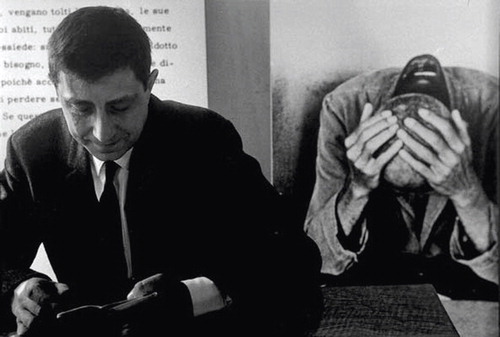

Franco Basaglia, 1924–1980

Italy enacted Law 180 (“Basaglia’s Law”) on May 13, 1978, and thereby initiated the gradual dismantling of its mental asylums. Franco Basaglia remains a controversial and historical figure in Italian psychiatry. Extolled as one of the most important innovations in psychiatry over the past 50 years or despised as hotly ideological and not sufficiently detailed in terms of services and provisions for alternatives to mental hospitals, Law 180 has survived several attempts to amend it and remains the principle of Italian mental health services (1) . The law states that dangerousness is no longer the basic criterion for commitment, commitment is restricted to therapeutic emergencies, compulsory admission must be to a general hospital unit, and mental hospitals are officially abolished (2 , 3) .

After receiving his degree in medicine from the University of Padua in 1949, Basaglia developed an interest in the study of phenomenological philosophers, such as Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Husserl, and Heidegger, and then he analyzed the work of historical and sociological critics of psychiatric institutions, such as Foucault and Goffman. He married Franca Ongaro, who closely worked with him to change the asylums and later entered the Italian parliament. After some years of clinical practice at the University of Padua, in 1961 he left the academic environment and went to head the asylum in Gorizia, with the idea of radically changing the old-fashioned institutional setting. He then moved to Parma (1969) and Trieste (1973). In January 1977, he announced the closure of the asylum in Trieste in favor of a new therapeutic community model that would allow persons with psychiatric disabilities to play a valuable role in society. Basaglia was a charismatic, innovative leader in Italian psychiatry, a discipline that was for many years poorly developed and confined to the gloomy atmosphere of mental hospitals; his contribution was essential to give visibility to psychiatry and move psychiatric practice into the realm of health care.

Basaglia died in 1980, only 2 years after the enactment of his law, and therefore he never saw the full positive and negative effects of its implementation.

1. Piccinelli M, Politi P, Barale F: Focus on psychiatry in Italy. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 181:538–544Google Scholar

2. de Girolamo G, Bassi M, Neri G, Ruggeri M, Santone G, Picardi A: The current state of mental health care in Italy: problems, perspectives and lessons to learn. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007; 257:83–91Google Scholar

3. Tansella M, Williams P: The Italian experience and its implications. Psychol Med 1987; 17:283–289Google Scholar