Lifetime and Twelve-Month Prevalence Rates of Major Depressive Episodes and Dysthymia Among Chinese Americans in Los Angeles

Abstract

Objective:The authors’ goal was to estimate the lifetime and 12-month rates of major depressive episodes and dysthymia for Chinese Americans who reside in Los Angeles. This effort, the Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study, is the first large-scale community psychiatric epidemiological study on an Asian American ethnic group that used DSM-III-R criteria for major depressive episodes and dysthymia.Method:A multi-stage sampling design was used to select respondents for participation in the survey. The sample included 1,747 adults, 18–65 years of age, who resided in Los Angeles County and who spoke English, Mandarin, or Cantonese.Results:Approximately 6.9% of the respondents had experienced an episode of major depression and 5.2% had had dysthymia in their lifetime. The 12-month rates of depressive episode and dysthymia were 3.4% and 0.9%, respectively. The most consistent correlate of lifetime and 12-month depressive episode and dysthymia was social stress, measured by past traumatic events and recent negative life events. Conclusions:The Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study provides a rare opportunity to investigate the heterogeneity within a single Asian American ethnic group, Chinese Americans, and to identify the subgroups among Chinese Americans who may be most at risk for mental health problems. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1407-1414

The Global Burden of Disease study conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) (1) recently assessed the extent of disability (measured by number of work days lost) and mortality associated with noncommunicable diseases in different countries. The study concluded that depression is one of the most debilitating health problems in the world. In 1990, depression ranked fourth among all diseases (after lower respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, and conditions arising during the perinatal period). The WHO researchers predicted that, by the year 2020, depression will rank second (after heart disease), accounting for 15% of the disease burden in the world (2). Depression is also a common illness in the United States: the National Comorbidity Survey (2) estimated that 17% of all American adults have experienced a major depressive episode in their lifetime. People who have a depressive disorder experience severe limitations in their physical and social functioning that are much worse than those of patients who suffer from chronic health conditions such as hypertension, advanced coronary artery disease, lung problems, and back problems (3).

Despite the large volume of studies that have documented the level of depressive symptoms and the rates of depressive disorders in the past two decades, little information is available about the rates and correlates of depressive disorders among Asian Americans (4). The relative absence of information about Asian Americans is troubling because the empirical literature has not matched the growth of the population from 1970 to 1990. There were about 7 million Asian Americans in 1990, and the population is expected to continue to increase (5). By the year 2025, demographers predict that the population will triple in size (6). Despite the growth and the increased presence of Asian American ethnic groups in cities across the United States, we know very little about their health and well-being.

Many of our estimates about psychiatric problems among Asian Americans come from treatment studies or investigations that used symptom scales (7). Past studies using treatment data showed that Asian Americans are underrepresented in mental hospitals and outpatient clinics (8, 9). The use of treatment data has been especially popular for estimating prevalence and need among ethnic minority populations, where the costs associated with sampling rare (or small) populations can be quite high. Data drawn from treatment facilities can provide an accumulation of large samples of ethnic minority consumers (especially if the data are amassed over time) and easily codified clinical data. On the other hand, aside from issues pertinent to reliability and validity of clinic record data, treatment statistics give a biased estimate when used to appraise the prevalence of mental disorders in the community. This appears to be especially true for ethnic minority groups, many of whom experience barriers to service access and use (10). As more community surveys have been conducted to estimate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders, the results indicate that treatment statistics severely underestimate the level of need for mental health services in the community (11, 12).

Despite the promise and appeal of survey research, only limited numbers of community studies have been conducted on Asian American ethnic groups. Some critical methodological problems have hampered mental health research in Asian American communities. First, Asian Americans have often been considered a homogenous category in large-scale studies, and this assumption ignores the diversity of Asian American groups. More than 20 Asian American ethnic groups have been identified by the United States Bureau of the Census (13). Failure to make distinctions among specific Asian American groups overlooks considerable historical, social, and cultural differences among groups and leads to faulty conclusions about the need for mental health services (14-16). Second, when specific Asian American groups are differentiated, the sample sizes for each group are often too small to make accurate prevalence estimates or to conduct sophisticated analyses of the data (17). Third, Asian American respondents in community surveys are often chosen from a nonrandom sampling frame, such as telephone directories, ethnic association lists, and snowball samples (18). These sampling techniques are understandable given the relatively small population sizes and geographic dispersion of Asian American groups. However, such sampling strategies detract from a study’s findings because of the imprecise nature of the respondent selection.

In this paper we report on a study that systematically considered the cited methodological obstacles. We describe the prevalence and correlates of major depressive episode and dysthymia among Chinese Americans in Los Angeles. Although Chinese Americans are not representative of all Asian Americans, they provide a well-defined target group for generalizations that emerge from the analyses. Our investigation also applied a sophisticated sampling design and set of procedures to select respondents for the study. We used DSM-III-R criteria to estimate the prevalence of depression and dysthymia. Most studies on depression in Asian Americans have used symptom scales. Although the use of symptom scales provide useful data, they are often general indicators of psychological distress or demoralization rather than a single diagnostic category. Prevalence estimates of depression using standardized criteria based on DSM-III-R for Asian Americans are generally lacking. Therefore, in this paper we report on the prevalence rates of major depressive episode and dysthymia using DSM-III-R criteria among Chinese Americans residing in Los Angeles.

METHOD

Sample

Data are from the Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study, a strata-cluster survey conducted in 1993–1994 in the greater Los Angeles area. The survey’s three-stage probability sample of 1,747 Chinese American households generally represents the Chinese American population residing in the area. The three-stage sampling procedure was designed to 1) select tracts from the 1,652 census tracts in Los Angeles County, which was cross-stratified by the percent of Chinese American households in census tracts, by the median income for Asian Pacific households in tracts, and by the percent of the race-ethnicity composition in the tracts, 2) randomly select 12 blocks within each of the tracts, and 3) randomly select four households within each of the blocks. Selection in the first two stages was designed with probabilities proportional to size, such that even though selection probabilities varied within each stage, the ultimate selection probabilities were the same for all Chinese households.

According to the 1990 census, Chinese Americans represented less than 3% of the total population of Los Angeles County. To make the survey cost-effective and increase the probability of locating a Chinese American household, only the tracts where at least 6% of the population was composed of Chinese Americans were sampled. As a result, the Chinese American population in these selected tracts varied from 6% to 72.3%. The percent of the foreign-born of all ethnicities in the tracts varied from 14% to 82%. The average Asian Pacific household income in these tracts varied from about $3,000 to more than $108,000.

Data Collection

Bilingual interviewers, fluent in English and Mandarin or Cantonese, were recruited for this study. Whenever possible, interviewers were recruited from areas within the proximity of the sampled census tract, which helped ensure familiarity with the neighborhoods while gaining efficiency in travel time and mileage. All recruits were screened for suitability for interviewing, reading and writing ability in both languages, access to transportation, and style of presentation. In addition, the interviewers were lay interviewers, and most of them had at least some college education.

The interviews were conducted in English, Mandarin, or Cantonese depending on the respondent’s language preference. The interview process lasted approximately 90 minutes. Data collection began in April 1993 and was completed in August 1994. A total of 16,916 households were visited and screened to locate eligible respondents. Eligible individuals included Chinese Americans, 18–65 years of age, who resided in Los Angeles County. One eligible person within each eligible household was randomly selected for the interview. Of the eligible respondents, 1,747 interviews were completed, which resulted in an 82% response rate. The sample size was based on an estimate of the proportion of respondents who were likely to have experienced a depressive episode in their lifetime. After complete description of the study to respondents, written informed consent was obtained.

Diagnostic Measure

The University of Michigan’s version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview was used as the major diagnostic instrument (2). The Composite International Diagnostic Interview is a structured interview schedule based primarily on the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) and designed to be used by trained interviewers who are nonclinicians. Computer algorithms are used to construct clinical diagnoses based on the responses to the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. The Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study focused on a few major diagnoses, including affective disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol abuse or dependence, and smoking. This paper reports only on affective disorders.

The substantive methodological work that has taken place on the DIS in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China suggests that when the DIS is modified for a Chinese sample, the instrument has high reliability and validity for most diagnoses, including mood disorders (19-21). There is also some evidence that DSM-III-R diagnoses generated by the DIS for schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, and depressive disorders are compatible with the Chinese classification of major disorders (22). The Composite International Diagnostic Interview was originally designed to estimate the prevalence of specific disorders across different countries or geographic regions, and it is particularly useful in describing the co-occurrence of two or more disorders (23). It has demonstrated good interrater reliability (24), test-retest reliability (26), and validity for almost all diagnoses (25, 26). One noticeable difference between the University of Michigan version and the original Composite International Diagnostic Interview is the placement of the lifetime review section at the beginning of the diagnostic section before any probing questions are asked. This modification is in response to a common finding that respondents may underreport stem questions when they recognize that positive responses lead to more detailed questions (2).

Before translating the Composite International Diagnostic Interview into Chinese, we initiated a series of focus groups to determine whether the idioms used for the expression of depressive symptoms were meaningful to Chinese American respondents. Where potential problem words and phrases were identified, additional probes were developed to supplement the interview that assisted respondents in understanding the meaning of key words or phrases. The final instrument was translated and back-translated several times to ensure that the different language versions maintained consistency in meaning for the questions and response categories within the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Analysis Procedures

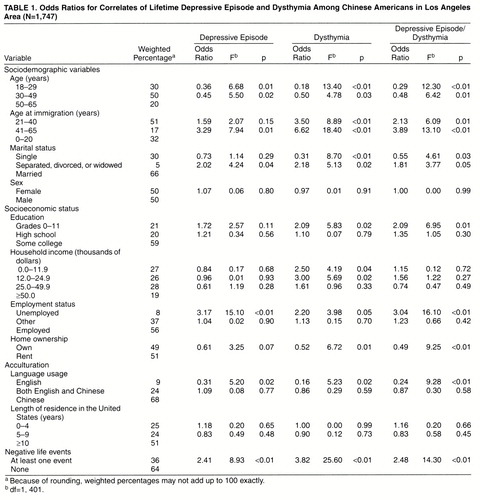

Weights were applied to the sample data to adjust for demographic variables, nonresponse rates, and the differential probabilities of selection within the household. In the following analyses, only weighted data are used. The weighted frequencies for the different demographic variables are included in tables 1 and 2. To adjust for the survey sample design, Taylor linearization (27) was imposed to estimate the standard errors. Wald statistics based on these adjusted standard errors were used for significance tests. Binomial logistic regression was used to describe the differences among subgroups of Chinese Americans who had a depressive episode or dysthymia. The weighted maximum-likelihood method was used to estimate the parameters and standard errors from which the odds ratios, Wald F statistic, and probability levels were calculated. In this paper, we make assessments of statistical significance using a probability level of 0.05. However, the tables in this paper display the Wald F statistic and the actual probability levels for readers who wish to use other statistical criteria to judge significance.

Limitations

The Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study has at least two limitations common to cross-sectional psychiatric epidemiological surveys. First, the diagnostic questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview are based on retrospective accounts of people’s experiences. Recall may be a problem for some respondents, especially for older adults who try to remember the symptoms that may have occurred quite early in their lives. Second, while intensive training and supervision can assist lay interviewers to administer the Composite International Diagnostic Interview properly, the diagnoses that result from this study may not have the same level of accuracy as those reached by a trained clinician (2).

This study also has two additional limitations due to the unique nature of the sample. Because of the complexities of sampling a relatively rare population such as Chinese Americans in Los Angeles County, some tradeoffs in the sampling design were made. If unlimited resources were available for this study, it would be possible to ensure that all Chinese Americans living in Los Angeles had an equal probability of being selected for inclusion in the survey. However, since the resources for the survey were limited, some decisions were made to capture a sizable proportion of the Chinese American population in Los Angeles and still control the screening necessary to find eligible respondents. Accordingly, we limited the study to geographic areas (census tracts) where Chinese Americans represented at least 6% of the population. Going below this figure dramatically increased the cost of screening. The 6% criterion still provided coverage of approximately 60% of the Chinese American population in Los Angeles. The sampling design constrains the extent that we can draw conclusions regarding all Chinese Americans living in Los Angeles. The sampling design excludes Chinese Americans who live in low-density Chinese American geographic areas and, thus, tend to be native-born. We examined whether density affected the lifetime and current prevalence rates within our sample. No statistically significant differences (p ≤0.05) were found in rates of depression and dysthymia among different levels of density.

The final limitation is in the use of a diagnostic instrument using DSM-III-R criteria for a sample, largely consisting of immigrants, who come from a country that is culturally and linguistically different from the United States. As stated earlier, previous work suggests that standardized lay interviews have been quite effective in reaching valid diagnoses of mood disorders. However, until more investigations are conducted on the validity of various diagnoses, the results of Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study should be interpreted with caution. In an attempt to understand cultural variations in the expression of distress, the Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study also included neurasthenia, a mental health problem that is common in Chinese-speaking countries. Some initial results from the analyses of neurasthenia have been presented elsewhere (28). In the current paper, we limit our analyses to the study of depressive episodes and dysthymia. Despite the limitations cited, the Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study used methods common to community psychiatric epidemiological surveys and represents one of the most sophisticated epidemiological studies of an Asian American ethnic group.

RESULTS

This paper reports the prevalence rates for major depressive episode and dysthymia. The occurrence of at least one major depressive episode is an essential feature for a diagnosis for major depressive disorder. Lifetime rates refer to the proportion of respondents who reported having experienced the problem ever in their lifetime, and 12-month prevalence rates are the proportion of respondents who experienced the problem sometime during the 12 months before the interview. The lifetime rate of major depression episode was 6.9%; 3.4% of the respondents had an episode in the past 12 months. Approximately 5.2% of the respondents experienced dysthymia in their lifetime; 0.9% had experienced it within 12 months of the interview. The National Comorbidity Survey (2), using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, reported much higher rates of depressive episodes: a lifetime rate of 17.1% and a 12-month rate of 10.3%. However, the National Comorbidity Survey rates for lifetime (6.4%) and current (2.5%) dysthymia were relatively closer to the estimates found in this study, which suggests that the experience of sadness may be more chronic than episodic for Chinese Americans, many of whom are immigrants.

Table 1 displays the odds ratios for the lifetime occurrence of a depressive episode and dysthymia. Among the sociodemographic variables, marital status has the strongest and most consistent association with the lifetime occurrence of a major depressive episode. Age shows some association with depression and dysthymia in that respondents in the younger age groups (ages 18–29 and 30–49) are less likely to have experienced mood disorders than the oldest age group in our sample (ages 50–65). Since many of the respondents were immigrants, the age variable is confounded with age at immigration. Table 1 shows that age at immigration is associated with depressive episodes and dysthymia. Accordingly, there may be strong cohort differences based on the timing of immigration rather than simply an age effect.

The most perplexing of the results in table 1 is the absence of an association between sex and depressive episodes and dysthymia. In most community studies, women have consistently higher rates of mood disorders than men. In the National Comorbidity Survey (2), for example, women were 1.8 times more likely to have a lifetime mood disorder than men. To explore this anomaly further, we examined sex differences among respondents at different acculturation levels. We used an acculturation scale that included items on language use, ethnicity of the workplace, and types of foods eaten (29). A high score indicated a greater exposure to American life styles and a low score indicated a greater exposure to Chinese culture. To explore how acculturation and sex intersect to explain the rates of mood disorders among Chinese men and women, we divided the sample into two groups based on a midpoint on the acculturation scale score. Although the selection of the midpoint is somewhat arbitrary, it did create two groups that differed in acculturation levels. The mean score of the group on the top half of the scale (mean=3.00, SD=0.42) was significantly higher than the mean score of the group on the bottom half (mean=1.76, SD=0.30) (F=1735.36, df=1, 1642, p=0.0001). We examined the association between sex and depression and dysthymia in these two groups. Since women are expected to have a higher rate of depression, we used a one-tailed test of the odds ratios. Within the high-acculturation-score group, women were 3.1 times more likely than men to have dysthymia in their lifetime (Wald F=1.76, df=1, 401, p=0.10) and 2.16 times more likely than men to have a lifetime depressive episode (Wald F=1.15, df=1, 401, p=0.14). In the low-acculturation-score group, women did not differ significantly from men in lifetime depressive episodes (odds ratio=0.99, Wald F=0.00, df=1, 401, p=0.97) and dysthymia (odds ratio=0.91, Wald F=0.09, df=1, 401, p=0.76). Two explanations are plausible. First, it is possible that women who have low acculturation levels may be protected against the onset of depressive episodes. Second, it is also likely that sex differences may become pronounced as Chinese immigrants become acculturated. Although these explanations are not mutually exclusive, our data do not allow us to examine this issue extensively.

The socioeconomic status variables are associated with either lifetime depression or dysthymia. Between the two immigration variables, only language use is associated with depressive episodes and dysthymia. Among all correlates listed in table 1, negative life events has one of the strongest and most consistent associations with the lifetime occurrence of major depressive episode and dysthymia. The life events measure is an inventory of 10 traumatic events (combat experience; life-threatening accident; involvement in a natural disaster; witnessing someone being badly injured or killed, raped, sexually molested, physically attacked, or assaulted; physical abuse as a child; neglect as a child; and threat with a weapon). The experience of at least one negative life event is associated with an elevated risk for depressive episode and dysthymia.

Table 2 displays the association of the sociodemographic, socioeconomic status, immigration, and life event variables with 12-month major depressive episode and dysthymia. Age and sex do not show an association with 12-month depressive episode and dysthymia. Marital status is associated with dysthymia but not with depressive episode.

Among the socioeconomic status variables, income and employment status are associated with current depressive episode and dysthymia. Language and length of time in the United States are not associated with either disorder. Recent negative life events (e.g., breakup of a close friendship, separation from a loved one, having been robbed or burglarized, having one’s driver’s license suspended, suing someone, being sued by someone, experiencing serious trouble with police or law, death of close friends or relatives) has a strong association with both disorders.

DISCUSSION

Two divergent hypotheses are presented when predictions are made about the prevalence of psychiatric problems among Asian Americans. The first hypothesis suggests that rates will be high because a large proportion of Asian Americans are immigrants who will undergo difficult transitions in their adjustment to American society. Indeed, studies have found that some Asian American ethnic groups have higher symptom scores than whites (4). The second hypothesis argues that the rates of mood disorders will be low because Asian Americans, like their counterparts in other countries, are likely to express their problems in behavioral or somatic terms rather than as emotional ones. Available evidence suggests that the rates of mood disorders are quite low in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China (30).

Findings from the Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study suggest that, when DSM-III-R criteria are used, the prevalence estimates of depressive episodes and dysthymia are more complex than the hypotheses that have been advanced. When compared with a national estimate, the National Comorbidity Survey (2), which used the same diagnostic measure (the Composite International Diagnostic Interview), Chinese Americans have a much lower rate of major depressive episode. However, it is equally evident that Chinese Americans are not adverse to expressing problems in emotional idioms. This is supported by the finding of similar rates of lifetime and current dysthymia in our study and the National Comorbidity Survey.

Except for marital status and employement status, none of the sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables shows a strong and consistent association with both lifetime and current major depressive episode and dysthymia. The lack of an association with sex, household income, and education warrants some comment. Education and income may not be consistently associated with depression and dysthymia in our sample for two reasons. First, past empirical studies do not actually show a stable association between socioeconomic status and depression. Although the inverse association between socioeconomic status and mental illness is widely known, socioeconomic status has unique associations with discrete disorders. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (31), for example, found that socioeconomic status was not associated with depression but had an inverse association with lifetime rates of alcohol abuse. The National Comorbidity Survey (2) demonstrated that people in the lowest income levels (compared with those in the highest) were most at risk for affective disorders and that socioeconomic status was more strongly linked to anxiety disorders than to affective disorders. The inverse association between socioeconomic status and depression has not been found consistently for all ethnic groups (32). Second, commonly used measures of socioeconomic status, such as income and education, may not fully capture the important dimensions of status among immigrant groups. Although some Chinese immigrants may have high levels of education when they arrive in the United States, it may not lead to high-paying jobs because employers may not value education gained in another country as much as education gained in the United States. Moreover, language difficulties and discrimination against immigrants may prevent them from accruing the benefits of higher education. Finally, although income typically measures the annual resources available to a person, it does not fully capture other economic resources that people can rely on (e.g., savings, home ownership) (33). Some immigrants in low-income brackets may be quite wealthy, and some who have high annual incomes may use most of their resources to accommodate their entry into the United States.

The absence of an association between sex and depressive episodes and dysthymia is striking. Most studies tend to show that women have significantly higher rates of depression than men. Although the precise reason for sex differences is open for debate, women tend to show a 2-to-1 margin in depression across a number of countries and studies. However, some exceptions to this pattern can be found. Brown and associates (34) found no association between sex and 12-month rates of depression among African Americans in Maryland. No sex association was found among Southeast Asian refugees in Canada (35) and among Korean Americans living in Chicago (36). The Taiwan study (30) found that women had slightly elevated rates of depression and dysthymia but that the rates for both men and women were low and that the differences did not appear statistically significant. In a reanalysis of the ECA data (37), Jewish men had a similar rate of major depression as Jewish women, although other religious groups (e.g., Catholics, Protestants, and non-Jews) had the expected 2:1 female-male ratio for depression. Some of our preliminary analyses suggest that acculturation may partly explain the absence of an overall sex difference. Sex differences seem to appear as Chinese immigrants acculturate to life in the United States. Another explanation is that when the rate of alcohol consumption is low, as it is among Chinese Americans (38), sex differences in mood disorders may be diminished (37).

There are some similarities and differences between our findings and those of previous studies regarding the rates and correlates of major depressive episode and dysthymia. Although the Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study focuses exclusively on Chinese Americans, much diversity exists within this ethnic category. For example, Chinese Americans who immigrate to the United States come from countries that are different in their sociopolitical environment—such as China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Moreover, large numbers of Chinese sought refuge from Vietnam during and after the Vietnam conflict. The Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study provides a rare opportunity to investigate the heterogeneity among Chinese Americans and to identify subgroups who may be most at risk for mental health problems.

Received July 7, 1997; revisions received Sept. 30 and Dec. 22, 1997, and March 9, 1998; accepted April 2, 1998. From the Neuropsychiatric Institute and the Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Takeuchi, 10920 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90024-6505; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-47460, MH-47193, and MH-44331.

|

|

1. Murray CJ, Lopez AD: The Global Burden of Disease. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:914–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Vega W, Rumbaut R: Ethnic minorities and mental health. Annual Rev Sociology 1991; 7:351–383Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Asians in America: 1990 Census Classification by States. San Francisco, Asian Week, 1991Google Scholar

6. Lewit EM, Baker EM: Race and ethnicity: changes for children. Critical Health Issues for Children 1994; 4:134–144Google Scholar

7. Takeuchi D, Uehara E: Ethnic minority mental health services: current research and future conceptual directions, in Mental Health Services: A Public Health Perspective. Edited by Levin BL, Petrila J. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996, pp 63–96Google Scholar

8. Snowden LR, Cheung F: Use of inpatient mental health services by members of ethnic minority groups. Am Psychologist 1990; 45:347–355Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu L, Takeuchi D, Zane N: Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: a test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59:533–540Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Robins LN, Regier DA (eds): Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

11. Dohrenwend BP, Dowhrenwend BS: Social and cultural influences on psychopathology. Annu Rev Psychol 1974; 25:417–452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Takeuchi D, Leaf P, Kuo HS: Ethnic differences in the perception of barriers to help-seeking. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1988; 23:273–280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Race and Hispanic Origin, vol 2. Washington, DC, US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, 1991, pp 1–8Google Scholar

14. Sue S, Zane N, Young K: Research on psychotherapy with culturally diverse populations, in Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 4th ed. Edited by Bergin AE, Garfield SL. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1994, pp 783–817Google Scholar

15. Uehara E, Takeuchi D, Smukler M: Some effects of combining disparate groups in the analysis of ethnic differences: variations among Asian American mental health consumers in level of community functioning. Am J Community Psychiatry 1994; 22:83–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Sue S, Sue D, Sue L, Takeuchi D: Asian American psychopathology. Cultural Diversity and Ment Health 1995; 1:39–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Takeuchi D,Young K: Overview of Asian and Pacific American health issues, in Confronting Critical Health Issues Among Asian and Pacific Islanders. Edited by Zane N, Takeuchi D, Young K. San Francisco, Sage Publications, 1994, pp 3–21Google Scholar

18. Yu ESH, Liu WT: Methodological issues. Ibid, pp 22–50Google Scholar

19. Hwu HG, Yeh EK, Chang LY: Chinese Diagnostic Interview Schedule, I: agreement with psychiatrist’s diagnosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986; 73:225–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hwu HG, Yeh EK, Chang LY, Yeh YL: Chinese Diagnostic Interview Schedule, II: a validity study on estimation of lifetime prevalence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986; 73:348–357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hwu HG, Yeh EK, Chang LY: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan defined by the Chinese Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 79:136–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Zheng YP, Lin KM, Zhao JP, Zhang MY, Yong D: Comparative study of diagnostic systems: Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders-Second Edition versus DSM-III-R. Compr Psychiatry 1994; 35:441–449Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, Sartorius N, Towle LH: The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1069–1077Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Semler G, von Cranach M, Wittchen H (eds): Comparisons Between the Composite International Diagnostic Interview and the Present State Examination: Report to the WHO/ADAMHA Task Force on Instrument Development. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1987Google Scholar

25. Spengler P, Wittchen H: Procedural validity of standardized symptom questions for the assessment of psychotic symptoms: a comparison of the CIDI with two clinical methods. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 29:309–322Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Janca A, Robins L, Cottler L, Early T: Clinical observation of CIDI assessments: an analysis of the CIDI field trials. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:815–818Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Binder DA: On the variances of asymptotically normal estimators from complex surveys. Int Statistical Rev 1983; 15:279–292Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Zheng Y-P, Lin K-M, Takeuchi D, Kurasaki KS, Wang Y, Cheung F: An epidemiological study of neurasthenia in Chinese-Americans in Los Angeles. Compr Psychiatry 1997; 38:249–259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Burnam A, Hough RL, Escobar JI, Karno M, Timbers DM, Telles CA, Locke BZ: Acculturation and lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans. J Health Soc Behav 1988; 28:89–102Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Horwath E, Weissman MM: Epidemiology of depression and anxiety disorders, in Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Edited by Tsuang MT, Tohen M, Zahner GE. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1995, pp 317–344Google Scholar

31. Williams DR, Takeuchi DT, Adair R: Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorder among blacks and whites. Social Forum 1992; 71:179–194Google Scholar

32. Dohrenwend B: Socioeconomic status (SES) and psychiatric disorders. Soc Psychiatry and Psychiatr Epidemiol 1990; 25:41–47Medline, Google Scholar

33. Williams DR, Collins C: Socioeconomic differentials in health: a review and redirection. Annual Rev Sociology 1995; 21:349–386Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Brown DR, Ahmed F, Gary LE, Milburn NG: Major depression in a community sample of African Americans. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:373–378Link, Google Scholar

35. Beiser M, Turner RJ: Catastrophic stress and factors affecting its consequences among Southeast Asian refugees. Soc Sci Med 1989; 28:183–195Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Hurh WM, Kim KC: Correlates of Korean immigrants’ mental health. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:703–711Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Levav I, Kohn R, Golding JM, Weissman MM: Vulnerability of Jews to affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:941–947Link, Google Scholar

38. Zane NWS, Kim JH: Substance use and abuse, in Confronting Critical Health Issues of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. Edited by Zane NWS, Takeuchi D, Young K. San Francisco, Sage Publications, 1994, pp 316–343Google Scholar