Childhood Psychiatric Disorders and Young Adult Crime: A Prospective, Population-Based Study

Abstract

Objective: While psychopathology is common in criminal populations, knowing more about what kinds of psychiatric disorders precede criminal behavior could be helpful in delineating at-risk children. The authors determined rates of juvenile psychiatric disorders in a sample of young adult offenders and then tested which childhood disorders best predicted young adult criminal status. Method: A representative sample of 1,420 children ages 9, 11, and 13 at intake were followed annually through age 16 for psychiatric disorders. Criminal offense status in young adulthood (ages 16 to 21) was ascertained through court records. Results: Thirty-one percent of the sample had one or more adult criminal charges. Overall, 51.4% of male young adult offenders and 43.6% of female offenders had a child psychiatric history. The population-attributable risk of criminality from childhood disorders was 20.6% for young adult female participants and 15.3% for male participants. Childhood psychiatric profiles predicted all levels of criminality. Severe/violent offenses were predicted by comorbid diagnostic groups that included both emotional and behavioral disorders. Conclusions: The authors found that children with specific patterns of psychopathology with and without conduct disorder were at risk of later criminality. Effective identification and treatment of children with such patterns may reduce later crime.

The prevalence of mental illness among persons involved with the juvenile and criminal justice systems is known to be particularly high (1 – 5) . For instance, in an ethnically diverse sample of 1,829 youths 10–18 years of age in juvenile detention, Teplin and colleagues (6 – 8) found that 6-month prevalence rates for any psychiatric disorder were 63.3% for boys and 71.2% for girls, three to four times higher than rates in general-population samples. In the same study, half of all juvenile detainees met criteria for a substance use disorder, and about a quarter had conduct disorder. Comorbidity rates for boys and girls were higher than those observed in community samples even after excluding conduct and substance use disorders—disorders whose symptoms overlap with criminal behavior. In general, studies of incarcerated or adjudicated youths find that girls have higher rates of both individual and comorbid psychiatric disorders than boys (1 , 3 , 4) . Although most of this difference is attributed to higher rates of affective and anxiety disorders (1 , 3 , 5) , in some studies, incarcerated or adjudicated girls have been found to have higher rates of conduct disorder than boys (4) .

Although such studies show that there is a strong link between criminal behavior and psychopathology, they are cross-sectional in design and do not indicate which disorders precede criminal behavior. Furthermore, data based on incarcerated youths, a highly selected sample, cannot tell us which children in the general population are at the highest risk of criminal behavior. Prospective studies point to hyperactivity (9 – 11) , conduct problems (12 – 17) , and early substance use (18 – 20) as predictors of later delinquency and criminal behavior. Conduct disorder and criminality overlap such that relations between conduct problems and later criminality may be attenuated when controlling for juvenile offending (21) . Hyperactivity appears to predict criminal behavior independent of conduct problems (21) but may best predict criminality when comorbid with conduct problems (22) . Despite the strong correlation between substance use and delinquency, substance use appears to predict criminal behavior only in children with early-onset and persistent substance use (18 , 23 , 24) . Many of these prospective studies have focused on high-risk samples of urban boys and measured broad indices of psychopathology rather than specific diagnoses. Other studies that used population-based samples with detailed assessments of psychiatric phenotypes did not test for the effects of various comorbidity profiles between emotional and behavioral disorders. Combinations of such disorders may be more specific indicators of the risk of criminality than single disorders.

In this study, we used data from a population-based, longitudinal sample followed from childhood to early adulthood (ages 16–21) to examine the relationships between a range of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders and young adult criminal offenses. Full psychiatric assessments were conducted in multiple waves using a well-validated structured interview that assesses all common childhood DSM-IV disorders. We looked backward to examine the burden of childhood psychiatric status in young adults with or without any criminal offense, then tested whether distinct childhood psychiatric profiles predict different young adult offense categories.

Method

Sample

The Great Smoky Mountains Study is a longitudinal representative study of psychiatric disorder, impairment, and service use in 11 predominantly rural counties of North Carolina (6 , 25) . The two-stage sampling design and methods have been described in detail elsewhere (26) . Briefly, a household equal-probability accelerated cohort design was used to recruit three cohorts of children, ages 9, 11, and 13 at intake, from a pool of some 20,000 children. The externalizing problems scale of the Child Behavior Checklist (27) was administered to a parent (usually the mother) of the first-stage sample (N=3,896) by telephone or in person. All children who scored above a predetermined cutpoint (the top 25% of the total scores), plus a 1-in-10 random sample of the rest (i.e., of the remaining 75% of the total scores), were recruited for detailed interviews. Ninety-five percent of families contacted completed the telephone screen. Of those recruited in this way, 80% (N=1,070) agreed to participate.

Approximately 8% of the area residents and the sample are African American, and fewer than 1% are Hispanic. American Indians make up only about 3% of the population of the study area but were oversampled to constitute 25% of the study sample by using the same screening procedure but recruiting everyone irrespective of screen score. Of the 456 Indian children identified, screens were obtained for 96%, and 81% (N=350) participated in the study, for a total sample of 1,420 participants. All participants were given a weight inversely proportional to their probability of selection, so that the results presented are representative of the population from which the sample was drawn.

Across annual assessments, 83% of the possible interviews were completed, with a range from 75% to 94% across each of the waves. This study draws on data from 6,674 parent-child pairs of interviews carried out when participants were in the age range of 9–16 years. Data were thus collected on one cohort at ages 9 and 10, on two cohorts at ages 11, 12, and 13, and on all three cohorts at ages 14, 15, and 16.

Procedure

Children and their primary caregiver were interviewed separately at home or at a convenient location by trained bachelor’s-level interviewers. Interviewers were local residents and received 1 month of training and constant monitoring for quality control. Before the interview began, parent and child signed informed consent or assent forms. Each parent and child was paid $10 for their participation.

Measures

Psychiatric disorders were assessed using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (28 – 30) . Symptoms were coded using an extensive glossary, and diagnoses were generated by computer algorithms. A symptom was counted as present if it was reported by either the parent or the child, as is standard clinical practice. Two-week test-retest reliability of diagnoses based on the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment in children 10–18 years of age is comparable to that of other highly structured interviews (kappa values for individual disorders range from 0.56 to 1.0) (29) . To minimize recall bias, the time frame of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment for determining the presence of most psychiatric symptoms is the 3 months immediately preceding the interview. For this study, we included any diagnosis for which the child met full diagnostic criteria by age 16; thus a child would be considered to have multiple disorders even if the disorders were not diagnosed concurrently.

A dichotomous poverty status variable using U.S. Census Bureau thresholds based on income and family size was coded according to whether the family met the Census Bureau poverty threshold at any of the assessment points (28.9% of families).

The outcome measure for all analyses was late adolescent and young adult arrest status, or arrests that occurred when the participant was between 16 and 21 years of age. In North Carolina all arrests after one’s 16th birthday are under the jurisdiction of the adult criminal justice system. Criminal histories were harvested through systematic searches of the public access database of the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts. The database covers charges in North Carolina, including those occurring on American Indian reservations. Juvenile court records were also retrieved from each of the 11 counties’ courthouses with the permission of the juvenile court judges.

Participants were categorized into four mutually exclusive groups according to the individual’s most serious charge: no offenses; minor offenses, such as disorderly conduct, trespass, and shoplifting; moderate offenses, which are primarily property crimes that do not involve serious harm to a person although the potential for harm may be present, such as simple assault, felony larceny, and drug-related offenses; and severe/violent offenses, which are primarily offenses involving violence against persons or significant potential for violence, such as sexual assault, armed robbery, and assault with a deadly weapon.

Data Analysis

In all analyses, measures of childhood psychiatric status (cumulative prevalence rate prior to age 16) preceded those of young adult criminal status (ages 16–21). Prospective associations between childhood psychiatric disorder status and young adult criminality were analyzed first. Next, models were used to test bivariate relations between individual and comorbid child psychiatric profiles and charges for minor, moderate, and severe/violent offenses. Finally, these bivariate models were retested with adjustment for poverty and juvenile justice status, two potential confounders of the relationship between childhood psychopathology and adult crime. All models tested for the presence of diagnosis-by-sex interaction effects.

All analyses used logistic regression with sampling weights to account for the two-phase sampling design, and robust variance estimates were generated using the generalized estimating equations approach implemented in SAS PROC GENMOD. Robust variance estimates (i.e., sandwich-type estimates), together with the sampling weights, were used to adjust the standard errors of the parameter estimates to take account of the multiphase sampling design. The prevalence estimates and comparison effects therefore reflect the population from which the sample was drawn.

Results

Descriptive Information

Of the total sample of 1,420 children, 473 (31.5% weighted) were arrested between ages 16 and 21. As expected, more males (42.8%) than females (19.6%) were arrested (odds ratio=3.1, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.1–4.6). Among those arrested, slightly more than half (N=241, 55.1%) were arrested for minor offenses, 26.7% (N=145) were arrested for moderate offenses, and about one in five (N=87, 18.3%) were arrested for severe/violent offenses. The total number of offenses per individual differed significantly across the arrest severity groups (z=10.8, p<0.001), with the mean rates ranging from 2.3 (SD=1.9) for the minor offense group to 10.5 (SD=15.3) for the moderate offense group and 15.1 (SD=18.9) for the severe/violent offense group. As expected, offense category was strongly predicted by male sex (minor offenses: odds ratio=2.5, 95% CI=1.8–3.3; moderate offenses: odds ratio=2.4, 95% CI=1.6–3.6; severe/violent offenses: odds ratio=14.0, 95% CI=6.4–30.3). Given the small number of females arrested for a severe/violent offense (N=13), these participants are grouped with the moderate female offenders in all further analyses. No between-groups differences in ethnicity were observed between whites and American Indians (minor offenses: odds ratio=0.8, 95% CI=0.5–1.1; moderate offenses: odds ratio=0.7, 95% CI=0.4–1.1; severe/violent offenses: odds ratio=0.8, 95% CI=0.4–1.3).

Childhood Psychiatric Disorders and Young Adulthood Arrest Status

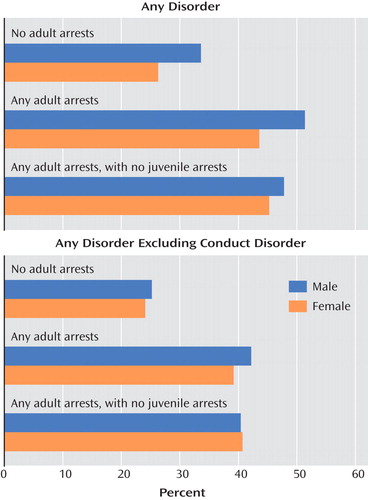

Figure 1 compares the prevalences of overall childhood diagnoses among those with no arrests, those with arrests in young adulthood (ages 16–21) only, and those with arrests as juveniles (through age 15) and in young adulthood. Cumulative rates of DSM-IV disorders for children (through age 16) with no young adult offenses were 33.6% (SE=3.7) for boys and 26.3% (SE=3.0) for girls, compared with rates of 51.4% (SE=4.6) for male offenders and 43.6% (SE=6.9) for female offenders (male offenders: odds ratio=2.2, 95% CI=1.1–4.1; female offenders: odds ratio=2.1, 95% CI=1.3–3.4). This discrepancy remained even in analyses controlling for juvenile history of criminality (male offenders: 47.8% versus 31.6%, odds ratio=2.0, 95% CI=1.1–3.4; female offenders: 45.3% versus 24.5%, odds ratio=2.6, 95% CI=1.3–5.2). The likelihood of an adult arrest was not higher for youths who had a juvenile criminal history in addition to a childhood psychiatric disorder than for those with a childhood psychiatric disorder and no juvenile criminal history.

Given the overlap between conduct problems and criminal behavior, the analyses were repeated with conduct disorder diagnoses excluded. As expected, the prevalence of childhood psychiatric disorders decreased across all arrest status groups, and more so for males than for females. However, childhood diagnoses other than conduct disorder remained significantly higher for participants who had been arrested in young adulthood, irrespective of whether they had also been arrested as juveniles (male offenders: 40.4% versus 23.4%, odds ratio=2.2, 95% CI=1.2–4.1; female offenders: 40.7% versus 22.4%, odds ratio=2.4, 95% CI=1.1–5.2).

We computed the population-attributable risk (31) of crime in this sample—that is, an estimate of the proportion of adult crime in this study that is attributable to child psychiatric disorder exposure: 19.5% of crime among females and 28.7% of crime among males in this study is attributable to juvenile mental disorders. Adjusted for juvenile justice status and conduct disorder, the population-attributable risk estimates for females and males are 20.6% and 15.3%, respectively.

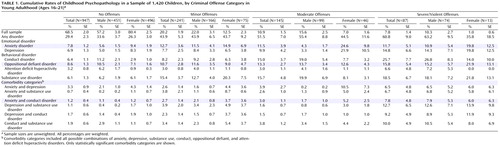

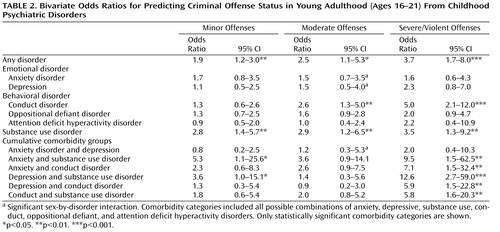

Table 1 presents the cumulative prevalence rates of single diagnoses and common comorbid diagnostic categories for each arrest group. Cumulative comorbid diagnostic groups were derived by determining whether children met diagnostic criteria for more than one disorder during their time in the study (not necessarily at the same time point). Table 2 presents the odds ratios for the associations between childhood psychiatric disorders and criminal offense status in young adulthood, comparing those who had not been arrested with those who had been arrested for minor, moderate, and severe/violent offenses in separate analyses.

Only psychiatric histories involving a substance use disorder, either alone or comorbid with another psychiatric disorder, predicted subsequent arrest for minor offenses in young adulthood. While arrests for both moderate and severe/violent offenses were predicted by conduct and substance use disorder, arrest for severe/violent offenses was also predicted by comorbidity groupings involving conduct disorder, substance disorder, and emotional disorders.

Sex-by-diagnosis interactions were tested for each disorder, and few were statistically significant. All significant sex differences were observed for associations between emotional disorders and moderate offenses. For male participants, emotional disorders did not predict arrest for moderate offenses (anxiety disorders: odds ratio=0.7, 95% CI=0.3–2.0; depressive disorders: odds ratio=0.6, 95% CI=0.2–1.8), nor did they predict lower offense status (comorbid anxiety and depressive disorder: odds ratio=0.1, 95% CI=0.1–0.8). For female participants, in contrast, comorbid anxiety and depression did not predict offense status (odds ratio=2.6, 95% CI=0.5–13.9), but depressive disorders showed a nonsignificant trend toward predicting offense status (odds ratio=3.1, 95% CI=0.9–11.4, p=0.08) and anxiety disorders significantly predicted arrest for moderate offenses (odds ratio=3.1, 95% CI=1.0–9.6).

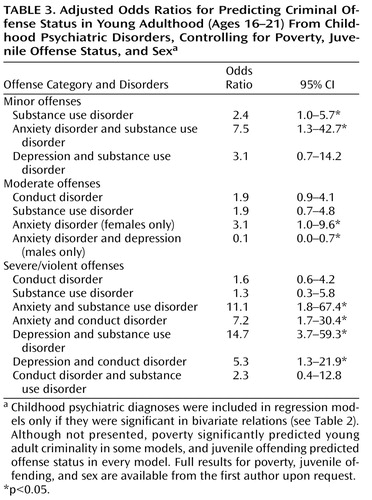

Finally, we examined the association between each childhood psychiatric diagnosis and young adult criminality, controlling for two childhood variables that have been shown to have an effect on offense status—poverty and juvenile arrest status. Sex was also treated as a covariate because of differences in rates of disorders and offense groups between males and females. Childhood psychiatric disorders that were significantly related to young adult offense status in the bivariate analyses (see Table 2 ) were retested, including the control variables. In the few cases in which sex-by-disorder interactions were observed, models were tested separately by sex.

As Table 3 shows, psychiatric predictors differed by offense group and by sex. Two of three bivariate predictors continued to predict minor offense status, and both involved substance use disorders. Moderate offense status was predicted only by emotional disorders, but the effect of these disorders was sex specific: in females, childhood anxiety was a risk factor, and in males, childhood anxiety and depression were protective factors. Four of seven possible bivariate predictor combinations predicted severe/violent offenses, and each involved a comorbid group. While conduct and substance use disorders were involved in each significant predictor of severe/violent offenses, neither conduct nor substance use disorders alone was a predictor.

Discussion

Nearly half of the young adults with a criminal record in our sample had a history of mental illness, as compared with one in three male or one in four female young adults with no criminal history. This rate was only slightly lower among young adults who had no involvement with the juvenile justice system, and the added risk of childhood psychopathology for young adult criminality remained after analyses controlled for childhood conduct disorder. That this effect remained after controlling for conduct disorder is consistent with findings from studies of community and juvenile detention samples suggesting that conduct disorder rarely occurs alone (3 , 32) . After appropriate controls were applied, 20.6% of female crime and 15.3% of male crime in this study was attributable to childhood mental disorders. This is a substantial level of attributable risk; consider, for instance, that the population-attributable risk of myocardial infarction from being overweight (body mass index >25) is only around 11% (33) .

Psychiatric profiles were identified for all offense groups; they all included conduct and/or substance use disorders, but some also involved emotional disorders, such as anxiety and depression. After analyses controlled for childhood poverty status and juvenile justice status, severe/violent offender status was predicted by four comorbid profiles: anxiety and substance use disorders; anxiety and conduct disorders; depression and substance use disorders; and depression and conduct disorder. While both conduct and substance problems have been shown to predict criminality and violence, neither disorder alone predicted arrest for the serious/violent offenses after controlling for poverty status, juvenile justice status, and sex. This suggests that the patterns of risk associated with these disorders are more specific than in previous findings.

Moderate offenses include a range of property crimes and offenses involving possession of illicit substances, yet the only significant diagnostic risk factor was anxiety disorder status in females. There was some evidence that emotional disorders serve as a protective factor against moderate offense status for males, but not for females. Further research to retest this effect will need to pay careful attention to the issues of comorbidity and seriousness of offenses. The least serious offenses were predicted by substance use, alone or comorbid with anxiety disorders.

Our findings are consistent with other studies that have identified the important roles of conduct and substance disorders in later criminality (9 , 24 , 34) , yet all but one significant psychiatric profile association in our study (substance use disorders with minor offenses) involved either an anxiety or a depressive disorder. This observation supplements the conclusions of some studies of high-risk youths that have focused primarily on behavioral and substance use disorders. Our study also suggests an almost pervasive role for comorbid behavioral and emotional disorders in understanding the risk of criminality and a more limited role for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. To some extent, these discrepancies are not surprising, given the differences between high-risk and population samples (32) . Fortunately, a number of representative longitudinal studies have collected the information on psychiatric and criminal functioning necessary to retest our findings. In some cases, these studies looked at a wide range of risk factors associated with criminality without focusing primary attention on the role of childhood psychopathology. Our findings strongly support assessment of DSM-IV disorders (including cumulative comorbidity) in future studies of criminal risk.

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

The study participants lived in a rural area, and the study oversampled for American Indian children, with very few African Americans (8%) and no Latinos or Asian Americans. Thus, the sample is far from representative of the U.S. population. Comparison of the Great Smoky Mountains Study with other studies indicates similar rates of cumulative childhood disorders in representative samples from other counties, other regions of the United States, and samples involving greater proportions of Hispanic and African American youths (35) . Studies of detained and incarcerated youths generally find higher levels of psychopathology in non-Hispanic white youths than in African-American and Hispanic youths (3 , 5) . It will be important in future research to test racial/ethnic differences in rates of psychopathology and criminality and associated risk models in community samples.

Although rural crime rates, particularly for violent crime, tend to be lower than in urban areas (36) , crime trends and correlates of criminal behavior are similar in rural and urban areas (37 , 38) . For example, social disorganization, a primary construct in criminologists’ understanding of urban crime, was also implicated in a recent five-state study of rural crime in which residential instability, ethnic diversity, and family disruption predicted violent crime to the same degree as in urban samples (38) . While these findings require replication, they suggest that there are fewer differences between urban and rural correlates of criminality than is sometimes supposed.

In this study, criminal activity in young adulthood was coded from official arrest data rather than self-reports of offending behaviors. Use of official records is most likely to have a conservative effect on the analyses by underestimating criminal activity, since not all crimes lead to arrest. Juvenile arrests and young adult arrests that occurred in other states or countries were not identified in this study. Another limitation in the focus on arrests is that some of the alleged offenses may not have occurred. Arrest data are, however, preferable to conviction data for analyses, because conviction status is often contingent on circumstances unrelated to the criminal event, such as the offender’s prior criminal history and willingness to admit guilt, as well as the standards of the local criminal justice system.

Clinical Implications

Clinicians are already attentive to the risk of criminal activity in youths with conduct disorder, and our results support this stance. However, psychiatric diagnoses other than conduct disorder, particularly when comorbid with conduct or substance use disorders, may also indicate an increased risk of subsequent criminality. Both male and female participants with childhood psychiatric disorders other than conduct disorder were twice as likely to be involved with the criminal justice system as young adults than those with no childhood disorder, and their criminal activity is far from insignificant, with risk concentrated on the most serious forms of offending. Particular attention should be paid to youths with a history of multiple diagnoses, even if they did not occur simultaneously.

If childhood psychiatric status is, as this study suggests, a common risk factor for criminality, effective treatment of childhood psychiatric disturbance may reduce the subsequent burden on the criminal justice system. Childhood treatment may also be cost-effective: a recent study estimated average annual mental health service costs across seven service sectors at $4,500 to $7,000 for children with diagnosable disorders (39) , whereas the direct costs of adult incarceration are approximately $23,000 a year in federal facilities (40) . Yet less than half of children with multiple psychiatric disorders receive any mental health services (39) .

The mental health and criminal justice systems would both benefit from improved identification and treatment of children with psychiatric disorders. However, addressing the mental health needs of children and adolescents would not alone be sufficient to divert all young adults from criminal activity. More than half of those in our sample who had a criminal record in young adulthood had no history of childhood psychopathology, and most participants with a childhood diagnosis did not get arrested in young adulthood. This suggests that childhood psychiatric status may mark only one of various paths to criminality.

1. Wasserman GA, McReynolds LS, Ko SJ, Katz LM, Carpenter JR: Gender differences in psychiatric disorders at juvenile probation intake. Am J Public Health 2005; 95:131–137Google Scholar

2. Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK: Comorbid psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:1097–1108Google Scholar

3. Teplin L, Abrah K, McClelland G, Dulcan M, Mericle A: Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:1133–1143Google Scholar

4. McCabe KM, Lansing AE, Garland A, Hough RL: Gender difference in psychopathology, functional impairment and familial risk factors among adjudicated delinquents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:860–867Google Scholar

5. Domalanta D, Risser W, Roberts R, Risser J: Prevalence of depression and other psychiatric disorders among incarcerated youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:477–484Google Scholar

6. Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A: Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:837–844Google Scholar

7. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, Davies M, Piacentini J, Schwab-Stone ME, Lahey BB, Bourdon K, Jensen PS, Bird HR, Canino G, Regier DA.: The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA Study: methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:865–877Google Scholar

8. Angold A, Erkanli A, Farmer EMZ, Fairbank JA, Burns BJ, Keeler G, Costello EJ: Psychiatric disorder, impairment, and service use in rural African American and white youth. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:893–901Google Scholar

9. Magnusson D, af Klinteberg B, Stattin H: Juvenile and persistent offenders: behavioral and physiological characteristics, in Adolescent Problem Behaviors: Issues and Research. Edited by Ketterlinus RD, Lamb ME. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1994, pp 81–91Google Scholar

10. Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffitt T, Wikström P-O, Loeber R, Novak S: The interaction between impulsivity and neighborhood context on offending: the effects of impulsivity are stronger in poorer neighborhoods. J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 109:563–574Google Scholar

11. Loeber R, Brinthaupt VP, Green SM: Attention deficits, impulsivity, and hyperactivity with or without conduct problems: relationships to delinquency and unique contextual factors, in Behavior Disorders of Adolescence: Research, Intervention, and Policy in Clinical and School Settings. Edited by McMahon RJ, Peters RD. New York, Plenum Press, 1990, pp 39–61Google Scholar

12. Loeber R: Developmental continuity, change, and pathways in male juvenile problem behaviors and delinquency, in Delinquency and Crime: Current Theories. Edited by Hawkins D. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp 1–27Google Scholar

13. Loeber R: Development and risk factors of juvenile antisocial behavior and delinquency. Clin Psychol Rev 1990; 10:1–41Google Scholar

14. Stattin H, Magnusson D: The role of early aggressive behavior in the frequency, seriousness, and types of later crime. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989; 57:710–718Google Scholar

15. Farrington DP: Conduct disorder and delinquency, in Risks and Outcomes in Developmental Psychopathology. Edited by Steinhausen HC, Verhulst FC. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999, pp 165–192Google Scholar

16. Nagin D, Tremblay RE: Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Dev 1999; 70:1181–1196Google Scholar

17. Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB: Multiple risk factors for multiproblem boys: co-occurrence of delinquency, substance use, attention deficit, conduct problems, physical aggression, covert behavior, depressed mood, and shy/withdrawn behavior, in New Perspectives on Adolescent Risk Behavior. Edited by Jessor R. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp 91–149Google Scholar

18. Van Kammen WB, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M: Substance use and its relationship to conduct problems and delinquency in young boys. J Youth Adolesc 1991; 20:399–413Google Scholar

19. Loeber R: Natural histories of conduct problems, delinquency, and associated substance use: evidence for developmental progressions, in Advances in Clinical Child Psychology, vol 11. Edited by Lahey BB, Kazdin AE. New York, Plenum Press, 1988, pp 73–125Google Scholar

20. Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Menard S: Multiple Problem Youth: Delinquency, Substance Use, and Mental Health Problems. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1988Google Scholar

21. Elander J, Simonoff E, Pickles A, Holmshaw J, Rutter M: A longitudinal study of adolescent and adult conviction rates among children referred to psychiatric services for behavioral and emotional problems. Crim Behav Ment Health 2000; 10:40–59Google Scholar

22. Lynam DR: Early identification of the fledgling psychopath: locating the psychopathic child in the current nomenclature. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107:566–575Google Scholar

23. Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, White HR: Developmental aspects of delinquency and internalizing problems and their association with persistent juvenile substance use between ages 7 and 18. J Clin Child Psychol 1999; 28:322–332Google Scholar

24. Farrington DP: Early predictors of adolescent aggression and adult violence. Violence Victims 1989; 4:79–100Google Scholar

25. Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Stangl DK, Tweed DL, Erkanli A, Worthman CM: The Great Smoky Mountains Study of youth: goals, designs, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1129–1136Google Scholar

26. Schaie KW: A general model for the study of developmental problems. Psychol Bull 1965; 64:92–107Google Scholar

27. Achenbach TM: Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

28. Angold A, Costello EJ: The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:39–48Google Scholar

29. Angold A, Costello EJ: A test-retest reliability study of child-reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA-C). Psychol Med 1995; 25:755–762Google Scholar

30. Angold A, Cox A, Prendergast M, Rutter M, Simonoff E, Costello EJ, Ascher BH: The Young Adult Psychiatric Assessment (YAPA). Durham, NC, Duke University Medical Center, 1999Google Scholar

31. Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1998Google Scholar

32. Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A: Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999; 40:57–87Google Scholar

33. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Bautistia L, Franzosi M, Commerford P, Lang C, Rumboldt Z, Onen C, Lisheng L, Tanomsup S, Wangai P, Razak F, Sharma A, Anand S: Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet 2005; 366:1640–1649Google Scholar

34. Huizinga D, Jakob-Chien C: The contemporaneous co-occurrence of SVJ offending and other problem behaviors, in Never Too Early, Never Too Late: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions for Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders. Edited by Loeber R, Farrington DP. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage Publications, 1997Google Scholar

35. Jaffee S, Harrington H, Cohen P, Moffitt TE: Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorder in youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:406–407Google Scholar

36. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Urban, Suburban, and Rural Victimization, 1993–1998. Washington, DC, Department of Justice, 2000Google Scholar

37. Laub JH: Patterns of offending in urban and rural areas. J Criminal Justice 1983; 11:129–142Google Scholar

38. Osgood DW, Chambers JM: Community correlates of rural youth violence. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, May 2003Google Scholar

39. Costello EJ, Copeland W, Cowell A, Keeler G: Service costs of caring for adolescents with mental illness in a rural community, 1993–2000. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:36–42Google Scholar

40. Federal Bureau of Prisons: Key Indicators/Strategic Support System. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, October 1997Google Scholar