Pretreatment Attrition in a Comparative Treatment Outcome Study on Panic Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Whereas the fact of attrition during the course of treatment is well documented, little is known about the factors that affect sample selection before the beginning of a study (“pretreatment attrition”). The present study reports on the degree and sources of pretreatment attrition at two sites of a multicenter study on panic disorder that compared treatment outcomes for imipramine and cognitive behavior therapy. METHOD: Data were collected at two clinical research sites, one with a pharmacological treatment orientation (N=420) and one with a psychosocial treatment orientation (N=208). RESULTS: The main source of pretreatment attrition was participant refusal. At both research sites, eligible patients most often refused participation because they were either unwilling to start treatment with imipramine (30.6% and 47.4%, respectively) or discontinue their current medication (22.6% and 35.1%, respectively). CONCLUSIONS: Results from comparative treatment outcome studies are limited not only to people who meet the study criteria but also to those who are willing to begin a medication treatment and discontinue their current medication. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:43–47)

Participant attrition is considered to be a significant threat to the external validity of any study that requires measurement at two or more points in time (1). Attrition may pose a serious threat to the external validity of a study if the groups show different dropout rates or if there is a significant treatment-by-attrition status interaction on pretest measures of the dependent variables (2, 3). Graham and Donaldson (4), however, suggested that even if there is differential attrition, the results are unbiased if the attrition mechanism is accessible (i.e., available for analysis).

Whereas attrition that occurs during the course of a study (e.g., dropouts) is reasonably well documented and studied (5–14), less is known about attrition that occurs before the beginning of a study (“pretreatment attrition”). The goal of the present study was to estimate the magnitude and to explore the causes of the participant attrition that occurs before study enrollment as a result of exclusion of subjects and participant refusals. The study took place within the context of a comparative treatment outcome study of panic disorder at two research sites with different treatment orientations (i.e., psychosocial versus pharmacological).

Preliminary data were gathered from 1,022 patients with panic disorder who were assessed at 1) the Phobia Clinic at Hillside Hospital, Long Island Jewish Medical Center, Glen Oaks, N.Y., and 2) the Phobia and Anxiety Disorders Clinic at the Center for Stress and Anxiety Disorders, Albany, N.Y. These two clinical research centers were part of a four-site outcome study that compared imipramine and psychosocial treatment of panic disorder. Although four sites participated in the multicenter study (the other two sites were the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh and the Anxiety Disorders Clinic at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.), data will be reported only from Hillside and Albany. The Center for Stress and Anxiety Disorders in Albany is well known for its psychosocial orientation, whereas Hillside Hospital is well known for its psychopharmacological approach. Both settings are established research and treatment centers. Hillside Hospital is located on the border of Long Island and Queens. The Center for Stress and Anxiety Disorders in Albany is located in upstate New York, approximately 200 miles away from Hillside. Both centers are located in metropolitan areas and are easily accessible by public transportation.

METHOD

Subject Selection

Patients from Albany and Hillside were referred by other health professionals or were self-referred. Hillside also actively recruited patients to participate in various research studies (e.g., through advertisements in local newspapers). Initially, 708 patients who met criteria for panic disorder were assessed at Hillside, and 314 panic disorder patients came to Albany between November 1992 and September 1995; these patients displayed the full range of agoraphobic severity. Since diagnostic criteria for the study specified that patients have no more than mild agoraphobia, 288 patients (40.7%) from Hillside and 106 patients (33.8%) from Albany who presented with moderate to severe agoraphobia were excluded from the study and will not be referred to again. Thus, the present report is based on data from 420 patients from Hillside and 208 patients from Albany.

All potential patients were screened over the telephone and, if eligible, were invited for a diagnostic assessment by experienced clinicians who used structured clinical interviews. The initial screening procedure and diagnostic assessment before study enrollment was not uniform across the two sites. Patients from Albany initially completed either the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule, Revised (15), or the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version (16). Patients from Hillside were initially interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (17) and the agoraphobia section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule, Revised. Although the two sites used different initial assessment and screening instruments, the same diagnostic criteria were used to determine eligibility for the study. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule and the SCID are both structured diagnostic interviews that were administered by experienced and trained clinicians. The initial diagnoses were then confirmed at both sites by using the same modified version of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule, Revised, which served as the final screen for the study. A rigorous quality control procedure ensured consistency of the diagnostic assessments within and across sites. If potential participants met DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria for panic disorder with no more than mild agoraphobia, they were invited to participate in the multicenter comparative treatment outcome study.

Men and women between the ages of 18 and 65 with the principal DSM-III-R diagnosis of panic disorder with mild agoraphobia were potentially eligible to participate in the study. Prestudy exclusion criteria included the following: 1) certain additional DSM-III-R lifetime diagnoses (e.g., bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorders such as schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or atypical psychosis); 2) current active suicidal potential; 3) current (or partially remitted) psychoactive substance dependence, psychoactive substance abuse, or a history of intravenous drug use; 4) organic mental disorders or mental retardation; 5) medical contraindications for imipramine treatment (clinically significant liver disease, history of clinically significant seizure disorder, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, history of hypersensitivity to tricyclic medication, pregnancy, lactation or planned pregnancy during the course of treatment, history of greater intraocular pressure or narrow angle glaucoma, presence of any contemporaneous medication treatment that could interfere or interact with tricyclic medications, current uncontrolled clinically significant thyroid disease or other significant endocrinopathy, or current chemotherapy or radiation treatment for cancer); 6) unsuccessful prior study treatments, either psychological (cognitive behavior treatment that focused on fear of sensations associated with panic or that used systematic exposure to somatic sensations associated with panic attacks) or pharmacological (minimum doses of imipramine [200 mg/day for 1 month] or equivalent tricyclic or heterocyclic antidepressant, phenelzine [75 mg/day] or equivalent monoamine oxidase inhibitor, or fluoxetine [20 mg/day], paroxetine [20 mg/day], sertraline [50 mg/day], or equivalent selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI]); 7) concurrent psychotherapeutic or pharmacological treatment for any psychiatric condition unless the patient was willing to discontinue it; and 8) application pending for a medical disability claim.

Invitation to Participate in Study

Eligible patients were informed about the study either immediately after the screening interview or at a later time by telephone. They were told that the goal of the study was to investigate the relative efficacy of a psychopharmacological treatment (imipramine) and a psychosocial intervention (panic control therapy [18]) for the treatment of panic disorder. Patients were also told that they would be randomly assigned to one of five treatment conditions: 1) imipramine alone, 2) panic control treatment alone, 3) placebo pill alone, 4) a combined treatment of imipramine and panic control treatment, and 5) a combined treatment of placebo pill and panic control treatment. Patients were informed that despite the use of a placebo pill, they would have a 92% chance of receiving an active treatment and that the treatment as well as physical examinations and diagnostic evaluations would be free of charge. Furthermore, patients were told that therapists and patients would be blind regarding placebo pill versus imipramine. Patients were also informed that they would need to discontinue any psychotropic medications before entering the study and that they could not be pregnant or nursing during the course of the study.

Unless the subject volunteered the information, the interviewer asked open-ended questions (e.g., “May I ask you why you decided not to participate?”). The advantage of this methodology over administering a questionnaire or a structured interview was that this procedure minimized interviewer and experimenter bias. However, the disadvantage of such an unstructured method was that some of the information was difficult to classify or even unclassifiable if patients did not provide any information.

RESULTS

As indicated in table 1, the two sites were comparable in the number of excluded subjects and the number of subjects who accepted but decided not to continue. However, at Hillside more eligible patients refused study participation (χ2=54.50, df=1, p<0.0001), and thus fewer patients participated (χ2=102.16, df=1, p<0.0001) than did at Albany (all chi-square values were calculated with continuity correction). These differences remained statistically significant after a Bonferroni correction (p<0.05/20=0.002).

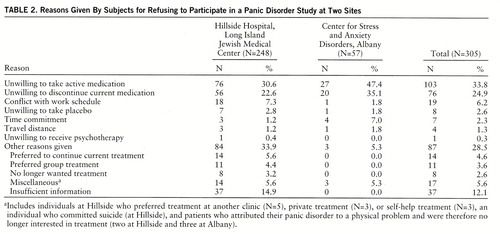

The reasons for subject refusals are listed in table 2. A substantial number of patients from both sites refused participation in the study because they were unwilling either to begin treatment with imipramine or discontinue their current medication. However, only a small number of patients refused to participate because of the possibility of being assigned to the placebo condition, and only one patient (at Hillside) refused because of an unwillingness to receive psychotherapy.

The statistical comparisons showed that patients from Albany tended to refuse participation more often than patients from Hillside because of an unwillingness to take active medication (χ2=5.07, df=1, p<0.03), discontinue their current medication (χ2=3.24, df=1, p<0.08), or make the time commitment (χ2=4.62, df=1, p<0.04). Furthermore, the information for determining the reasons for participant refusal tended to be more often insufficient at Hillside than at Albany (χ2=9.68, df=1, p<0.004). None of these differences, however, was statistically significant after a Bonferroni correction (p<0.05/20=0.002).

Information on the patients' medication status was available from all 20 Albany patients and 54 of the 56 Hillside patients who refused participation in the study because of an unwillingness to discontinue their current medication. The majority of these patients (70% at both sites) were taking benzodiazepines (14 at Albany and 38 at Hillside).

At Albany, 12 patients were taking alprazolam (mean dose=2.13 mg/day, range=0.20–10.00). The other benzodiazepines taken by those who refused the study were diazepam and lorazepam. Buspirone was the second most frequently reported medication (N=3, 15%). Other medications included barbiturates, β blockers, cyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, decongestants, narcotics, and other antianxiety agents (hydroxyzine) or antidepressants (trazodone). On average, patients who refused to discontinue their current medication were taking two different medications (mean=1.9; range=1–5).

Similar results were found in the group of patients from Hillside. Patients who refused to discontinue their current medication were most often taking alprazolam (38%, N=21). These patients were receiving an average of 1.88 mg/day (range=0.12–4.00). Other benzodiazepines taken included clonazepam, clorazepate dipotassium, diazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride, and clidinium bromide. Clonazepam was the second most frequently reported medication (N=10, 18%) among those who refused to discontinue their current medication. Other medications included barbiturates, β blockers, calcium channel blockers, cyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, phenothiazine, SSRIs, and other antianxiety agents (hydroxyzine and buspirone) or antidepressants (bupropion). On average, patients at Hillside who refused to discontinue their current medication were taking 1.6 (range=1–4) different medications.

DISCUSSION

Despite differences in the treatment orientation (as well as the location and the recruitment procedure), we found that pretreatment attrition due to exclusion of participants was comparable at the two research sites. Only a small percentage of potential participants at both sites were excluded because they did not meet the study criteria (18.3% of the total group). The most important source of pretreatment attrition was participant refusals (48.6% of the total group).

One might have expected relatively more refusals to take medications at Albany (the site with the psychosocial orientation) and more refusals to undergo psychosocial treatment at Hillside (the site with the pharmacological orientation). However, after we controlled for the experiment-wise error rate, the two sites did not differ in the reasons given for the refusals. Participants at both sites most often refused because they were unwilling to either begin treatment with imipramine or discontinue their current medication, which was most often a benzodiazepine (70% at both sites). Although the study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that included a placebo-only condition, very few people reported that they refused to participate in the study because they did not want to be assigned to the placebo condition (seven subjects from Hillside and one subject from Albany). The low rate of refusals due to the placebo condition might have been due to the low chance of receiving a placebo (8% versus 50% in most other studies). Furthermore, only one patient refused because of an unwillingness to be assigned to the psychotherapy only condition, whereas more than half of the subjects at each site declined participation because of the unwillingness to take medication or the requirement to stop taking current medications. This result suggests that our study group had in general a more positive bias toward psychotherapy than toward medication.

The total refusal rate at Hillside was greater (59.0% versus 27.4%) and the percentage of patients from the initial pool who entered into the study was lower (12.9% versus 50.5%) than the rates found at Albany. This might have been a result of differences in the subject recruitment procedure. Hillside actively recruited subjects with panic disorder for various free pharmacological treatment studies through advertisements, whereas at Albany free treatment was offered to patients who were part of the normal clinic flow, and subjects were not recruited through advertisements. Therefore, some of the patients from Hillside may have contacted the clinic with the expectation of receiving free treatment. In contrast, patients from Albany were unaware of this possibility and might have been pleasantly surprised about the option of receiving free treatment, which might have increased their likelihood to accept disposition to the study.

Although the data of the present study were based on a large number of subjects (N=1,022), only two of the four sites (the two with the most divergent treatment orientations) were included, which reduces the generalizability of the results. Greater weight could have been added to the major conclusion of this study if the data had been obtained from the entire study period, which lasted 5 years, and if the same pretreatment attrition results had been found at all four sites, without regard to their orientation. However, because of complications with retrieving the information retrospectively and missing data from some time periods and some sites, it was decided to limit the study to only two sites and a time period of 2 years and 11 months. This approach allowed us to gather sufficient information to conduct the present study.

It is uncertain if and to what extent pretreatment attrition has affected the external validity of the present study. In general, attrition does not affect the external validity if specific study characteristics (e.g., the type of treatment conditions) are unrelated to the sample selection. However, our data show that patients at both sites refused the study more often because of the study medication (in this case imipramine) than because of the psychosocial treatment, which suggests differential attrition during the pretreatment phase of our study. Future studies will need to evaluate the actual effects of differential pretreatment attrition on the external validity of comparative treatment outcome studies.

In summary, our data show that, independent from the treatment orientation of the research site, pretreatment attrition resulted in the exclusion of two types of patients—those who did not “believe in” medications (in this case imipramine) and those who were unable to discontinue their current medications (which was most often a benzodiazepine). Thus, our study indicates that the results from comparative treatment outcome studies are limited not only to people who meet the study criteria but also to those who are willing to begin medication treatment and discontinue their current medication.

Although further studies are needed to explore and identify the source of pretreatment attrition and its influence on study sample composition, we suspect that similar problems may apply to any treatment outcome study that compares psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. We recommend that the results of previous and future studies be critically evaluated on the basis of the source and the extent of pretreatment attrition. The following factors seem to be important to consider: 1) the subjects' treatment preference, 2) the information given to the subjects about the objectives of the study, 3) the exclusion and inclusion criteria of the study, and 4) the accessibility and affordability of therapy in other settings.

|

|

Presented in part at the 16th national conference of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America, Orlando, Fla., March 28–31, 1996. Received Dec. 19, 1996; revision received June 18, 1997; accepted July 3, 1997. From the Phobia Clinic, Hillside Hospital, Long Island Jewish Medical Center, Glen Oaks, N.Y.; the Anxiety Disorders Clinic, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh; the Anxiety Disorders Clinic, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.; and the Center for Stress and Anxiety Disorders, Albany, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hofmann, Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University, 648 Beacon St., 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215-2015. Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-45965 to Drs. Barlow, Gorman, Shear, and Woods and an NIMH Research Scientist Award to Dr. Gorman. The authors thank Marilyn Smith, A.C.S.W., for her assistance in the data collection and David H. Hershberger, B.A., and David A. Spiegel, M.D., for their editorial comments.

1. Hansen WB, Collins LM, Malotte CK, Johnson CA, Fielding JE: Attrition in prevention research. J Behav Med 1985; 8:261–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Little RJA, Rubin DB: Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1987Google Scholar

3. Little RJA, Rubin DB: The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociological Methods and Res 1989; 18:292–326Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Graham JW, Donaldson SI: Evaluating interventions with differential attrition: the importance of nonresponse mechanisms and use of follow-up data. J Appl Psychol 1993; 78:119–128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Biglan A, Hodd D, Brozovsky P, Ochs L, Ary D, Black C: Subject attrition in prevention research. NIDA Res Monogr 1991; 107:213–234Medline, Google Scholar

6. Farmer ME, Locke BZ, Liu IY, Moscicki EK: Depressive symptoms and attrition: the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Int J Methods in Psychiatr Res 1994; 4:19–27Google Scholar

7. Green SM, Navratil JL, Loeber R, Lahey BR: Potential dropouts in a longitudinal study: prevalence, stability, and associated characteristics. J Child and Family Studies 1994; 3:69–87Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Kazdin AE, Mazurick JL: Dropping out of child psychotherapy: distinguishing early and late dropouts over the course of treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:1069–1074Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Kelly T, Soloff PH, Cornelius J, George A, Lis JA, Ulrich R: Can we study (treat) borderline patients? attrition from research and open treatment. J Personality Disorders 1992; 6:417–433Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Longo DA, Lent RW, Brown SD: Social cognitive variables in the prediction of client motivation and attrition. J Counseling Psychol 1992; 39:447–452Crossref, Google Scholar

11.& Ouml;jehagen A, Berglund M: Acceptance, attrition, and outcome in an outpatient treatment programme for alcoholics. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 242:82–83Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Roffman R, Klepsch R, Wertz JS, Simpson EE, Stephens RS: Predictors of attrition from an outpatient marijuana-dependence counseling program. Addict Behav 1993; 18:553–566Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Snow DL, Tebes JK, Arthur MW: Panel attrition and external validity in adolescent substance use research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:804–807Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Winefield AH, Tiggeman M, Winefield HR: Attrition bias and internal validity in a longitudinal study of youth unemployment. Aust J Psychol 1991; 43:69–73Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Di Nardo PA, Barlow DH: Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule, Revised (ADIS-R). Albany, NY, Graywind Publications, 1988Google Scholar

16. Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH: Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L). San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1994Google Scholar

17. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1985Google Scholar

18. Barlow DH, Craske MG, Cerny JA, Klosko JS: Behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behavior Therapy 1989; 20:261–282Crossref, Google Scholar