Efficacy and Safety of Extended-Release Venlafaxine in the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Children and Adolescents: Two Placebo-Controlled Trials

Abstract

Objective: The authors evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of extended-release venlafaxine in the treatment of pediatric generalized anxiety disorder. Method: Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials were conducted at 59 sites in 2000 and 2001. Participants 6 to 17 years of age who met DSM-IV criteria for generalized anxiety disorder received a flexible dosage of extended-release venlafaxine (N=157) or placebo (N=163) for 8 weeks. The primary outcome measure was the composite score for nine delineated items from the generalized anxiety disorder section of a modified version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, and the primary efficacy variable was the baseline-to-endpoint change in this composite score. Secondary outcome measures were overall score on the nine delineated items, Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders, and the severity of illness and improvement scores from the Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI). Results: The extended-release venlafaxine group showed statistically significant improvements in the primary and secondary outcome measures in study 1 and significant improvements in some secondary outcome measures but not the primary outcome measure in study 2. In a pooled analysis, the extended-release venlafaxine group showed a significantly greater mean decrease in the primary outcome measure compared with the placebo group (–17.4 versus –12.7). The response rate as indicated by a CGI improvement score <3 was significantly greater with extended-release venlafaxine than placebo (69% versus 48%). Common adverse events were asthenia, anorexia, pain, and somnolence. Statistically significant changes in height, weight, blood pressure, pulse, and cholesterol levels were observed in the extended-release venlafaxine group. Conclusions: Extended-release venlafaxine may be an effective, well-tolerated short-term treatment for pediatric generalized anxiety disorder.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric illnesses in children and adolescents (1 – 3) , and the prevalence rates of generalized anxiety disorder or overanxious disorder have been estimated to be as high as 15% (4) . However, most children with anxiety disorders do not receive treatment (5) or are misdiagnosed, treated incorrectly, or poorly monitored (6 , 7) . Data on the pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders in pediatric patients are limited, although the use of psychotropic medications has increased dramatically (8) .

In adults with generalized anxiety disorder, favorable responses have been obtained with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (9 – 11) , and these agents are considered the first choice of pharmacological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children and adolescents (12) . Open-label (13 , 14) and controlled studies (15 – 17) demonstrate the short-term efficacy and safety of several SSRIs, including fluoxetine (13 , 14 , 17) , fluvoxamine (15) , and sertraline (16) , in treating pediatric anxiety disorders. Only one relatively small (N=22) study of sertraline (16) has evaluated treatment in children with a specific diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder. Extended-release venlafaxine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is an effective treatment for generalized anxiety disorder in adults (18 , 19) . However, no data from randomized controlled trials of extended-release venlafaxine in pediatric generalized anxiety disorder have been published.

We report the results of two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, flexible-dose trials comparing the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of extended-release venlafaxine and placebo in the treatment of children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder.

Method

Study Participants

Diagnosis and Inclusion Criteria

Participants were outpatient children (age 6 to 11 years) or adolescents (age 12 to 17 years) who met DSM-IV criteria for generalized anxiety disorder according to the generalized anxiety disorder section of the Columbia Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (Columbia K-SADS; 20). In the Columbia K-SADS, the original K-SADS (21) is modified such that each component of the DSM-IV criteria for a disorder (in this case generalized anxiety disorder) is specifically inquired about and rated. All participants had a total score ≥20 on the severity component of the generalized anxiety disorder section (five items), with all severity item scores ≥4 (moderate); a total score ≥7 on the impairment component (four items), with a score ≥4 on the clinical global impairment in functioning item; a score <45 on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised (22) ; a score ≥4 on the severity of illness item of the Clinical Global Impression scale ( 23 ; CGI) at prestudy screen and baseline; and anxiety symptoms for at least 6 months before enrollment in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Minimum body weight was 25 kg, and participants had to be able to swallow capsules. Participants were excluded if they had concurrent major depressive disorder, acute suicidality, social anxiety or separation anxiety disorder, or a concurrent psychiatric disorder as confirmed by the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version (24) ; a concurrent mental disorder due to a general medical condition; a recent history of drug or alcohol dependence or abuse; a history of a seizure disorder, a psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, anorexia, or bulimia; a first-degree relative with bipolar disorder; use of venlafaxine in the past 6 months, fluoxetine within 35 days, investigational drugs, antipsychotics, or ECT within the past 30 days, or monoamine oxidase inhibitors, triptans, or herbal products within the past 14 days; or use of any other antidepressants, anxiolytics, sedative-hypnotics, stimulants, other psychotropic drugs (e.g., psychostimulants, buspirone, and lithium), or substances or nonpsychopharmacological drugs with psychotropic effects (e.g., antihistamines and anticonvulsants) (except if on a stable dose for >1 month) within 7 days of the start of double-blind treatment. Concurrent psychotherapy was permitted only if it had been well established before the study began.

Study Design

Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, flexible-dose trials of an identical design, developed in response to a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) request, were conducted at a total of 59 clinical sites in the United States. Study 1 was conducted at 29 sites from April 2000 to August 2001; study 2 was conducted at 37 sites from August 2000 to September 2001. Seven sites that had completed enrollment for study 1 were allowed to enroll patients for study 2 and participated in both trials. The institutional review boards of all study centers approved the trials. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of participants before enrollment, and participants provided signed and witnessed assent.

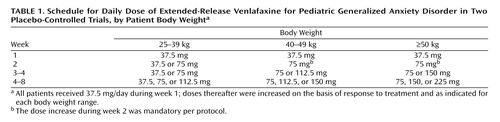

After a 4- to 10-day single-blind placebo lead-in period, eligible participants were stratified by age into two groups—children (6–11 years) and adolescents (12–17 years)—then randomly assigned to receive extended-release venlafaxine or placebo for 8 weeks, followed by a taper period of up to 14 days. Participants had weekly appointments for evaluations, except at week 5, when no visit was scheduled. Treatment with extended-release venlafaxine was started at 37.5 mg/day and titrated upward according to body weight ( Table 1 ). The maximum dose was 225 mg/day for participants weighing ≥50 kg.

Outcome Measures and Schedule of Assessments

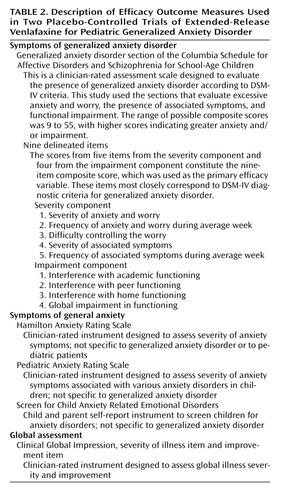

Efficacy was evaluated with outcome measures that assess specific symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, general anxiety, and global well-being ( Table 2 ). The primary outcome measure was the composite score of nine delineated items from the Columbia K-SADS generalized anxiety disorder section, which was administered at each visit. The primary efficacy variable was the baseline-to-endpoint change in nine-item composite score. Secondary efficacy assessments were administered as follows: the complete generalized anxiety disorder section at screening, baseline, and weeks 4 and 8; the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (25) at baseline and all weekly visits; the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (26) and the parent and child forms of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (27 , 28) at baseline and weeks 4 and 8; the CGI global improvement item at all weekly visits; and the CGI severity of illness item at screening and all weekly visits.

Safety Assessments and Schedule

A physical examination (including height), laboratory tests, and ECG were performed at screening and at week 8. Adverse events, vital signs, and body weight were recorded at all visits. Serious adverse events were reported to the sponsor for submission to the FDA through the Adverse Event Reporting System. If a participant left the study before the final visit, safety evaluations were conducted on the last day on which the participant took a full dose of study medication (i.e., before drug taper) or as soon as possible thereafter.

Statistical Analyses

The data from both studies were analyzed separately and then pooled in a prospectively defined combined analysis. Efficacy analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat population, which included all participants who entered the double-blind period, took at least one dose of assigned medication, and, for the primary outcome measure, had a baseline evaluation and at least one on-therapy evaluation (i.e., an observation that occurred within 3 days of the last full dose). The primary efficacy time point was at week 8, using the last-observation-carried-forward method to account for missing data.

Changes from baseline for the primary and secondary outcome measures (except the CGI improvement score) were analyzed at each assessment point using repeated-measures analysis of covariance with treatment and investigator as factors and baseline as covariate. The same model was used to analyze the CGI improvement score, except that there was no baseline score to enter into the model.

Analysis of Response

Response was defined as a decrease of ≥50% from baseline in composite score on the nine delineated items of the Columbia K-SADS or in the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale score, or a CGI improvement score <3 (that is, 1 [“very much improved”] or 2 [“much improved”]).

Pooled Analysis

For the pooled analysis, the primary efficacy time point was the final on-therapy observation. All pooled analyses were performed on the primary efficacy variable (with the last observation carried forward) sequentially. Treatment-by-subgroup interactions were tested, and only significant terms for those interactions were included in the model used for analyzing the data presented in this report. Observed-cases data were also analyzed.

Subgroup Analyses

Subgroup analyses were performed on the pooled data for age group (6–11 years and 12–17 years), gender, and baseline illness severity.

Confirmatory Analyses

The statistical analyses described above were specified by the protocol and required by the FDA. The primary outcome measure (composite score on the nine items from the Columbia K-SADS generalized anxiety disorder section) was also analyzed using a mixed-effects likelihood-based repeated-measures random regression analysis (29 , 30) , with change from baseline to each visit as the dependent variable. The model included the fixed categorical effects of treatment, investigator, visit, and treatment-by-week interaction as well as the continuous fixed covariates of baseline score and baseline-by-week interaction. An unstructured (co)variance matrix was used to model the within-patient errors. The primary comparison was between the extended-release venlafaxine and placebo treatment groups at week 8 or the last visit at which participants received active study drug. Standard effect sizes were also calculated.

Sample Size and Power Calculations

Based on the expectation of response rates on the primary outcome measure of 60% and 30%, respectively, for the extended-release venlafaxine and placebo groups, a sample size of 63 participants per group in each study would have a 90% power to detect a significant difference between the treatment groups at the 5% level. To compensate for an estimated 5% of participants who might fail to qualify for inclusion in the intent-to-treat population, the statistical plan called for random assignment of 70 participants to each group.

Results

Participant Disposition

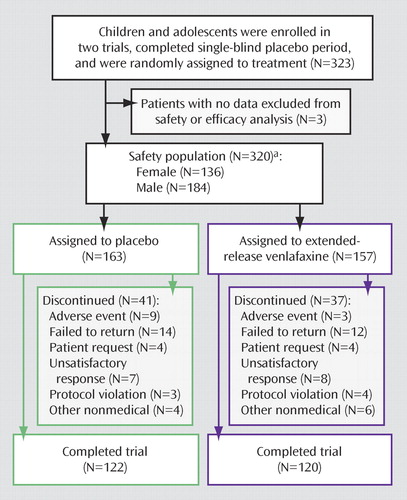

As shown in Figure 1 , a total of 323 children and adolescents entered the two trials; 320 of them were included in the safety analysis and 313 in the efficacy analysis. A total of 41 patients in the placebo group (25%) and 37 in the extended-release venlafaxine group (24%) left the study prematurely. During the double-blind period, nine participants from the placebo group (6%) and five from the extended-release venlafaxine group (3%) had at least one adverse event that was cited as a primary or secondary reason for discontinuation.

a Because seven patients from the safety population did not meet intent-to-treat criteria, only 313 patients were included in the efficacy analyses.

Baseline Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

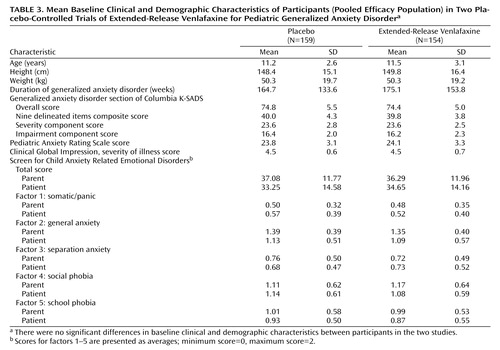

Since no statistically significant differences were found between the two studies, the baseline clinical and demographic characteristics are presented for the pooled efficacy population ( Table 3 ). The treatment groups were balanced with respect to age, gender, height, weight, duration of generalized anxiety disorder, and baseline scores on efficacy variables. In the pooled efficacy population, 133 patients were girls (56 in the extended-release venlafaxine group) and 180 were boys (98 in the extended-release venlafaxine group). A total of 237 patients were white (115 in the extended-release venlafaxine group), and 76 were of other ethnic origins (37 in the extended-release venlafaxine group). The majority of participants had long-standing generalized anxiety disorder (average duration, 170 weeks [SD=143.7]). Two patients in the extended-release venlafaxine group and three in the placebo group received concurrent psychotherapy. Baseline mean values on the individual factors of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders showed that anxiety symptoms were primarily related to generalized anxiety disorder, followed by social phobia and school phobia.

Efficacy Analysis

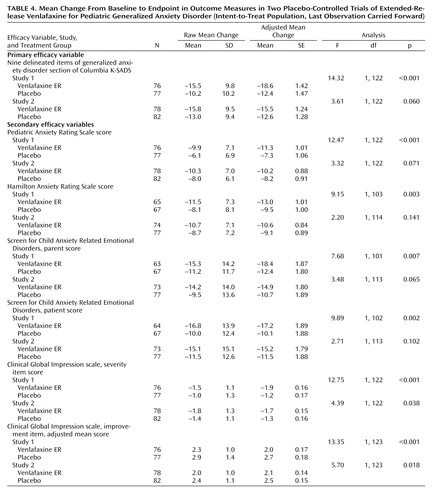

Mean baseline-to-endpoint changes for the primary and secondary outcome measures are listed in Table 4 . In study 1, the adjusted mean baseline-to-endpoint change in the primary outcome measure was significantly greater for participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group compared with those in the placebo group (F=14.32; df=1, 122, p≤0.001); in study 2, the between-group difference fell just short of statistical significance (F=3.61; df=1, 122, p=0.060).

On the severity component of the generalized anxiety disorder section of the Columbia K-SADS, improvement with extended-release venlafaxine was significantly greater than with placebo in both studies (study 1: F=16.17; df=1, 122, p<0.001; study 2: F=5.89; df=1, 122, p<0.05); improvement on the impairment component and on the overall generalized anxiety disorder section was significantly greater with extended-release venlafaxine in study 1 only (impairment: F=9.57; df=1, 122, p=0.002; complete section: F=11.27; df=1, 103, p=0.001). Participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group showed significantly greater improvement at endpoint compared with those in the placebo group on the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders, CGI improvement score, and CGI severity of illness score in study 1. Between-group differences in study 2 were statistically significant only for the CGI severity of illness and improvement scores.

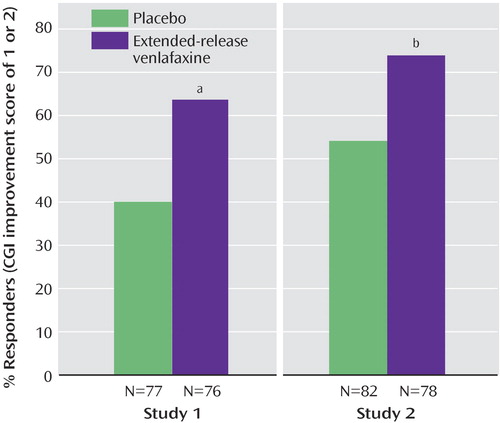

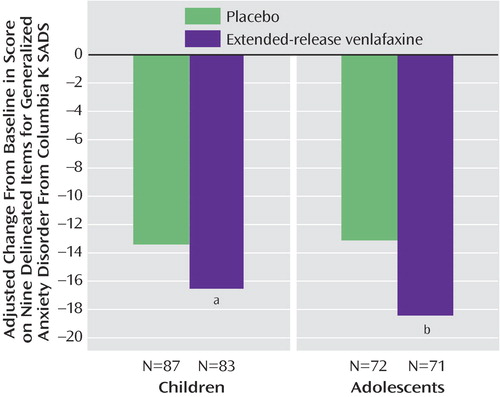

A significantly higher percentage of participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group than in the placebo group responded to treatment according to the primary outcome measure criterion in study 1 (38% versus 17%) but not in study 2. The percentage of participants who responded according to the criterion for Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale did not differ significantly between groups in study 1 or study 2. In both studies, a significant between-group difference was observed in the percentage of participants who met the response criterion for the CGI improvement score ( Figure 2 ).

a p=0.004.

b p=0.008.

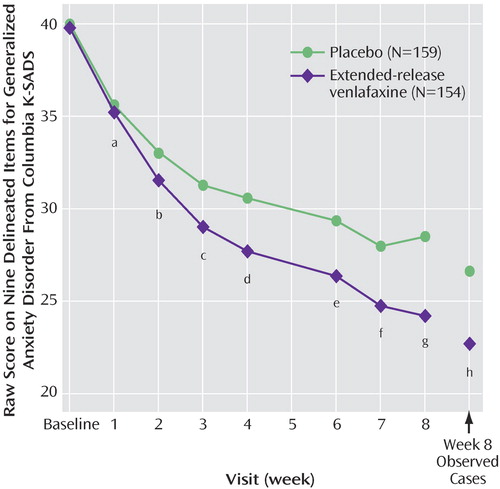

Pooled Analysis

Figure 3 summarizes the pooled data for the primary outcome measure over time. Participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group had an adjusted mean decrease of 17.4 points on their score on the nine delineated items of the Columbia K-SADS, compared with 12.7 points for the placebo group (F=17.74; df=1, 252, p<0.001).

a F=0.95, df=1, 244, p=0.331.

b F=4.72, df=1, 251, p=0.031.

c F=8.57, df=1, 252, p=0.004.

d F=10.89, df=1, 252, p=0.001.

e F=9.64, df=1, 252, p=0.002.

f F=9.72, df=1, 252, p=0.002.

g F=18.17, df=1, 252, p<0.001.

h Observed cases: N=116 for extended-release venlafaxine, N=116 for placebo; F=9.56; df=1, 163, p=0.002.

Response rates according to CGI improvement score criteria were 69% and 48% for the extended-release venlafaxine and placebo groups, respectively (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.004). The extended-release venlafaxine group also had a significantly greater decrease in impairment component scores than the placebo group from week 2 (F=6.55; df=1, 251, p=0.011) to endpoint (F=11.04; df=1, 252, p=0.001) and a significantly greater decrease in severity component scores from week 3 (F=8.38; df=1, 252, p=0.004) to endpoint (F=21.27; df=1, 252, p<0.001). Decreases in CGI severity of illness score were significantly greater in the extended-release venlafaxine group than in the placebo group from week 2 (F=10.35; df=1, 251, p=0.001) to endpoint (F=15.41; df=1, 252, p<0.001).

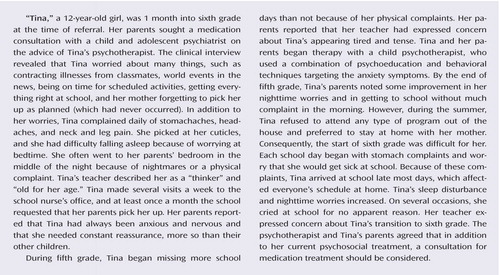

Subgroup Analysis

The adjusted mean decrease from baseline in the primary outcome measure was significantly greater for participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group than for those in the placebo group among both children (F=4.11; df=1, 120, p=0.045) and adolescents (F=8.85; df=1, 97, p=0.004) ( Figure 4 ). No differences were observed for gender and baseline illness severity.

a F=4.11, df=1, 120, p=0.045.

b F=8.85, df=1, 97, p=0.004.

Confirmatory Analyses

The results of the residual (restricted) maximum-likelihood-based mixed-effects repeated-measures random regression analysis show a statistically significant difference between treatment groups (F=11.58; df=1, 122, p=0.0009) in study 1 but not study 2. For the pooled data, the difference between treatment groups was statistically significant (F=12.13, df=1, 252, p=0.0006). Similar results were observed for the treatment-by-week interaction: significant differences were observed in slopes (F=2.5; df=5, 122, p=0.0339) and combined data (F=2.53; df=5, 252, p=0.0294) in study 1 but not study 2. Standard effect sizes were 0.53 for study 1, 0.31 for study 2, and 0.42 for the pooled data set.

Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events

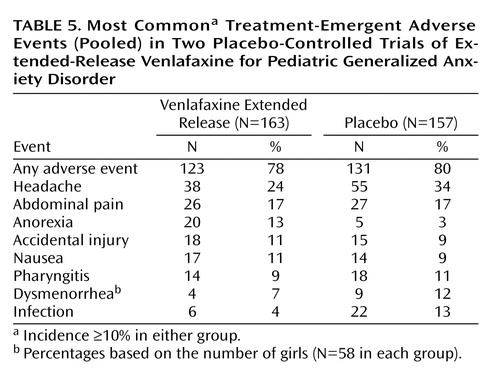

Treatment-emergent adverse events were generally mild to moderate in severity, and most tended to resolve with continued treatment. Table 5 lists the events that had an incidence ≥10% in either pooled treatment group. Treatment-emergent adverse events with an incidence ≥5% in the extended-release venlafaxine group and at least twice that of the placebo group were asthenia, pain, anorexia, and somnolence. Anorexia was the only event with an incidence that was ≥10% in the extended-release venlafaxine group and was at least twice that of the placebo group (13% versus 3%). Somnolence was the only event for which the incidence differed between children and adolescents, with a significantly higher incidence among adolescents in the extended-release venlafaxine group than those in the placebo group (11% versus 0%); among children, the incidence of somnolence was 4% for both treatment groups.

Treatment-emergent adverse events that were cited as a primary or secondary reason for discontinuation for ≥1% of participants during the on-therapy period were abnormal/changed behavior for two participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group (1%) (one with oppositional defiant behavior and one with acting out) and abdominal pain and nervousness, each of which were reported by two participants in the placebo group (1%).

Taper/poststudy-emergent adverse events—those that did not present during the last week of full dose of medication or that became more severe after the last week of full-dose medication—were reported by 32% of participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group and 16.5% of those in the placebo group (χ 2 =10.22, p=0.0014). Dizziness was the only such event with an incidence that was ≥5% in the extended-release venlafaxine group (N=8; 5%) and was at least twice that of the placebo group (N=2; 1%).

Serious Adverse Events

None of the participants experienced serious adverse events during the prestudy placebo lead-in period. Two participants in each treatment group (1%) had serious adverse events. Two participants, both from study 1, had suicidal ideation or made a suicide attempt, in both cases resulting in withdrawal from the study: a 10-year-old boy in the extended-release venlafaxine group withdrew on day 19 because of suicidal ideation, which occurred 2 days after the last full dose of extended-release venlafaxine, and a 17-year-old girl in the placebo group withdrew because of a suicide attempt (ingestion of 18 tablets of Excedrin PM, which contains acetaminophen and diphenhydramine) on day 15. In study 2, a withdrawal syndrome with agitation and confusion beginning approximately 24 hours after the last taper dose was reported for a 10-year-old girl in the extended-release venlafaxine group, and an 11-year-old boy in the placebo group was hospitalized with mononucleosis on day 3.

Medical Assessments

Laboratory Tests

None of the participants discontinued treatment because of abnormalities in laboratory test results, vital signs, weight, or ECG (discontinuation was at the investigator’s discretion; there were no a priori withdrawal criteria). Assessment of laboratory test results indicated only one clinically important difference between the treatment groups. Small but statistically significant mean increases from baseline in total serum cholesterol were observed for participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group (0.19 to 0.20 mmol/liter), which were significantly different from the decreases observed with placebo (0.04 to 0.05 mmol/liter). Final on-therapy mean increases from baseline for total serum cholesterol with extended-release venlafaxine observed in these studies were larger than those that have been observed in adult studies (0.026 mmol/liter; Effexor XR package insert, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Collegeville, Penn., 2004). One participant in the extended-release venlafaxine group had a clinically important increase in total cholesterol (defined as an increase of ≥1.29 mmol/liter and a value ≥6.72 mmol/liter). Three participants in the placebo group had clinically important increases in aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase concentrations (defined as ≥3 times the upper limit of normal).

ECG Results

An ECG-measured significant mean increase in heart rate of roughly 4 bpm from baseline was observed with extended-release venlafaxine as compared with a small but significant decrease (approximately 2 bpm) with placebo. There were no significant changes from baseline or between-group differences in QTc intervals. Clinically important ECG findings were observed in four participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group (abnormal right atrial rhythm; sinus rhythm with sinus tachycardia; normal sinus rhythm with short PR interval; and left atrial rhythm, rightward axis, and nonspecific ST abnormality) and one participant in the placebo group (first-degree atrioventricular block). None of these ECG changes were associated with adverse events, and all five participants completed the study.

Blood Pressure and Heart Rate

Four participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group and two in the placebo group had clinically important increases in blood pressure (i.e., values outside age-, sex-, and height-specific normal range). One participant in the extended-release venlafaxine group had a sustained increase in supine diastolic blood pressure (defined as an increase ≥10 mm Hg and outside age-, sex-, and height-specific normal range for three consecutive visits at least 7 days apart), but no participant discontinued treatment because of elevated blood pressure. At the final on-therapy evaluation, mean changes from baseline in supine pulse rate (extended-release venlafaxine: 4.42 bpm [p<0.001]; placebo: 1.26 bpm [n.s.]), supine diastolic blood pressure (extended-release venlafaxine: 2.15 mm Hg [p<0.01]; placebo: –0.53 mm Hg [n.s.]), and supine systolic blood pressure (extended-release venlafaxine: 2.50 mm Hg [p<0.001]; placebo: –1.17 mm Hg [n.s.]) were significantly different between groups (p=0.040, p=0.004, and p<0.001, respectively).

Weight

The mean change from baseline in body weight (extended-release venlafaxine, –0.43 kg [p<0.01]; placebo, 0.67 kg [p<0.001]) was statistically significant between groups (p<0.001). Weight loss of 7% or more occurred in 5% of participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group and 1% of those in the placebo group. Clinically important (determined by medical monitor) weight loss was observed in one participant in the extended-release venlafaxine group, and clinically important weight gain was observed in two participants in the placebo group.

Height

Mean height increased from baseline by 0.3 cm (p<0.05) among participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group and by 1.0 cm (p<0.001) among those in the placebo group, a clinically meaningful and statistically significant (p=0.041) difference between groups.

Discussion

In study 1, the extended-release venlafaxine group showed significantly greater improvement than the placebo group on all the outcome measures. In study 2, the extended-release venlafaxine group showed significantly greater improvement than the placebo group on some secondary outcome measures; the difference on the primary efficacy variable fell just short of significance. A substantial placebo response, similar to that reported in studies of adults with generalized anxiety disorder (18 , 19) , was observed in both studies. The placebo response was particularly evident in study 2, which may have contributed to its failure to show a statistical separation between extended-release venlafaxine and placebo. When data from the two studies were pooled, participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group showed statistically significant improvements compared with participants in the placebo group in the primary and all secondary outcome measures. On the nine delineated items of the Columbia K-SADS, the mean adjusted decrease in score was 17.4 for participants in the extended-release venlafaxine group, compared with 12.7 points for the placebo group. CGI improvement score response rates for the extended-release venlafaxine and placebo groups were 69% and 48%, respectively. The findings of the individual trials are not sufficient to establish the efficacy of extended-release venlafaxine in treating generalized anxiety disorder in pediatric patients according to FDA requirements, namely, two trials with statistically significant positive results on the primary outcome measure. Nonetheless, the pattern of improvement demonstrated in study 1, in the pooled analysis, and, to a lesser extent, in study 2, is clinically meaningful and similar to that observed in adult populations (18 , 19 , 31) .

Treatment with extended-release venlafaxine was generally well tolerated and was associated with few serious adverse events or clinically significant changes in safety assessment measures. However, the observation of statistically significant changes in total cholesterol, blood pressure, heart rate, weight, and height during short-term treatment suggests that there could be clinically meaningful changes associated with long-term treatment. Additional studies are needed to determine appropriate safety monitoring for pediatric patients during long-term treatment. Clinicians should consider monitoring basic growth, vital sign indices, and laboratory assessments (particularly cholesterol) with acute treatment, along with periodic ECG assessments during long-term treatment.

Pooling data from two identically designed studies allowed the identification of possible differential responses to extended-release venlafaxine in population subgroups that would not have been possible with a smaller sample. The results of the subgroup analyses of the pooled data showed that, based on the primary efficacy measure at the final on-therapy visit, extended-release venlafaxine appears to be an effective treatment for pediatric patients with generalized anxiety disorder, independent of age, gender, or baseline severity of illness.

Our study had several limitations. First, the trials were only 8 weeks long. Generalized anxiety disorder can have a chronic course, and, untreated, it can cause significant distress and functional impairment (2 , 32) . Many adult patients with generalized anxiety disorder require treatment beyond 6 months to prevent relapse (33) . The long-term efficacy of extended-release venlafaxine in adult populations with generalized anxiety disorder has been demonstrated (19 , 31) . Additional studies are needed to evaluate its long-term efficacy in pediatric populations.

Second, because of the extensive exclusion criteria, the population studied in these two trials is not representative of typical patients referred to child and adolescent psychiatrists; it may be more representative of untreated children and adolescents in the general community. The Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group, which studied patients who may be more representative of treatment populations, included three pediatric anxiety disorders—generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and social anxiety—and found these disorders to be highly comorbid (15) . Pediatric patients with generalized anxiety disorder presenting to their family physician frequently have concurrent mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders or take other psychoactive medications, all of which were exclusion criteria for the studies we report here. Given that many pediatric patients with generalized anxiety disorder have comorbid anxiety disorders (34) , patients who had symptoms of other anxiety disorders but did not meet full diagnostic criteria were allowed to participate. As in previous work on pediatric generalized anxiety disorder (15) , patients in our samples had symptoms of other anxiety disorders, particularly social anxiety.

Finally, the participating investigative sites were required to have a child and adolescent psychiatrist or a child psychologist who received reliability training during the study initiation meeting, but not during the study, which may have led to rater drift, particularly in terms of defining threshold and subthreshold diagnoses.

The 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (35) found annual incidences of 16.9% for suicidal ideation, 8.5% for suicide attempts, and 2.9% for suicide attempts requiring medical attention. Although this is a remarkable contrast to the low incidence of suicidal ideation in our sample, a recent history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempt was an exclusion criterion for the study. The low incidence of suicide-related adverse events in this study also may appear to contradict earlier guidance (36) cautioning prescribers that an increased incidence of hostility and suicide-related adverse events was observed in studies of pediatric patients with major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder treated with extended-release venlafaxine. However, that finding was based on data from the combined populations of studies of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Similarly, an FDA analysis (37) using pooled data from studies of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder found a relative risk of 4.97 (95% CI=1.09–22.72) for these events among patients treated with venlafaxine. Notably, although the FDA review used different, and perhaps more stringent, criteria to identify these events, only two events were reported in the generalized anxiety disorder studies (one in the venlafaxine group and one in the placebo group). The FDA report also commented that the signal (that is, the effect of exposure to extended-release venlafaxine as compared with placebo on the risk of these events) associated with extended-release venlafaxine was observed only in the major depressive disorder studies. It should be noted that the black box warning applies to all antidepressants and diagnoses. At this time, there are insufficient data to determine whether the risk of suicidality is higher or lower in patients with generalized anxiety disorder (37) .

Pediatric patients with depression seem to be at greater risk of suicidal ideation compared with pediatric patients with anxiety disorders. Nevertheless, clinicians must be cautious when making a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder and considering pharmacotherapy, since there may be comorbid symptoms or diagnoses that are associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation. Moreover, clinicians should always be alert to signs of suicidal ideation in pediatric patients when extended-release venlafaxine is prescribed.

In summary, this is the first report of results from randomized controlled clinical trials of extended-release venlafaxine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. The results of these two trials, with the data analyzed separately and pooled, suggest that extended-release venlafaxine may be effective and well tolerated in the short-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children and adolescents.

1. Labellarte MJ, Ginsburg GS, Walkup JT, Riddle MA: The treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:1567–1578Google Scholar

2. Pine DS: Childhood anxiety disorders. Curr Opin Pediatr 1997; 9:329–338Google Scholar

3. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME: NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:28–38Google Scholar

4. Costello EJ, Angold A: Epidemiology, in Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Edited by March JS. New York, Guilford, 1995, pp 109–115Google Scholar

5. Costello EJ, Janiszewski S: Who gets treated? factors associated with referral in children with psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990; 81:523–529Google Scholar

6. Jensen PS, Bhatara VS, Vitiello B, Hoagwood K, Feil M, Burke LB: Psychoactive medication prescribing practices for US children: gaps between research and clinical practice. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:557–565Google Scholar

7. Jensen PS, Kettle L, Roper MT, Sloan MT, Dulcan MK, Hoven C, Bird HR, Bauermeister JJ, Payne JD: Are stimulants overprescribed? treatment of ADHD in four US communities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:797–804Google Scholar

8. Zito JM, Safer DJ, DosReis S, Gardner JF, Magder L, Soeken K, Boles M, Lynch F, Riddle MA: Psychotropic practice patterns for youth: a 10-year perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003; 157:17–25Google Scholar

9. Rickels K, Zaninelli R, McCafferty J, Bellew K, Iyengar M, Sheehan D: Paroxetine treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:749–756Google Scholar

10. Allgulander C, Dahl AA, Austin C, Morris PLP, Sogaard JA, Fayyad R, Kutcher SP, Clary CM: Efficacy of sertraline in a 12-week trial for generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1642–1649Google Scholar

11. Davidson JR, Bose A, Korotzer A, Zheng H: Escitalopram in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: double-blind, placebo controlled, flexible-dose study. Depress Anxiety 2004; 19:234–240Google Scholar

12. Bernstein GA, Layne AE: Separation anxiety disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, in Child and Adolescent. Edited by Wiener JM, Dulcan MK. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004, pp 557–573Google Scholar

13. Fairbanks JM, Pine DS, Tancer NK, Dummit ES III, Kentgen LM, Martin J, Asche BK, Klein RG: Open fluoxetine treatment of mixed anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1997; 7:17–29Google Scholar

14. Birmaher B, Waterman GS, Ryan N, Cully M, Balach L, Ingram J, Brodsky M: Fluoxetine for childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:993–999Google Scholar

15. The Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group: Fluvoxamine for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:1279–1285Google Scholar

16. Rynn MA, Siqueland L, Rickels K: Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of children with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:2008–2014Google Scholar

17. Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Monk K, Kalas C, Clark DB, Ehmann M, Bridge J, Heo J, Brent DA: Fluoxetine for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:415–423Google Scholar

18. Rickels K, Pollack MH, Sheehan DV, Haskins JT: Efficacy of extended-release venlafaxine in nondepressed outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:968–974Google Scholar

19. Gelenberg AJ, Lydiard RB, Rudolph RL, Aguiar L, Haskins JT, Salinas E: Efficacy of venlafaxine extended-release capsules in nondepressed outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000; 283:3082–3088Google Scholar

20. Chaput F, Fisher P, Klein R, Greenhill L, Shaffer D: The Columbia KSADS (Schedule for Affective DIsorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Divison of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1999Google Scholar

21. Puig-Antich J, Chambers WJ: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (KIDDIE-SADS). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

22. Poznanski EO, Freeman LN, Mokros HB: Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised. Psychopharmacol Bull 1985; 21:979–989Google Scholar

23. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

24. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:980–988Google Scholar

25. The Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS): development and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:1061–1069Google Scholar

26. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Google Scholar

27. Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, Neer SM: The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:545–553Google Scholar

28. Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M: Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1230–1236Google Scholar

29. Mallinckrodt CH, Raskin J, Wohlreich MM, Watkin JG, Detke MJ: The efficacy of duloxetine: a comprehensive summary of results from MMRM and LOCF_ANCOVA in eight clinical trials. BMC Psychiatry 2004; 4:26Google Scholar

30. Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine J, Frank A, Luborsky L, Onken LS, Muenz LR, Thase ME, Weiss RD, Gastfriend DR, Woody GE, Barber JP, Butler SF, Daley D, Salloum I, Bishop S, Najavits LM, Lis J, Mercer D, Griffin ML, Moras K, Beck AT: Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:493–502Google Scholar

31. Allgulander C, Hackett D, Salinas E: Venlafaxine extended release (ER) in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder: twenty-four-week placebo-controlled dose-ranging study. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 179:15–22Google Scholar

32. Ialongo N, Edelsohn G, Werthamer-Larsson L, Crockett L, Kellam S: The significance of self-reported anxious symptoms in first grade children: prediction to anxious symptoms and adaptive functioning in fifth grade. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:427–437Google Scholar

33. Davidson JR: Pharmacotherapy of generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 11):46–50Google Scholar

34. Masi G, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, Poli P, Bertini N, Milantoni L: Generalized anxiety disorder in referred children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43:752–760Google Scholar

35. Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Lowry R, Harris WA, McManus T, Chyen D, Collins J: Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2003. MMWR Surveill Summ 2004; 53:1–96Google Scholar

36. Kusiak V: Dear health care professional (letter on venlafaxine). Collegeville, Penn, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Aug 22, 2003Google Scholar

37. Hammad TA: Review and Evaluation of Clinical Data. Washington, DC, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Aug 16, 2004. Available at http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/04/briefing/2004-4065b1-10-TAB08-Hammads-Review.pdfGoogle Scholar