Asperger’s Syndrome: Diagnosis and Treatment

“Marc” is a 15-year-old male who presents with his parents for evaluation because of significant symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood. Marc responds verbally when greeted in the waiting room but avoids eye contact. He has an above-average IQ, with significantly higher verbal than nonverbal abilities. Academic difficulties in elementary school led to a diagnosis at age 8 of nonverbal learning disability. Marc continues to struggle academically and is falling further and further behind in school. He has strong interests in the Titanic and baseball that involve recitation of facts, dates, and numbers. He will talk at length on these topics, often using language that is more formal than expected for his age, but he is unable to sustain conversations on other topics. Although Marc prefers to interact with adults, he does describe himself as having friends; later his parents reveal that he does not interact with peers outside of school, and when asked, Marc is unable to describe what it means to be a friend. Marc’s parents are very concerned about the widening gap between Marc’s social development and that of his peers. Marc’s history includes perinatal problems, and his family history includes autism spectrum disorder.

Asperger’s syndrome (AS) is considered to be a variant of autism rather than a distinct disorder, similar if not equivalent to high-functioning autism. The condition was first recognized and labeled “autistic psychopathy” by Asperger in 1944 (1) . Asperger’s most famous cases were patients described as having above-average intellectual and language abilities, with significant disturbances in social and affective communication. However, Asperger also described cases of patients with low intellectual and language abilities, similar to those Kanner (2) described as autistic in 1943. The similarities Asperger noted among these individuals with widely varying intellectual and language abilities presaged the current notion of a “spectrum” of autistic disorders (3) . Asperger’s contribution to the field went beyond merely identifying and describing this condition; he was concerned that affected children would be misunderstood and maltreated, so he sought to increase awareness of autism. He also advocated an approach to education that involved individualized attention, an emphasis on strengths rather than weaknesses, and engagement in learning by tapping into the child’s special interests. These approaches continue to be used today in the education of children with AS.

Diagnosis

Although Asperger first described cases in 1944, the term “Asperger’s syndrome” as a diagnostic label did not come into use until several decades later when Wing (4) argued that autism included not only children who were aloof but also those who were socially active but odd in their behavior. Wing proposed a spectrum of disorders with varying degrees of severity in each of the three symptom domains that together comprise the diagnostic criteria for autism, namely, impairment in social interaction, impairment in communication, and restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of interests and behaviors. At about the same time that AS became a widely used descriptive label, the term “high-functioning autism” was also being used to refer to children with autism who were relatively more able, in either verbal or nonverbal intelligence (5) . Clinically, these two labels are sometimes used interchangeably, often describing children with autism who are atypical in their presentation and who frequently initiate social interactions (albeit lacking in reciprocity) as opposed to those who are more avoidant or aloof.

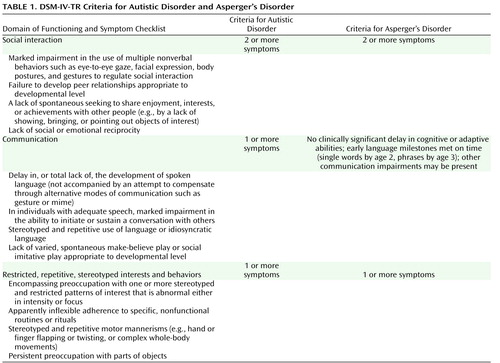

DSM-IV-TR provides criteria for a differential diagnosis of AS based on intact cognitive ability (absence of mental retardation or intellectual disability), no delays in early language milestones (i.e., use of single words by age 2 and phrases by age 3; see Table 1 ). However, this does not imply that language acquisition in AS is normal; for example, there may be deficits in pragmatic (i.e., social use of) language or use of overly formal or repetitive language. Hence, this distinction remains problematic. Results of research that has attempted to support a distinction between AS and high-functioning autism have thus far been mixed. The following section presents a brief review of this research (see also reference 6 ).

Asperger’s Syndrome vs. High-Functioning Autism

Over the past two decades, a growing body of research has attempted to address the diagnostic and phenotypic ambiguity between AS and high-functioning autism. Some authors believe that the neuropsychological and behavioral profiles of AS and high-functioning autism differ (e.g., reference 7 ), while others have argued that there is little empirical evidence for a distinction between these two disorders (e.g., references 8 , 9) . Ozonoff and colleagues (10) conducted a comprehensive study that examined differences based on external criteria (cognitive/intellectual profiles, executive function, language, current symptoms, early history, and course of illness) as opposed to criteria involving the definition of the two syndromes. They found few group differences in current symptom presentation and cognitive function but many differences in early history. Individuals with AS outperformed those with high-functioning autism on the comprehension subtest of the WISC-III and in expressive language ability, but there were no differences on measures of executive function (flexibility and planning). Individuals with AS also had better imaginative and creative abilities and more circumscribed interests, whereas those with high-functioning autism showed a greater insistence on sameness. Early history variables were best able to differentiate the two disorders. Compared with children with AS, those with high-functioning autism were more impaired in early language development and behavior over the preschool period, had more severe lifetime symptoms, and had a greater need for specialized education services. Ozonoff et al. concluded that AS and high-functioning autism appear to be on the same spectrum but differ primarily in severity of developmental course. However, in terms of prognosis, the preschool-age differences they identified had largely disappeared by adolescence, indicating that the prognosis for individuals with high-functioning autism may be better than previous studies have reported.

A more recent study (11) examined the core symptom domain of social interaction and used the Wing and Gould (12) classification system (aloof, passive, and active but odd) to evaluate potential differences in quality of social interaction between individuals with AS and those with autism. Results showed that individuals with AS tended to be active but odd in presentation as compared with the more aloof and passive profile of those with autism, supporting the view that these two groups may differ both in symptom severity (i.e., quantitatively) and in the quality of their social impairment.

There continues to be much debate regarding the overlap and differentiation of these two disorders. It is fueled in part by a tautological dilemma wherein the disorders are defined on the basis of severity of impairment, so studies that appear to confirm differences relating to severity of impairment are to be expected. More systematic studies of both quantitative and qualitative aspects of functioning are needed.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Current estimates indicate that AS occurs at a rate of about 2.5/10,000, as compared to 60/10,000 for all autism spectrum disorders (that is, autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, and AS). These rates represent an upward trend over time, due at least in part to changes in case definition and improved awareness (13) . The rates for AS have not been well established because of the paucity of research with carefully diagnosed samples. Likewise, relatively few studies of genetic and environmental factors in the pathophysiology of AS have involved large and well-characterized samples. One such study examined in detail the family, prenatal, and perinatal histories of 100 male children with AS who were followed into late adolescent and early adulthood (14) . Results indicated a paternal family history of autism spectrum disorder in about 50% of the sample, and pre- and perinatal risk factors in about 25% of cases. Pre- and perinatal factors included prenatal exposure to alcohol, severe postnatal asphyxia, neonatal seizures, and prematurity.

Even fewer studies have examined risk factors by diagnostic subgroup. One such study examined obstetric risk factors and found fewer pregnancy and labor complications in patients with AS than in those with autism, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, and comparison subjects; those with AS were more likely to have a forceps or vacuum delivery than those with autism, but they did not differ from comparison subjects on a number of other pre- and perinatal variables (15) .

Most studies of pre- and perinatal risk factors conclude that these factors do not operate independently in autism but may be related to extant fetal abnormalities or to genetic or environmental factors. This has led many researchers to speculate whether children with similar genetic risk factors vary in phenotypic expression (i.e., symptom severity) due to exposure to different levels of environmental risk. Regarding genetic factors, a genome-wide scan for susceptibility loci was performed on a sample of individuals with AS, identifying two loci (on chromosomes 1 and 3) that have similarly been implicated in the genetics of autistic disorder (16) . Studies such as these support the prevailing view that AS is not a separate disorder from autism but a variant on the milder end of the spectrum (5) .

Evidence-Based Assessment

In spite of the continuing debate regarding diagnostic issues, an evidence-based, best-practice assessment approach for autism spectrum disorders, including AS, includes a core diagnostic assessment as well as additional assessment for treatment planning, as described below. The instruments mentioned here are tools only and should not be used, in and of themselves, to make a diagnosis (17) .

Core Diagnostic Assessment

A comprehensive assessment for AS should include, at minimum, a detailed developmental history and review of social, communication, and behavioral development. Most centers use a tool such as the Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised (18 , 19) for this purpose. Direct observation of the patient, using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (20 , 21) , is also essential to gather the kind of information (i.e., observations of social behavior) necessary for a diagnosis. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule is a semistructured interview that requires established reliability and therefore is often conducted by practitioners specifically trained in autism spectrum disorders. Diagnostic tools specific to AS have been developed, but in general they have not been standardized with participants with confirmed diagnoses of AS, and psychometric properties have not been well studied. These include the Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (22) , the Gilliam Asperger Disorder Scale (23) , the Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (24) , and the Adult Asperger Assessment (25) .

Additional Assessment for Treatment Planning

A comprehensive evaluation should also include screening for medical and psychiatric issues, including seizures, sleep difficulties, significant sensory issues disrupting daily function, anxiety and depression, and other psychiatric and behavioral issues. In addition, a review of school records and previous testing and interventions, as well as consultation with the child’s teachers for their observations, particularly of peer interactions, is important to inform diagnosis and treatment planning. Assessment of intellectual, language, adaptive, and neuropsychological functioning may be conducted to further inform educational planning and treatment. Finally, an occupational therapy evaluation, with assessment of strategies to mitigate sensory issues, may be warranted, along with assessment of the family system (e.g., stress, depression, access to community resources), to improve outcomes for children with AS (26) .

Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders

The most common comorbid diagnosis in individuals with AS and high-functioning autism is depression, occurring in as many as 41% of patients (27) . Other psychiatric disorders or symptoms that have been reported include anxiety (8%), bipolar disorder (9%), schizophrenia (9%), attempted suicide (7%), hallucinations (6%), mania (5%), psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (3%), schizoid personality disorder (3%), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (1%). To compare these rates to those in children with autism, in a recent study of 109 children with autism (28), the most prevalent diagnoses were specific phobia (44%), OCD (37%), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (31%), and depression (10%). The relatively high rate of ADHD in Leyfer and colleagues’ sample (28) is of interest in light of the fact that the current DSM specifically excludes comorbidity with autism. Whether such a trumping rule is appropriate is the subject of current debate. Care must be taken when diagnosing certain other disorders, such as schizophrenia and psychosis, because the intense preoccupations and interests seen in individuals with AS can resemble delusions and disorders of thinking (29) . In these cases, a detailed history must be obtained to determine the presence of such idiosyncratic interests prior to the onset of a presumed psychosis. It could also be argued that personality traits, for example schizoid or obsessive-compulsive, are much more common than currently reported in individuals with high-functioning autism or AS and that the differential diagnosis in this domain is potentially very complicated.

Treatment

The average age at diagnosis of AS is about 11 years, compared with 5.5 years for autism (30) . This is problematic, as prognosis is related not only to cognitive and language abilities but also to the provision of early, appropriate, structured education programs (31) and interventions aimed at improving social competence (32 , 33) . A limited number of studies have examined the efficacy of treatment approaches specific to AS or high-functioning autism. No single methodology or intervention strategy has been identified as the most effective or shown to be successful for all participants, nor is there a single comprehensive treatment program for individuals with these disorders. Common approaches to treatment include adult-directed behavioral programs, such as those using principles of applied behavior analysis, naturalistic child-centered approaches, or a combination approach drawing on behavioral, developmental, and social-pragmatic principles (34) . The National Research Council and the Committee on Educational Interventions for Children With Autism have identified critical variables for treatment planning, including prioritizing goals based on core challenges in social communication, establishing proactive approaches to problem behaviors, individualizing modes of instruction, implementing supports across contexts, planning for transitions, addressing psychiatric comorbidity, and providing family support and education (35) .

Interventions to Improve Social Competence

A primary focus of most intervention programs for individuals with AS is on enhancing social competence; here we describe both general and newer, targeted approaches.

Social skills are typically taught using a variety of methods and in different settings, such as friendship groups at school, classroom activities, privately taught social skills group therapy programs, buddy or mentoring programs, and through individual and dyadic (i.e., pairing the child with AS with a peer) therapy. Methods or strategies for teaching social skills include direct instruction, role playing, modeling, social stories, in vivo practice with peers, and constructive feedback. The social stories technique refers to stories that can be written and illustrated to fit any scenario, with the goal of providing information on what people in a given situation are doing, thinking, and feeling. Social stories indicate the sequence of events, identify significant social cues and their meaning, and script for the child what he or she should do or say. Social stories are especially helpful in new situations, which often cause anxiety because they are unknown and unpredictable, but they are useful in any situation to enhance the child’s understanding of what is likely to occur and to explain what is expected of the child. The perspective of all participants in a given social story is carefully delineated, as theory of mind skills (i.e., the ability to take another’s point of view) are often impaired in people with AS and must be directly taught (36) .

Other general techniques for teaching social skills include first breaking skills down into smaller subskills and then teaching each skill through modeling and role plays. For example, conversation skills can be broken down into a number of subskills, such as greeting others, initiating topics, staying on topic, maintaining reciprocity, using nonverbal communication (eye contact, facial expressions, gestures) appropriately, checking in to see if the listener is still interested, and appropriately ending conversations (i.e., saying goodbye). Higher-level skills can include accepting suggestions, handling criticism, resolving conflicts, and showing empathy. Understanding the child’s cognitive profile is essential in tailoring a social skills program to an individual child’s needs and strengths. For example, verbal strategies should be utilized with children with better-developed verbal abilities, while visual strategies (e.g., social stories) should be emphasized with children with higher visual problem-solving skills.

Targeted Intervention Strategies

In recent years, a number of intervention studies have focused on teaching discrete aspects of social competence, such as joint attention, emotion recognition, and theory of mind abilities. In general, these studies have indicated positive results, but they have been limited by small sample sizes (many are best characterized as pilot studies) and lack of long-term follow-up. Nevertheless, they point to the utility of focused and individualized treatment strategies to augment more broad-based educational and social skills interventions for children with autism and AS. In a training study of theory of mind and executive function, Fisher and Happé (37) found that in a relatively short period (i.e., 5–10 days of training), children with autism spectrum disorders could improve their performance on theory of mind tasks but not on executive function tasks. In a study that examined the use of assistive technology to teach emotion recognition to students with AS, LaCava and colleagues (38) found improved performance not only on basic and complex emotions that were directly taught via a computer software program but also on complex voice emotion recognition for emotions not specifically included in the training software. Finally, Turner-Brown and colleagues (39) demonstrated the utility of a group-based cognitive behavioral intervention to teach theory of mind and other social communication skills to adults with high-functioning autism.

In sum, a comprehensive treatment plan for a child or adolescent with AS should capitalize on strengths, target specific areas of impairment (social, academic, adaptive) as well as comorbid medical or psychiatric disorders, and be implemented across settings to ensure success and generalization of skills. Additionally, there is emerging evidence to support the use of interventions targeting discrete aspects of social functioning to augment more broad-based intervention approaches.

Summary and Recommendations

AS, although first identified in 1944, is a relatively new diagnostic label referring to a set of behavioral characteristics shared by children with autism. Children and adults with AS typically have higher intellectual and linguistic abilities than those with autism but are quite impaired in their social communication skills. Individuals with AS are also at higher risk for certain psychiatric and medical disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and seizures. Diagnosing AS can be tricky, as the diagnostic criteria are not clearly differentiated from those defining autistic disorder. The prevailing view in the literature is that AS is not a distinct disorder but a milder variant of autism. Whether or not this is so, children with AS are typically diagnosed at much older ages than those with autism, and thus appropriate and targeted interventions are often not initiated at early ages, when they may have the greatest impact. Nevertheless, a number of strategies, including those promoting social competence, are widely used with children with AS and have been shown to have a positive impact on outcomes. Pharmacotherapy for associated conditions in AS has not been systematically studied and is currently informed by research in the general population.

After careful review of developmental history, school records, and past medical records as well as time spent directly observing and interacting with Marc, he was diagnosed as having Asperger’s syndrome, anxiety disorder not otherwise specified, and depression not otherwise specified. Marc’s anxiety was determined to be related to both school and social interactions. His depression, which did not meet full criteria, was based on a history of social failure and rejection and his report of lessened interest in and activities related to his areas of intense focus (e.g., he reported that baseball was less enjoyable). Recommended interventions included working with an autism specialist, privately or through the school district, who could advocate for Marc and his parents to ensure that he received additional specialized education services and accommodations to address his academic difficulties. For Marc’s anxiety and depression, treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor as well as individual psychotherapy was recommended. Since individuals with AS, even those who are highly verbal, tend to respond best to behavioral strategies, a concrete, skills-based approach to psychotherapy was recommended rather than a primarily cognitive approach. Targeted social skills interventions to promote prosocial skills and expand Marc’s peer group were recommended for implementation once his anxiety and depression improved. Finally, a recommendation for private speech and language therapy to address pragmatic deficits as well as social skills deficits was made. Marc’s parents were directed to state and local resources and support groups. The diagnosis was discussed with Marc directly, and he was given a list of excellent web sites that provide both information and community for adolescents and adults with AS.

1. Asperger H: Die “autistischen Psychopathen” im Kindesalter. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 1944; 117:76–136 [translated by Frith U, “Autistic psychopathy” in childhood, in Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Edited by Frith U. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp 36–92]Google Scholar

2. Kanner L: Autistic disturbances of affective content. Nerv Child 1943; 2:217–250Google Scholar

3. Wing L: Past and future research on Asperger syndrome, in Asperger Syndrome. Edited by Klin A, Volkmar F, Sparrow S. New York, Guilford, 2000, pp 418–432Google Scholar

4. Wing L: Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account. Psychol Med 1981; 11:115–129Google Scholar

5. Frith U: Emanuel Miller lecture: confusions and controversies about Asperger syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004; 45: 672–686Google Scholar

6. Reitzel J, Szatmari P: Learning difficulties in Asperger syndrome, in Asperger Syndrome: Behavioral and Educational Aspects. Edited by Prior M. New York, Guilford, 2003, pp 35–54Google Scholar

7. Klin A, Volkmar FR, Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Rourke BP: Validity and neuropsychological characterization of Asperger syndrome: convergence with nonverbal learning disabilities syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:1127–1140Google Scholar

8. Schopler E: Are autism and Asperger syndrome different labels or different disabilities? J Autism Dev Disord 1996; 26:109–110Google Scholar

9. Schopler E: Premature popularization of Asperger syndrome, in Asperger Syndrome or High-Functioning Autism? Edited by Schopler E, Mesibov GB, Kunce LJ. New York, Plenum, 1998, pp 385–399Google Scholar

10. Ozonoff S, South M, Miller JN: DSM-IV-defined Asperger syndrome: cognitive, behavioral, and early history differentiation from high-functioning autism. Autism 2000; 4:29–46Google Scholar

11. Ghaziuddin M: Defining the behavioral phenotype of Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 2008; 38:138–142Google Scholar

12. Wing L, Gould J: Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children: epidemiology and classification. J Autism Dev Disord 1979; 9:11–29Google Scholar

13. Fombonne E: Epidemiological surveys of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders: an update. J Autism Dev Disord 2003; 33:365–382Google Scholar

14. Gillberg C, Cederlund M: Asperger syndrome: familial and pre- and perinatal factors. J Autism Dev Disord 2005; 35:159–166Google Scholar

15. Glasson EJ, Bower C, Petterson B, de Klerk N, Chaney G, Hallmayer JF: Perinatal factors and the development of autism: a population study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:618–627Google Scholar

16. Ylisaukko-oja T, Nieminen-von Wendt T, Kempas E, Sarenius S, Varilo T, von Wendt L, Peltonen L, Järvelä I: Genome-wide scan for loci of Asperger syndrome. Mol Psychiatry 2004; 9:161–168Google Scholar

17. Ozonoff S, Goodlin-Jones BL, Solomon M: Evidence-based assessment of autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 34:523–540Google Scholar

18. Lord C, Rutter M, LeCouteur A: Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 1994; 24:659–685Google Scholar

19. Rutter M, LeCouteur A, Lord C: Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised Manual. Los Angeles, Western Psychological Services, 2003Google Scholar

20. Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Pickles A, Rutter M: The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2000; 30:205–223Google Scholar

21. Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule Manual. Los Angeles, Western Psychological Services, 2002Google Scholar

22. Ehlers S, Gillberg C, Wing L: A screening questionnaire for Asperger syndrome and other high-functioning autism spectrum disorders in school age children. J Autism Dev Disord 1999; 29:129–141Google Scholar

23. Gilliam JE: Gilliam Asperger Disorder Scale. Austin, Tex, PRO-ED, 2001Google Scholar

24. Myles BS, Bock SJ, Simpson R: Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale. Austin, Tex, PRO-ED, 2001Google Scholar

25. Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Robinson J, Woodbury-Smith M: The Adult Asperger Assessment (AAA): a diagnostic method. J Autism Dev Disord 2005; 35:807–819Google Scholar

26. Hauser-Kram P, Warfield ME, Shonkoff JP, Krauss MW: Children with disabilities: a longitudinal study of child development and parent well-being. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2001; 66:1–131Google Scholar

27. Howlin P: Outcome in adult life for more able individuals with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism 2000; 4:63–83Google Scholar

28. Leyfer OT, Folstein SE, Bacalman S, Davis NO, Dinh E, Morgan J, Tager-Flusberg H, Lainhart JE: Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: interview development and rates of disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2006; 36:849–861Google Scholar

29. Ghaziuddin M: Asperger syndrome: associated psychiatric and medical conditions. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 2002; 17:138–144Google Scholar

30. Howlin P, Asgharian A: The diagnosis of autism and Asperger syndrome: findings from a survey of 770 families. Dev Med Child Neurol 1999; 41:834–839Google Scholar

31. Kunce LJ, Mesibov GB: Educational approaches to high functioning autism and Asperger syndrome, in Asperger Syndrome or High-Functioning Autism? Edited by Schopler E, Mesibov GB, Kunce LJ. New York, Plenum, 1998, pp 227–262Google Scholar

32. Mesibov GB: Treatment issues with high-functioning adolescents and adults with autism, in High Functioning Individuals with Autism. Edited by Schopler E, Mesibov GB. New York, Plenum, 1992, pp 143–156Google Scholar

33. Howlin P, Yates P: The potential effectiveness of social skills groups for adults with autism: information update. Autism 1999; 3:299–307Google Scholar

34. Tsatsanis KD, Foley C, Donehower C: Contemporary outcome research and programming guidelines for Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Topics in Language Disorders 2004; 24:249–259Google Scholar

35. National Research Council: Educating Children With Autism. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001Google Scholar

36. Attwood T: Strategies for improving the social integration of children with Asperger syndrome. Autism 2000; 4:85–100Google Scholar

37. Fisher N, Happé F: A training study of theory of mind and executive function in children with autistic spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2005; 35:757–771Google Scholar

38. LaCava PG, Golan O, Baron-Cohen S, Myles BS: Using assistive technology to teach emotion recognition to students with Asperger syndrome: a pilot study. Remedial and Special Education 2007; 28:174–181Google Scholar

39. Turner-Brown LM, Perry TD, Dichter GS, Bodfish JW, Penn DL: Brief report: feasibility of social cognition and interaction training for adults with high functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord (Epub ahead of print, Feb 2, 2008)Google Scholar