Disruption of Existing Mental Health Treatments and Failure to Initiate New Treatment After Hurricane Katrina

Abstract

Objective: The authors examined the disruption of ongoing treatments among individuals with preexisting mental disorders and the failure to initiate treatment among individuals with new-onset mental disorders in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Methods: English-speaking adult Katrina survivors (N=1,043) responded to a telephone survey administered between January and March of 2006. The survey assessed posthurricane treatment of emotional problems and barriers to treatment among respondents with preexisting mental disorders as well as those with new-onset disorders posthurricane. Results: Among respondents with preexisting mental disorders who reported using mental health services in the year before the hurricane, 22.9% experienced reduction in or termination of treatment after Katrina. Among those respondents without preexisting mental disorders who developed new-onset disorders after the hurricane, 18.5% received some form of treatment for emotional problems. Reasons for failing to continue treatment among preexisting cases primarily involved structural barriers to treatment, while reasons for failing to seek treatment among new-onset cases primarily involved low perceived need for treatment. The majority (64.5%) of respondents receiving treatment post-Katrina were treated by general medical providers and received medication but no psychotherapy. Treatment of new-onset cases was positively related to age and income, while continued treatment of preexisting cases was positively related to race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic whites) and having health insurance. Conclusions: Many Hurricane Katrina survivors with mental disorders experienced unmet treatment needs, including frequent disruptions of existing care and widespread failure to initiate treatment for new-onset disorders. Future disaster management plans should anticipate both types of treatment needs.

Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in late August of 2005 and has since become the most costly natural disaster in U.S. history (1 , 2) . Levee breaches in New Orleans and hurricane aftermath in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi directly affected more than 1.5 million people, of whom over one-third were displaced. Relief efforts in disasters usually focus on immediate needs such as shelter, food, first aid, and treating acute medical conditions (3 , 4) , and the response to Katrina generally followed this approach (5) .

Accounts of the disaster and the affected populations suggest that the mentally ill might have been hit especially hard. Prior to the disaster, people residing in Katrina’s path were already among the sickest and poorest in the nation (6) . Widespread experience of trauma may have exacerbated preexisting mental disorders and produced new-onset disorders (7) . Delivery systems were decimated, creating financial and structural barriers to care that may have been especially difficult for the mentally ill to overcome (8) .

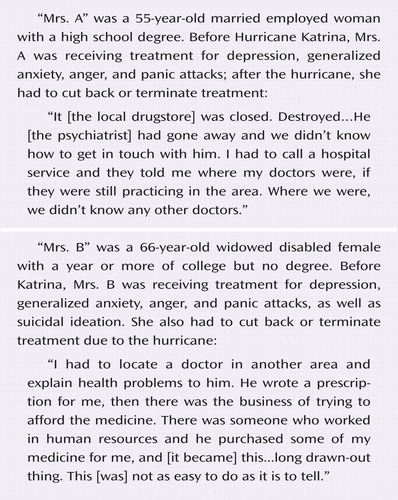

Under such circumstances, Katrina survivors with mental disorders may have experienced two types of unmet treatment needs. Those with preexisting mental disorders who had been receiving ongoing treatment before Katrina may have experienced disruptions in care because of new competing demands or the loss of providers, facilities, pharmacies, records, or means of payment (9) ; whether emergency services helped compensate for such disruptions (e.g., through rapid clinical assessment or maintenance of prehurricane treatments, including pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy) remains unclear. Unmet treatment needs may also have occurred among Katrina survivors without prior mental illness who experienced new disorders after the hurricane. In addition to facing the barriers already mentioned, those with new cases of mental illness may have failed to initiate treatment because of attitudinal factors such as low perception of need or stigma (10) .

The present study examined both the disruption of existing treatments and the failure to initiate treatment in a study cohort of Katrina survivors. We assessed self-reported barriers to obtaining care for individuals who experienced treatment disruption or failed to initiate treatment and identified the modes and sectors of treatment used by individuals receiving post-Katrina mental health services. Finally, we identified correlates of both disruption of existing treatment and failure to initiate new treatment as a means of informing the design and target of future interventions for disaster survivors with mental disorders.

Method

Respondents

Data for this study came from the Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group, a longitudinal study of prehurricane residents of the counties in Alabama and Mississippi and parishes in Louisiana directly affected by Katrina, as defined by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) (7) . From this target population of residents we recruited English-speaking adults (≥18 years of age) either by random-digit-dial telephone calls or from the American Red Cross’s database of families applying for assistance (roughly 1.4 million). Prehurricane residents of the New Orleans metropolitan area were oversampled. Potential participants were informed that joining the study required a commitment to participate in a number of follow-up surveys over several years and providing forwarding information if they moved. Respondents who gave verbal informed consent to participate (N=1,043) were administered the survey, the results of which are presented here. The Harvard Medical School Human Subjects Committee approved the consent procedures.

Respondents represented 41.9% of all individuals recruited for participation. Responses to a brief questionnaire administered to all potential participants were used to weight the participant study group to adjust for somewhat lower trauma exposure and prevalence of hurricane-related psychological distress than among nonparticipants. Other weights adjusted for probability of selection and residual discrepancies between the cohort and the 2000 Census population of the affected areas. The consolidated cohort sample weight was trimmed to increase design efficiency based on evidence that trimming did not significantly affect prevalence estimates of mental disorders. More details on the study cohort and sample weighting are reported elsewhere (www.hurricaneKatrina.med.harvard.edu).

Measures

Mental illness

The K-6 screening scale, a six-question short-form dimensional assessment of non-specific psychological distress (11) , was used to screen for probable posthurricane DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders within 30 days of the interview (12) . Because of the frequent comorbidity between anxiety and mood disorders and other mental disorders, many respondents with other mental disorders are also captured by assessments such as the K-6 scale. Based on previous K-6 scale validation studies (11) , scores in the range of 8 to 24 were classified as probable cases, while scores in the range of 0 to 7 were classified as probable noncases. A small clinical reappraisal study carried out in a stratified (by severity) subsample of 10 probable cases and five probable noncases using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (13) confirmed the K-6 classifications for all 15 respondents. No comparable screening information was obtained about prevalence of anxiety or mood disorders prior to the hurricane. However, at the time of interview respondents were asked to complete a chronic conditions checklist for the 12 months before the hurricane, including two items (“depression” or “any other mental health problem”) that asked superficially about mental disorders.

Treatment

All respondents who received professional counseling for emotional problems after the hurricane were asked about the number of sessions received, the duration of these sessions, and the types of professionals seen. Professionals were classified as psychiatrists; other mental health specialists (psychologist, psychotherapist, or any form of mental health counselor); general medical providers (primary care doctor, other general medical doctor or nurse, or any other health professional not previously mentioned); human services professionals (religious or spiritual advisor or social worker); or complementary/alternative medicine professionals (any other type of healer such as chiropractor, herbalist, or spiritualist). Respondents who received fewer than eight counseling sessions or sessions lasting an average of less than 30 minutes were classified as receiving “counseling,” while those who received eight or more sessions lasting an average of at least 30 minutes were classified as receiving “psychotherapy.” All respondents who received medication for emotional problems after the hurricane were asked the name of the medication and the length of time it was taken.

Respondents who did not report prehurricane mental illness but screened positive on the K-6 scale for psychological distress and did not receive any treatment (counseling or medication) were asked a series of questions about their reasons for failing to obtain treatment (14 – 16) , including perceived need (e.g., perceived presence or severity of mental illness), enabling factors (e.g., health insurance and other determinants of access to care), and predisposing factors (e.g., stigma or perceived effectiveness). Respondents with a prehurricane mental illness who reduced or stopped treatment because of the hurricane were asked a comparable series of questions about their reasons for reduction or termination of treatment.

Sociodemographic correlates

The sociodemographic variables assessed included age (18–39, 40–59, or 60+); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or other); family income (as measured by the ratio of pre-tax income to number of family members and compared to the population median; low=<50%, low to average=50%–100%, high to average=100%–300%, and high=>300%); years of education (0–11, 12 [high school graduate], 13–15, or 16+ [college graduate]); and number of residential moves since the hurricane (0, 1, or >1).

Data Analysis

Distributions of mental health service use in specific treatment sectors and for specific modes of treatment were estimated separately for respondents with preexisting mental disorders and for respondents with new-onset mental disorders after the hurricane. Frequency distributions of reasons for reducing or terminating treatment among respondents with prehurricane disorders and for respondents with new disorders not seeking treatment were examined. Sociodemographic correlates of mental health service use were examined with logistic regression analysis (17) ; to avoid multicollinearity, single variables were examined using bivariate models. All analyses were carried out using the Taylor series linearization method (18) . Significance was assessed using Wald chi-square statistics based on design-corrected coefficient variance-covariance matrices.

Results

Initiation and Continuity of Treatment

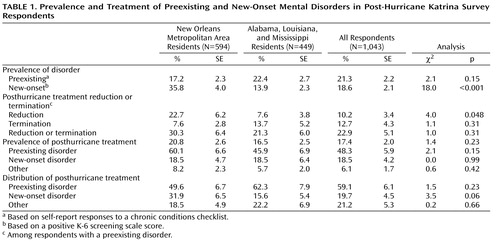

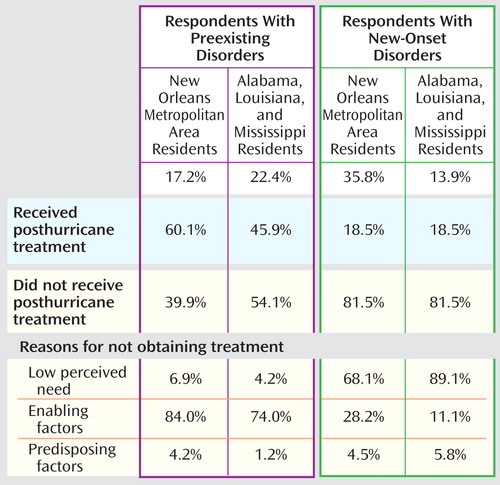

An estimated 21.3% of respondents reported having a mental disorder in the 12 months before the hurricane ( Table 1 ). More than one-fifth (22.9%) of those with a prehurricane mental disorder reported either reducing (10.2%) or terminating (12.7%) treatment because of the hurricane. Despite these reductions in treatment, close to half (48.3%) of the respondents with a prehurricane mental disorder received some type of treatment for emotional problems since the hurricane.

An estimated 18.6% of respondents without a prehurricane mental disorder met criteria for a DSM-IV mental disorder in the survey ( Table 1 ). This prevalence was significantly higher for respondents residing in the New Orleans metropolitan area than for others (35.8% versus 13.9%; χ 2 =18.0, p<0.001). Less than one-fifth (18.5%) of these new-onset cases received any treatment for emotional problems since the hurricane.

A small percentage (6.1%) of respondents received treatment for emotional problems subsequent to the hurricane despite not having an apparent mental disorder (preexisting or new-onset), although these respondents could have another disorder not captured by the screening measure. Because the majority of respondents in this study did not have an apparent mental disorder, they represent 21.2% of individuals receiving treatment for emotional problems after the hurricane. A much larger proportion of respondents receiving treatment (59.1%) had prehurricane mental disorders, while the remaining 19.7% had new-onset mental disorders.

Sector and Mode of Treatment for New and Continuing Patients

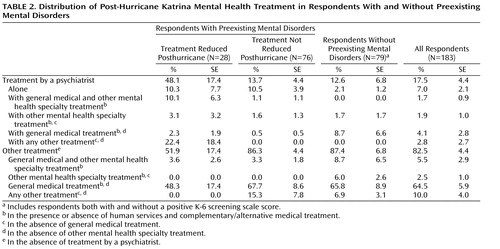

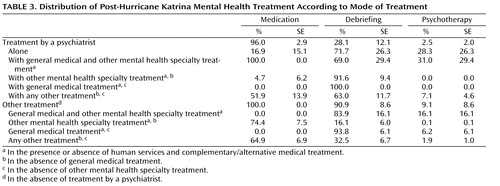

An estimated 17.5% of respondents seeking treatment for emotional problems subsequent to the hurricane were treated by a psychiatrist. This included 7% who were exclusively treated by a psychiatrist, 5.8% who also saw a general medical provider, and 3.6% who also saw another mental health specialist ( Table 2 ). By far the most common treatment provider was a general medical doctor in the absence of either a psychiatrist or any other mental health specialist (64.5%). Joint treatment by a general medical provider and a nonpsychiatrist mental health specialist was comparatively uncommon (5.5%). Psychiatrists were more involved in treating respondents with a prehurricane disorder who reduced treatment (48.1%) than either respondents with a prehurricane disorder who did not reduce treatment (13.7%) or other respondents (12.6%).

Respondents seen by a psychiatrist were no more likely to receive medication (51.9%) than respondents seen in other treatment sectors (64.9%), although the small proportion of respondents seen only by a psychiatrist almost invariably received medication (96%) ( Table 3 ). The same was true for respondents seen jointly either by a psychiatrist and other mental health specialist (100% received medication) or by a general medical provider and a nonpsychiatrist mental health specialist (100% received medication). Respondents seen by a psychiatrist were more likely to receive psychological counseling (63%) than those seeking treatment in other sectors (32.5%). Only a small proportion of respondents received psychotherapy, whether they were seen by a psychiatrist (7.1%) or in other treatment sectors (1.9%).

Reasons for Failing to Initiate or Continue Treatment

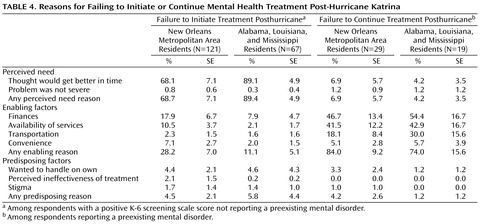

The most common reason respondents reporting new-onset mental disorders after the hurricane failed to initiate treatment was low perceived need, especially the belief that the symptoms would get better with time and on their own ( Table 4 ). It is noteworthy that this type of reason was reported significantly less by respondents residing in the New Orleans metropolitan area (68.7%) than by respondents residing elsewhere (89.4%; χ 2 =5.6, p=0.019). Barriers to treatment involving enabling factors (e.g., financial barriers or unavailability of services) were reported much less, although they were reported significantly more by residents of the New Orleans metropolitan area than by those residing elsewhere (28.2% versus 11.1%; χ 2 =3.8, p=0.051). Barriers to treatment involving predisposing factors (e.g., stigma or perceived ineffectiveness of treatment) were rare (4.5%–5.8%).

Reasons for reducing or terminating prehurricane treatment among respondents reporting a mental disorder prior to the hurricane were quite different from the reasons associated with failing to initiate treatment. Barriers to treatment involving enabling factors (largely financial barriers and availability of services for respondents residing in the New Orleans metropolitan area, plus transportation problems for the remainder of respondents) were by far the most commonly reported reasons for reducing or terminating prehurricane treatment, for respondents both in the New Orleans metropolitan area (84%) and elsewhere (74%) ( Figure 1 ). Barriers to treatment involving low perceived need for treatment (4.2%–6.9%) and predisposing factors (1.2%–4.2%) were much less common.

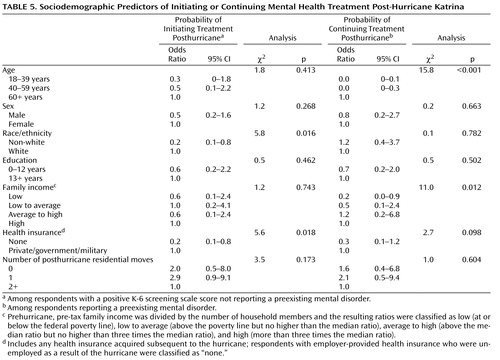

Sociodemographic Correlates of Treatment

The odds of receiving treatment among respondents reporting new-onset mental disorders after the hurricane were significantly lower for non-white respondents than for white respondents and for those without health insurance than for those with health insurance ( Table 5 ). Age, gender, education, family income before the hurricane, and number of moves after the hurricane were not significantly related to treatment.

The odds of continuing prehurricane treatment without reduction among respondents reporting a mental disorder prior to the hurricane were significantly lower for younger respondents than for older respondents and for those respondents with comparatively low prehurricane family income.

Discussion

These results should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, the study excluded people that could not be reached by telephone; as a result, the most disadvantaged and possibly most severely ill are underrepresented in the survey. Systematic nonresponse (i.e., higher survey refusal rates for individuals with mental disorders than for individuals without mental disorders) or systematic nonreporting (i.e., recall failure, conscious nonreporting, or error in diagnostic evaluation) are also possible. Prior studies suggest that nonresponse and nonreporting lead to underreporting of traumatic events as well as underreporting of mental disorders resulting from traumatic experiences, therefore resulting in an underestimation of unmet treatment needs (19) .

Second, psychopathology was not assessed using structured diagnostic instruments but by chronic condition checklists and a screening scale. For the K-6 screening scale, diagnostic concordance with clinical interviews has been consistently good, both in our small reappraisal of Katrina survivors and in earlier methodological studies (11 , 20) . However, individual-level imprecision regarding diagnoses may have increased because of the use of such measures.

Third, corroborating data on treatments were lacking, so it is possible that the self-reported information on mental health service use is somewhat biased. Some investigators have found that self-reports of treatments may overestimate mental health service use in administrative records, especially regarding the frequency of visits (21) . Finally, the study’s cross-sectional design prevents us from concluding that the observed correlates and reasons are causally related to mental health service use.

With these limitations in mind, the results of this study reveal that two forms of unmet treatment needs were common among Katrina survivors with mental disorders: disruption of existing treatments among individuals with prior needs and failure to initiate treatment among individuals with new needs. Over one-fifth (21.3%) of respondents reported having an active mental disorder in the 12 months before the hurricane, a somewhat higher estimate than previously reported in the two Census Divisions subsequently affected by Katrina (7 , 22) . Among respondents with preexisting disorders, over one-fifth experienced disruptions in care after the hurricane, including roughly equal proportions of respondents receiving fewer mental health services and respondents receiving no mental health services post-Katrina. Among respondents not reporting mental disorders in the year before the hurricane, 18.6% developed new-onset disorders; this percentage was significantly higher for respondents residing in metropolitan New Orleans than for those residing in other affected areas. Only one-fifth of respondents with new-onset disorders received any treatment during the posthurricane period. The limited data available on mental health service use after disasters corroborate our findings. Among evacuees living in Louisiana FEMA shelters, parents reported difficulties maintaining and initiating mental health treatments for both themselves and their children (23) . Even after disasters not marked by large-scale displacement or destruction, many with mental health needs experience difficulty accessing or continuing care (24 – 28) .

Our findings of frequent disruption in existing treatments and widespread failure to initiate new treatment may not be surprising, given the already high levels of undertreatment in the U.S. (29) and the fact that Katrina affected individuals (mostly racial or ethnic minorities) who were among the poorest in the nation before the hurricane. However, these results may not be unique to Katrina survivors and could possibly generalize to those populations that would be adversely impacted by future catastrophes. Unfortunately, both individuals with lesser financial means and racial and ethnic minorities have been shown to be at higher risk of psychological harm from disasters, even though they possess fewer resources and means of support to cope with the hardships resulting from such catastrophes (30 – 32) .

Furthermore, following Hurricane Katrina there was widespread loss of mental health care facilities, treatments, and personnel, as well as the loss of employment and the financial resources and insurance to pay for care (8 , 33 , 34) . These losses were greatest in New Orleans, which perhaps explains why reductions in existing treatment were more common here than in other affected areas. Such losses of infrastructure, personnel, and financial means to pay for treatment are reflected in our findings, as the vast majority of respondents with preexisting disorders indicated “lack of enabling factors” as the reason for disruption of treatment. Mental disorders are also often associated with low perceived need for treatment, high levels of stigma, and even avoidance for fear of reexperiencing painful memories (10 , 35) . These attitudinal barriers to treatment appear to explain why many respondents with new-onset disorders did not seek any treatment after Katrina.

The negative consequences of both forms of unmet treatment needs are uncertain. Katrina survivors with mental disorders could conceivably have had their symptoms quickly dissipate without treatment and without long-term consequences. However, earlier studies have shown that most cases of posttraumatic stress disorder have durations of more than 1 year (36) , with more than one-third failing to recover after many years. Furthermore, time to remission is nearly twice as long for untreated individuals than for those receiving treatment (19) . Dysfunction, development of comorbidity, and suicidality have been associated with even subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (19 , 37 , 38) .

The mental health services that Katrina survivors did receive are likely to reflect both what was available at the time and patients’ preferences. Most survivors used the general medical sector for mental health care, which emphasizes the importance of training and supporting primary care personnel in delivering quality mental health treatment in disaster settings. One means of doing so might be to increase the comanagement of cases by general medical and mental health specialty personnel, a practice that was exceedingly rare among Katrina survivors. While psychiatrists saw only a small proportion of cases overall, they had provided treatment to nearly half of those with preexisting cases experiencing posthurricane disruptions in care; such findings may indicate a particular role for the psychiatry sector in ensuring treatment continuity during disasters. Pharmacotherapy was the most commonly used mode of treatment for emotional problems, suggesting that current initiatives, most importantly the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Strategic National Stockpile of emergency medications, include frequently used psychotropic classes of medication (39) . Use of psychological counseling was much less common, despite prior research showing that this mode of treatment may be preferable to pharmacotherapy in largely underserved minority populations (40 , 41) . Psychiatrists were more likely to deliver some form of counseling, suggesting they might be useful in increasing use of psychotherapy in future disasters.

1. Rosenbaum S: US health policy in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. JAMA 2006; 295:437–440Google Scholar

2. Hurricane Katrina: What Government Is Doing. US Department of Homeland Security. http://www.dhs.gov/xprepresp/programs/gc_1157649340100.shtmGoogle Scholar

3. Ahern M, Kovats RS, Wilkinson P, Few R, Matthies F: Global health impacts of floods: epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiol Rev 2005; 27:36–46Google Scholar

4. Shultz JM, Russell J, Espinel Z: Epidemiology of tropical cyclones: the dynamics of disaster, disease, and development. Epidemiol Rev 2005; 27:21–35Google Scholar

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Public health response to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita—United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006; 55:229–231Google Scholar

6. Health: United States, 2004: DHHS Publication PHS 2004-1232. Hyattsville, Md. National Center for Health Statistics, 2005Google Scholar

7. Kessler RC, Galea S, Jones RT, Parker HA: Mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Bull World Health Organ 2006; 84:930–939Google Scholar

8. Berggren RE, Curiel TJ: After the storm–health care infrastructure in post-Katrina New Orleans. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1549–1552Google Scholar

9. Nutting PA, Rost K, Smith J, Werner JJ, Elliot C: Competing demands from physical problems: effect on initiating and completing depression care over 6 months. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9:1059–1064Google Scholar

10. Kaskutas LA, Weisner C, Caetano R: Predictors of help seeking among a longitudinal sample of the general population, 1984–1992. J Stud Alcohol 1997; 58:155–161Google Scholar

11. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand SL, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM: Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:184–189Google Scholar

12. Serious psychological distress, in Early Release of Selected Estimates Based on Data From the January–March 2004 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/earlyrelease200409.pdfGoogle Scholar

13. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 2002Google Scholar

14. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral health model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995; 36:1–10Google Scholar

15. Haas JS, Phillips KA, Sonneborn D, McCulloch CE, Baker LC, Kaplan CP, Perez-Stable EJ, Liang SY: Variation in access to health care for different racial/ethnic groups by the racial/ethnic composition of an individual’s county of residence. Med Care 2004; 42:707–714Google Scholar

16. Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, Aday LA: Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Serv Res 1998; 33:571–596Google Scholar

17. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed. New York, Wiley, 2000Google Scholar

18. Wolter KM: Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1985Google Scholar

19. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Google Scholar

20. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM: Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002; 32:959–976Google Scholar

21. Rhodes AE, Fung K: Self-reported use of mental health services versus administrative records: care to recall? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004; 13:165–175Google Scholar

22. Kessler RC, Merikangas KR: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004; 13:60–68Google Scholar

23. Responding to an Emerging Humanitarian Crisis in Louisiana and Mississippi: Urgent Need for a Health Care “Marshall Plan.” New York, Children’s Health Fund, April 2006. http://www.childrenshealthfund.org/whatwedo/operation-assist/pdfs/On%20the%20Edge_Final.pdfGoogle Scholar

24. Boscarino JA, Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Vlahov D: Utilization of mental health services following the September 11th terrorist attacks in Manhattan, New York City. Int J Emerg Ment Health 2002; 4:143–155Google Scholar

25. Boscarino JA, Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Vlahov D: Psychiatric medication use among Manhattan residents following the World Trade Center disaster. J Trauma Stress 2003; 16:301–306Google Scholar

26. DeLisi LE, Maurizio A, Yost M, Papparozzi CF, Fulchino C, Katz CL, Altesman J, Biel M, Lee J, Stevens P: A survey of New Yorkers after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:780–783Google Scholar

27. Lindy JD, Grace MC, Green BL: Survivors: outreach to a reluctant population. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1981; 51:468–478Google Scholar

28. Stuber J, Galea S, Boscarino JA, Schlesinger M: Was there unmet mental health need after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006; 41:230–240Google Scholar

29. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:629–640Google Scholar

30. Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Gold J, Bucuvalas M, Kilpatrick D, Stuber J, Vlahov D: Posttraumatic stress disorder in Manhattan, New York City, after the September 11th terrorist attacks. J Urban Health 2002; 79:340–353Google Scholar

31. Galea S, Vlahov D, Tracy M, Hoover DR, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D: Hispanic ethnicity and post-traumatic stress disorder after a disaster: evidence from a general population survey after September 11, 2001. Ann Epidemiol 2004; 14:520–531Google Scholar

32. Norris FH: Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:409–418Google Scholar

33. Dewan S, Connelly M, Lehren A: Evacuees’ lives still upended seven months after hurricane. New York Times, March 22, 2006, p A1Google Scholar

34. Zwillich T: Health care remains basic in New Orleans. Lancet 2006; 367:637–638Google Scholar

35. Schwarz ED, Kowalski JM: Malignant memories: reluctance to utilize mental health services after a disaster. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:767–772Google Scholar

36. Breslau N, Davis GC: Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: risk factors for chronicity. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:671–675Google Scholar

37. Marshall RD, Olfson M, Hellman F, Blanco C, Guardino M, Struening EL: Comorbidity, impairment, and suicidality in subthreshold PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1467–1473Google Scholar

38. Stein MB, Walker JR, Hazen AL, Forde DR: Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1114–1119Google Scholar

39. Emergency Preparedness and Response: Strategic National Stockpile. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.bt.cdc.gov/stockpile/index.aspGoogle Scholar

40. Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB: Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2000; 15:527–534Google Scholar

41. Dwight-Johnson M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Tang L, Wells KB: Can quality improvement programs for depression in primary care address patient preferences for treatment? Med Care 2001; 39:934–944Google Scholar