Sexual Orientation and Self-Harm in Men and Women

Abstract

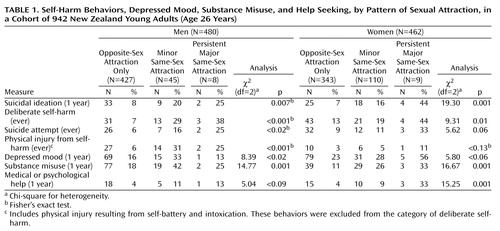

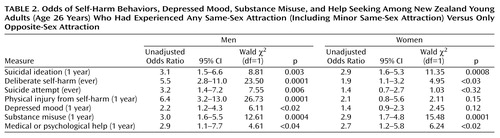

OBJECTIVE: Recent studies of homosexual people have found higher rates of nonfatal suicidal behavior than among heterosexuals. The purpose of this study was to determine associations between self-harm and sexual orientation for men and women separately, defining sexual orientation by sexual attraction rather than by behavior. METHOD: In a birth cohort of 1,019 New Zealand young adults eligible to be interviewed at age 26 years, 946 participated in assessments of both sexual attraction and self-harm. RESULTS: Both women and men who had experienced same-sex attraction had higher risks of self-harm. The odds ratios for suicidal ideation in the past year were 3.1 for men and 2.9 for women. Odds ratios for ever having deliberately self-harmed were 5.5 for men and 1.9 for women. Men with same-sex attraction were also significantly more likely to report having attempted suicide. In both sexes, a greater degree of same-sex attraction predicted increasing likelihood of self-harm, with over one-third of men and women with persistent major same-sex attraction reporting this. Men with even a minor degree of same-sex attraction had high rates of self-harm and resulting physical injury. One-quarter of deliberate self-harm among men and one-sixth among women was potentially attributable to same-sex attraction. CONCLUSIONS: This study provides evidence of a link between increasing degrees of same-sex attraction and self-harm in both men and women, with the possibility of some difference between the sexes that needs to be explored further.

Recent studies of homosexual people using population-based samples (1–8) have consistently shown higher rates of nonfatal suicidal behavior than among heterosexuals, but many questions about the relationship between sexual orientation and suicidal behavior have yet to be answered.

A key question is whether gender makes a difference. Since the factors that underlie male and female homosexuality may differ (9), the correlates may differ as well. Bailey (9) proposed that prenatal developmental influences and sex atypicality in some homosexual people might result in lesbians having opposite vulnerabilities to those of gay men.

Most population-based studies so far have either involved male subjects only (4, 5, 7, 8) or been forced to combine male and female subjects because of small group numbers (3, 6). Two school-based studies were analyzed for boys and girls separately. One found a higher risk of attempted suicide in boys but not in girls (2). The other found a higher risk for boys, but no significantly higher risk for girls after drug use and violence/victimization behaviors were adjusted for in a logistic regression model (1). However, such adjustment may have concealed an association, since both of these behaviors could be part of a causal pathway. Sexual orientation may emerge later in female than in male subjects (10), so studies restricted to adolescents may miss an association for adult women.

Earlier studies of selected groups of homosexual women (11, 12) found that they were more likely to have attempted suicide than heterosexual women. A comparison of homosexual men and women found that the women had mostly attempted suicide in their 20s, whereas most of the men had done so in their teens (13). If this age difference were generally the case, it would be another reason for examining attempted suicide in adulthood in order to determine any sex differences.

A problem affecting many studies is the definition of homosexuality. Often the definition has been based on same-sex behavior rather than orientation, and the two are not synonymous. Three overlapping dimensions of homosexuality can be identified: same-gender sexual behavior, desire, and identity (14). Bailey (9) considered that patterns of sexual attraction and fantasy are preferable to sexual behavior for defining homosexuality. He described a particular problem of potential confounding: experimentation with same-sex behavior among heterosexually oriented people could be associated with personality traits such as impulsivity, which could in turn relate to suicidal behavior.

A challenge for research in the area of suicide and deliberate self-harm is to be clear about definitions (15, 16). Terms such as “attempted suicide” or “suicidal behavior” may refer to episodes involving suicidal intent but are often used for reports of self-harm in which people survive without specifying intention. The term “deliberate self-harm,” which avoids ascribing intent, has much to commend it (17).

We had an opportunity to study the associations between patterns of sexual attraction and self-harm in a birth cohort of New Zealanders aged 26 years. We were able to distinguish between deliberate self-harm (which may or may not be suicidal in intent) and attempted suicide, in which the intention to die was specified. Our aim was to examine associations between sexual orientation and these behaviors separately in young men and women.

Method

Sample

The sample was from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a longitudinal study of a cohort of 1,037 individuals born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in 1972–1973 and still living in the province of Otago at the age of 3 (18). The study participants were seen at age 3 years then at repeated intervals for extensive medical, psychological, and behavioral assessment. There were 1,019 participants alive and eligible to be interviewed at age 26. This report is based on 946 study members (92.8% of the surviving cohort) who participated in assessments of both their sexual orientation and self-harm behaviors at age 26. After complete description of the study to the participants, they gave written informed consent for both assessments.

Sexual Orientation

Two questions about sexual orientation were presented as part of a computer-based assessment of sexual behavior. These dealt with past and current sexual attraction (“What best describes who you have ever felt sexually attracted to?” and “What best describes who you these days feel sexually attracted to?”) and were based on the 1990 British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (19). The participants had to choose one of six options. Men, for example, chose from the following: “only to males, never to females; more often to males and at least once to a female; about equally often to males and females; more often to females and at least once to a male; only ever to females, never to males; never attracted to anyone at all.” Four women were excluded from the analysis because they reported no sexual attraction to either sex. The remaining 942 were divided into three groups in a way that reflected their behavior both “these days” and “ever” in order to relate these attraction patterns to lifetime deliberate self-harm.

The group with only opposite-sex attraction comprised 427 men and 343 women who reported being attracted only to the opposite sex both “these days” and “ever.” The group with persistent major same-sex attraction comprised eight men and nine women who were attracted equally more or only to the same sex both “these days” and “ever.” The rest formed the third group of 45 men and 110 women who comprised the group with minor same-sex attraction. They had recorded mainly opposite-sex attraction either “these days,” “ever,” or both but also some same-sex attraction (at least once). Over one-third of this group reported some same-sex attraction “ever” but only opposite-sex attraction “these days,” while three had moved from only opposite-sex attraction “ever” to same-sex attraction “these days.” One man reported major same-sex attraction “ever” but only opposite-sex attraction “these days,” while one woman reported the reverse.

Self-Harm

The participants were asked in detail about deliberate self-harming behaviors, with or without suicidal intent, in a 20-minute semistructured interview conducted by trained female interviewers. The term “deliberate self-harm” was used to describe all episodes involving methods coded as E950–E957 in ICD-9 for suicide and self-inflicted injury, with the addition of purposely crashing a car. The definition of deliberate self-harm thus included episodes in which death had clearly been intended as well as episodes in which suicidal intent was ambiguous or absent (17). A small number of key variables were selected for this report: suicidal ideation (elicited only for the past year), lifetime deliberate self-harm, regardless of intent, lifetime suicide attempts (a subset of deliberate self-harm for which the participant specified that the intention was suicide), self-harm that resulted in physical injury (including physical injuries resulting from self-harmful behavior falling below the deliberate self-harm threshold—self-battery and intoxication with alcohol or other substances as a way of dealing with emotional pain), and any medical or psychological attention received for self-harm. These last two variables were ascertained for the past year only.

Depressed Mood and Substance Misuse

Since mental health may mediate between sexual orientation and self-harm, two simple questions relating to depressed mood and substance misuse (for the past year only) were included. In response to the question regarding depressed mood, 85 men and 115 women reported a period of 2 weeks or more in which nearly every day they had felt sad or depressed, had felt moody or irritable, or had lost all interest in things.

The other question inquired about use of alcohol (or other substances) in the past year to become intoxicated as a way of dealing with psychological pain. Two or more episodes of such substance use in the past year were taken to be a simple indicator of substance misuse: such use was reported by 98 men and 71 women.

Demographic Variables

The following demographic variables in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study at age 26 years were compared in the three sexual-orientation groups (men and women separately): ethnic group (Maori versus other), educational attainment, employment, socioeconomic status, whether living with a spouse or partner, whether parent of one or more biological children, and residence in New Zealand for 6 or more months during the previous year.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare differences between sexual-orientation groups for self-harm variables, and Mantel-Haenszel tests for trend were reported when an association could be described as a trend.

After we combined the two groups with any same-sex attraction into one group, logistic regression was used to obtain odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between the two sexual-orientation groups and self-harm variables, using the group reporting only opposite-sex attraction as the reference group. Another model considered potential demographic confounders and yet another, the effect of adjusting for depressed mood and substance misuse. Logistic regression was also used to examine the interaction between gender and sexual orientation. The interaction was regarded as significant if the change in deviance was greater than the critical value of the chi-square distribution with appropriate degrees of freedom. A large number of statistical tests were carried out, so the results should be interpreted cautiously.

Population-attributable risks for any same-sex attraction, assuming a causal relationship with deliberate self-harm and attempted suicide, were calculated for men and women separately (20).

Results

Self-harm behaviors varied according to sexual orientation, as shown in Table 1. The differences among the groups were statistically significant (p<0.01) for all four measures of self-harm behavior (including suicidal ideation) among men, although it should be noted that the self-harm behaviors of some people fell into more than one category. Among women, the differences were significant for suicidal ideation in the past year and ever having deliberately self-harmed. Self-harm was more likely if the participant had experienced persistent major same-sex attraction. Men with even a minor degree of same-sex attraction had high rates of self-harm.

There was a significant increase in the risk of self-harming behavior with increasing degree of same-sex attraction in both sexes for suicidal ideation (trend for men: χ2=9.81, df=1, p=0.007; trend for women: χ2=16.64, df=1, p=0.001) and ever having deliberately self-harmed (trend for men: χ2=27.69, df=1, p=0.001; trend for women: χ2=7.42, df=1, p=0.006). Among men, there was also a significant gradient for ever having attempted suicide (χ2=9.15, df=1, p=0.002). For physical injuries among men, there was a significant increase, with those with minor same-sex attraction reporting the highest risk (χ2=32.80, df=1, p=0.001).

The likelihood of having experienced an episode of depressed mood in the past year increased significantly for men according to pattern of sexual attraction; men with minor same-sex attraction reported the highest risk (χ2=7.58, df=1, p=0.006). A similar pattern was seen for substance misuse in the past year among men (χ2=14.61, df=1, p=0.001). For women, a significant increase for increasing substance misuse with increasing degree of same-sex attraction was found (χ2=16.31, df=1, p=0.001).

Unadjusted odds ratios for self-harm according to sexual attraction are shown in Table 2. For this analysis, all who had experienced any same-sex attraction (including those with only minor same-sex attraction) were combined into one group. Odds ratios for this group were calculated relative to those who had experienced only opposite-sex attraction (the reference group). This was necessary because there were too few people with persistent major same-sex attraction to allow separate analysis. For men with any same-sex attraction, odds ratios were high on all measures of self-harm behavior. For women in the same group, odds ratios were significantly higher for suicidal ideation and for having deliberately self-harmed.

Comparison of demographic characteristics of the three sexual-orientation groups resulted in the finding of only two appreciable differences. Men and women with persistent major same-sex attraction were less likely to be living with a spouse or partner. Men who had experienced any same-sex attraction were more likely to be in the higher of two categories for educational attainment. In case this educational advantage had caused confounding with regard to risk of self-harm, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to adjust for educational achievement. This resulted in higher odds ratios for all the variables shown in Table 2. For example, the odds ratio for suicidal ideation rose from 3.1 to 3.5 (95% CI=1.6–7.7) and that for deliberate self-harm rose from 5.5 to 8.4 (95% CI=3.9–18.3). Logistic regression analysis was also used to adjust for Maori ethnicity (women only) and unemployment at age 26 years in case these variables led to confounding, but there was little change in the odds ratios for the variables in Table 2 when this was done.

When possible gender differences were tested, men in the group with any same-sex attraction were found to be at a significantly higher risk than women in the same group for reporting lifetime deliberate self-harm (change in deviance=5.905, df=1, p<0.02).

As shown in Table 2, both men and women with any same-sex attraction (compared with the reference group) were much more likely to receive help and to misuse substances in the past year. The higher odds of having had a depressed mood in the past year was significant for men only.

When logistic regression analysis was used to account for the effect of past-year depressed mood on past-year self-harm among those with any same-sex attraction, odds ratios that had been significantly higher remained so, although they were reduced in magnitude. Among men, the unadjusted odds ratios for suicidal ideation and physical injury from self-harm were 3.1 and 6.4, respectively. The odds ratios after adjustment for depressed mood were 2.4 [CI=1.1–5.6] and 5.6 [CI=2.7–11.8], respectively. Among women, the unadjusted odds ratios for suicidal ideation and physical injury from self-harm were 2.9 and 2.1, respectively. The odds ratios after adjustment for depressed mood were 2.7 [CI=1.4–5.2] and 2.0 [CI=0.7–5.3], respectively. The relatively wide confidence intervals indicate that the estimates are not especially precise. It did not, therefore, seem appropriate to adjust for other variables.

Calculation of attributable risks indicated that for the outcome of lifetime deliberate self-harm, if the risk factor (any same-sex attraction) were absent, the proportion of men in the population reporting deliberate self-harm would be reduced by 26% and the proportion of women reporting deliberate self-harm would be reduced by 15%. The expected reductions in the proportions of the male and female populations that would report having attempted suicide if the risk factor were absent were somewhat lower: 16% for men and 8% for women.

Comment

In this birth cohort of young adults in New Zealand, women as well as men who had experienced same-sex attraction had a higher risk of self-harm behaviors. Both sexes had high odds for suicidal ideation and deliberate self-harm. Moreover, in both sexes, a greater degree of same-sex attraction predicted an increasing likelihood of some self-harm behaviors. As much as one-quarter of deliberate self-harm among men and one-sixth among women was potentially attributable to the risk factor of same-sex attraction. Our definition of deliberate self-harm was based on the ICD-9 codes for suicide and self-inflicted injury.

These findings confirm the link between sexual orientation and suicidal behavior in men and provide evidence that this also applies to women. The two previous studies that examined female subjects separately involved adolescents (1, 2); several factors might explain why only one study found any higher risk. Since sexual orientation may emerge later in female subjects (10), some teenage girls might not have experienced same-sex attraction by the ages at which the school-based surveys were conducted or not have been willing at that stage to label their attraction as homosexual or bisexual orientation. In contrast, the adult women in our study had more years of life experience, which would have given them a greater opportunity to develop consciousness of their sexuality. Also, they were not asked to specify orientation, only pattern of sexual attraction. The small group numbers in the present study did not enable comparison of the age of onset of deliberate self-harm in men and women with same-sex attraction, but if deliberate self-harm occurred later in women (13), this could also explain why studies of adolescent girls have found little increased risk.

The associations found between sexual orientation and self-harm were not identical in men and women. Men with any same-sex attraction were at a greater risk of deliberate self-harm relative to other men than were women with same-sex attraction. While this difference could have been due to chance, it could also be explained by any differences between the sexes in readiness to admit to same-sex attraction. The cohort as a whole is more accepting of same-sex relationships between women than between men (21). If it is less socially acceptable for men to admit to same-sex attraction, perhaps only men with a considerable degree of same-sex attraction were willing to admit it at all. This would explain the smaller numbers of men with minor same-sex attraction. Women, on the other hand, might have been more open about minor degrees of same-sex attraction, resulting in a larger group. Given that the risk of deliberate self-harm was higher with increasing degrees of same-sex attraction, any difference between men and women in the likelihood of reporting minor same-sex attraction could have affected the overall risk when those with any same-sex attraction were combined into one group.

Another possibility is that there is a real difference in the self-harm behavior of men and women with same-sex attraction. Perhaps same-sex attraction is more troubling to men than it is to women. Even minor same-sex attraction in men was associated with higher rates of self-harm and resulting physical injury. More men than women in the cohort as a whole thought that sex between two members of their own gender was “always wrong” (21). This might lead to more difficulties for men who experience same-sex attraction.

In calculating attributable risk for any same-sex attraction, an assumption was made that there was a causal relationship between same-sex attraction and self-harm, although the temporal relationship was not established, and in some cases, the self-harm may have preceded the same-sex attraction. The causal pathways that lead to deliberate self-harm and attempted suicide are likely to be complex, so same-sex attraction could—to some degree—be a marker for a range of factors that contribute to these behaviors. To our knowledge, previous work on sexual orientation and suicidal behavior has not included determination of attributable risks. From data on suicide attempts in the report by Fergusson and colleagues (6), we calculated an attributable risk of 9% for gay, lesbian, or bisexual orientation (this definition included some with same-sex behavior only) for both sexes combined. This provides corroboration that a meaningful reduction of suicidal behavior in the community could occur if the aspects of same-sex attraction that are associated with suicidal behavior could be ameliorated. For example, the role of societal attitudes needs to be further explored. The high risks we report occurred despite the fact that young adults in New Zealand are far more accepting of same-sex relationships than are their American counterparts (21).

This study had a number of limitations. Although we were able to avoid the problem of determining sexual orientation indirectly through sexual behavior, it is not known how the participants would have identified their own sexual orientation. Small group numbers forced us to combine all those with any same-sex attraction into one group in order to calculate odds ratios for the two sexes separately. If the threshold for women acknowledging minor same-sex attraction were lower, this might have reduced the likelihood of finding significantly higher odds ratios for women with same-sex attraction. The small number with persistent major same-sex attraction also prevented us from taking into account potential mediating risk factors. We attempted this for depressed mood (elicited for the past year only and a weaker measure than diagnosed disorder), but the results indicated that pursuing further possible mediating factors would be too unreliable an exercise with this group size. The group with any same-sex attraction included those whose experience of same-sex attraction had been only in the past, so when depressed mood was reported, this could have occurred during a period of opposite-sex attraction.

Another limitation of research of this kind is that same-sex attraction and self-harm will not always be disclosed, since they could be regarded as stigmatizing. Same-sex attraction may have been reported more consistently in this study than in some earlier ones because of the age of the participants, the presentation of questions by computer, and the fact that the participants were not asked to specify their sexual orientation. Moreover, members of this cohort had been assessed repeatedly throughout their lives with no breaches of confidentiality, perhaps resulting in more openness. Nevertheless, it is likely that neither same-sex attraction nor self-harm was fully disclosed, so the link between same-sex attraction and self-harm could have been underestimated.

There is also, however, a contrary possibility: a willingness to disclose socially stigmatizing information about one’s sexuality might be associated with a similar willingness to disclose suicidal behavior, depressive symptoms, or substance misuse (8).

Help seeking among homosexual people who have engaged in suicidal behavior has received little attention. Although small group numbers made comparisons difficult, some help was received for deliberate self-harm across all three sexual-attraction groups. This suggests that sexual-orientation issues had not barred help seeking for at least some of those in need.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence of a link between increasing degrees of same-sex attraction and self-harm in both men and women, with the possibility of some difference between the sexes that needs to be explored further. Not only are the risks of self-harm among those with same-sex attraction important at a clinical level, but from a population perspective, a material reduction in occurrence of deliberate self-harm might be expected if the links between same-sex attraction and self-harm could be broken.

|

|

Received May 8, 2001; revisions received Nov. 27, 2001, and June 18, 2002; accepted July 25, 2002. From the Department of Psychological Medicine and the Injury Prevention Research Unit, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago Medical School. Address reprint requests to Dr. Skegg, Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Otago School of Medicine, P.O. Box 913, Dunedin, New Zealand; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (grants 98/148 and 98/152) and a research fellowship from the Community Trust of Otago (to Dr. Nada-Raja); grant 98/148 was made to the Injury Prevention Research Unit, which is supported by the Health Research Council and the Accident Compensation Corporation. The authors thank Dr. Richie Poulton (Director of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study), Prof. John Langley, Ms. Nicola Brown, and Prof. Sarah Romans for critical comment and the members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study.

1. Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Wissow LS, Woods ER, Goodman E: Sexual orientation and risk of suicide attempts among a representative sample of youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999; 153:487-493Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Remafedi G, French S, Story M, Resnick MD, Blum R: The relationship between suicide risk and sexual orientation. Am J Public Health 1998; 88:57-60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Faulkner AH, Cranston K: Correlates of same-sex sexual behavior in a random sample of Massachusetts high school students. Am J Public Health 1998; 88:262-266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Bagley C, Tremblay P: Suicidal behaviors in homosexual and bisexual males. Crisis 1997; 18:24-34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. DuRant RH, Krowchuk DP, Sinal SH: Victimisation, use of violence, and drug use at school among male adolescents who engage in same-sex sexual behavior. J Pediatr 1998; 132:13-18Google Scholar

6. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL: Is sexual orientation related to mental health problems and suicidality in young people? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:876-880Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Herrell R, Goldberg J, True WR, Ramakrishnan V, Lyons M, Eisen S, Tsuang MT: Sexual orientation and suicidality. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:867-874Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Cochran SD, Mays VM: Lifetime prevalence of suicide symptoms and affective disorders among men reporting same-sex sexual partners: results from NHANES III. Am J Public Health 2000; 90:573-578Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bailey JM: Homosexuality and mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:883-884Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. D’Augelli AR: Lesbian, gay, and bisexual development during adolescence and young adulthood, in Textbook of Homosexuality and Mental Health. Edited by Cabaj RP, Stein TS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996, pp 267-288Google Scholar

11. Bell AP, Weinberg MS: Homosexualities. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1978Google Scholar

12. Saghir MT, Robins E, Walbran B, Gentry KA: Homosexuality, IV: psychiatric disorders and disability in the female homosexual. Am J Psychiatry 1970; 127:147-154Link, Google Scholar

13. Saghir MT, Robins E: Male and Female Homosexuality. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1973Google Scholar

14. Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S: The Social Organization of Sexuality. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994Google Scholar

15. Linehan MM: Suicidal people, in Psychobiology of Suicidal Behavior. Edited by Mann JJ, Stanley M. New York, New York Academy of Sciences, 1986, pp 16-33Google Scholar

16. O’Carroll PW, Berman AL, Maris RW, Moscicki EK, Tanney BL, Silverman MM: Beyond the Tower of Babel: a nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1996; 26:237-252Medline, Google Scholar

17. Morgan HG, Burns-Cox CJ, Pocock H, Pottle S: Deliberate self-harm: clinical and socio-economic aspects of 368 patients. Br J Psychiatry 1975; 127:564-574Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Silva PA, Stanton WR: From Child to Adult: The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

19. Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Field J: Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. Oxford, UK, Blackwell, 1994Google Scholar

20. Campbell MJ, Machin D: Medical Statistics: A Commonsense Approach. West Sussex, UK, John Wiley & Sons, 1990Google Scholar

21. Dickson N, Paul C, Herbison P: Same-sex attraction in a birth-cohort: prevalence and persistence in early adulthood. Soc Sci Med (in press)Google Scholar