Disabilities, Quality of Life, and Mental Disorders Associated With Smoking and Nicotine Dependence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Epidemiological studies have reported an association between smoking and mental disorders. However, little is known about the impairment associated with nicotine dependence. METHOD: The authors assessed health-related quality of life, disability, and psychiatric comorbidity in adults with and without nicotine dependence. The analysis was based on data from 3,293 respondents, ages 18 to 65, from the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey, a nationally representative multistage probability survey conducted from 1997 to 1999. The authors assessed rates of smoking and health-related quality of life (Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey) by questionnaires. Nicotine dependence and other mental disorders were assessed with a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. RESULTS: The population prevalence of current smoking was 36.2% and the 1-year prevalence of nicotine dependence was 9.4%. Nicotine-dependent smokers reported a poorer quality of life than the subjects without nicotine dependence. These relationships were stable after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics. More than half of the subjects with nicotine dependence fulfilled criteria for at least one other mental disorder. Subjects suffering from nicotine dependence reported greater disability in the last month and in the last year. CONCLUSIONS: Smokers with nicotine dependence should be distinguished from other smokers in evaluations of the health status of populations.

Smoking is now well established as a recognized cause of cancer, lung disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke; it is considered the single most important avoidable cause of premature morbidity and mortality in the world (1, 2). Additionally, epidemiological studies have reported positive associations between smoking and psychiatric disorders (3, 4). Several studies have found high rates of smoking among selected populations of persons with mental illness (5, 6), whereas general population surveys have demonstrated a significant association between current smoking and psychiatric symptoms (7, 8). Lasser et al. (9) showed that persons with mental illness are about twice as likely to smoke as other persons on the basis of population data from the National Comorbidity Survey. The relationship between smoking and mental disorders has been the focus of considerable research, although little is known about the epidemiology of nicotine dependence, a disorder included in various psychiatric diagnostic criteria, such as in DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, and ICD-10.

However, nicotine dependence is in some respects an anomaly among psychiatric disorders. Although nicotine dependence causes more death and disability than all the other drug disorders combined (10), physicians and psychiatrists rarely cite this fact and underuse the diagnosis. On the other hand, nicotine dependence is a condition that is often discussed by the media; laypersons tend to overuse the diagnosis, assuming that all daily smokers are nicotine dependent (11). In a recent article, Breslau et al. (12) evaluated nicotine dependence in the United States. The authors found that younger adults were less likely to ever smoke daily, but those who did smoke daily had the highest risk of becoming dependent, compared with older subjects. Following their results, research should assess nicotine dependence rather than focusing on rates of smoking alone.

Although it is well known that smoking is a risk factor for poor health, we know of no recent study that has analyzed the association between nicotine dependence and functional impairment in a nationally representative sample. We hypothesized that nicotine dependence is not only a risk factor but is also associated with low health-related quality of life and high psychiatric comorbidity. We used population-based data from the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey (13, 14) to examine the association between nicotine dependence, health-related quality of life, disability, and associated psychiatric disorders.

Method

Data Sources

The German National Health Interview and Examination Survey is based on a stratified, multistage, cross-sectional, national representative sample of individuals ages 18 to 79 from the noninstitutionalized population of Germany (13–15). The survey was conducted by the German Ministry of Science to provide comprehensive data regarding physical and mental conditions and other health-related issues. Data collection occurred from October 1997 to March 1999. The interviews and examinations were carried out in two parts. The main survey consisted of a comprehensive health status examination conducted by a physician; respondents completed a self-administered questionnaire that included, among others, questions regarding quality of life, psychological and physical symptoms, and health conditions (a list of 43 diseases). Chronic illness was assessed in the present study by a response of “yes” or “no” to the question, “Do you have or did you ever have the following diseases: hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, asthma, or cancer?”

In addition to the main survey, the mental health supplement gathered data regarding a range of psychiatric disorders on the basis of a structured, clinical psychopathological interview.

The German National Health Interview and Examination Survey had 7,124 participants, the overall rate of response in the main survey was 61.5%, and the rate of response in the second stage (the psychiatric interview included 4,181 persons) was 87.6%. Nonresponse was mainly due to refusal to participate and an inability to reach selected respondents. The rates of nonresponse did not differ significantly between screen-negative and screen-positive respondents from the main survey (15).

Data were weighted by demographic characteristics (age, gender, and geographical location) and by selection probabilities (screen-negatives received twice the weight of screen-positives).

Assessment

The survey used a two-stage design for the identification of mental disorders. At the first stage, all participants completed the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (16) for mental disorders. Subjects ages 65 years and younger who screened positive and a 50% random sample of those who screened negative were selected for stage 2 of the survey, in which 4,181 participants were administered the full Composite International Diagnostic Interview (16) for DSM-IV disorders by clinical interviewers. Main survey participants ages 66 years and older were excluded from the mental health supplement because the psychometric properties of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview had not yet been satisfactorily established for use in older populations (17). The mental health interviews took place within 2 weeks of the main survey. The test-retest reliability of Composite International Diagnostic Interview was found to be acceptable. Diagnoses were made without diagnostic hierarchy rules, meaning that individuals could meet criteria for any disorder, regardless of the presence of other disorders.

The diagnoses in the present study included affective disorders (major depression, dysthymia, mania, and bipolar disorders), anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, simple phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder), substance abuse/dependence disorders (alcohol and drug abuse and dependence without nicotine dependence), and nicotine dependence. We analyzed persons with and without any mental illness in the last year and the last month (12-month prevalence and 1-month prevalence) and persons with each of the individual diagnoses and with multiple diagnoses.

We defined respondents as nonsmokers if they gave a negative response to the question, “Have you ever smoked?” We defined current smokers as those who responded “daily” or “some days” when they were asked, “Do you now smoke every day or some days?”

Persons who had ever smoked were then asked questions regarding the average number of cigarettes, cigars, or pipes of tobacco they smoked per day and the age at which they had started smoking. Former smokers were excluded from our analyses.

Three different categories were used to categorize nonsmokers, current smokers (without a 12-month diagnosis of nicotine dependence), and dependent smokers (with a 12-month diagnosis of nicotine dependence).

Health-related quality-of-life domains were measured with the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (18). This generic health measure is a self-administered 36-item questionnaire comprising eight health dimensions: bodily pain, physical function, role limitations related to physical health (physical role function), mental health, role limitations related to emotional health (emotional role function), social functioning, vitality, and general health, as well as two summary measures: physical component summary and mental component summary. In the present study, subscale scores were calculated according to standard procedures.

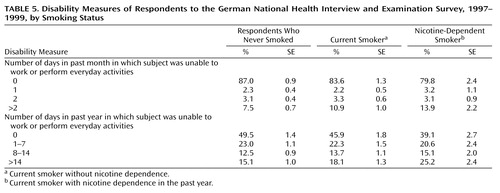

To assess disability and reduction in work productivity, the respondents were asked how many days in the last year and in the last month they were unable to work or to carry out normal, everyday activities.

All subjects voluntarily participated in the study. After a complete description of the study was provided, written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The data were released for public use in 2000 (19, 20).

Statistical Methods

We assessed the effect of smoking status on health-related quality of life by using analysis of variance; p values were computed by means of F statistics. The Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for trend was used to assess the association of smoking status with ordered categories of disability.

Multiple linear regression models were used to evaluate relationships between smoking status and health-related quality of life and to evaluate whether any observed effects were altered by sociodemographic characteristics. The dependent variables were the summary scores from the Short-Form Health Survey. The independent variables were smoking status, sociodemographic variables (sex, age, socioeconomic status, and marital status), and chronic illness.

Fit of the model was assessed by means of the R2 value, and the significance of each independent variable was assessed with the t test for the variable. Interactions between age, sex, and nicotine dependence were tested in each model. A two-tailed p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Analyses were performed by use of Stata (version 7.0) software (21), which includes commands for the analysis of complex survey data (survey commands incorporate the weighting and clustering of data).

Results

Of 4,181 participants examined in the mental health supplement, 60 subjects had missing values for self-rated smoking status. Most of the smokers in our study used cigarettes exclusively, whereas only 4% of the smokers were current cigar or pipe smokers. The lifetime prevalence of smoking in the sample was 56.3% and of DSM-IV nicotine dependence, 15.6%. The population prevalence of current smoking was 36.2% and of current (12-month) DSM-IV nicotine dependence, 9.4%. Men were more likely than women to be current smokers (39.8% and 32.6%, respectively), whereas there was no significant sex difference in the prevalence of nicotine dependence.

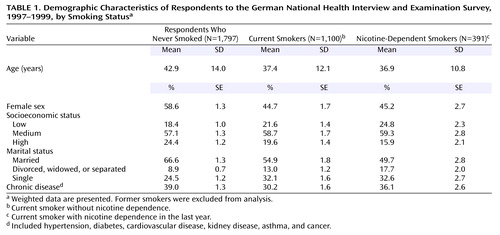

In the following analyses, we excluded data from former smokers (N=828), leaving 3,293 (weighted sample=3,288) participants. The demographic characteristics of the nonsmokers, current smokers, and dependent smokers are shown in Table 1. In comparison with nonsmokers, the subjects with nicotine dependence were younger, more often single, and of a lower socioeconomic status. Current smokers without nicotine dependence had a mean peak consumption of 14.1 (SD=9.8) cigarettes per day versus 20.4 (SD=10.4) for those with nicotine dependence in the last year. The onset of smoking occurred almost entirely before age 30 (95.5% of current smokers and 98.8% of dependent smokers).

There were significantly more subjects with chronic illness among the nonsmokers than among the nondependent current smokers. But no statistically significant difference was found between the nonsmokers and the nicotine-dependent smokers in the prevalence of chronic diseases.

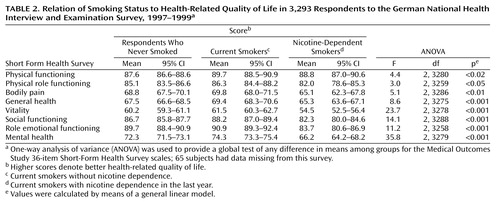

Table 2 presents the scores for health-related quality of life with respect to smoking status. We found a different pattern of quality-of-life scores among the three groups. With one exception, the dependent smokers reported poorer quality of life on all dimensions than the subjects without nicotine dependence. The largest differences were found for the mental dimensions of health status. However, the differences between the nonsmokers and the current nondependent smokers were quite small.

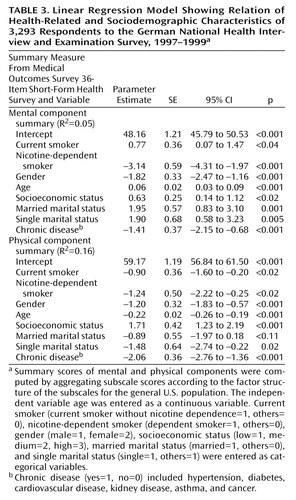

To explore further the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on smoking status and quality of life, we used linear regression modeling. The physical and mental component summaries of the Short-Form Health Survey were used as dependent variables in separate models to examine whether sociodemographic characteristics might explain the differences in health-related quality of life between nonsmokers, current smokers, and dependent smokers. After we controlled for age, gender, socioeconomic status, marital status, and chronic illness, nicotine dependence remained a significant predictor of health-related quality of life, as measured by the scales of the Short-Form Health Survey. This held for the two summary scores. Notably, no significant interactions were found between age, gender, and nicotine dependence. The results of the regression analyses are presented in Table 3.

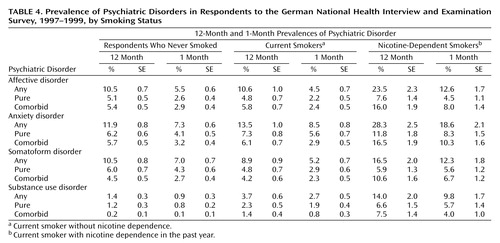

Statistically significant associations were found between nicotine dependence and psychiatric comorbidity (Table 4). More than half (52.4%) of the subjects with nicotine dependence fulfilled criteria for at least one other mental disorder, while one-fourth of the nondependent smokers and nonsmokers reported at least one mental disorder in the past year (27.2% and 25.6%, respectively). Affective and anxiety disorders were almost twice as common among dependent smokers as nonsmokers, and dependent smokers were more likely to suffer from another substance use/abuse disorder. Additionally, most of the dependent smokers with psychiatric comorbidity had two or more disorders in the last year and in the last month. The 12-month and 1-month prevalences for all diagnostic categories except substance abuse/dependence were similar for the nondependent smokers and nonsmokers.

Looking at the distribution of disability during the last month and the last year, we found significant differences with respect to smoking status. Approximately one-fourth of the dependent smokers had at least 14 days in the last year in which they could not carry out their normal activities in comparison to 15.1% of the nonsmokers. The same pattern of results was observed when we analyzed disability days in the last month. The subjects suffering from nicotine dependence reported greater disability in the last month. The results are presented in Table 5.

Discussion

In this article, we sought to quantify the association between nicotine dependence and health-related quality of life, disability, and associated psychiatric disorders. We found that among a sample of respondents to the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey of persons 18 to 65 years of age, the prevalence of DSM-IV nicotine dependence was 9.4%. More than a quarter of current smokers met diagnostic criteria for nicotine dependence. Nicotine-dependent smokers reported significantly poorer quality of life and greater disability than nonsmokers. Additionally, persons with nicotine-dependent disorder were about twice as likely to suffer from another mental disorder. In contrast, only small differences were noted when we compared quality of life and disability across nondependent smokers and nonsmokers.

The estimate of the lifetime prevalence of nicotine dependence in the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey was lower than the estimate in the National Comorbidity Survey, as reported by Breslau et al. (12) (15.6% and 24.1%, respectively), while the lifetime prevalence of smoking was somewhat higher in the German sample. These different results may be partly explained by sample characteristics (National Comorbidity Survey age range=15–54, or German National Health Interview and Examination Survey age range=18–64), different approaches in the assessment of smoking (interview versus questionnaire), and diagnostic classification (National Comorbidity Survey, DSM-III-R, German National Health Interview and Examination Survey, or DSM-IV). However, there is some evidence that the differences between DSM-III-R and DSM-IV have little influence on the prevalence estimates of nicotine dependence (22).

Mean scores on the Short-Form Health Survey for the nicotine-dependent group were lower than those of the other groups for seven of eight dimensions, indicating that nicotine dependence was associated with significantly poorer health perception. Current smokers had slightly higher scores on the Short-Form Health Survey scales than nonsmokers. When comparing these groups, one should keep in mind that there was a higher prevalence of chronic disease among the nonsmokers and that chronic diseases per se were associated with poorer health-related quality of life.

In a recent article, Sprangers and colleagues (23) analyzed data regarding health-related quality of life from several studies regarding a wide range of chronic disorders. Compared to these results, dependent smokers in our study reported poorer mental functioning than subjects suffering from chronic diseases.

The available literature on smoking and health primarily addresses smoking as a risk factor for subsequent health problems. Cross-sectional studies on smoking and quality of life suggest that smokers have poorer quality of life than nonsmokers (24), although findings are not consistent across studies. Several studies found that smokers are more likely to report symptoms of depression or anxiety than nonsmokers (25). Other studies found that smokers were more depressed; observed differences in levels of symptoms between smokers and nonsmokers were explained by sociodemographic differences (26). However, it is possible that the proportion of dependent smokers plays an important role in evaluations of health status in smokers (27) since nicotine dependence in our study was associated with poorer quality of life.

Previous research has demonstrated that cigarette smoking is associated with psychiatric disorders (9, 28, 29). In the present study, we found significantly higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity in dependent smokers than in nondependent smokers.

In evaluating these results, it is important to keep in mind that the interviewers conducted a full interview for DSM-IV disorders. Thus, in their assessment of nicotine dependence, they were not blind to other psychiatric morbidities. The interviewers may have been more likely to diagnose nicotine dependence when other morbidities coexisted.

In additional analyses, we used self-reports of the number of cigarettes smoked daily as an alternative criterion for nicotine dependence. First, the number of cigarettes was dichotomized such that subjects with a smoking habit of more than 20 cigarettes per day were classified as nicotine-dependent smokers, while subjects who smoked fewer than 20 cigarettes per day were classified as current smokers. Second, we entered the number of cigarettes as a continuous variable in the linear regression model. However, a similar pattern of results was obtained. With the dichotomized self-report criterion, we found that the dependent smokers reported significantly poorer quality of life and greater disability than the nonsmokers. These results remained stable when we controlled for sociodemographic characteristics and chronic diseases in the linear regression models. Additionally, there were no significant differences between current smokers and nonsmokers with respect to health-related quality of life. The number of cigarettes was significantly associated with poorer health-related quality of life in the regression models. These results might support efforts to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked.

Given the high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity, identification of individuals with nicotine dependence may be an important issue in developing prevention programs. Previous investigations have established that smokers with a history of mental disorders have a low rate of success rate in stopping smoking. Therefore, professionals delivering smoking-cessation programs should ask their potential patients about a personal and family history of mental disorders, and they should focus on both nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders. Effective tobacco-dependence treatment strategies exist at several distinct levels of intervention. Two publications provide a blueprint effectively intervening with tobacco use (30, 31). For European countries, there is an initiative of the World Health Organization European Partnership Project to reduce tobacco dependence. Their recommendations include strategies at the level of the clinician, at the level of the health care system, and at the societal level (32).

Since dependent smokers reported greater functional impairment than nondependent smokers, it is possible that nicotine dependence confers greater risk of short-term and long-term adverse health outcomes than smoking alone. Further research in this area is needed to clearly characterize the risks of mortality and morbidity for nicotine-dependent smokers.

An unresolved problem in the established association between nicotine dependence and psychiatric comorbidity is the issue of causality. There may be separate specific causal mechanisms from smoking to mental disorders and vice versa. For example, it has been often suggested that some smokers start to maintain smoking to self-medicate psychiatric symptoms (mainly depressive symptoms) since the psychoactive effects of nicotine help elevate their mood (33). On the other hand, there is some evidence that cigarette smoking contributes to the development of mental disorders (mainly anxiety disorders [29]) because of various factors, including impaired respiration and the presumed anxiogenic effects of nicotine (34). However, a likely situation is that people who have difficulty coping with stress, anxiety, and depression are more vulnerable to dependency (somehow the drug allows them to escape emotionally); that dependency may cause a vicious cycle—not being able to quit is stressful, which can increase anxiety. Nevertheless, it is also possible that smoking may be a marker of a variety of genetic, personal, social, and familial properties.

Smoking is well known to be a risk factor associated with high and preventable mortality and morbidity. However, our results and the study by Breslau et al. (12) suggest that it is important to distinguish nicotine dependence from smoking when evaluating the health status of populations. Focusing on smoking alone may result in misleading conclusions when evaluating the success of tobacco control since the impairment associated with nicotine dependence is ignored.

The gold standard for diagnosis of nicotine dependence comes from DSM-IV and ICD-10. However, short screening questionnaires may provide a means for early identification of nicotine dependence (35). These questionnaires may provide important information in both clinical practice and epidemiological research.

Nicotine dependence per se has been studied much less than alcohol or other drug dependencies. Serial cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of nicotine dependence are needed to determine whether the prevalence of nicotine dependence among smokers is increasing over time and whether certain groups are especially vulnerable to developing nicotine dependence if they start smoking. Further information is needed about the natural history of nicotine dependence (e.g., how soon it develops, whether some smokers are immune to developing dependence).

In the present study, we did not distinguish between cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking. However, cigar and pipe smokers represent an interesting subgroup since they have a different sociodemographic profile (more often male, with a higher socioeconomic status, and more often married) and they did not fulfill the diagnostic criteria for nicotine dependence, with three exceptions.

The present findings are constrained by several limitations. First, the data were cross-sectional, and although the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey is population-based, we were unable to longitudinally determine the relationship between nicotine dependence and quality of life, disability and psychiatric comorbidity. Second, the subjects ages 66 and older were excluded from the second stage of the survey because of the psychometric shortcomings of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview in older populations. Therefore, we could draw no conclusions regarding associations in older populations. Nevertheless, there is some evidence that the absence of cigarette abuse before age 50 is an important protective factor for successful aging, as pointed out in a recent longitudinal study (36).

Third, smoking status was assessed by self-report. Therefore, it is possible that misclassification of cigarette smoking status may have occurred (37). Fourth, because the measures of functional limitation and disability were based on self-reports, the question of differences in reporting rather than actual limitations may have been raised. It would have been interesting to compare our results with data from health care providers and medical records. Unfortunately, these data were not available.

|

|

|

|

|

Received July 16, 2002; revision received Jan. 10, 2003; accepted Jan. 13, 2003. From the Clinic for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, Heinrich-Heine-University; and the Department of Public Health, Medical School Dresden, Dresden, Germany. Address reprint requests to Dr. Schmitz, Clinic for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, Heinrich-Heine-University, Bergische Landstr. 2, H19, D-40605 Duesseldorf, Germany; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank Hans-Ulrich Wittchen, Ph.D., Heribert Stolzenberg, Ph.D., and Bärbel-Maria Kurth, Ph.D., for help with the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey public use databases.

1. World Health Organization: Tobacco or Health: A Global Status Report. Geneva, WHO, 1997Google Scholar

2. Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M, Heath C Jr, Doll R: Mortality from smoking worldwide. Br Med Bull 1996; 52:12–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Glassman AH: Cigarette smoking: implications for psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:546–553Link, Google Scholar

4. Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottier LB, Steiner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J: Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA 1990; 264:1546–1549Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Mitchell JE, Dahlgren LA: Prevalence of smoking among psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:993–997Link, Google Scholar

6. de Leon J, Dadvand M, Canuso C, White AO, Stanilla JK, Simpson GM: Schizophrenia and smoking: an epidemiological survey in a state hospital. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:453–455Link, Google Scholar

7. Breslau N, Klein DF: Smoking and panic attacks: an epidemiologic investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:1141–1147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kendler KS, Neale MC, Sullivan P, Corey LA, Gardner CO, Prescott CA: A population-based twin study in women of smoking initiation and nicotine dependence. Psychol Med 1999; 29:299–308Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH: Smoking and mental illness—a population-based prevalence study. JAMA 2000; 284:2606–2610Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. US Department of Health and Human Services: Health Consequences of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1994Google Scholar

11. Hughes JR: Distinguishing nicotine dependence from smoking—why it matters to tobacco control and psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:817–818Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hiripi E, Kessler R: Nicotine dependence in the United States: prevalence, trends, and smoking persistence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:810–816Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bellach BM, Knopf H, Thefeld W: [The German Health Survey 1997/98.] Gesundheitswesen 1998; 60(suppl 2):S59-S68 (German)Google Scholar

14. Wittchen H-U, Mueller N, Storz S: Psychische Störungen: Häeufigkeit, psychosoziale Beeinträchtigungen und Zusammenhäenge mit köerperlichen Erkrankungen. Gesundheitswesen 1998; 60(suppl 2):S95-S100Google Scholar

15. Wittchen HU, Carter RM, Pfister H, Montgomery SA, Kessler RC: Disabilities and quality of life in pure and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in a national survey. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 15:319–328Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1. Geneva, Switzerland, WHO, 1997Google Scholar

17. Knauper B, Wittchen HU: Diagnosing major depression in the elderly—evidence for response bias in standardized diagnostic interviews. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:147–164Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30:473–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Public Use File PS, Bundesgesundheits-survey “Psychische Stöerungen.” Munich, Max-Planck-Institut für Psychiatrie, 2000Google Scholar

20. Public Use File BGS98, Bundes-Gesundheitssurvey. Berlin, Robert-Koch-Institut, 2000Google Scholar

21. Stata Reference Manual: Release 7.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2000Google Scholar

22. Breslau N, Johnson EO: Predicting smoking cessation and major depression in nicotine-dependent smokers. Am J Public Health 2000; 90:1122–1127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Sprangers MAG, de Regt EB, Andries F, van Agt HM, Bijl RV, de Boer JB, Foets M, Hoeymans N, Jacobs AE, Kempen GI, Miedema HS, Tijhuis MA, de Haes HC: Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol 2000; 53:895–907Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Wilson D, Parsons J, Wakefield M: The health-related quality-of-life of never smokers, ex-smokers, and light, moderate, and heavy smokers. Prev Med 1999; 29:139–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Anda RF, Williamson DF, Escobedo LG, Mast EE, Giovino GA, Remington PL: Depression and the dynamics of smoking: a national perspective. JAMA 1990; 264:1541–1545Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Son BK, Markovitz JH, Winders S, Smith D: Smoking, nicotine dependence, and depressive symptoms in the CARDIA Study: effects of educational status. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 145:110–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P: Vulnerability to psychopathology in nicotine-dependent smokers: an epidemiologic study of young adults. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:941–946Link, Google Scholar

28. Jorm AF: Association between smoking and mental disorders: results from an Australian National Prevalence Survey. Aust NZ J Public Health 1999; 23:245–248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS: Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA 2000; 284:2348–2351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000Google Scholar

31. Task Force on Community Preventive Services: Introducing the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med 2000; 18(suppl):1–142Google Scholar

32. Raw M, Anderson P, Batra A, Dubois G, Harrington P, Hirsch A, Le Houezec J, McNeill A, Milner D, Poetschke Langer MP, Zatonski W (World Health Organization European Partnership Project to Reduce Tobacco Dependence): WHO Europe evidence based recommendations on the treatment of tobacco dependence. Tob Control 2002; 11:44–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Glass RM: Blue mood, blackened lungs: depression and smoking. JAMA 1990; 264:1583–1584Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. West R, Hajek P: What happens to anxiety levels on giving up smoking? Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1589–1592Link, Google Scholar

35. Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, Flessland KA, Pomerleau OF: Reliability of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire and the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. Addict Behav 1994; 19:33–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Vaillant GE, Mukamal K: Successful aging. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:839–847Link, Google Scholar

37. Wagenknecht LE, Burke GL, Perkins LL, Haley NJ, Friedman GD: Misclassification of smoking status in the CARDIA Study: a comparison of self-report with serum cotinine levels. Am J Public Health 1992; 82:33–36Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar