Efficacy and Tolerability of Carbamazepine for Agitation and Aggression in Dementia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of carbamazepine in the treatment of agitation and aggression associated with dementia were assessed. METHOD: In a 6-week, randomized, multisite, parallel-group study of 51 nursing home patients with agitation and dementia, individualized doses of carbamazepine were compared with placebo. Except for a physician monitor and a pharmacist, all participants were blind to treatment. The primary outcome measures were the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) global improvement rating. Secondary measures included measures of behavior, aggression, cognition, functional status, staff time, safety, and tolerability. Intent-to-treat analysis was performed. RESULTS: The modal carbamazepine dose at 6 weeks was 300 mg/day, and a mean serum level of 5.3 μg/ml was achieved. The study was terminated after a planned interim analysis showed that carbamazepine provided more benefit than did placebo. Over 6 weeks the mean total BPRS score decreased 7.7 points for the carbamazepine group and 0.9 for the placebo group, and the weekly scores showed a gradual divergence between the two groups. CGI ratings showed global improvement in 77% of the patients taking carbamazepine and 21% of those taking placebo. Secondary analyses confirmed that the positive changes were due to decreased agitation and aggression. The drug was generally well tolerated, and no change in cognition or functional status occurred. The perception of staff time needed to manage agitation showed a decrease for carbamazepine but not placebo. CONCLUSIONS: This controlled study showed significant short-term efficacy of carbamazepine for agitation with generally good safety and tolerability. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:54–61)

Awide range of psychopathological signs and symptoms is associated with dementia, occurring in up to 90% of patients at some point in the course of illness (1–3). These include “agitation,” a descriptive term applied to a heterogeneous group of inappropriate verbal, vocal, or motor activities that are not explained by medical problems, social or environmental disruption, or apparent needs or confusion (4). The problem is especially prevalent in the nursing home, where as many as 70% of patients have dementia (2, 4–7).

Treatment of agitation entails identification and reversal of physical, environmental, social, and psychiatric precipitants (8). Only when these steps fail should symptomatic pharmacotherapy be considered. Again, the issue is particularly pertinent in the nursing home, where 50% or more of patients receive psychotropics (7, 9). Antipsychotics are used most frequently, but authors of reviews (8, 10) have concluded that the empirical evidence for their efficacy is limited, and toxicity is common. Alternatives, including carbamazepine, have been examined in preliminary studies that did not definitely establish therapeutic efficacy (7). The use of carbamazepine in dementia was originally advocated on the basis of extrapolation from reports that it reduced agitation, aggression, irritability, and impulsivity across a wide range of other clinical disorders. Four case reports and four open studies indicated that carbamazepine was efficacious (see reference 11 for review; 12), while a small controlled study was negative (13). In view of these suggestive findings, we previously performed a nonrandomized, placebo-controlled pilot study of 25 agitated nursing home patients with dementia, which showed evidence of behavioral efficacy along with minimal adverse effects (11).

Using that pilot study as a foundation, we undertook a confirmatory, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study to more definitively address the issue of carbamazepine's efficacy for agitation. Our primary hypothesis was that carbamazepine administration would lead to significantly greater reduction in agitation than would placebo, as determined by using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (14). We also hypothesized that this reduction would be captured by a global clinical scale, used as an additional primary outcome measure in order to establish the clinical relevance of changes in the general behavioral measure. Secondary questions addressed possible patterns of response, safety, and tolerability.

METHOD

Subjects and Settings

This study was conducted at four long-term care facilities in Rochester, N.Y., that ranged from 350 to 600 beds. Prospective subjects were referred by their multidisciplinary care teams. Eligible subjects met 1) the criteria for probable or possible Alzheimer's disease of DSM-III-R and of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (15), 2) the DSM-III-R criteria for vascular dementia, or 3) the DSM-III-R criteria for mixed dementias. Both dementia diagnoses were included because the literature suggests that carbamazepine's efficacy for disinhibition and agitation is not restricted to particular diagnoses, because our own pilot data did not suggest a difference in efficacy or toxicity between these dementia diagnoses, and because both diagnoses are common in the nursing home and are frequently associated with agitation (11, 16, 17). Each subject was at least 60 years old; had exhibited agitation for at least 2 weeks and with sufficient intensity to result in a BPRS score of 3 or higher on the tension, hostility, uncooperativeness, or excitement item; was free of acute illness as reflected by medical history, examination, and laboratory testing; and had a designated family member to assist in the consent process. After complete description of the study to the patient and legally authorized caregiver, written informed consent was obtained from each caregiver and, where possible, the patient. Assent was obtained for patients who were unable to provide written informed consent.

For the 43 subjects receiving psychotropics, these were withdrawn for at least 2 weeks before treatment assignment. The behavior problems had to persist at threshold levels in order for the subject to be included in the random treatment assignment. As-needed chloral hydrate was available to all subjects beginning at screening; it was to be ordered at the discretion of the patient's health care team, in doses of 250–500 mg, up to 2 g in 24 hours. Chloral hydrate was selected because of its putatively nonspecific and short-term psychotropic effects and the relatively low incidence of drug-drug interactions (18).

Design

This was a 6-week, randomized, multisite, parallel-group study of placebo versus optimal doses of carbamazepine. The randomization was blocked by site. All participants were blinded to treatment condition with the exception of a physician monitor and a pharmacist, neither of whom had contact with the patient, care team, family, or laboratory personnel. The physician determined the patient's optimal dose on the basis of written reports of adverse effects from the blinded raters and on the basis of confidential laboratory data. Efficacy did not influence dosing decisions. The use of individualized dosing was chosen in view of the limited published data regarding the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of this agent for this population. According to the protocol, the dose began at 100 mg/day and increased by 50 mg every 2–4 days unless side effects occurred, in which case the dose was held steady or, if necessary, decreased by 50 or 100 mg every 2–4 days. In the absence of toxicity, a serum level of 5–8 µg/ml was maintained; otherwise, the highest subtoxic dose was used. After the first 6-week period, the patients underwent a 3-week washout followed by further controlled treatment not described in the present report.

Outcome Variables

Ratings were performed by experienced research nurses who had previously established, and maintained, criterion reliability in use of the BPRS (10% or less deviation from consensus total BPRS scores in group interviews). The total score on the modified form of the BPRS was chosen as a primary outcome measure because it has been used in psychopharmacological and naturalistic studies of persons with dementia, because it has demonstrated validity, reliability, sensitivity (7, 14, 19), and because its use permitted empirically derived sample size projections and comparison of findings with those from prior studies (11, 20). A semistructured interview of the patient was performed, and 18 items were each rated on a scale of 1 (not present) to 7 (extremely severe) (21). Five factors can be derived for geriatric patients: withdrawn/depression, agitation, cognitive dysfunction, hostility/suspiciousness, and psychotic distortion (22). The total BPRS permitted global assessment of psychopathology, while the factors permitted more specific examination of agitated behaviors and other psychopathology. This approach to assessing outcome is supported by work showing that agitated and aggressive behaviors often co-occur with other psychopathological features (1, 6, 17, 23). This instrument was completed weekly. Since the dose could be adjusted during the 6-week period, the primary analysis addressed change in BPRS scores from week 0 to week 6.

The global improvement rating of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (24) was used at week 6 as a global index of efficacy in order to better ascertain the clinical relevance of changes in BPRS scores. Change was rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from “very much improved” to “very much worse.” The CGI also assessed the presence of side effects and whether these were clinically significant.

The Overt Aggression Scale (25) was used to quantify verbal and physical aggressive behaviors. A global index of the severity of aggressive episodes, termed “total aggression score,” was derived from the number of aggressive episodes, their specific nature, and the number of interventions made in response to them. This rating was performed weekly.

The Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (1), modified to increase its sensitivity to change, was included at weeks 0 and 6 as a secondary outcome measure in order to assess this instrument's utility for inclusion in future trials. It consisted of a structured interview of a caregiver that posed 48 questions regarding the frequency of specific behaviors in the past month.

The functional ability of patients, i.e., ability to perform activities of daily living, was assessed at weeks 0 and 6 with the Physical Self Maintenance Scale (26), and cognitive status was assessed by using the Mini-Mental State (27). The number and amounts of doses of as-needed chloral hydrate were recorded. The nurse best acquainted with the patient on the day shift was asked how much extra time was required to manage the patient's behavioral problems in addition to the time necessary to provide routine personal and supportive care (“extra time”). This was coded on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (almost constant). This was included as a preliminary measure of the staff time required to manage such problems.

Health concerns at baseline and throughout the study were coded and rated according to severity (1=minimal, 2=moderate, 3=severe) and duration in days. This permitted an analysis of the frequency of adverse effects and use of an “area under the curve” approach in which the product of the duration of the event (in days) and the severity was used as an overall measure of adverse effects. The following laboratory measures were determined at weeks 0 and 6: CBC with differential count, total iron-binding capacity, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transferase, lactate dehydrogenase, total and direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, electrolytes, glucose, vitamin B12, folate, iron, total protein, and albumin. For patients receiving carbamazepine, CBC with differential and electrolyte and carbamazepine serum levels were determined weekly, and the carbamazepine level was also measured at the end of the study. For patients receiving placebo, a CBC with differential only was determined weekly.

Statistical Analysis

The BPRS data were examined by a t test of within-subject change in total score (week 6 minus week 0); we used a t test version that does not assume equal variance. The other primary variable, the CGI score, was analyzed by using the Mann-Whitney test since this measure is an ordered categorical variable. Confidence intervals were also calculated for the primary variables. The efficacy data were analyzed according to intent-to-treat principles; efficacy measures were obtained at week 6 even for subjects who dropped out (adverse effects were monitored until their resolution). A significance level of 0.05 was used for all analyses. A two-sided test was chosen in order to present the data more conservatively. Second-order analysis of weekly BPRS scores was performed with repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) in order to examine time trends in the two treatment groups. The Huynh-Feldt correction to degrees of freedom is reported for all repeated-measures ANOVAs.

All secondary data were analyzed in a similar fashion, by means of a t test for each continuous variable, a Mann-Whitney test for ordinal or nonnormally distributed data, and the Fisher exact test for comparing ratios with small cell sizes. The sample size computation was based on our prior study of 25 subjects (11). Since that study group was small, and the data were nonnormally distributed, we performed a planned interim efficacy analysis once the 50th subject had completed the current study to ensure the appropriateness of the group size projection. The study was terminated at that point according to predetermined stopping rules (a statistically significant effect on total BPRS and CGI scores in favor of drug, p<0.01). Since the interim analysis was significant with 50 subjects, all primary analyses are based on that group size. The exclusion of the last subject from the primary analysis would have had no effect on the outcome. However, because 51 subjects were randomly assigned, baseline characteristics, secondary outcome measures, and measures of adverse effects are presented for all 51 subjects.

A post hoc analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed on the total BPRS scores by using baseline age, Mini-Mental State score, and Physical Self Maintenance Scale score as covariates in view of baseline differences between the two groups. Finally, additional secondary analyses involved multiple regression models, with preselected independent variables used to determine predictors of efficacy in the carbamazepine group.

RESULTS

Of the 163 subjects screened for the study, 112 were excluded for the following reasons: eligible but caregiver declined (N=26), too agitated to tolerate protocol (N=20), severity of agitation below criterion (N=16), medically unstable (N=15), ineligible dementia diagnosis (N=13), required treatment with other medications not permitted by protocol (N=12), unable to comply with venipuncture or oral medication (N=3), primary physician did not agree (N=3), already receiving carbamazepine (N=2), or lack of family member to provide consent (N=2).

Table 1 summarizes baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study group. The behavioral target symptoms are summarized in table 1 according to the clusters proposed by Cohen-Mansfield (2): 1) repetitive statements, questions, demands, complaints, and screaming (verbal disruption); 2) pacing, trying to leave, handling things inappropriately, and motor stereotypy (physical disruption); 3) undressing or urinating in public and hoarding possessions (social inappropriateness); and 4) hitting, pushing, biting, scratching, kicking, grabbing, throwing, threats, and obscenities (aggression). The carbamazepine-treated group was older, had been institutionalized longer, and was more severely demented according to the Mini-Mental State. It should be noted, however, that the Mini-Mental State has low reliability below a score of 10 (28).

Ten subjects taking placebo and 12 taking carbamazepine received chloral hydrate during the 6-week period. At baseline the patients in the placebo group had received an average of 0.6 (SD=1.2) doses of chloral hydrate (250 mg) in the preceding week, versus 3.5 (SD=4.7) for the drug group. At week 6 these values were 0.5 (SD=1.2) and 1.6 (SD=3.0), respectively (z=1.98, p=0.05). The decrease in the carbamazepine group occurred gradually over the 6 weeks.

There were four dropouts, and all were subjects receiving carbamazepine. One was withdrawn at day 16 because of tics and sedation occurring at a dose of 200 mg/day (serum level=4.4 µg/ml). These disappeared in 48 hours; no psychotropics were used during the next 5 weeks. The second subject, who was severely agitated but had no side effects, was transferred to a short-term psychiatric hospital at day 10, while receiving 200 mg/day of carbamazepine (serum level=4.2 µg/ml). She remained in the hospital for 3 weeks and was treated with modest success with haloperidol and carbamazepine. The third subject was dropped from the study at day 14 by his primary physician and was treated openly with carbamazepine because of persistent agitation, at a dose of 200 mg/day (serum level=4.2 µg/ml). There were no side effects. The fourth subject was dropped at day 36 for agitation (that was improved in our rater's opinion) at a dose of 500 mg/day (serum level=4.1 µg/ml). There were no persistent side effects. He was treated openly with carbamazepine.

The mean daily dose of carbamazepine at week 6 for the group receiving active drug was 304 mg/day (SD=119), the modal dose was 300 mg/day, and the mean serum level was 5.3 µg/ml (SD=1.1, range=3.5–7.6).

Behavioral Data

The mean change in total BPRS score was –7.7 for the carbamazepine group and –0.9 for the placebo group; the difference was significant (table 2). The 95% confidence interval for the difference between the changes in total BPRS score for the drug and placebo groups was 3.3–10.2. Figure 1 presents the total BPRS score at baseline and week 6 for each subject, demonstrating the interindividual variability in baseline scores and in change. A small number of subjects in each group deteriorated behaviorally (i.e., scores increased), the majority of patients taking placebo showed no change as assessed by this method, and the majority of patients taking carbamazepine showed some improvement. The CGI data (table 2) showed that 21% of the patients taking placebo were rated as at least minimally improved, versus 79% who were unchanged or worse, while 77% of the patients taking carbamazepine were rated as at least minimally improved and only 23% were unchanged or worse; the difference was significant. The 95% confidence interval for the difference in CGI score between drug and placebo was 1.0–2.0. When a Bonferroni correction was used by multiplying the p value for the two primary outcome measures by 2, the results remained highly significant.

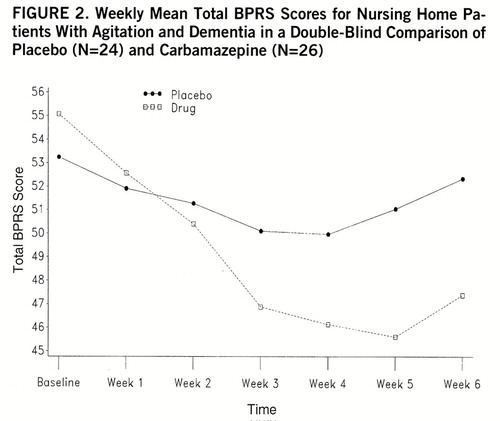

The changes in total BPRS score occurred in an orderly fashion from week to week, an important secondary point illustrated in figure 2. This observation was supported by a repeated-measures ANOVA of the weekly total BPRS data (for the 47 available patients) showing a significant treatment-by-time interaction (F=8.33, df=6,270, Huynh-Feldt epsilon=0.63, p<0.0001).

The changes in total BPRS score and CGI rating indicated a general improvement in behavioral condition but not whether the changes occurred in one or more specific realms. Analysis of the BPRS factor scores indicated that factor 2 (agitation) and factor 4 (hostility) showed significant changes; the others did not. Plots of the weekly scores for these factors were similar to those for the total BPRS score, with similar repeated-measures ANOVA results (treatment-by-time interaction for factor 2: F=7.74, df=6,270, Huynh-Feldt epsilon=0.86, p<0.001; treatment-by-time interaction for factor 4: F=8.12, df=6,270, p<0.0001). In other words, orderly and statistically significant decreases occurred in items representing agitation and aggression but not in items reflecting other clinical domains. Scores on the Overt Aggression Scale showed a significant difference between carbamazepine and placebo (table 2), a similarly orderly decrease in weekly values, and a significant treatment-by-time interaction on repeated-measures ANOVA (F=2.82, df=6,270, Huynh-Feldt epsilon=0.55, p=0.03).

In view of the baseline differences in several characteristics, an ANCOVA of change in total BPRS score was performed with adjustment for age and baseline scores on the Mini-Mental State and Physical Self Maintenance Scale. This showed a highly significant effect of carbamazepine (F=13.68, df=1,44, p=0.0006), with an effect size of –6.5. None of the covariates had a significant effect.

Finally, the total score on the modified Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia showed a significant difference between carbamazepine and placebo (table 2), indicating that this new measure of behavioral change was sufficiently sensitive to capture the clinical change found with more traditional measures.

Cognitive and Functional Status

Average within-patient changes in total Mini-Mental State and Physical Self Maintenance Scale scores for the drug and placebo groups were not significantly different. Specifically, the mean changes from baseline in Physical Self Maintenance Scale score for the placebo and carbamazepine groups, respectively, were –0.3 (SD=1.9) and 0.3 (SD=3.0), and for the Mini-Mental State the changes in scores were –0.2 (SD=3.8) and –0.4 (SD=4.3).

Staff Time Spent

Staff perception of the extra time required to attend to behavioral problems significantly decreased from week 0 to week 6 for the carbamazepine group but not for the placebo group (table 3). Expressed differently, 74% of the patients receiving carbamazepine (20 of 27) required less staff time for management of behaviors, versus 21% of the patients receiving placebo (five of 24).

Adverse Effects

Side effects were significantly more common in the carbamazepine group (16 of 27 patients, 59%) than in the placebo group (seven of 24, 29%) (Fisher exact test, p=0.03), although these were considered clinically significant in only two cases (one patient with tics, one patient with ataxia). Dose reductions related to side effects were necessary for five patients other than the dropouts. Table 4 shows the numbers of patients suffering specific adverse effects and the mean area under the curve for these adverse effects; no side effect occurred significantly more often in the carbamazepine group than in the placebo group, although anecdotes suggested more ataxia and disorientation in the carbamazepine group. There were no differences between the groups in falls with or without injuries; hence, these data were combined. No clinically significant change in any laboratory measure occurred in any individual patient.

Predictors

There was no statistical relationship between change in total BPRS score for the carbamazepine group and any of the following variables: age, gender, dementia diagnosis, site of study, baseline Mini-Mental State or Physical Self Maintenance Scale score, number of medical diagnoses, carbamazepine level at week 6, or total number of doses of chloral hydrate given over 6 weeks. Neither carbamazepine level nor total number of chloral hydrate doses given was correlated with drowsiness, disorientation, ataxia, postural instability, decline in Physical Self Maintenance Scale or Mini-Mental State score, or change in laboratory values.

DISCUSSION

Major Points

The patients in this study were old, frail, medically complex, severely demented, and functionally impaired. They experienced substantial levels of agitation, particularly aggressive behaviors. In short, they were representative of nursing home patients with dementia who are agitated (2, 5–9).

The total BPRS score showed a significantly greater reduction after 6 weeks in the carbamazepine group than in the placebo group. The modal carbamazepine dose at week 6 was 300 mg/day, and the average level was 5.3 µg/ml. The doses and serum levels achieved were similar to results from our pilot study (11). The reduction in total BPRS score developed gradually over 6 weeks in an orderly fashion, a finding that enhances the clinical significance of the change data used in the primary analysis. The change in this general psychopathology index was supported by a highly significant difference in improvement on the CGI between drug and placebo, supporting the clinical relevance of the BPRS change. Analysis of the BPRS factors and secondary behavioral measures indicated that the overall change in behavior resulted from specific effects on agitation and aggression.

The medication had moderate or greater clinical benefit from a global perspective, according to the CGI, for about one-half of the subjects who received it, with minimal benefit in another one-quarter and no benefit in one-quarter. Placebo showed no benefit in about 80% of the cases. These findings suggest that the majority of patients treated with carbamazepine derived clinically meaningful benefit.

The change in agitation in the carbamazepine group was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the staff's perception of the time required to manage the agitation. Such a decrease was not evident in the placebo group. This difference is supported by nonquantitative caregiver impressions that the patients receiving carbamazepine were frequently more engaged in appropriate social activities. If this finding were replicated and extended, it might be possible to demonstrate important cost implications and opportunities to increase staff time for other care needs.

One of the dropouts developed clinically significant tics. Tics have previously been reported to occur with carbamazepine treatment and occurred in one patient in our earlier study (16). Another patient in this study developed substantial ataxia but did not drop out. Some individuals developed drowsiness, disorientation, ataxia, and postural instability with carbamazepine administration, but these effects did not occur significantly more often than with administration of placebo. There was no decline in functional status or cognitive performance. There was no significant change in any laboratory measure. Our controlled data from a total of 76 frail nursing home patients in this study and our earlier one (11) suggest that short-term use of this medication has a relatively benign side effect profile, unlike other agents, especially antipsychotics (10).

Our findings regarding efficacy, safety, and tolerability are consistent with the results from virtually all previous studies of patients with dementia, including our preliminary study (11, 16). The one exception was a 4-week crossover study of a small group of women with only limited agitation, who received uncontrolled amounts of thioridazine in addition to carbamazepine and achieved an average carbamazepine serum level of only 3.4 µg/ml (13).

Possible Mechanisms

The basis for carbamazepine's antiagitation effects is unknown. Candidates include the drug's ability to inhibit limbic kindling or direct neurochemical or electrophysiological effects (29, 30). Some of these mechanisms, especially modulation of γ-aminobutyric acid or serotonin transmission, have been invoked to explain its antiaggression effects in animals (31, 32).

Methodological Issues

Several factors may limit the generalizability of these results, including the relatively small number of subjects, the short duration of treatment, and performance of ratings by a single research team. Multiple dementia diagnoses were permitted, the target symptoms were heterogeneous, the patients suffered multiple medical problems, and numerous nonpsychotropic medications, as well as as-needed chloral hydrate, were administered. The doses of carbamazepine were manipulated by a nonblind physician, which represents a major deviation from usual methods in double-blind trials. However, this approach was deemed necessary because of our need to monitor doses and side effects carefully for these frail patients. Further, we were not confident that using fixed doses or levels in a blind fashion was appropriate in the absence of published data regarding this issue. The present study does not resolve this issue, as the ranges of doses and serum levels were probably too narrow to perceive a relationship. Finally, there were some baseline differences between the treatment groups in terms of age, dementia severity, and as-needed chloral hydrate use.

On the other hand, this was a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study conducted at four sites. The ratings were performed by blinded, experienced raters using valid and reliable tools assessing the key domains affected in dementia. Modern diagnostic criteria and an operational definition of agitation were used. Appropriate statistical analyses were performed on the basis of intent-to-treat principles. The number of subjects was relatively large for studies of this nature. The duration was sufficient to demonstrate near-term efficacy. None of the baseline differences was associated with differences between drug and placebo in efficacy or adverse effects. Chloral hydrate use was not associated with changes in efficacy or adverse effects, and use of chloral hydrate declined in the group receiving carbamazepine. Since the placebo group received minimal chloral hydrate at baseline, however, the significance of this change may be limited. On balance, these methodological attributes compare favorably with proposed standards for research of this nature (33).

Conclusions

The data strongly suggest that this form of therapy can be used effectively and safely for treatment of some demented patients with severe agitation, at least in the short term. These findings add to the growing literature regarding nonantipsychotic medications for this problem (8) and appear to support the widespread use of anticonvulsants by clinicians even in the absence of the type of data usually used to guide routine practice. The results would be expected to generalize to patients in other settings, as in preliminary studies of outpatients (20). The safety and efficacy of long-term use remain to be established. Since carbamazepine induces its own metabolism and has a high likelihood of drug-drug interactions, its use is associated with the risk of variable efficacy and toxicity of carbamazepine itself, as well as of drugs administered concurrently. For these reasons, we have begun exploring the efficacy and tolerability of other, potentially safer anticonvulsants (34).

|

|

|

|

Received Dec. 6, 1996; revision received June 9, 1997; accepted July 17, 1997. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, N.Y., and the Program in Neurobehavioral Therapeutics, Monroe Community Hospital. Address reprint requests to Dr. Tariot, Program in Neurobehavioral Therapeutics, Monroe Community Hospital, 435 East Henrietta Rd., Rochester, NY 14620. Supported by National Institute on Aging grants AG-10463 (to the Rochester Area Pepper Center) and AG-08665 (to the Rochester Alzheimer's Disease Care Center) and by Monroe Community Hospital. Carbamazepine and placebo were donated by CIBA-Geigy Corp., Summit, N.J. The authors thank Lon Schneider, M.D., for consultation; Adrian Leibovici, M.D., for assistance with enrollment; the Monroe Community Hospital Pharmacy and Laboratory; and the patients, families, and staff who made this study possible.

FIGURE 1. Total BPRS Scores at Week 0 and Week 6 for Nursing Home Patients With Agitation and Dementia in a Double-Blind Comparison of Placebo (N=24) and Carbamazepine (N=26)a

aThese data were used in the primary efficacy analysis.

FIGURE 2. Weekly Mean Total BPRS Scores for Nursing Home Patients With Agitation and Dementia in a Double-Blind Comparison of Placebo (N=24) and Carbamazepine (N=26)

1. Tariot PN, Mack JL, Patterson MB, Edland SD, Weiner MF, Fillenbaum G, Blazina L, Teri L, Rubin E, Mortimer JA, Stern Y, Behavioral Pathology Committee of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease: The Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1349–1357Link, Google Scholar

2. Cohen-Mansfield J: Agitated behaviors in the elderly, II: preliminary results in the cognitively deteriorated. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986; 34:722–727Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Reisberg B, Franssen E, Sclan SG: Stage specific incidence of potentially remediable behavioral symptoms in aging and Alzheimer's disease: a study of 120 patients using the BEHAVE-AD. Bull Clin Neuroscience 1989; 54:95–112Google Scholar

4. Cohen-Mansfield J, Billig N: Agitated behaviors in the elderly, I: a conceptual review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986; 34:711–721Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rovner BW, Kafonek S, Filipp L, Lucas MJ, Folstein MF: Prevalence of mental illness in a community nursing home. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1446–1449Link, Google Scholar

6. Marx MS, Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P: A profile of the aggressive nursing home resident. Behavior, Health, and Aging 1990; 1:65–73Google Scholar

7. Tariot PN, Podgorski CA, Blazina L, Leibovici A: Mental disorders in the nursing home: another perspective. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1063–1069Link, Google Scholar

8. Tariot PN, Schneider LS, Katz IR: Anticonvulsant and other non-neuroleptic treatment of agitation in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1995; 8(suppl 1):S28–S39Google Scholar

9. Burton LC, Rovner BW, German PS, Brant LJ, Clark RD: Neuroleptic use and behavioral disturbance in nursing homes: a 1-year study. Int Psychogeriatr 1995; 7:535–545Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schneider LS, Pollock VE, Lyness SA: A metaanalysis of controlled trials of neuroleptic treatment in dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990; 38:553–563Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Tariot PN, Erb R, Leibovici A, Podgorski CA, Cox C, Asnis J, Kolassa J, Irvine C: Carbamazepine treatment of agitation in nursing home patients with dementia: a preliminary study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42:1160–1166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lemke MR: Effect of carbamazepine on agitation in Alzheimer's inpatients refractory to neuroleptics. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:354–357Medline, Google Scholar

13. Chambers CA, Bain J, Rosbottom R, Ballinger BR, McLaren S: Carbamazepine in senile dementia and overactivity—a placebo controlled double blind trial. IRCS Med Sci 1982; 10:505–506Google Scholar

14. Overall JE, Gorham DR: Introduction: the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:97–98Google Scholar

15. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Tariot PN, Frederiksen K, Erb R, Leibovici A, Podgorski CA, Asnis J, Cox C: Lack of carbamazepine toxicity in frail nursing home patients: a controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995; 43:1026–1029Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Sultzer DL, Levin HS, Mahler ME, High WM, Cummings JL: A comparison of psychiatric symptoms in vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1806–1812Link, Google Scholar

18. Greenblatt DJ: Sedative-hypnotics: sleep disorders in the elderly, in Physicians' Handbook on Psychotherapeutic Drug Use in the Aged. Edited by Crook T, Cohen G. New Canaan, Conn, Mark Powley Assoc, 1981, pp 59–65Google Scholar

19. Frederiksen K, Tariot P, DeJonghe E: Minimum Data Set Plus (MDS+) scores compared with scores from five rating scales. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44:305–309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Gleason RP, Schneider LS: Carbamazepine treatment of agitation in Alzheimer's outpatients refractory to neuroleptics. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51:115–118Medline, Google Scholar

21. Rhoades HM, Overall JE: The semistructured BPRS interview and rating guide. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:101–104Medline, Google Scholar

22. Overall JE, Beller SA: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) in geropsychiatric research, I: factor structure on an inpatient unit. J Gerontol 1984; 39:187–193Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Aarsland D, Cummings JL, Yenner G, Miller B: Relationship of aggressive behavior to other neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:243–247Link, Google Scholar

24. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 217–222Google Scholar

25. Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, Endicott J, Williams D: The Overt Aggression Scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:35–39Link, Google Scholar

26. Lawton MP, Brody E: Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969; 9:179–186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Auer SR, Sclan SG, Yaffee RA, Reisberg B: The neglected half of Alzheimer disease: cognitive and functional concomitants of severe dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42:1266–1272Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Post RM, Weiss SRB, Chuang D-M: Mechanisms of action of anticonvulsants in affective disorders: comparisons with lithium. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12(Feb suppl 1):23S–35SGoogle Scholar

30. Maitre L, Baltzer V, Mondadoni C, Olpe HR, Baumann PA, Waldmeier PC: Psychopharmacological and behavioral effects of antiepileptic drugs in mood disorders, in Anticonvulsants in Affective Disorders. Edited by Emrich HM, Okuma T, Muller AA. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1984, pp 3–13Google Scholar

31. Elphick M, Anderson SMP, Hallis KF, Grahame-Smith DG: Effects of carbamazepine on 5-hydroxytryptamine function in rodents. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990; 100:49–53Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Rodgers RJ, Depaulis A: GABAergic influences on defensive fighting in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1982; 17:451–456Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Teri L, Lodgson RG: Methodologic issues regarding outcome measures for clinical drug trials of psychiatric complications in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1995; 8(suppl 1):S8–S17Google Scholar

34. Porsteinsson A, Tariot PN, Erb R, Gaile S: An open trial of valproate for agitation in geriatric neuropsychiatric disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar