The Aurora Bridge

The Golden Gate Bridge has the unfortunate distinction of leading the nation in bridge suicides, with about 25 per year (1) . The George Washington Memorial Bridge in Seattle, known as the Aurora Bridge , is second on this unfortunate list. The first suicide occurred a month before the bridge was completed in 1932, when a shoe salesman jumped to his death. Since then, 230 people have killed themselves by jumping either into the ship canal, as in 80% of the cases, or into the heavily populated neighborhood below the bridge (2) . The drop is 155 ft at the peak and is fatal for 69%, with almost all survivors landing in the water (3) .

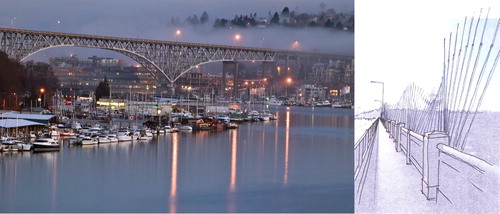

In response to pressure from the neighborhood below the bridge, six suicide prevention hotlines were installed in 2006. Callers may be connected to the Crisis Clinic or a 911 operator. Over the first 4 months, the Crisis Clinic received five calls from the new phones. During that time six people died by jumping off the bridge, two more than the yearly average (4) . In 2007, Washington Governor Christine Gregoire announced funding for an 8-ft suicide barrier, with construction to begin in summer 2009 and finish the following spring (5) . A total of $4.3 million will be allocated to create a barrier that meets a variety of design requirements. Structurally, it must be independent of the existing outer railing, attach to the bridge deck, and be capable of withstanding the weight of anyone who attempts to climb it. The conceptual design process included community members to develop ideas that reflect local values and the historic character of the bridge. One popular design from the Community Conceptual Design Report is pictured above on the right. It contains undulating rods that blur and fade from the vision of passing motorists to reveal views of the city skyline and surrounding mountains. Words or phrases from community members will be etched into some of the rods, e.g., “You are extraordinary,” “Someone special lives inside you,” and “Your talents are special.”

Other community members objected to a barrier and questioned whether suicidal people would substitute a different bridge or method. Such objections have impeded efforts to place barriers on the Golden Gate Bridge (1) . Suicide barriers have been installed in Washington, D.C. (6) , Augusta, Me. (7) , and Bern, Germany (8) , and have been effective in decreasing jumping from the secured structure without increasing suicide attempts from nearby bridges. It is more difficult to demonstrate that other means of suicide will not be substituted. A follow-up study on people rescued from the Golden Gate Bridge (9) and Swiss epidemiological studies (10) suggest that other means will not be substituted. As for the danger to densely populated areas below, barriers installed on the Eiffel Tower, the Empire State Building (11) , and the Space Needle in Seattle (2) have been effective.

1. Moran M: Suicide barrier sought for Golden Gate Bridge. Psychiatr News, April 1, 2005, p 21Google Scholar

2. Mudede C: Jumpers take it to the bridge. The Stranger (Seattle), April 13–19, 2000Google Scholar

3. Fortner GS, Oreskovich MR, Copass MK, Carrico CJ: The effects of prehospital trauma care on survival from a 50-meter fall. J Trauma 1983; 23:976–981Google Scholar

4. Gilmore S: Combined effort aims to stop suicides off Aurora Bridge. Seattle Times, May 18, 2007Google Scholar

5. Blankinship DG: Money for fence to cut Aurora Bridge suicides. Seattle Times, Dec 19, 2007Google Scholar

6. O’Carroll PW, Silverman MM: Community suicide prevention: the effectiveness of bridge barriers. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1994; 24:89–91; discussion 91–99Google Scholar

7. Pelletier AR: Preventing suicide by jumping: the effect of a bridge safety fence. Inj Prev 2007; 13:57–59Google Scholar

8. Reisch T, Michel K: Securing a suicide hot spot: effects of a safety net at the Bern Muenster Terrace. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2005; 35:460–467Google Scholar

9. Seiden RH: Where are they now? a follow-up study of suicide attempters from the Golden Gate Bridge. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1978; 8:203–216Google Scholar

10. Reisch T, Schuster U, Michel K: Suicide by jumping and accessibility of bridges: results from a national survey in Switzerland. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2007; 37:681–687Google Scholar

11. Friend T: Jumpers: the fatal grandeur of the Golden Gate Bridge. The New Yorker, Oct 13, 2003Google Scholar