Shifting to Outpatient Care? Mental Health Care Use and Cost Under Private Insurance

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Concern over rising health care costs has put pressure on providers to reduce costs, purportedly by reducing inpatient care and increasing outpatient care. METHOD: Inpatient and outpatient claims were analyzed for adult users of mental health services (180,000/year on average) from a national study group of 3.9 million privately insured individuals per year from 1993 to 1995. Costs and treatment days per patient were compared across diagnostic groups and stratified by whether patients were hospitalized. RESULTS: Inpatient mental health costs fell $2,507 (30.4%) over the period, driven primarily by decreases in hospital days per patient per year (19.9%), with smaller changes in the proportion of enrollees who received inpatient care (increase of 0.8%) and a decrease in per diem costs (9.1%). Outpatient mental health costs also declined over the period, falling 13.6% for patients also using inpatient services and 14.6% for patients receiving only outpatient care. Patients whose primary diagnosis was mild to moderate depression saw the largest decrease in inpatient cost per patient (42.8%); those diagnosed with schizophrenia experienced the smallest decrease (23.5%). For patients using outpatient services only, those diagnosed with substance abuse experienced the largest decrease in costs (23.5%); those diagnosed with schizophrenia experienced the smallest decrease (8.6%). CONCLUSIONS: Substantial cost reductions for mental health services are primarily a result of reductions in inpatient and outpatient treatment days. Declines in inpatient service use were not accompanied by increases in outpatient service use, even for severely ill patients requiring hospitalization. Managed care has not caused a shift in the pattern of care but an overall reduction of care.

Concern over rapidly increasing health care costs has led to the development of various cost-containment mechanisms, such as utilization review, case management, exclusive contracting arrangements with selected providers, and risk sharing (1–3). These mechanisms are often described as components of managed care, but they are not limited to what are traditionally considered managed care plans (e.g., health maintenance organizations, preferred provider organizations). A principle goal of these mechanisms is to reduce total health costs by substituting appropriate, but less costly, outpatient services for more expensive inpatient services (4). Little research exists, however, on 1) the magnitude of the inpatient and outpatient cost savings over time for mental health services, 2) the extent to which outpatient services are substituted for inpatient services for mental health care, 3) what components of cost are most responsible for the savings, and 4) whether cost savings differ by diagnostic group. A number of studies have examined the impact of cost reduction mechanisms on mental health care costs in the public insurance arena (3, 5–8), yet relatively few data have been examined from private insurance plans (4, 9–11), which, along with out-of-pocket spending, account for approximately 40% of mental health and substance abuse expenditures (12). This article examines patterns of inpatient and outpatient adult mental health care use among a group of privately insured individuals in 1993 and 1995.

Annual mental health care costs for a health plan can be thought of as having three components: 1) the number of covered individuals receiving care, 2) the cost per day of treatment, and 3) the total number of treatment days per patient per year. Decreases in any one or combination of these factors will result in lower per capita annual costs. Using insurance claims data, we examined each of these components of mental health care costs for both inpatient and outpatient service use to determine how cost reductions have been achieved. We further stratified the analysis by a severity indicator (inpatient hospitalization) and by diagnosis to identify subgroups that have been most affected by the observed changes.

METHOD

Source of Data

Data for this study came from MEDSTAT’s MarketScan® database, which compiles claims information from private health insurance plans of large employers. The data set contains claims information for employees, their dependents, and early retirees of companies who participate in the database. The database contains over 3.8 million covered individuals per year from 1993 to 1995. These claims data were collected from over 200 different insurance companies, including Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans and third-party administrators. Our study group consisted of all adult individuals in the database who had a claim for mental health services in the years under study.

The study group included in our data set was increasingly subject to managed care mechanisms during the period under study. The percentage of the study group that was enrolled in either a preferred provider organization or a point-of-service plan increased from 27.7% in 1993 to 32.2% in 1995. Because a significant proportion of the data describing plan characteristics is missing for 1993, we cannot report trends over time. However, of the traditional indemnity plans for which we have this information, 72% used either case management or utilization review to control costs, and over 86% required precertification for an inpatient admission. Thus, the health plans included in our database used a variety of managed care mechanisms to control costs.

Measures

From the claims data, we constructed variables describing the number of adults receiving any mental health services, the total number of inpatient and outpatient days per patient during the year, the primary diagnosis, and the total cost per year. We defined mental health diagnoses as ICD-9 codes between 290.00 and 312.99. We measured the cost associated with a claim as the actual amount paid, not the charges. Since providers rarely receive all of the fees they charge, the paid amount is a more accurate measure of cost. Paid amounts include patient payments (deductibles or copayments), payments made by the patient’s insurance plan, and any savings from coordination with other insurance providers (subrogation and Medicare savings). Costs were adjusted for inflation, with all amounts reported in 1993 dollars.

Mental health service use and cost. We calculated the following measures for inpatient mental health service users for each year: 1) the number of enrollees who received inpatient mental health services, 2) the number of hospital days per patient per year, 3) the cost per day of treatment, 4) the annual cost of inpatient mental health services per individual, and 5) the annual number of hospital days and cost for inpatient mental health services per enrollee. For each individual, the annual number of treatment days for each primary diagnosis was calculated by summing the length of stay for each inpatient service associated with that diagnosis during the year. Total mental health treatment days were determined by summing across all the different mental health diagnoses for each individual. Total costs for inpatient mental health services were calculated in a similar manner (13).

Outpatient mental health service use and cost were measured in a similar fashion. We calculated 1) the number of enrollees receiving any outpatient mental health services, 2) the number of outpatient visits per patient per year, 3) the cost per outpatient visit, 4) the annual outpatient cost per individual, and 5) the annual number of visits and cost for outpatient mental health care services per enrollee. As a measure of illness severity, we identified outpatient service users who also received inpatient mental health services during each calendar year.

Finally, total cost per mental health user was calculated by summing inpatient and outpatient cost per individual. This gives a summary measure of the cost of mental health care per patient over the course of treatment during the year.

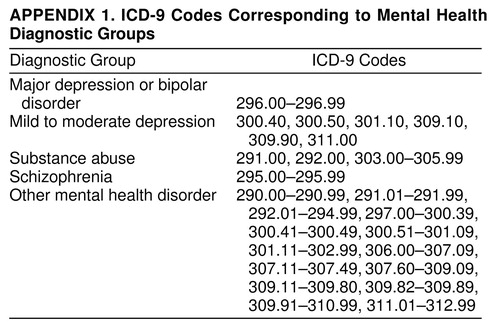

Diagnostic groups. The primary independent variables of interest were trends over time, the severity indicator, and mental health diagnosis. We defined five mental health diagnostic groups for both inpatient and outpatient users: 1) major depression or bipolar disorder, 2) mild to moderate depression, 3) substance abuse, 4) schizophrenia, and 5) other mental health disorder. The mild to moderate depression diagnostic group included any depression diagnoses not included in major depression or bipolar disorder. The ICD-9 codes that were included in each diagnostic group are described in Appendix 1. Each patient was assigned to a major diagnostic category for each year in which he or she received mental health services on the basis of the primary diagnosis in that year. The primary diagnosis was defined as the diagnosis responsible for the majority of mental health services during the year, as measured by the total paid amount. If a patient received both inpatient and outpatient services during the year, the primary diagnosis was defined as the diagnosis responsible for the majority of inpatient cost during the year. Of the diagnoses included in “other mental health disorder,” the most common were adjustment reaction (46.3%, ICD-9 codes 309.00 to 309.99) and neurotic disorders (31.2%, ICD-9 codes 300.00 to 300.99).

Other patient characteristics. Other independent variables of interest included patient demographic characteristics (age and gender) and two measures of illness severity: the number of different diagnoses in the year and whether the patient had a dual diagnosis. Patient age was grouped into three levels: age 18 to 44 years, 45 to 64 years, and 65 years and over. Individuals under the age of 18 years were not included in the study. The number of different diagnoses included all diagnoses, not just those for mental health. Finally, patients were defined as having a dual diagnosis if they had a primary or secondary diagnosis of substance abuse in the year in which they had a mental health diagnosis other than substance abuse.

Analysis

Data analysis proceeded in several steps. First, the proportion of claimants who used inpatient mental health services each year was determined. Average annual inpatient mental health cost and treatment days were analyzed for each year to determine how these variables changed during the 3 years studied and what components of cost were driving the change. We used analysis of covariance to compare average costs across years and calculated adjusted means for the annual number of treatment days and paid amounts, controlling for age, gender, diagnostic group, the number of different diagnoses, and whether the patient had a dual diagnosis.

Next, we performed the same analyses for outpatient mental health service users. We stratified the outpatient analysis by whether the individual also received inpatient mental health services to determine if trends in outpatient care were different for these patients.

Finally, we stratified the above analyses by primary diagnostic group to determine whether these populations were differentially affected by the change in treatment days and cost. We used t tests to determine whether differences within diagnostic groups over time were significant.

RESULTS

Study Group Characteristics

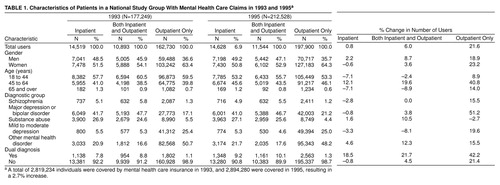

Table 1 reports characteristics for both inpatient and outpatient mental health users in our study group for 1993 and 1995. Of the enrollees who received inpatient mental health services, the majority also received outpatient services (75.0% in 1993). The majority of patients receiving only outpatient mental health services were female (63.4% in 1993), whereas inpatient users were more evenly divided across gender. A large majority of patients were under the age of 65 years, as one would expect of employees of large companies. The most common primary mental health diagnoses among inpatient users were major depression or bipolar disorder (41.7% in 1993), followed by substance abuse (26.9% in 1993), and other mental health disorder (20.9% in 1993). Among patients receiving only outpatient services, the most common primary diagnoses were other mental health disorder (50.7% in 1993), mild to moderate depression (25.4% in 1993), and major depression or bipolar disorder (17.1% in 1993). The proportion of patients who had dual diagnoses was higher among inpatient users than outpatient users (7.8% versus 1.1% in 1993), but for both groups, this proportion grew over time.

Trends for Use and Cost in Inpatient Care

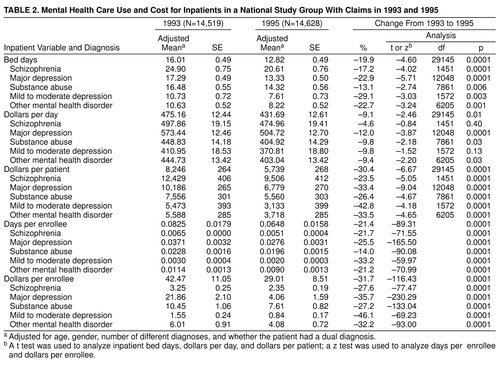

Table 2. reports results for inpatient service use and cost. Overall, cost per inpatient decreased $2,507 (30.4%) from 1993 to 1995. The decrease was driven primarily by a decrease in the number of bed days per patient, which fell 19.9% during the period. The cost per day of treatment fell 9.1% overall, while the number of inpatient users remained fairly constant (Table 1). Inpatients diagnosed with mild to moderate depression experienced the largest decline in cost per patient (42.8%), and inpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia experienced the smallest decline (23.5%). Declines in cost per patient were again driven by decreases in the number of bed days for all diagnostic groups. Cost per day of care decreased slightly for all diagnostic groups, but the decrease was significant for only three. The decreases in bed days and cost per patient were significant for all of the diagnostic groups. Because the distribution of users across diagnostic groups did not change substantially from 1993 to 1995, the annual number of bed days per enrollee and the annual cost per enrollee followed trends similar to those for the per-treated-patient measures.

Trends for Use and Cost in Outpatient Care

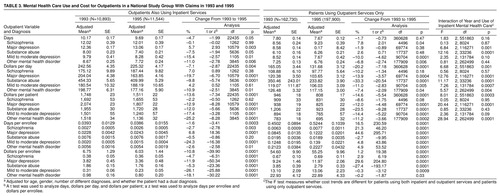

Outpatient care for inpatients.Table 3. shows trends in outpatient mental health service use and cost. The first set of columns shows outpatient service use and cost for patients who also received inpatient mental health services during the year, who are considered here to be more severely ill. The second set of columns reports outpatient service use and cost for patients who received only outpatient services. The last set of columns reports the significance of the interaction of year and use of inpatient mental health services. This statistic indicates whether the differences in outpatient service use and cost statistics among patients who also received inpatient services during the year and patients who received only outpatient care are significant over time.

For individuals who received both inpatient and outpatient services, overall outpatient cost per patient fell 13.6% between 1993 and 1995. Unlike inpatient cost reductions, the decrease in outpatient cost was more evenly divided between the decline in the cost per outpatient visit, which fell 7.1%, and a decline in the number of visits per year of 4.7%. Trends varied considerably by primary psychiatric diagnosis, however. Outpatient cost reductions were greatest for the less severe diagnoses of other mental health disorder and mild to moderate depression. The reductions over time, analyzed by t tests of means, were significant for all of the diagnostic groups except schizophrenia. For major depression and substance abuse, cost reductions were driven primarily by decreases in the number of outpatient visits. Declines in cost per patient for mild to moderate depression were mainly caused by a decrease in the cost per outpatient visit. The decrease in other mental health disorder outpatient cost per patient was fairly evenly split between declines in the number of visits and cost per visit.

The overall annual number of outpatient visits per enrollee and annual costs per enrollee show slightly smaller decreases over time than the per-treated-patient measures. This is because of a larger increase in the number of users in this group compared to the increase in the number of covered individuals over the period. The increase in the number of users was largest for patients diagnosed with substance abuse or other mental health disorder, whereas the number of patients diagnosed with mild to moderate depression decreased over the period. This led to smaller declines in visits and cost per enrollee for the substance abuse and other mental health disorder groups and larger declines in these measures for the mild to moderate depression group compared to the other diagnostic groups.

Outpatient services for outpatients. Among patients receiving only outpatient services, cost per patient also declined over the period at about the same rate observed among those who had been hospitalized. Overall, outpatient costs for these patients fell 14.6%, the cost per outpatient visit fell 20.2%, and the number of visits per year decreased 1.7%. Unlike patients who also used inpatient services, the proportion of enrollees receiving treatment increased 21.6%. For patients whose primary diagnosis was schizophrenia, major depression or bipolar disorder, or substance abuse, service use and cost followed the same pattern as overall outpatient cost: declines in the cost per outpatient visit were primarily responsible for decreases in the cost per outpatient. Patients diagnosed with mild to moderate depression or other mental health disorder also experienced declines in the cost per outpatient, but these declines were more evenly split between decreases in the number of outpatient visits per year and declines in the cost per visit. The decrease in cost per patient over time, analyzed by t tests of means, was significant for each of the diagnostic groups, but only marginally so for schizophrenia.

Because of the relatively large increase in the number of patients using only outpatient services, the overall annual number of visits and cost per enrollee increased over the period, despite decreases in these measures at the per-treated-patient level.

Finally, the last section of Table 3. shows F tests of the significance of the interaction of year and use of inpatient mental health services. The significance of this interaction term for overall outpatient cost per patient indicates that trends in service use and cost were different for these two groups of patients. Patients receiving only outpatient services had much larger decreases in the cost per visit (20.2% versus 7.1%) and smaller decreases in the number of visits per year (1.7% versus 4.7%). These trends did vary considerably by diagnosis, however.

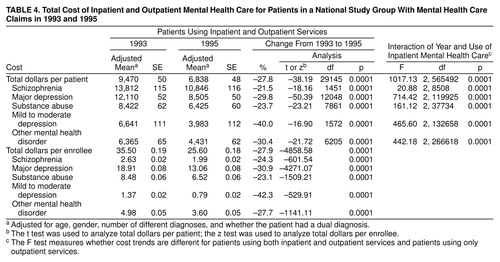

Total cost.Table 4. reports the total cost of mental health care for patients who received both inpatient and outpatient services during the year. The cost per patient fell over the period, but with the exception of substance abuse, the declines were much greater than for patients using only outpatient mental health services. The significance of the F tests of the interaction of year and use of inpatient mental health care in the last section confirms that patients receiving both inpatient and outpatient services and patients receiving only outpatient services experienced different trends in cost over the period.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used a national study group of privately insured adults to identify changing patterns of mental health care use and cost between 1993 and 1995. We found that inpatient cost per patient decreased over 30% during the period and that the decrease was primarily a result of a decline in the annual number of inpatient days per patient. Further, we found that cost reductions were greatest for patients diagnosed with mild to moderate depression and were smallest for those diagnosed with schizophrenia. Outpatient cost per patient also decreased during the period but much less than inpatient cost. Overall, cost per outpatient declined slightly more for patients who received only outpatient services compared to patients who also received inpatient care during the year, but there was considerable variation between mental health diagnostic groups. Total mental health treatment cost fell much more for inpatient mental health care users than for patients receiving only outpatient services. There is thus no evidence that inpatient cost reductions are accompanied by increases in outpatient expenditures.

As noted previously, a central goal of cost reduction mechanisms is to reduce cost by substituting appropriate, but less costly, outpatient services for more expensive inpatient services. However, our results suggest that declines in inpatient service use were not associated with increases in outpatient service use. Instead, both inpatient and outpatient service use and cost declined for people diagnosed with mental health disorders. It is possible that reductions in mental health service use and cost were offset by increases in general medical service use. However, an examination of medical care claims for the individuals in our study group did not show such an offset effect.

It is also possible that the observed declines in service use and cost over time can be explained by changes in treatment technologies, new therapy techniques, and the like. Although there have been new treatments for some disorders, such as the use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia, these new technologies are slow to be implemented and have been limited to certain disorders. The fact that we find similar patterns of decline in service use and cost across all of our diagnostic groups suggests that the implementation of new treatment technologies is not driving the changes.

There have been fears that managed care firms would reduce costs by restricting access to care for all enrollees, regardless of the severity of the illness. Although service use and cost do decrease for each diagnostic group, our results may mitigate these fears somewhat by showing that reductions in these measures are greatest for those groups that have the least severe diagnoses and are least costly to treat. Costs did not fall as much for those individuals in the more severe diagnostic categories, such as schizophrenia. However, individuals diagnosed with more severe illness are likely to exhaust their plan benefits much faster than people diagnosed with less severe illnesses; hence, a significant portion of their service use and cost may not be captured in the claims data.

Several limitations of this study require comment. First, since we do not have information on appropriateness of care, quality of treatment, treatment outcomes, or patient satisfaction, we cannot evaluate the effect of the cost reductions on these quality dimensions. Further research is needed to address this issue.

In addition, we do not have information on out-of-plan use. This can be important for two reasons. First, employees may be reluctant to submit a claim for mental health treatment for fear of being stigmatized and therefore may elect to receive care outside of their employer-sponsored health plans. Second, as noted above, health plans often limit the amount of care that is covered by the plan, and use above this limit may not be included in the claims data. It is possible that interstate variations in the availability of public sector services may have affected our results.

We did not examine changes in service mix within the broad areas of inpatient and outpatient care. Some of the declines in outpatient costs, for example, could be a result of moving from psychotherapy to medication management. However, because of the complexity of the claims data with respect to procedure codes, we left these issues for future research. Regardless of possible changes in service mix, we feel it is noteworthy that service use and cost have changed the way they did.

Despite these limitations, it is clear that both inpatient and outpatient mental health service use has declined drastically. This pattern is justified if we can find evidence that some care given in 1993 was unnecessary. In the absence of such evidence, these data generate concerns about the way in which health insurance plans control costs and access to care. Further studies are needed to determine the effect of these declines on clinical outcomes.

Received May 4, 1998; revisions received Sept. 24, 1998, and Jan. 28, 1999; accepted Feb. 10, 1999. From Connecticut-Massachusetts VA Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, West Haven, Conn.; and Northeast Program Evaluation Center, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Leslie, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, NEPEC/182, 950 Campbell Ave., West Haven, CT 06516; [email protected] (e-mail)

|

|

|

|

|

1. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, West JC: Peering into the “black box”: measuring outcomes of managed care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:870–877Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mechanic D, Schlesinger M, McAlpine DD: Management of mental health and substance abuse services: state of the art and early results. Milbank Q 1995; 73:19–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse services in Massachusetts. Psychatr Serv 1997; 48:1147–1152Google Scholar

4. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998; 17:40–52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Callahan JJ, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH, Larson MJ, Cavanaugh D: Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995; 14:173–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Beinecke RH, Shepard DS, Goodman M, Rivera M: Assessment of the Massachusetts Medicaid managed Behavioral Health Program: year three. Adm Policy Ment Health 1997; 24:205–220Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Dickey B, Normand SL, Norton EC, Azeni H, Fisher W, Altaffer F: Managing the care of schizophrenia: lessons from a 4-year Massachusetts Medicaid study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:945–952Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Busch S: Carving-out mental health benefits to Medicaid beneficiaries: a shift toward managed care. Adm Policy Ment Health 1997; 24:301–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Druss B, Bruce M, Jacobs S, Hoff R: Trends over a decade for an inpatient psychiatry service. Adm Policy Ment Health 1998; 25:427–435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: Changes in inpatient mental health utilization and cost in a privately insured population, 1993 to 1995. Med Care 1998; 37:457–468Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: Inpatient treatment of comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse disorders: a comparison of public sector and privately insured populations. Adm Policy Ment Health (in press)Google Scholar

12. Iglehart JK: Managed care and mental health. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:131–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Frank RG, Brookmeyer R: Managed mental health care and patterns of inpatient utilization for treatment of affective disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1995; 30:220–223Medline, Google Scholar