p=0.0003), length of index hospital stay (r=0.10, N=340, p=0.06), and total inpatient days within the past 3 months (r=0.09, N=542, p=0.04). CES-D Scale score was also related to number of physician visits within the past 3 months (r=0.14, N=542, p=0.001) and number of prescription medications taken on admission (r=0.22, N=339, p<0.0001) and at discharge (r=0.26, N=339, p<0.0001). CES-D Scale score was unrelated to short-stay hospital days, nursing home days, home health visits, and visits to mental health providers in the past 3 months.

Likewise, the score on the Hamilton depression scale was significantly related to number of short-stay hospital days in the past year (r=0.32, N=361, p<0.0001), short-stay hospital days in the past 3 months (r=0.21, N=361, p<0.0001), length of index hospital stay (r=0.12, N=340, p=0.02), number of nursing home days in the past 3 months (r=0.13, N=361, p=0.02), and total inpatient hospital days in the past 3 months (r=0.24, N=361, p<0.0001). Hamilton depression score was also related to number of physician visits (r=0.24, N=361, p<0.0001), home health visits (r=0.15, N=361, p=0.006), and number of prescription medications taken on admission (r=0.29, N=339, p<0.0001) and at discharge (r=0.33, N=339, p<0.0001). Like the CES-D Scale score, the Hamilton depression score was unrelated to number of visits to mental health providers in the past 3 months.

Analyses of Variance

Results of ANOVAs of demographic, health, and health service use characteristics of the patients with major, minor, and no depressive disorder are presented in table 1. When a corrected p value of ≤0.05 was used, it was shown that patients with major depression were more likely to be women than were patients without depression. Patients with either major or minor depression were less likely than nondepressed patients to have private health insurance and at least some college education. The CES-D Scale and Hamilton scale scores differed significantly between the patients with major and minor depression and between the patients with major or minor depression and those without depression. As far as health characteristics were concerned, patients with major or minor depression were more likely than nondepressed patients to be admitted to the general medicine services (versus cardiology or neurology). Patients with major depression had more severe medical illness than those with minor depression, and those with major or minor depression had more severe illness than patients without depression.

With regard to health service use, patients with major but not minor depression had more hospital days in the past year than did patients without depression. Patients with major or minor depression, however, had more short-stay hospital days within the past 3 months than those without depression. Patients with major depression also spent significantly more days in nursing homes than did those with either minor depression or no depression. Total inpatient days (hospital and nursing home) and physician visits were greater for patients with major or minor depression than for those without depression. Home health visits were more frequent for patients with minor depression (but not major depression) than for those without depression. Finally, total numbers of medications on admission and at discharge were greater for patients with major or minor depression than for nondepressed patients. Thus, patients with major or minor depression tended to behave similarly in terms of health service use, and both used more health services than patients without depression.

Multiple Regression Analyses

Controlling for age, gender, race, education, and severity of illness, we conducted polynomial regressions to determine the association between health service use and depression variables along with second-order terms of age and severity of medical illness. The polynomial regressions did not show the significance of the second-order terms, and so all of the regressions were carried out without controls for the quadratic effects of these two variables.

Among the case and control subjects (N=341), multiple regression analyses continued to reveal associations between depression and service use after the covariates were controlled. Depressive symptoms (Hamilton depression score) continued to predict number of short-stay hospital days within the past year (t=3.5, df=1, p=0.0005; model R2=0.15, F=9.8, df=6,334) and numbers of short-stay hospital days (t=2.0, df=1, p=0.05; model R2=0.05, F=3.1, df=6,334), nursing home days (t=1.9, df=1, p=0.06; model R2=0.04, F=2.1, df=6,334), and total inpatient days within the past 3 months (t=2.8, df=1, p=0.005; model R2=0.10, F=6.0, df=6,334). Depressive symptoms also continued to predict number of outpatient physician visits (t=2.8, df=1, p=0.007; model R2=0.09, F=5.6, df=6,334). Associations between depressive symptoms and length of index hospital stay, home health visits, nursing home days, and prescription medications all disappeared once severity of medical illness was controlled.

The bivariate analyses described earlier revealed that the patients with major and minor depression were more similar to each other than to patients without depression. Therefore, for the multivariate regression models we combined the patients with major and minor depression (N=161) and compared them to the patients without depression (N=180). Patients thus categorized as depressed by the “inclusive” approach had more total inpatient days (hospital and nursing home) (t=2.2, df=1, p=0.03; model R2=0.09, F=5.4, df=6,334) and more medical outpatient visits (t=3.2, df=1, p=0.002; model R2=0.10, F=6.1, df=6,334) in the past 3 months than did nondepressed patients. There was also a tendency for depressed patients to have more short-stay hospital days in the past year (t=1.8, df=1, p=0.07; model R2=0.13, F=8.1, df=6,334) and in the past 3 months (t=1.9, df=1, p=0.06; model R2=0.05, F=3.0, df=6,334). There was no association, however, between depressive disorder and length of index hospital stay, nursing home days, home health visits, mental health visits, or prescription medications.

When the DSM-IV “etiologic” approach for diagnosing depression was used, the results were largely similar. The depressed patients had more short-stay hospital days in the past year (t=2.0, df=1, p=0.05; model R2=0.13, F=8.2, df=6,334) and more short-stay hospital days (t=2.1, df=1, p=0.04; model R2=0.05, F=3.1, df=6,334), more total inpatient days (t=2.5, df=1, p=0.01; model R2=0.09, F=5.7, df=6,334), and more physician visits (t=1.9, df=1, p=0.06; model R2=0.08, F=4.9, df=6,334) in the past 3 months.

No depressed patients were admitted to psychiatric hospitals during the 3 months before admission. Outpatient visits to mental health professionals (psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers) were also no more common among the depressed than nondepressed patients.

DISCUSSION

We examined associations between depression and use of health services by elderly medical inpatients before and during short-term hospitalization. Both depressive symptoms and depressive disorder significantly predicted greater use of outpatient and inpatient health services during the months before hospital admission, although they did not affect the length of the current hospital stay or medication use after severity of medical illness was controlled for.

In the year before the current hospital admission, patients with major depression spent twice as many days in the hospital as patients without major depression (mean, 12.1 days versus 5.7 days). These patients had been depressed an average of 5 months before the current admission, and fewer than one-third were receiving adequate doses of antidepressants (12). While it is not clear why the patients with depression in this study did not also have longer index hospital stays than patients without depression, it has been previously reported that depressive disorder doubles the length of hospital stays for elderly medical patients (13).

As noted earlier, short-term hospital care is the most expensive type of medical care and makes up the largest proportion of Medicare expenditures in the United States. An aging population, with increasing rates of chronic illness and disability, will inevitably require more short hospital stays for stabilization of acute exacerbations of illness (23). If nearly one-half of older hospitalized patients have comorbid depressive disorders when hospitalized (5) and these patients use significantly more short-term hospital services than do patients without depression, then depressive disorder may be a hidden cause of excess service use. Even small increases in service use due to untreated depression could substantially increase the cost of general medical care in this country.

We found not only that depressed patients used more short-term hospital inpatient services, but also that they saw their physicians more frequently as outpatients. In the 3 months before hospital admission, the patients with major depression saw physicians 70% more frequently than did nondepressed patients (mean, 5.6 versus 3.3 visits). This could not be explained by their age or severity of physical health conditions. Independent of these factors, depressed patients still used more outpatient medical services than did persons without depression. However, it is interesting that the depressed patients in this study—the majority of whom had been depressed for many months—had on the average only 0.2 visits per month to mental health professionals (about the same number as the nondepressed subjects) in the months before hospitalization. Inadequate use of mental health services, then, may be one of the reasons for overutilization of medical services by these patients.

Why might depression be associated with greater use of inpatient and outpatient medical services? Depression in later life is known to be accompanied by an increase in somatic symptoms and hypochondriacal complaints (24, 25). These somatic symptoms may be more acceptable to older patients than psychological complaints. Consequently, physicians may admit these patients to the hospital to evaluate and treat recurrent physical complaints that cannot be resolved in the outpatient setting. This could lead to multiple physician visits before hospitalization and recurrent hospitalizations. Alternatively, depression may impair motivation to recover and to comply with medical treatments, leading to slower recovery and poorer physical health outcomes, which require more physician visits and short-term hospital care.

Because our findings are largely cross-sectional, however, it is not possible to say that depression leads to medical illness with greater use of inpatient and outpatient medical services. The direction of effect could just as well be the opposite. In other words, greater use of inpatient and outpatient medical services might also lead to depression. The frustration of dealing with chronic health problems that are not improving despite multiple visits to doctors and disruptive, expensive short hospital stays may overwhelm some patients' capacity to cope, cause discouragement, and result in depression. This, of course, does not excuse a lack of attention to depression in the medical setting.

Studies of medically ill older patients have now demonstrated that treatment with either antidepressant medication (particularly when guided by psychiatric consultation) (26, 27) or psychotherapy (including patients who are persistently disabled) (28, 29) may reduce both depressive symptoms and their negative effects on health outcomes and medical compliance. Using data from the Medical Outcomes Study, Sturm and Wells (30) examined the costs and health effects of treating depression in mixed-age nonelderly primary care outpatients. While treating depression with increased counseling, use of appropriate antidepressants, and avoidance of benzodiazepines did improve functional outcomes, it also increased the total cost of care. Nevertheless, the value of care was increased because each dollar spent on care provided more benefits in terms of health improvements.

Limitations

The results of this study should be cautiously generalized to elderly patients in other hospital settings. The participants were generally quite ill and were often referred to the Duke hospital because of multiple, complex medical problems. Compared to patients in surrounding community hospitals, the study participants had a lower rate of depressive symptoms, more severe medical illness, and longer hospital stays (mean, 10.2 versus 6.8 days) (31). Health-care-seeking behaviors, likewise, may differ between patients hospitalized at Duke and those admitted to community hospitals.

Diagnosing depression in medically ill older patients can be more difficult than in healthy persons because symptoms of depression are often confounded with those of medical illness (7). We used two methods of counting symptoms for the diagnosis of depressive disorder, the inclusive and DSM-IV etiologic approaches. While the inclusive approach resulted in a higher rate of depression than the etiologic approach, the associations with health service use were largely the same. An important limitation of the study, however, is that we made no attempt to differentiate depressions that represented adjustment reactions to medical illness from autonomous or endogenous depressive disorders.

Conclusions

Hospitalized older patients diagnosed with depression used more inpatient and outpatient medical services during the 3 to 12 months before admission than patients without depression. Differences in service use largely persisted after we controlled for age, sex, race, education, and severity of medical illness at the time of index admission. Alternatively, we could say that hospitalized patients who used more inpatient and outpatient medical services during the months before admission were found to have more depression than those who used fewer medical services. Future prospective studies will need to sort out this “chicken-or-egg” problem, e.g., whether depression leads to greater health service use or vice versa. In any case, the depressed patients in this study made no more visits to mental-health specialists within the months before admission (despite nearly 5 months of depressive symptoms) than did nondepressed patients, with both groups averaging less than one visit every 3 months. These results underscore the need for primary care physicians and third-party payers to invest time and resources in identifying and treating depression in this population. The findings also suggest that treatment with antidepressants alone is likely to be an incomplete solution.

|

Received Feb. 3, 1997; revisions received July 8, Oct. 6, and Nov. 3, 1997; accepted Dec. 1, 1997. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine and the Division of Biometry, Duke University Medical Center. Address reprint requests to Dr. Koenig, Box 3400, Duke Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710; [email protected] (e-mail). Funded by NIMH Clinical Mental Health Academic Award MH-01138 to Dr. Koenig and in part by Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Centers grant AG-11268 from the National Institute on Aging.

FIGURE 1. Classification of Hospitalized Medically Ill Elderly Patients as Depressed “Cases” or Nondepressed “Controls” With the Inclusive Methoda

aWithout regard to presumed etiology. “Case”: score of 16 or higher on the CES-D Scale, score of 11 or higher on the Hamilton depression scale, and three or more DIS criterion symptoms lasting 2 weeks or more during the past month out of 13 criterion symptoms—nine traditional plus four substitute). “Control”: score of 10 or less on the CES-D Scale, score of 10 or less on the Hamilton depression scale, and two or fewer DIS criterion symptoms (out of 13). “Major depression”: 2 weeks or more of depressed mood or anhedonia within past month, along with 2 weeks or more of four other DIS criterion symptoms (out of nine). “Minor depression”: 2 weeks or more within the past month of 1) depressed mood or anhedonia and at least one other criterion symptom (but fewer than four symptoms) or 2) three or more criterion symptoms in the absence of depressed mood or anhedonia.

bNineteen of these patients had Hamilton depression ratings but did not meet the criteria involving CES-D Scale score and number of DIS criterion symptoms.

1 US Senate Special Committee on Aging: Aging America: Trends and Projections. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, 1987–1988, p 11Google Scholar

2 Health: United States 1995: DHHS Publication PHS-96-1232. Hyattsville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics, 1996, p 263Google Scholar

3 Koenig H, Meador K, Cohen H, Blazer D: Depression in elderly hospitalized patients with medical illness. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:1929–1936Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Koenig H, Meador K, Shelp F, Goli V, Cohen H, Blazer D: Major depressive disorders in hospitalized medically ill men: comparison of younger and older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39:881–890Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Koenig HG, George LK, Peterson BL, Pieper CF: Depression in medically ill hospitalized older adults: prevalence, characteristics, and course of symptoms according to six diagnostic schemes. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1376–1383Link, Google Scholar

6 Rapp S, Parisi S, Wallace C: Comorbid psychiatric disorders in elderly medical inpatients: a 1-year prospective study. J Am Ger~iatr Soc 1991; 39:124–131Crossref, Google Scholar

7 Rapp S, Walsh D, Parisi S, Wallace C: Detecting depression in elderly medical inpatients. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:509–515Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Koenig HG, George LK, Meador KG: Use of antidepressants by nonpsychiatrists in the treatment of medically ill hospitalized depressed elderly patients. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1369–1375Link, Google Scholar

9 Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Lipscomb P, Russo J, Wagner E, Polk E: Distressed high utilizers of medical care: DSM-III-R diagnoses and treatment needs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1990; 12:355–362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Souetre E, Lozet H, Cimarosti I, Martin P: Cost of anxiety disorders: impact of co-morbidity. J Psychosom Res 1994; 38:151–160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W: Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:352–357Link, Google Scholar

12 Fulop G, Strain JJ, Vita J, Lyons JS, Hammer JS: Impact of psychiatric comorbidity on length of hospital stay for medical/surgical patients: a preliminary report. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:878–882Link, Google Scholar

13 Koenig HG, Shelp F, Goli V, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG: Survival and healthcare utilization in elderly medical inpatients with major depression. J Am Geriatr Soc 1989; 37:599–606Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Mossey JM, Knott K, Craik R: The effects of persistent depressive symptoms on hip fracture recovery. J Gerontol 1990; 45:M163–M168Google Scholar

15 Parikh R, Robinson R, Lipsey J, Starkstein S, Fedoroff J, Price T: The impact of post-stroke depression on recovery in activities of daily living over a 2-year follow-up. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:785–789Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Applied Psychol Measurement 1977; 1:385–401Crossref, Google Scholar

17 Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Koenig HG, Pappas P, Holsinger T, Bachar JR: Assessing diagnostic approaches to depression in medically ill older adults: how reliably can mental health professionals make judgments about the cause of symptoms? J Am Geriatr Soc 1995; 43:472–478Google Scholar

19 Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Conwell Y, Forbes NT, Cox C, Caine ED: Validation of a mea~sure of physical illness burden at autopsy: the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993; 41:38–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 SAS/STAT User's Guide, version 6, 4th ed, vol 2. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1994Google Scholar

22 Establishment of Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (EPESE): DHHS, PHS, NIH, and NIA Sponsored Piedmont Health Survey of the Elderly (OMB 0925-0267). Durham, NC, Duke University Medical Center, Center for Aging, 1985–1986Google Scholar

23 Kunkel SR, Applebaum RA: Estimating the prevalence of long-term disability for an aging society. J Gerontol 1992; 47:S253–S260Google Scholar

24 De Alarcon R: Hypochondriasis and depression in the aged. Ger~ontol Clin (Basel) 1964; 6:266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Busse EW, Blazer DG: Disorders related to biological functioning, in Handbook of Geriatric Psychiatry. Edited by Busse EW, Blazer DG. New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1980, pp 390–414Google Scholar

26 Schwartz J, Speed N, Clavier E: Antidepressant side effects in the medically ill: the value of psychiatric consultation. Int J Psychiatry Med 1988; 18:235–241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Borson S, McDonald GJ, Gayle T, Deffenbach M: Improvement in mood, physical symptoms, and function with nortriptyline for depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Psychosomatics 1992; 33:190–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Hengeveld MW, Ancion FA, Rooijmans H: Psychiatric consultations with depressed medical inpatients: a randomized controlled cost-effectiveness study. Int J Psychiatry Med 1988; 18:33–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Kemp BJ, Corgiat M, Catherine G: Effects of brief cognitive-behavioral group psychotherapy on older persons with and without disabling illness. Behavior, Health, and Aging 1991–1992; 2:21–28Google Scholar

30 Sturm R, Wells KB: How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA 1995; 273:51–58Google Scholar

31 Koenig HG, Gittelman D, Branski S, Brown S, Stone P, Ostrow B: Depressive symptoms in elderly medical-surgical patients hospitalized in community settings. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 6:14–23Crossref, Google Scholar