The “Dreamy State”: John Hughlings-Jackson’s Ideas of Epilepsy and Consciousness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors review John Hughlings-Jackson’s writings on the “dreamy state” and his subsequent derivation of degrees of consciousness. METHOD: They reviewed the publications of Hughlings-Jackson from his initial description of the “dreamy state” in 1876 until his writing about the “uncinate group of fits” in 1899. They then examined Hughlings-Jackson’s use of the associated signs and symptoms of the “dreamy state” to formulate his ideas about human consciousness. RESULTS: Hughlings-Jackson defined the “dreamy state” as “over-consciousness,” or a heightened intellectual state. He described associated symptoms of “crude sensations” of smell and taste, an unusual epigastric sensation, chewing and lip smacking, automatisms, postictal symptoms, and at least some degree of alteration of consciousness. Using his observations of the “dreamy state” as a model, Hughlings-Jackson proposed three degrees of consciousness, each with an object and subject component. CONCLUSIONS: Through his description of the “dreamy state,” Hughlings-Jackson accurately characterized and localized medial temporal epilepsy. Correlating the ictal semiology of the “dreamy state” with consciousness, he developed a theory of consciousness that remains relevant to current understanding of the mind-brain relationship.

John Hughlings-Jackson revolutionized the theories of pathophysiology of epilepsy (1, 2). His detailed descriptions of focal motor seizures resulted in the eponym “Jacksonian epilepsy,” and he also wrote extensively on another type of epilepsy, which he called the “dreamy state.” Carefully collecting case histories throughout his career, he eventually associated the “dreamy state,” and its associated signs and symptoms, with the medial temporal region. Using his theories of organization of the nervous system, he also wrote about the implications of the “dreamy state” in human consciousness and thought, leading to concepts that continue to be relevant to ideas of consciousness today.

Many authors have independently outlined Hughlings-Jackson’s writings on the “dreamy state” (1, 3, 4) or his models of consciousness (5–9), but there are no thorough reviews of how he derived his models of consciousness primarily from his observations of the “dreamy state.” We reviewed all of Hughlings-Jackson’s published writings about the “dreamy state,” summarized these writings, and examined his derivation of degrees of consciousness based on the model of the “dreamy state.”

Pathophysiology of Epilepsy

In speaking of classification of the epilepsies, including the “dreamy state,” Hughlings-Jackson wrote,

We shall ultimately be able not only to speak of certain symptoms as constituting genuine epilepsy or some variety of it, but of these or those particular symptoms as pointing to a “discharging lesion” of this or that particular part of cortex. (10)

These ideas, far ahead of their time, reflect our concept of epilepsy today (2) and correlate with the current definition of focal (or partial) epileptic seizures as seizures “whose initial semiology indicates, or is consistent with, initial activation of only part of one cerebral hemisphere” (11).

The syndrome of medial temporal epilepsy is a localization-related epilepsy syndrome with associated ictal and postictal signs and symptoms resulting from activation of structures in the medial temporal region (12). Usually, Hughlings-Jackson’s use of the term “dreamy state” was synonymous with our current definition of the ictal and immediate postictal phenomenology of medial temporal epilepsy. However, he also used “dreamy state” to describe a specific symptom, which he believed to be a central feature of what is currently defined as the syndrome of medial temporal epilepsy. In this review we will use “dreamy state” synonymously with the ictal and immediate postictal semiology of medial temporal epilepsy. When referring to Hughlings-Jackson’s use of “dreamy state” as an isolated symptom, we will clarify with the term “symptom of the ‘dreamy state’ ” as necessary.

Description of the “Dreamy State”

Hughlings-Jackson’s first description of what he termed the “dreamy state” appeared in 1876 (10, 13). Throughout the rest of his career, he continued to publish articles about this variety of epilepsy. He wrote,

The so-called “intellectual aura” (I call it “dreamy state”) is a striking symptom. This is a very elaborate or “voluminous” mental state. One kind of it is a “Reminiscence”; a feeling many people have had when apparently in good health. (10)

This aura is now most often referred to as a feeling of familiarity, or déjà vu. However, Hughlings-Jackson’s broader definition of a heightened intellectual state, or “over-consciousness,” is perhaps a better description. With the symptom of the “dreamy state,” he further listed associated symptoms of “crude sensations” and at least some degree of alteration of consciousness (10).

Hughlings-Jackson also called the symptom of the “dreamy state” a “double consciousness.” In this state, patients were vaguely aware of ongoing events (one consciousness), but were preoccupied with the intrusion of an “all knowing” or “familiar” feeling (a second consciousness) (14, 15). He stated, “This double mental state helps the diagnosis of slight seizures greatly” (15).

Clinical Examples of the “Dreamy State”

Hughlings-Jackson included in his writings many clinical examples of the symptom of the “dreamy state” that are indispensable in understanding the symptom. Hughlings-Jackson based the name of the symptom, the “dreamy state,” on a “highly educated” patient’s description of symptoms:

The past is as if present, a blending of past ideas with present…a peculiar train of ideas of the reminiscence of a former life, or rather, perhaps, of a former psychologic state. (15)

The case of Dr. Z played a central role in Hughlings-Jackson’s descriptions and understanding of the “dreamy state.” Dr. Z was a “highly educated medical man” who had the “dreamy state.” In 1870, Dr. Z, writing under the pseudonym Quaerens (the seeker), published a brief article (16) quoting Coleridge, Tennyson, and Dickens to describe his symptoms. Dr. Z wrote detailed descriptions of his own seizures, reported by Hughlings-Jackson in 1888 (17, 18). Eventually, it was determined that Dr. Z was actually Dr. Alfred Thomas Meyers, a physician at the Belgrave Hospital in London, with whom Hughlings-Jackson was acquainted (3, 4). Meyers died in 1894 from an overdose of chloral (a class of sedative medication, used in modern-day medicine as chloral hydrate). Hughlings-Jackson participated in Meyers’ autopsy, finding a “very small patch of softening in the left uncinate gyrus” (18).

Dr. Z’s description of his first seizure was,

I was carelessly looking round me, watching people passing, &c., when my attention was suddenly absorbed in my own mental state, of which I know no more than that it seemed to me to be a vivid and unexpected “recollection”;—of what I do not know. (18)

Dr. Z described his own clinical events, shedding light on the nature of the symptoms of “double consciousness,” as follows:

I was attending a young patient whom his mother had brought me with some history of lung symptoms. I wished to examine the chest, and asked him to undress on a couch. I thought he looked ill, but have no recollection of any intention to recommend him to take to his bed at once, or of any diagnosis. Whilst he was undressing I felt the onset of a petit mal. I remember taking out my stethoscope and turning away a little to avoid conversation. The next thing I recollect is that I was sitting at a writing-table in the same room, speaking to another person, and as my consciousness became more complete, recollected my patient, but saw he was not in the room. I was interested to ascertain what had happened, and had an opportunity an hour later of seeing him in bed, with the note of a diagnosis I had made of “pneumonia of the left base.” (18)

Intrigued about the accuracy of his diagnosis, rendered during the “dreamy state,” Dr. Z proceeded as described below.

I gathered indirectly from conversation that I had made a physical examination, written these words, and advised him to take to bed at once. I re-examined him with some curiosity, and found that my conscious diagnosis was the same as my unconscious, —or perhaps I should say, unremembered diagnosis had been. I was a good deal surprised, but not so unpleasantly as I should have thought probable. (18)

Hughlings-Jackson also commented on patients’ attitudes toward their seizures. In a minority of cases, patients found the “dreamy state” pleasurable and would attempt to bring on the symptom (10, 19). He also noted a consistency of symptoms, quoting Falret: “These ideas, these remembrances, these false sensations, which differ singularly in different patients, are generally reproduced with remarkable uniformity in the same patient at each new attack” (20).

The “Crude Sensations”

In addition to the symptom of the “dreamy state,” Hughlings-Jackson observed other symptoms, which he referred to as “crude sensations” (10, 15). He considered them to be in the spectrum of the symptom of the “dreamy state” but much less elaborate. They included the following (10, 15): 1) “paroxysms beginning by an epigastric sensation,” 2) “fear (rarely anger),” 3) “paroxysms beginning by noises in the ear,” 4) “fits beginning by colored vision,” 5) “taste,” and 6) “a crude sensation of smell.”

Hughlings-Jackson wrote that the “crude sensations” could occur before, during, or after the symptom of the “dreamy state.” During a particular seizure, “crude sensations” and the symptom of the “dreamy state” could occur together or as isolated symptoms. Hughlings-Jackson postulated a relationship between the type of “crude sensations” and the symptom of the “dreamy state” but was unable to establish this from his case histories (10, 15).

Signs Associated With the “Dreamy State”

Hughlings-Jackson described ictal symptoms of pallor, sweating, tachycardia, lip smacking, and chewing movements. He considered lip smacking and chewing movements to be related to other gastrointestinal symptoms (such as the common aura of an epigastric sensation):

I think it will be found that in many, I dare not say in most, cases the voluminous mental state occurs in patients who have at the onset of their seizures some “digestive” sensation—smell, epigastric sensations, taste, or in cases where there are movements implying excitation of centers for some such sensations, such movements as those of mastication. (15)

Postictal States

Hughlings-Jackson wrote extensively on postictal states, outlining many clinical cases. He appreciated the varieties of symptoms after seizures, ranging from “giddiness attended by trivial confusion of thought” to a “full violent seizure with universal convulsion and deep coma” (21).

In describing psychic symptoms, especially mania, in epileptic patients who had no discernible ictal event, he wrote,

In this and in every case of sudden mental automatism in epileptics there has been a prior slight and transient paroxysm. I believe there is in such cases, during the paroxysm, an internal discharge too slight to cause obvious external effects, but strong enough to put out of use for a time more of the highest nervous centres, because the highest or controlling centres have been thus put out of use. The automatism in these cases is not, I think, ever epileptic, but always post-epileptic. The condition after the paroxysm is duplex: 1) there is loss or defect of consciousness, and there is 2) mental automatism. In other words, there is 1) loss of control permitting 2) increased automatic action. (21)

In reference to the “dreamy state,” Hughlings-Jackson listed several scenarios of postictal actions, including continuance of actions ongoing before the seizure (“although in an imperfect and perhaps grotesque way”); disorientation and mild delirium, sometimes associated with wandering; the “so-called coordinated convulsion,” with struggling, shouting, and kicking, “often taken for hysteria”; and the patient’s becoming “violently maniacal” (15).

Hughlings-Jackson associated mania, as he did the symptom of the “dreamy state,” with epileptic seizures that impair consciousness as an initial manifestation:

Epileptic mania occurs in those epilepsies where loss of consciousness is either the first, or nearly the first, thing in the paroxysm; when there is “a warning” it is of a very general character. This is equivalent to saying that it occurs in those cases where the discharge begins in the very highest nervous processes. (20)

Cerebral Localization of the “Dreamy State”

In 1873, Hughlings-Jackson wrote about seizures characterized by a “sudden stench in the nose, with transient unconsciousness” (20). He stated that such symptoms were localizable but that he was unable to localize them at that time. Hughlings-Jackson eventually correlated the “dreamy state” and postmortem examination in several cases (including the case of Dr. Z [18]). In what proved to be some of the final publications of his career, through clinicopathological correlations he linked the “discharging lesion” of the “dreamy state” to the medial temporal region in what he called the “uncinate group of fits” (17). Of his localization of the “uncinate group of fits,” he wrote,

This was on the hypothesis that the discharge lesions in these cases are made up of some cells, not of the uncinate group alone, but of some cells of different parts of the region of which this gyrus is part—a very vague circumscription, I admit—the uncinate region. (17)

The “Dreamy State” and Neurological Function

As outlined above, Hughlings-Jackson described and localized the syndrome of medial temporal epilepsy with his descriptions of the “dreamy state.” However, his interest in the “dreamy state” went beyond the characterization of the syndrome. He saw the study of epilepsy as a key to understanding brain organization and function, stating, “No better neurologic work can be done than the precise investigation of epileptic paroxysms” (10). Integrating ideas from his study of neurological disease as a whole (but primarily from his study of the “dreamy state”) and his theories of organization of brain function, Hughlings-Jackson formulated his ideas about consciousness.

Laycock’s Doctrine of Reflex Function of the Brain

Hughlings-Jackson built on the ideas of Thomas Laycock, stating that all neurological functions relied on sensory and motor reflexes (20). The sensory and motor functions were represented most simplistically at the spinal ganglia, with phenomena such as the deep tendon reflex as an example. Hughlings-Jackson saw the brain as being regulated by laws identical to those governing the spinal ganglia. The brain, “although the organ of consciousness, is subject to the laws of reflex action, and…in this respect, it does not differ from the other ganglia of the nervous system.” Hughlings-Jackson also emphasized that higher nervous system function involved representations of sensory and motor processes rather than actual sensory and motor functions. The representation of sensory and motor processes he called “sensori-motor” function. “Sensori-motor” functions were represented and rerepresented, in greater complexity from the lowest to highest nervous system centers:

All nervous centres represent or re-represent impressions and movements. The highest centres are those which form the anatomical substrata of consciousness, and they differ from the lower centres in compound degree only. They represent over again, but in more numerous combinations, in greater complexity, specialty, and multiplicity of associations, the very same impressions and movements which the lower, and through them the lowest, centres represent. (20)

Evolution and Dissolution

Following the teachings of Herbert Spencer, Hughlings-Jackson proposed evolutionary levels of nervous system function (14). Functional levels increased in complexity and interconnectivity with evolution. A given function was represented and rerepresented at different levels, in its simplest form at the lowest level and its most complex form at the highest level (19). The clinical consequence of this hierarchical system was that CNS lesions induced both negative and positive neurological symptoms. A lesion (or “dissolution”) in the highest levels resulted not only in negative symptoms attributable to a loss of higher function but also in positive symptoms attributable to release of a lower level from inhibitory control. A clinical example is thalamic pain syndrome, where a loss of sensation represents a loss of a higher level of somatosensory function, while constant pain represents the unmasking or release of a lower level of function (5).

Degrees of Consciousness Represented by the “Dreamy State”

Hughlings-Jackson noted the clinical association of the “crude sensations” in epilepsy to loss of consciousness:

It is probable that the “aura” from the neighborhood of the epigastrum (sensation referred there, that is) is a crude and excessive development of visceral and other systemic sensations. However, if so, it seems strange that these sensations should, as is most common, occur in those cases of epilepsy in which loss of consciousness is, next to such warning, the first event in the paroxysm. (22)

Pulling together his ideas of the association of the “dreamy state,” the “crude sensations,” postictal symptoms, and loss of consciousness, Hughlings-Jackson proposed functioning levels of consciousness. He noted the disparity in the elaborateness of the “dreamy state” and the rudimentary nature of “crude sensations.” He thought of the symptom of the “dreamy state” as representing a higher degree of consciousness and “crude sensations” as representing a lower degree of consciousness.

Using the model of epilepsy, Hughlings-Jackson described three degrees of consciousness:

It seems to me evident that all three degrees should be considered in relation one to another. We may see all three in the same patient in connection with one full paroxysm. At or close to onset of the seizure he is defectively conscious, and he has the “dreamy state”; next he loses consciousness; when the paroxysm is over he is comatose. (14)

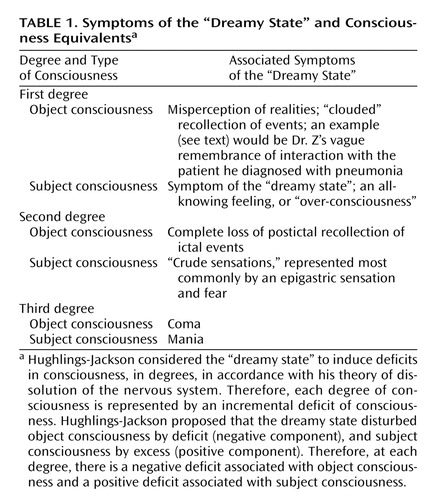

In keeping with his ideas about the positive and negative elements of dissolution, he proposed such elements in each degree. In the first degree the positive state was the “dreamy state,” while the negative state was a degree of loss of consciousness (realities misperceived). In the second degree the positive state was the “crude sensations,” while the negative state was complete loss of postevent recollection of ongoing ictal events. In the third degree the positive state was mania, and the negative state was coma (14, 23). Hughlings-Jackson also related the degrees of consciousness to his ideas of subject and object consciousness (Table 1).

Consciousness Defined

Hughlings-Jackson commented on the difficulties of defining consciousness, pointing out that the assessment of consciousness in an individual patient was subjective. He stated that observations can be made only on how one interacts with one’s environment, and that trying to affix a definite state of consciousness is a psychological and not a physiological question. Rather than defining consciousness, he emphasized that reestablishing phenomena associated with defects in consciousness was of much greater practical importance. He built his model of consciousness by studying deficits of consciousness in patients with diseases of the brain, using his theories of sensorimotor phenomena and dissolution. He expressed the advantages of this approach as follows:

This realistic method of treating the symptom loss of consciousness is a matter of the utmost importance. We can, on this method, study the “mental” as well as the “physical” symptoms of epilepsy anatomically and physiologically, and free from that psychological bias which makes the symptom loss, or trouble of consciousness, an isolated phenomenon, with no special relations to other nervous symptoms. (20)

Subject and Object Consciousness

Using his ideas of sensorimotor function, Hughlings-Jackson described two “halves” of consciousness, a subject half (representations of sensory function) and an object half (representations of motor function). To describe subject consciousness, he used the example of sensory representations when visualizing an object (23). The object is initially perceived at all sensory levels. This produced a sensory representation of the object at all sensory levels. The next day, one can think of the object and have a mental idea of it, without actually seeing the object. This mental representation is the sensory or subject consciousness for the object, based on the stored sensory information of the initial perception of it.

What enables one to think of the object? This is the other half of consciousness, the motor side of consciousness, which Hughlings-Jackson termed “object consciousness.” Object consciousness is the faculty of “calling up” mental images into consciousness, the mental ability to direct attention to aspects of subject consciousness. Hughlings-Jackson related subject and object consciousness as follows:

The substrata of consciousness are double, as we might infer from the physical duality and separateness of the highest nervous centres. The more correct expression is that there are two extremes. At the one extreme the substrata serve in subject consciousness. But it is convenient to use the word “double.” (20)

Hughlings-Jackson saw the two halves of consciousness as constantly interacting with each other, the subjective half providing a store of mental representations of information that the objective half used to interact with the environment.

Relationship of Subject and Object Consciousness to the “Dreamy State”

In relating consciousness to the “dreamy state,” it is important to understand that Hughlings-Jackson was referring to abnormalities of consciousness occurring during the ictal and postictal states—not interictal states, when there is presumably normal consciousness. He further defined the terms “subjective” and “objective,” relating them to symptoms of seizures, as follows:

The term “subjective” answers to what is physically the effect of the environment on the organism; the term “objective” to what is physically the reacting of the organism on the environment. Subjective sensations of smell and taste are the “most subjective” of the five senses. The epigastric sensation at the onset of seizures is hunger. All the crude sensations are psychical states, as indeed the term “sensation” implies. (19)

Hughlings-Jackson tied the ideas of subject and object consciousness to the degrees of consciousness represented by the “dreamy state”:

There often is, after a slight epileptic seizure (our first degree), a defect of object consciousness—so far negative—and positive remains of object consciousness with sometimes increase of subject consciousness, that is, “a dreamy state”—so far positive. In other words, “the positive condition” is itself duplex; it is an abnormal mental state; one imperfect by deficit and imperfect by excess. (14)

Expressed another way, Hughlings-Jackson saw a relative decrease in object consciousness and a relative increase in subject consciousness during the dreamy state; these represent changes in the first degree of consciousness. He did not describe the object and subject consciousness relationship of ictal phenomena at lower degrees, but one may infer that at the second degree of consciousness, the complete loss of postictal recollection of ictal events represents a further deficit of object consciousness, while the “crude sensations” represent an increase in the second degree of subject consciousness. At the third degree of consciousness, coma represents an even further deficit of object consciousness, while mania represents an increase of the lowest degree of subject consciousness. Table 1 lists the relationship of the signs and symptoms of the “dreamy state” to changes in degrees of consciousness.

Concomitance

Hughlings-Jackson recognized that his definition of brain function based on sensorimotor phenomena could not explain associated mental phenomena. In 1873, he wrote,

Why during the excitation of any set of sensori-motor processes, will, memory, etc., arise is unknown. The nature of the connection betwixt physiology and psychology is, so far as we can now see, an insoluble problem. (24)

Hughlings-Jackson developed his theory of concomitance to relate mental and nervous states. In 1884, he wrote,

Now I speak of the relation of consciousness to nervous states. The doctrine I hold is: first, that states of consciousness (or, synonymously, states of mind) are utterly different from nervous states; second, that the two things occur together—that for every mental state there is a correlative nervous state; third, that, although the two things occur in parallelism, there is no interference of one with the other. This may be called the doctrine of Concomitance. (23)

From his definition of concomitance, it is evident that Hughlings-Jackson considered epilepsy to affect the nervous state, which, through a different but parallel mechanism, produced a change in the mental state of consciousness.

Hughlings-Jackson and Freud

Hughlings-Jackson’s teachings about consciousness have influenced psychiatry. His writings about subject consciousness likely influenced Freud’s ideas of the “subconscious” as well as Freudian psychopathology (6, 25, 26) and continue to be applied today in discussions of psychiatric issues (27). The influence of Hughlings-Jackson’s writings on Freud must be inferred because Freud rarely credited any sources for his ideas (28). Before he wrote on the subject of psychoanalysis, Freud wrote a book on aphasia based on Hughlings-Jackson’s writings (28). As with most of his writings, Hughlings-Jackson’s articles on aphasia relate his neurological findings to his ideas of organization of the nervous system, including consciousness (6). Harrington (28) made a convincing argument for similarities of Hughlings-Jackson’s ideas of subject and object consciousness and Freud’s idea of primary/secondary thought, positing that the concept of “pathological subject consciousness” was the basis for Freud’s ideas about repression.

Contemporary Perspectives

Hughlings-Jackson’s description of the “dreamy state” describes the signs and symptoms of medial temporal epilepsy essentially as we understand them today. His postulations about a “discharging lesion” in the medial temporal region causing the symptoms also predate the current pathophysiologic concept of localization-related epilepsy. Subsequent developments of ictal electroencephalography recordings, however, have revealed one notable error in his postulations about symptoms in the “postictal” state. Hughlings-Jackson’s “mental automatisms” and “postictal actions” often begin during epileptic discharges and may or may not persist into the immediate postictal period (29). Whether positive symptoms in general, ranging from simple repetitive movements to the complex motor automatisms as presented in the history of Dr. Z, represent a direct activation of neuroanatomical structures from an epileptic discharge or are the result of a “release” allowing emergence of a lower degree of function remains an issue of debate (29, 30).

Hughlings-Jackson described “release” phenomena with his theory of evolution and dissolution of the nervous system, which is now often referred to as “hierarchies” of nervous system function (31). That positive symptoms occur during the ictal discharge of the seizure does not rule out a “release” phenomenon causing them, given the concept that discharging neurons are dysfunctional to some degree. Advances in functional neuroimaging, especially the emergence of ictal single photon emission tomography (SPECT), which enables measurement of ictal blood flow changes (which correlates with ictal electrical discharges [32]) over the entire brain, will likely help to resolve this issue (33). Consciousness in epilepsy has already come under study with ictal SPECT, and initial studies correlate loss of consciousness with secondary activation of bithalamic and upper brainstem structures (34).

A critical review of the concept of consciousness in epilepsy by Gloor (35) reveals an approach to defining consciousness that contrasts with Hughlings-Jackson’s approach. Gloor drew on epistemological and scientific arguments to attempt to define consciousness, which he admitted may never be possible, to illustrate that such definitions provide little to further our understanding of epilepsy. Hughlings-Jackson circumvented many of the difficulties in defining consciousness by using changes induced by neurological diseases (primarily epilepsy) to define it. Gloor described the complexity of consciousness and proposed that aspects of conscious experience such as perception, cognition, memory, affect, and voluntary motility are open to neurobiological research. The concept that consciousness is complex is very much in agreement with the ideas of Hughlings-Jackson. Indeed, Hughlings-Jackson’s conceptual framework for consciousness and epilepsy addresses many of the questions that Gloor raised. Especially relevant to psychiatry is the study of affective states.

As well described by Hughlings-Jackson, medial temporal epileptic seizures produce affective symptoms that are repeatedly and stereotypically seen in individual patients. The ictal and immediate postictal symptoms of medial temporal epilepsy, therefore, provide a pathophysiological model to study affective symptoms. Hughlings-Jackson’s description of the “dreamy state” integrates affective symptoms into an overall scheme of organization of the nervous system. The difficulty of interrelating “physical” and “mental” symptoms of consciousness, especially in the realm of affective symptoms, continues to be an important issue (36). Hughlings-Jackson proposed a method to do so, relating the “physical” and “mental” phenomena of the “dreamy state” with his theory of concomitance. The progression of Hughlings-Jackson’s thoughts about concomitance, in which he attempts to address the issue of “psychology versus physiology” in defining consciousness, mirrors the progression of modern neuroscientific thought, in which there is no longer a distinction between psychology and physiology. In the complex realm of defining consciousness (37), Hughlings-Jackson’s theories provide an interesting perspective for correlating brain function with mental function that may provide useful concepts for interpretation of modern investigations of human brain function, helping to better understand the functional basis of neuropsychiatric disease.

Of continued clinical interest is the issue of complex peri-ictal behavior. Of the complex peri-ictal behaviors, aggressive behavior is a particular concern. In a thorough review, Treiman (38) concluded that peri-ictal aggressive acts were stereotyped, simple, unsustained, and not supported by a consecutive series of purposeful movements. Treiman reported that “resistive violence,” where attempts to restrain patients still in a postictal confusional state produce violent reactive automatisms, is the most common phenomenon associated with aggressive behavior. He stated, “It is probable that such resistive violence occurs as a result of differential recovery of functional areas of the brain such that there is a relative delay in the recovery of pure motor functions.” The incidence of peri-ictal aggressive behavior is rare, but it occurs commonly enough to be a clinical concern (39). Most investigators emphasize that the clinical situation, especially reaction of bystanders during the peri-ictal state, is one of the most important factors in provoking aggressive behavior (38, 39).

Putting this phenomenon in the framework of Hughlings-Jackson’s classification of consciousness is helpful in understanding it. Hughlings-Jackson’s first degree of subject consciousness is associated with misperception of realities. Patients misperceive the intentions of bystanders during resistive violence and react to what they perceive as threatening behavior. A clear understanding of this phenomenon is important when evaluating patients with aggressive behavior, especially when the patient has a history of epilepsy.

Hughlings-Jackson not only described and localized medial temporal epilepsy but used his findings to help establish his theories of consciousness. His insightful description of the semiology of medial temporal epilepsy remains a useful reference. His innovative thoughts about its implications in consciousness provide an interesting model of brain function that remains relevant to contemporary ideas about consciousness. However, Hughlings-Jackson’s interrelation of the “dreamy state” and consciousness remains largely unrecognized. Further investigations of this relationship may continue to shed light on epilepsy as a model of brain function and elucidate the mind-brain relationship.

|

Received Feb. 11, 2002; revisions received Nov. 1, 2002, and April 10, 2003; accepted April 29, 2003. From the Greater Midwest Epilepsy Treatment Center, Department of Neurology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hogan, Greater Midwest Epilepsy Treatment Center, Department of Neurology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, 3635 Vista Ave. at Grand Blvd., St. Louis, MO 63110; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Tempkin O: John Hughlings Jackson, in The Falling Sickness: A History of Epilepsy From the Greeks to the Beginning of Modern Neurology. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971, pp 328–346Google Scholar

2. Reynolds EH: Hughlings Jackson and epilepsy: an introduction, in Hierarchies in Neurology: A Reappraisal of a Jacksonian Concept. Edited by Kennard C, Swash M. London, Springer-Verlag, 1989, pp 57–58Google Scholar

3. Critchley M, Critchley EA: The epilepsies, in John Hughlings Jackson: Father of English Neurology. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp 61–72Google Scholar

4. Taylor DC, Marsh SM: Hughlings Jackson’s Dr Z: the paradigm of temporal lobe epilepsy revealed. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1980; 43:758–767Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Steinberg DA, York GK: Hughlings Jackson, concomitance, and mental evolution. J Hist Neurosci 1994; 3:169–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Harrington A: The Hughlings Jackson perspective, in Medicine, Mind, and the Double Brain: A Study of Nineteenth-Century Thought. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1987, pp 206–234Google Scholar

7. Engelhardt HT: John Hughlings Jackson and the mind-body relation. Bull Hist Med 1975; 49:137–151Medline, Google Scholar

8. Eccles JC: Hughlings Jackson’s views on consciousness, in Hierarchies in Neurology: A Reappraisal of a Jacksonian Concept. Edited by Kennard C, Swash M. London, Springer-Verlag, 1989, pp 39–47Google Scholar

9. Kanemoto K: Epilepsy and recursive consciousness with special attention to Jackson’s theory of consciousness. Epilepsia 1998; 39:11–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hughlings-Jackson J: On a particular variety of epilepsy (“intellectual aura”), one case with symptoms of organic brain disease. Brain 1888; 11:179–207Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Blume WT, Luders HO, Mizrahi E, Tassinari C, Emde Boas W, Engel J Jr: ILAE Commission report: glossary of descriptive terminology for ictal semiology: report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2001; 42:1212–1218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wieser HG, Engel J Jr, Williamson PD, Babb TL, Gloor P: Surgically remediable temporal lobe syndromes, in Surgical Treatment of the Epilepsies. Edited by Engel J. New York, Raven Press, 1993, pp 49–63Google Scholar

13. Hughlings-Jackson J: Intellectual warnings of epileptic seizures, in The Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson, vol 1. Edited by Taylor J. New York, Basic Books, 1958, pp 274–275Google Scholar

14. Hughlings-Jackson J: Remarks on dissolution of the nervous system as exemplified by certain post-epileptic conditions, in The Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson, vol 2. Edited by Taylor J. New York, Basic Books, 1958, pp 3–28Google Scholar

15. Hughlings-Jackson J: Lectures on the diagnosis of epilepsy (Harveian Society), in The Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson, vol 1. Edited by Taylor J. New York, Basic Books, 1958, pp 276–307Google Scholar

16. Quaerens: A prognostic and therapeutic indication in epilepsy. The Practitioner 1870; 3:284–285Google Scholar

17. Hughlings-Jackson J, Stewart JP: Epileptic attacks with a warning of a crude sensation of smell and with the intellectual aura (dreamy state) in a patient who had symptoms pointing to gross organic disease of the right temporo-sphenoidal lobe. Brain 1899; 22:534–543Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Hughlings-Jackson J: Case of epilepsy with tasting movements and “dreamy state”—very small patch of softening in the left uncinate gyrus, in The Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson, vol 1. Edited by Taylor J. New York, Basic Books, 1958, pp 458–463Google Scholar

19. Hughlings-Jackson J: On right- or left-sided spasm at the onset of epileptic paroxysms and on crude sensation warnings and elaborate mental states. Ibid, pp 308–317Google Scholar

20. Hughlings-Jackson J: On the scientific and empirical investigation of epilepsies. Ibid, pp 162–273Google Scholar

21. Hughlings-Jackson J: On temporary mental disorders after epileptic paroxysms. Ibid, pp 119–134Google Scholar

22. Hughlings-Jackson J: Remarks on systemic sensations in epilepsies. Ibid, p 118Google Scholar

23. Hughlings-Jackson J: Evolution and dissolution of the nervous system (Croonian Lectures), in The Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson, vol 2. Edited by Taylor J. New York, Basic Books, 1958, pp 45–75Google Scholar

24. Hughlings-Jackson J: On the anatomical, physiological, and pathological investigations of epilepsies, in The Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson, vol 1. Edited by Taylor J. New York, Basic Books, 1958, pp 90–111Google Scholar

25. Freud S: The Interpretation of Dreams (1900): Complete Psychological Works, standard ed, vols 4, 5. London, Hogarth Press, 1953Google Scholar

26. Critchley M, Critchley EA: Jackson’s achievements assessed by other neurologists, in John Hughlings Jackson: Father of English Neurology. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp 147–156Google Scholar

27. Meares R: The contribution of Hughlings Jackson to an understanding of dissociation. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1850–1855Abstract, Google Scholar

28. Harrington A: Freud and Jackson’s double brain: the case for a psychoanalytic debt, in Medicine, Mind, and the Double Brain: A Study of Nineteenth-Century Thought. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1987, pp 235–247Google Scholar

29. Kotagal P: Automotor seizures, in Epileptic Seizures: Pathophysiology and Clinical Semiology. Edited by Lüders HO, Noachtar S. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 2000, pp 449–457Google Scholar

30. Gloor P: The amygdaloid system, in The Temporal Lobe and Limbic System. New York, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp 591–721Google Scholar

31. Kennard C, Swash M (eds): Hierarchies in Neurology: A Reappraisal of a Jacksonian Concept. London, Springer-Verlag, 1989Google Scholar

32. Spanaki MV, Zubal IG, MacMullan J, Spencer SS: Periictal SPECT localization verified by simultaneous intracranial EEG. Epilepsia 1999; 40:267–274Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Spencer SS: Neural networks in human epilepsy: evidence of and implications for treatment. Epilepsia 2002; 43:219–227Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Lee KH, Meador KJ, Park YD, King DW, Murro AM, Pillai JJ, Kaminski RJ: Pathophysiology of altered consciousness during seizures: subtraction SPECT study. Neurology 2002; 59:841–846Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Gloor P: Consciousness as a neurological concept in epileptology: a critical review. Epilepsia 1986; 27(suppl 2):S14-S26Google Scholar

36. Chalmers DJ: The problems of consciousness, in Consciousness: At the Frontiers of Neuroscience. Edited by Jasper HH, Descarries L. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1998, pp 1–18Google Scholar

37. Zeman A: Consciousness. Brain 2001; 124:1263–1289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Treiman DM: Epilepsy and violence: medical and legal issues. Epilepsia 1986; 27(suppl 2):S77-S104Google Scholar

39. Fenwick P: The nature and management of aggression in epilepsy. J Neuropsychiatry 1989; 1:418–424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar