Impact of Trait Impulsivity and State Aggression on Divalproex Versus Placebo Response in Borderline Personality Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to determine whether specific pretreatment clinical characteristics differentially predict favorable treatment response to divalproex versus placebo for impulsive aggression in patients with borderline personality disorder. METHOD: Fifty-two outpatients with DSM-IV borderline personality disorder were randomly assigned to receive divalproex (N=20) or placebo (N=32), double-blind, for 12 weeks. Trait impulsivity symptoms were determined by using the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, and state aggression symptoms were determined by using the Overt Aggression Scale modified for outpatients. Affective stability was determined by using the Young Mania Rating Scale and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Analyses were performed to identify possible baseline symptom domains that predict treatment response. RESULTS: Divalproex was superior to placebo in reducing impulsive aggression in patients with borderline personality disorder. Divalproex-treated patients responded better than placebo-treated patients among those with higher baseline trait impulsivity symptoms and state aggression symptoms. The effects of baseline trait impulsivity and state aggression appear to be independent of one another. However, baseline affective instability did not influence differential treatment response. CONCLUSIONS: Both pretreatment trait impulsivity symptoms and state aggression symptoms predict a favorable response to divalproex relative to placebo for impulsive aggression in patients with borderline personality disorder.

Borderline personality disorder is a heterogeneous and potentially severe disorder that is associated with impairments across many symptom areas as well as greater risk of substance abuse, suicide, and other morbidities. Affective instability and impulsive aggression are hallmarks of borderline personality disorder and are targets for treatment (1). We previously reported the results of a large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study examining the efficacy and safety of divalproex in reducing impulsive aggression across psychiatric diagnoses (2), presenting preliminary evidence that divalproex ameliorated impulsive aggression, irritability, and global severity in patients with Cluster B personality disorders. This article examines pretreatment clinical characteristics that might predict treatment response for impulsive aggression in patients with borderline personality disorder.

Method

This study has been described in detail elsewhere (2). Eligible patients, as defined in the next paragraph, were randomly assigned to receive either divalproex sodium or matching placebo for 12 weeks.

Patients 18–65 years old with cluster B personality disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosed by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV were eligible for inclusion in the original study. Patients had a history of aggression (two episodes of physical or verbal aggressive outbursts per week, on average, for at least the month preceding screening, which caused marked distress or impairment in occupational or interpersonal function). A score of 15 or higher on the aggression scale of the Overt Aggression Scale modified for outpatients (3, 4) was required at the first screening visit and at least one additional visit before random assignment to treatment groups. Exclusion criteria included lifetime bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder with hypomania in the past year, baseline Young Mania Rating Scale score (5) of 12 or higher, major depressive disorder of significant severity (score greater than 15 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale), history of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, symptoms of dementia, serious homicidal or suicidal ideation, or impulsive aggression caused by previous head trauma or other medical conditions.

The Overt Aggression Scale was conducted at baseline and weekly thereafter, with telephone visits at weeks 5 and 7.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Baseline comparability between the treatment groups for demographic characteristics was assessed by one-way analysis of variance with treatment group as the main effect for quantitative variables and by Fisher’s exact test, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, or Wilcoxon rank sums test, as appropriate.

The primary efficacy measure was change in Overt Aggression Scale aggression score over the treatment interval. Efficacy analyses were performed with an intent-to-treat data set, which included all patients who received at least one dose of study drug and had at least one Overt Aggression Scale rating while receiving the drug. The effects on the Overt Aggression Scale aggression score of baseline Young Mania Rating Scale score, baseline Barratt Impulsiveness Scale total score (6), baseline Overt Aggression Scale aggression score, baseline Aggression Questionnaire (7) score, and baseline Hamilton depression scale total score during the study were assessed by using a median split of each of these variables. Drug effect (divalproex versus placebo), subgroup effect (patients with scores ≤ median value versus those with scores > median value on each measure), and the interaction between drug and subgroup were analyzed by using repeated-measures analysis of covariance; when the interaction was significant, the data were reanalyzed for each subgroup separately to compare the two treatments. Since the data were skewed, analyses were also performed with the square-root-transformed aggression scores on the Overt Aggression Scale. Because results from both transformed and untransformed data were robust, results from analyses of untransformed data are presented in this article.

The correlation between baseline total score on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale and aggression score on the Overt Aggression Scale was determined by using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results

Fifty-two patients with borderline personality disorder were randomly assigned to treatment with divalproex or placebo and received at least one dose of the study drug. There were 20 patients in the divalproex group (mean modal dose=1325 mg/day; range=500–2250) and 32 patients in the placebo group. Of the 52 patients who received the study drug, 50 patients (18 in the divalproex group and 32 patients in the placebo group) were included in intent-to-treat analyses of efficacy.

The treatment groups were similar at baseline in demographic characteristics, history of major depressive disorder, number of past psychiatric hospitalizations, and histories of addictive behavior and prosecution (Table 1). The mean age of the intent-to-treat study group was 34.3 years (SD=10.1), 43 (86%) were Caucasian, 27 (54%) were female, 19 (38%) had a history of major depression, and 10 (20%) had previous psychiatric hospitalization(s). Previous histories of alcohol (14 [28%] of the patients) and other drug abuse/dependence (eight [16%] of the patients) were also reported. About half (N=23 [46%]) had been arrested. The median baseline aggression score on the Overt Aggression Scale was 33.5 (mean=53.5) for patients in the divalproex group and 35.2 (mean=52.8) for patients in the placebo group; there was no significant difference between treatment groups.

In the analysis of mean change in aggression score from baseline, a statistically significant drug effect was observed when baseline Young Mania Rating Scale score (0 versus >0) was used as a covariate as well as when baseline Hamilton depression scale score (≤8.5 versus >8.5) was used as a covariate (Table 2). When response was analyzed with baseline Aggression Questionnaire score as a covariate, drug effect approached the level of statistical significance (p<0.06). A statistically significant drug effect without a significant drug-by-subgroup interaction indicates that divalproex was superior to placebo in both subgroups of patients (≤ median value, > median value).

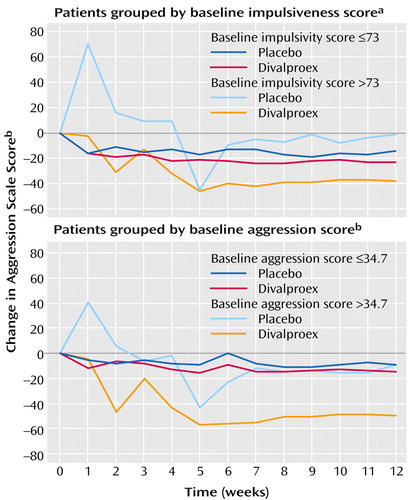

A statistically significant drug-by-subgroup interaction was seen when mean change from baseline aggression score on the Overt Aggression Scale was analyzed with baseline Barratt Impulsiveness Scale total score (≤73 versus >73) as a covariate (Figure 1). When the data were reanalyzed for each subgroup separately, there was no difference between treatment groups in response among the patients with lower baseline impulsivity scores; however, divalproex-treated patients responded significantly better than the placebo-treated patients among those with higher baseline impulsivity scores.

When response was analyzed with baseline aggression score (≤34.7 versus >34.7) as a covariate, the drug-by-subgroup interaction approached the level of statistical significance (Figure 1) (p<0.06) A treatment effect was observed among patients with higher baseline aggression scores but not among those with lower scores.

There was poor correlation between baseline Barratt Impulsiveness Scale total score and baseline total score on the Overt Aggression Scale (r=0.21).

Discussion

Our data suggest that the presence of both trait impulsivity (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale) and state aggression (Overt Aggression Scale) symptoms, but not trait aggression (Aggression Questionnaire) symptoms, influence the antiaggressive response to divalproex in patients with borderline personality disorder and prominent histories of impulsive aggressiveness. The effects of impulsivity (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale) and aggression (Overt Aggression Scale) on treatment response appear to be independent of one another. The lack of correlation between scores on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale and the Overt Aggression Scale probably results from the fact that the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale is a trait measure and the Overt Aggression Scale is by definition state-dependent. In contrast, baseline affective instability, determined by measures of hypomania and depression (Young Mania Rating Scale, Hamilton depression scale), did not influence differential treatment response. These findings complement reports suggesting the possibility that divalproex (8), but not fluoxetine (9), may be preferentially efficacious in highly aggressive personality disordered individuals.

That specific affective symptoms (Hamilton depression scale depression, Young Mania Rating Scale mania) did not influence treatment outcome with divalproex suggests a direct antiaggressive effect rather than one mediated by improvement in affective instability. One must be mindful of the limitations of secondary analyses (e.g., small number of subjects). Nevertheless, these data may be helpful in identifying patient subgroups (e.g., those with high levels of state aggression or trait impulsivity) or baseline characteristics of borderline personality disorder that would guide future trials of mood stabilizers. These data may also affect the way we conceptualize borderline personality disorder, which appears to be characterized by independent symptom domains that are amenable to treatment.

|

|

Received Dec. 30, 2003; revision received April 19, 2004; accepted May 14, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Chicago/Pritzker School of Medicine; and Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Ill. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Hollander, Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1 Gustave L. Levy Place, Box 1230, New York, NY 10029-6574; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Ill.

Figure 1. Impact of Pretreatment Impulsiveness and Aggression Scores on Change in Aggression Scores of 50 Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder After Receiving Placebo or Divalproex Sodium for 12 Weeks

aTotal score on Barratt Impulsiveness Scale.

bAggression scale score on Overt Aggression Scale modified for outpatients.

1. Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, New AS, Goodman M, Silverman J, Serby M, Schopick F, Siever LJ: Are the interpersonal and identity disturbances in the borderline personality disorder criteria linked to the traits of affective instability and impulsivity? J Personal Disord 2001; 15:358–370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hollander E, Tracy KA, Swann AC, Coccaro EF, McElroy SL, Wozniak P, Sommerville KW, Nemeroff CB: Divalproex in the treatment of impulsive aggression: efficacy in cluster B personality disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:1186–1197Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Coccaro EF, Harvey PH, Kupshaw-Lawrence E, Herbert JL, Bernstein DP: Development of neuropharmacologically based behavioral assessments of impulsive aggressive behavior. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3(suppl 2):44–51Google Scholar

4. Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, Endicott J, Williams D: The Overt Aggression Scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:35–39Link, Google Scholar

5. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429–435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES: Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J Clin Psychol 1995; 51:768–774Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Buss AH, Perry M: The Aggression Questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol 1992; 63:452–459Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kavoussi RK, Coccaro EF: Divalproex sodium for impulsive aggressive behavior in patients with personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:676–680Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lee R, Coccaro EF: Treatment of aggression: serotonergic agents, in Aggression: Psychiatric Assessment and Treatment. Edited by Coccaro EF. New York, Marcel Dekker, 2003, pp 351–367Google Scholar