A Randomized Trial of Sertraline as a Cessation Aid for Smokers With a History of Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Evidence that major depression can be a significant hindrance to smoking cessation prompted this examination of the usefulness of sertraline as a cessation aid for smokers with a history of major depression. Specifically, sertraline’s efficacy for smoking abstinence and its effects on withdrawal symptoms were evaluated. METHOD: The study design included a 1-week placebo washout, a 9-week double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment phase followed by a 9-day taper period, and a 6-month drug-free follow-up. One hundred thirty-four smokers with a history of major depression were randomly assigned to receive sertraline (N=68) or matching placebo (N=66); all received intensive individual cessation counseling during nine clinic visits. RESULTS: Sertraline treatment produced a lower total withdrawal symptom score and less irritability, anxiety, craving, and restlessness than placebo. However, the abstinence rates did not significantly differ between treatment groups: 28.8% (19 of 66) for placebo and 33.8% (23 of 68) for sertraline at the end of treatment and 16.7% (11 of 66) for placebo and 11.8% (eight of 68) for sertraline at the 6-month follow-up. No moderating effects of single or recurrent major depression, depressed mood at baseline, nicotine dependence level, or gender were observed. CONCLUSIONS: Sertraline did not add to the efficacy of an intensive individual counseling program in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. However, given that the end-of-treatment abstinence rate for the placebo group was much higher than expected, it is unclear whether a ceiling effect of the high level of psychological intervention received by all subjects prevented an adequate test of sertraline.

Smokers with a history of major depression are known to experience great difficulty when they attempt to stop smoking. They often have lower cessation rates and, when they are able to stop smoking, experience more severe withdrawal symptoms and higher incidences of depressed mood and of new episodes of major depression during the postcessation period than do smokers who do not have a history of major depression (1). Prompted by that knowledge, we conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to test the efficacy of sertraline as a cessation aid for smokers with a history of major depression. Sertraline is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) with proven efficacy for alleviating depressive disorders (2). This hypothesis is in line with observations from two independent trials of fluoxetine (3, 4), also an SSRI, that showed an apparent benefit of the drug among smokers who manifested at least subclinical levels of depression before cessation, although not among smokers without depressed mood at baseline.

In addition, on the basis of indications from earlier epidemiological (5) and clinical (6) data that the effect of major depression history on cessation rate occurs primarily among those who have experienced multiple episodes of major depression, we further hypothesized that sertraline efficacy would be more apparent among smokers with a history of recurrent major depression than among those who reported a single prior episode.

The prospective nature of the study design also permitted an investigation of sertraline’s effect on the intensity of withdrawal symptoms. It was expected that sertraline use would be associated with less discomfort during the first week after the quit day.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were required to meet the DSM-III-R criteria for at least one episode of major depression, which must have remitted more than 6 months before the start of the study. Additional entry criteria were age between 18 and 70 years, daily use of 20 or more cigarettes for at least 1 year, and at least one prior attempt to stop smoking. The exclusion criteria were serious medical illness; use of a psychotropic medication, major depression, alcohol or drug dependence, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anorexia nervosa, or bulimia nervosa within the past 6 months; lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder, antisocial or schizotypal personality disorder, severe borderline personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or psychosis including schizophrenia; and pregnancy or lactation.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Participants were recruited through newspaper and other print advertisements in the New York metropolitan area. To avoid false reporting of a history of major depression by volunteers in order to qualify for the study, these advertisements did not mention that a history of major depression was an entry criterion. The respondents were first screened by telephone, and those who met the initial criteria with respect to smoking and past major depression were seen at an initial clinic visit. The study procedures were fully explained by the study physician (K.S.) to each prospective participant, who then indicated informed consent by signing the informed consent form approved by the institutional review board for this particular study. A medical and psychiatric history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, and blood chemistry screen were then performed to ensure that the participant fulfilled all entry criteria. Participants were seen from October 1993 to January 1997.

Study Protocol

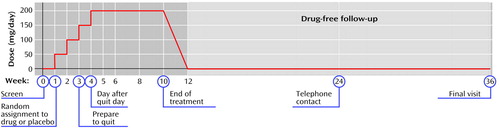

The schedule of study procedures is shown in Figure 1. Participants who were considered eligible on the basis of the information obtained at the screening visit began a 1-week single-blind washout phase of one placebo tablet per day. After 1 week, subjects whose medical eligibility was confirmed by the laboratory tests were randomly assigned in double-blind fashion to receive sertraline (in 50-mg tablets) or matching placebo pills. Medications were provided in prepared bottles that were numbered according to the randomization schedule and dispensed at each visit. All study staff at the clinic site were blinded to treatment assignment. Compliance with the medication schedule was assessed by pill counts at each visit.

At the visit when random assignment took place (week 1), the subjects were instructed to continue taking a single morning dose of the medication (placebo or 50 mg of sertraline) during the following week and to increase their study medication by 1 tablet each week for the next 2 weeks; that is, patients in the sertraline group received 100 mg/day through week 2 and 150 mg/day through week 3. At week 3, each subject was asked to select a target quit day that would fall approximately 7 days later. The subjects were encouraged to reduce the number of cigarettes they smoked as they approached the quit day and instructed to stop smoking completely as of that quit day. Until week 3, the subjects had been asked to maintain their pretreatment level of smoking.

Each subject returned for a clinic visit on the day following the quit day. On the assumption that a subject’s failure to reduce smoking to 50% of his or her baseline level indicated a lack of the motivation level required to stop smoking, subjects who did not meet this cutoff were removed from the study. The subjects who remained were then instructed to increase their medication dose to 4 tablets (200 mg/day of sertraline) and to continue this dose for the next 6 weeks. At the end of that period, the subjects tapered the study medication by 1 tablet (50 mg of sertraline) every 3 days and returned for a posttreatment clinic visit in 2 weeks. In sum, the subjects were required to take the study medication for 11.3 weeks: 1 week of placebo washout, 3 weeks for medication buildup before the quit day, 6 weeks at full dose (200 mg/day of sertraline), and a 9-day taper period. All subjects entered a 6-month follow-up phase; they were contacted by telephone 3 months after the end of treatment and asked to return to the clinic at 6 months.

Counseling

The participants were seen at each of the nine clinic visits by an experienced therapist (L.S.C. or F.S.) and monitored for adverse reactions by a study psychiatrist (K.S. or A.H.G.). The counseling protocol, described in detail elsewhere (7), incorporated standard smoking cessation techniques (i.e., orientation to the health risks of smoking and benefits of cessation, skills training for coping with withdrawal symptoms and avoiding relapse) and was augmented by a supportive approach designed to help the smoker recognize, express, and manage negative affects related to the effort to quit. We took this extra step in the counseling process in an attempt to reduce withdrawal symptoms, since these have been reported to be more severe and predictive of cessation failure among smokers with a history of major depression (8–10). The counseling sessions typically lasted 45 minutes.

Measures

The main study outcome was point-prevalence rate of abstinence during the preceding 7 days, ascertained by self-report at each clinic visit (and by telephone at month 3 during the follow-up phase). These reports were biologically verified (by a serum cotinine level less than 25 ng/ml) at the end of treatment and at the visit at the end of the 6-month follow-up. The subjects lost to follow-up after random assignment were considered treatment failures. To assess current major depression (an exclusion criterion) or past history of major depression (an entry requirement), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (11) was administered. Interrater tests conducted with 10 subjects to monitor the reliability of the diagnostic assessments indicated substantial agreement between the raters (L.S.C. and F.S.). Nicotine dependence level was measured by the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (12). Depressed mood at baseline was measured by using the Beck Depression Inventory (13), the Center for Epidemiology Depression Scale (CES-D Scale) (14), and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (15). Withdrawal symptoms (craving, irritability, anxiety, restlessness, concentration difficulty, depressed mood, appetite increase, and sleep disturbance) were rated at each clinic visit by using a 6-point rating scale (0=none, 5=extreme).

Statistical Analysis

Given the number of subjects, we had 85% power to detect a statistically significant (alpha=0.05, two-tailed test) difference between drug and placebo with estimated end-of-treatment abstinence rates of 15% for placebo and 40% for sertraline. The estimate for placebo is based on that observed among placebo-treated smokers with past major depression seen in an earlier study by our group (16); the estimate for sertraline is a conservative estimate based on the 50% end-of-treatment abstinence rate among smokers with past major depression who were treated with the experimental drug (clonidine) in the previous study (16).

Chi-square tests and t tests were used to assess the significance of differences between the placebo- and sertraline-treated subjects. The general linear model procedure in SPSS 10.0 for Windows (Chicago, SPSS) was used to test the effects of sertraline, relative to those of placebo, on change in symptom ratings between the week before the quit day and the end of the first week after the quit day. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 (two-tailed tests).

Results

Subject Flow

Of the 161 subjects seen for a screening visit, 27 (16.8%) did not meet the full entry criteria. The remaining 134 began a 1-week placebo-washout phase. At their next clinic visit, the subjects were randomly assigned to receive placebo (N=66) or sertraline (N=68). Of these 134 subjects, 25.4% (N=34) dropped out of the study before their selected quit day. More of the early terminations occurred in the placebo group (19 of 66, 28.8%) than in the sertraline group (15 of 68, 22.1%), although not at a statistically significant level (χ2=0.80, df=1, p>0.30). Of these 34 early dropouts, 13 (eight receiving placebo and five receiving sertraline) were unable to cut down below 50% of their baseline smoking levels by the quit day and, following the study protocol, did not continue in the study; seven (three receiving placebo, four receiving sertraline) dropped out because of adverse reactions (dizziness, agitation, spaciness, diarrhea); two (one receiving placebo, one receiving sertraline) suffered a stressful event unrelated to the treatment; and 12 (seven receiving placebo, five receiving sertraline) withdrew consent, citing a loss of motivation to quit smoking.

Subject Characteristics

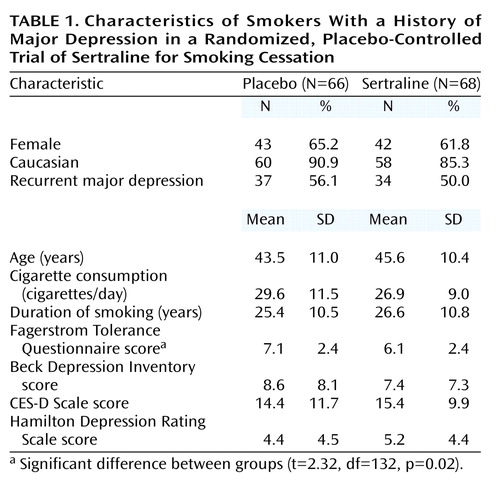

Of the 134 subjects randomly assigned to treatment, 47.0% (N=63) reported a history of recurrent major depression. The mean age was 44.5 years (SD=10.7); 87.3% were white (N=117), and 33.6% were married (N=45). All had tried to quit smoking at least once in the past. The mean number of cigarettes smoked daily was 28.2 (SD=10.4), the mean duration of smoking was 26.0 years (SD=10.7), and the mean score on the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire was 6.5 (SD=2.4). The mean baseline scores on the scales measuring depressed mood at baseline were suggestive of moderate, but not diagnostic, depression: 8.0 (SD=7.7) on the Beck Depression Inventory, 14.9 (SD=10.8) on the CES-D Scale, and 4.8 (SD=4.4) on the Hamilton depression scale. A comparison of subjects on these characteristics by treatment assignment (Table 1) showed a lower mean Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire score for the subjects who received sertraline, but no differences on other variables.

Withdrawal Symptoms

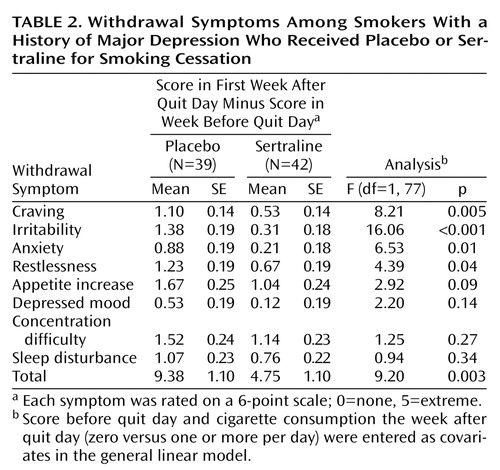

Withdrawal symptoms were measured as the change between symptom ratings at the end of the week immediately before the quit day and at the end of the first week after the quit day. Data from 81 subjects (39 taking placebo, 42 taking sertraline) who returned for a clinic visit 1 week after the quit day were available for this analysis. Symptom ratings for the week before the quit day and abstinence status during the week after the quit day (zero versus one or more cigarettes per day) were entered as covariates in these analyses. Symptom ratings at later visits were not examined because of the increase in missing information as more subjects dropped out. As shown in Table 2, increases occurred for all symptoms regardless of treatment, but statistically significant differences between treatment conditions were observed only for craving, irritability, anxiety, and restlessness. Some difference in appetite increase was observed, but unimpressive differences were observed for depressed mood, concentration difficulty, and sleep disturbance. The difference between treatments in the summed withdrawal score was also statistically significant.

Cessation Outcome

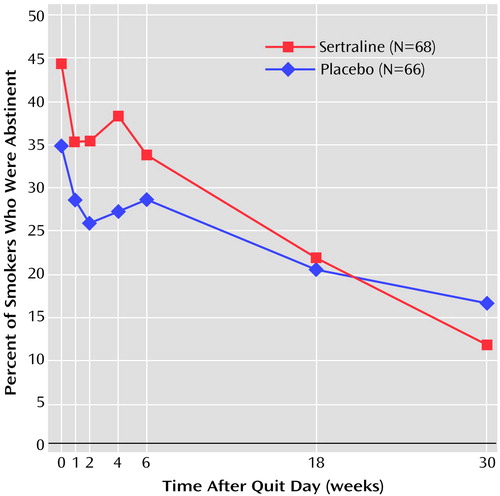

In keeping with the intent-to-treat strategy, the data shown in Figure 2 are based on all 134 subjects who were randomly assigned to placebo or sertraline. The point-prevalence cessation rates during the active treatment period or the drug-free follow-up did not markedly differ by medication status. At the end of treatment, the abstinence rates were 28.8% (19 of 66) for placebo and 33.8% (23 of 68) for sertraline (χ2=0.39, df=1, p=0.53); 6 months later, the rates were 16.7% (11 of 66) and 11.8% (eight of 68), respectively (χ2=0.66, df=1, p=0.42). Had the end-of-treatment cessation rate among the placebo-treated group been at or around our initial estimate of 15%, the observed sertraline success rate of 33.8% would have provided 85% power for detecting a statistically significant (p=0.05) drug-placebo difference with a one-tailed test and 70% power for a two-tailed test.

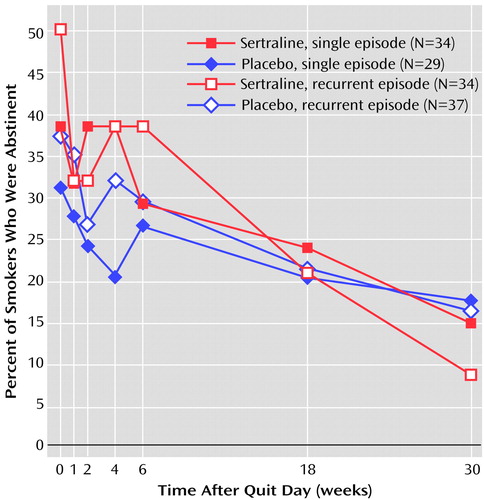

Further analysis of drug effects by depression subtype, single-episode versus recurrent, did not indicate an interaction (Figure 3). No modifying effect of depressed mood at baseline (as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory, CES-D Scale, or Hamilton depression scale), nicotine dependence level (despite a lower score on the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire among the sertraline-treated subjects), or gender was observed (data available from the authors).

We performed an alternative data analysis that was limited to subjects who remained in the study until the quit day (47 in the placebo group, 53 in the sertraline group) and, following the study protocol, raised their dose to 200 mg/day for the duration of their participation in the study. The same negative outcome was observed. The proportions of abstainers at the end of treatment and at the 6-month follow-up were not markedly different between the placebo and sertraline groups. At end of treatment, these rates were 40.4% (19 of 47) for placebo and 43.4% (23 of 53) for sertraline (χ2=0.09, df=1, p>0.70). At 6 months, the rates were 23.4% (11 of 47) and 15.1% (eight of 53), respectively (χ2=1.12, df=1, p>0.20).

Discussion

Studies of addiction treatment have increasingly demonstrated that the associated withdrawal symptoms are manageable with appropriate medication (17). Our finding that sertraline reduces the intensity of withdrawal symptoms is consistent with that belief. Unfortunately, that salutary effect of sertraline did not extend to cessation itself in the present study. Despite slightly higher abstinence rates for sertraline during the first several weeks after the quit day (Figure 3), these rates converged to 33.8% for sertraline and 28.8% for placebo by the end of the active treatment period.

The absence of a treatment effect persisted during the 6-month drug-free follow-up phase. Further data analysis did not indicate a difference in trend by single-episode versus recurrent subtype of major depression (Figure 3) or by other putative predictors of abstinence (Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire score, number of cigarettes per day, depressed mood, gender). Because these negative results contradict our empirically based hypotheses regarding the usefulness of antidepressant medication for smokers with a history of depression and also do not correspond with published findings on fluoxetine for smokers with depressed mood (3, 4), we will discuss possible reasons for our finding on sertraline and cessation outcome and factors that challenge the validity of that finding.

Sertraline is only one of several antidepressant medications that have been tested as treatments for tobacco dependence. This line of research was founded on observations regarding the deleterious influence of depressed mood (18, 19) and major depressive disorder (16) on cessation. Of the antidepressants that have been tested, only bupropion (20, 21) and nortriptyline (22) have convincingly demonstrated efficacy for smoking cessation. Furthermore, contrary to expectations, bupropion and placebo did not exert differential effects on depressed mood during the withdrawal period (20), and the positive effect of nortriptyline was observed irrespective of a history of depression (22). Fluoxetine, on the other hand, yielded largely negative results in a large-scale multisite trial of smokers (J.S. Mizes et al., unpublished study, 1996). Nevertheless, supporting our initial expectations, two reports from placebo-controlled trials of fluoxetine (3, 4) contained data suggesting some advantage of the drug among smokers with elevated scores on scales measuring depressed mood. The first of these studies (4) used subjects from selected sites in the multisite fluoxetine study reported by Mizes and colleagues and examined the likelihood of abstinence as a function of baseline score on the Hamilton depression scale. While no main effect of fluoxetine was observed in the intent-to-treat analysis, further examination among subjects who were compliant with the treatment protocol indicated increasing efficacy of fluoxetine relative to placebo with increasing scores on the Hamilton depression scale (3). Similarly, in 12-month data from a placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine plus a nicotine inhaler, Blondal and colleagues (3) also found no evidence that fluoxetine improved abstinence among unselected smokers; however, among high scorers on the Beck Depression Inventory, the researchers found a higher abstinence rate in the fluoxetine group than in the placebo group. Trials of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin (23) and of moclobemide, a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (24), have also been conducted, but these produced weak effects and as yet do not have the benefit of replication.

Characteristics of study design may partly account for some of the inconsistencies among study findings, but additional reasons may lie in the interface of antidepressant compounds and the complex neurobiology of tobacco dependence. For instance, bupropion and nortriptyline, which produced positive results, are known to affect dopaminergic and adrenergic neurons, while fluoxetine and sertraline affect primarily the serotonergic system. That negative results with respect to cessation have been observed with fluoxetine and now sertraline raises questions regarding the importance of serotonin in tobacco or nicotine dependence.

Conversely, we considered reasons that may have falsely led to the absence of a sertraline-placebo difference. Had we overdiagnosed the presence of a history of major depression? Were the cessation rates for placebo so similar to those for sertraline because of a placebo effect? Or were the cessation rates for the active drug so similar to placebo because of a ceiling effect?

With respect to the problem of diagnostic error, we are inclined to regard this as a small threat, having taken pains to prevent its occurrence from the outset. The diagnostic assessments were performed by experienced psychiatric interviewers (L.S.C. and F.S.); in cases of uncertainty, the subject was reinterviewed by the study psychiatrist (A.H.G. or K.S.), and a diagnosis of major depression was made only when consensus among the raters was obtained. In further support of the diagnostic composition of the study group, we note that, as reported in an earlier article (25), we observed a 31% incidence of new major depressive episodes during the follow-up period among the abstinent smokers in the present group. This incidence of postcessation depression is much higher than would be expected from smokers without a history of major depression and is congruent with findings by Tsoh et al. (26) and by our group (27) that substantial proportions of abstainers with a history of major depression are at risk of new episodes of major depression after an attempt to quit smoking.

The placebo effect is an improved response because subjects think they are receiving the active medication. We do not have direct evidence relating to this issue since the impressions regarding treatment received were not systematically obtained from the subjects or from the counselors. Nevertheless, as discussed by Quitkin et al. (28), the placebo effect is distinguishable from a true drug response in that it is short-lived, usually fading after 2 weeks. By contrast, the lack of placebo-sertraline differences in abstinence rates that began during the first week after the quit day continued through the 10 weeks of treatment and extended to the drug-free 6-month follow-up period. This evidence of persistence argues against a placebo effect.

The ceiling effect, as discussed by Paykel (29) in comparisons of psychotherapy with medication treatment, occurs when no additional benefit from a second treatment is observed in the presence of an effective treatment. In the present study, because our counseling approach was intense in both content (a psychotherapeutic approach) and duration (45 minutes during nine clinic visits), we wondered whether it had comprised another active treatment and, even without the benefit of pharmacotherapy, resulted in a higher-than-expected cessation rate. Indeed, the cessation rates among the placebo-treated subjects in the present study group were higher than those we observed in two earlier studies in which the level of counseling support had been minimal and brief (6, 16). In the first study (16), the end-of-treatment success rate for placebo in smokers with past major depression was 13.6% (three of 22 subjects); in contrast, the end-of-treatment placebo rate in the present study was 28.8% (19 of 66). In the second study, where the recurrent and single forms of major depression were separated (6), the end-of-treatment placebo success rate among subjects with recurrent major depression was 8.0% (two of 25), whereas the corresponding placebo success rate in the present study was, again, markedly higher, 29.7% (11 of 37). It is notable that others have observed the particular efficacy of psychological counseling for smokers with past major depression (22) and alcohol disorder (30). Also relevant is the finding by Brown and colleagues (31) that cognitive behavior therapy for depression produced a cessation rate superior to that of a standard counseling protocol for smokers with a history of recurrent major depression. If a ceiling effect did occur, there are a number of implications. First, the study, as implemented, did not permit a valid comparison of sertraline with an appropriate inactive treatment; second, the efficacy of sertraline remains open to question; and third, since only a minority (about 30%) of the total study group succeeded in stopping smoking despite the high level of intervention they received, it is apparent that treatments other than those offered in our study were needed by this target group of smokers with a history of major depression. It is also noteworthy that the presumed advantage of the 9-week intensive psychological counseling did not persist beyond the treatment period, as only half of the end-of-treatment abstainers were still not smoking 6 months later.

The positive effect of sertraline on withdrawal symptoms despite the lack of benefit on cessation itself is intriguing. It contrasts with the evidence on nicotine replacement therapy (32, 33) and bupropion (34) that indicates positive effects of those agents on reduction of withdrawal symptoms as well as cessation. However, there are other medications that have also been observed to ameliorate withdrawal symptoms but were not found to improve cessation better than placebo. Examples are buspirone (35) and paroxetine (36). This finding implies that the intensity of withdrawal symptoms during the first week of treatment may not be a reliable surrogate in determining the promise of a new treatment. Hughes (37) has suggested that duration of withdrawal symptoms may be a better predictor.

Contravening a promising theoretical rationale as well as prior observations with fluoxetine for smokers with depressed mood (3, 4), this clinical trial did not provide encouraging evidence for sertraline as a cessation treatment for smokers with past major depression. However, the negative finding occurred in the context of a placebo cessation rate that was much higher than expected, raising the possibility that the intense level of concomitant psychological intervention received by all subjects prevented an adequate test of the active treatment. The additional finding that sertraline reduced withdrawal symptoms is noteworthy since this apparent advantage did not extend to cessation, a phenomenon observed as well for other, although not all, pharmacotherapies for tobacco dependence. These observations regarding sertraline and the ostensible value of intensive psychological counseling warrant consideration in future trials of candidate treatments for tobacco dependence.

|

|

Presented in part at the 6th Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Feb. 18–20, 2000, Arlington, Va. Received Feb. 19, 2002; revision received April 23, 2002; accepted April 24, 2002. From the New York State Psychiatric Institute; and the Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Covey, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). Pfizer, Inc., provided support for conducting the study. Preparation of this article was supported in part by grant DA-13490 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Figure 1. Phases of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Sertraline for Smoking Cessation by 134 Smokers With a History of Major Depressiona

aThe patients who received placebo followed the same schedule but received placebo pills instead of sertraline.

Figure 2. Rate of Smoking Cessation After Quit Day Among Smokers With a History of Major Depression Who Received Sertraline or Placebo

Figure 3. Rate of Smoking Cessation After Quit Day Among Smokers With a History of Single-Episode or Recurrent Major Depression Who Received Sertraline or Placebo

1. Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F: Cigarette smoking and major depression. J Addict Disord 1998; 17:35-46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. McQueen G, Born L, Steiner M: The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline: its profile and use in psychiatric disorders. CNS Drug Rev 2001; 7:1-24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Blondal T, Gudmundsson LJ, Tomasson K, Jonsdottir D, Hilmarsdottir H, Kristjansson F, Nilsson F, Bjornsdottir US: The effects of fluoxetine combined with nicotine inhalers in smoking cessation—a randomized trial. Addiction 1999; 94:1007-1015Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hitsman B, Pingitore R, Spring B, Mahableshwarkar A, Mizes JS, Segraves KA, Kristeller JL, Xu W: Antidepressant pharmacotherapy helps some cigarette smokers more than others. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999; 67:547-554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Covey LS, Hughes D, Glassman AH, Blazer D, George LK: Ever smoking, quitting, and psychiatric disorders: evidence from the Durham Epidemiological Catchment Area. Tob Control 1994; 3:222-227Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Glassman AH, Covey LS, Dalack GW, Stetner F, Rivelli SK, Fleiss J, Cooper TB: Smoking cessation, clonidine, and vulnerability to nicotine among dependent smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1993; 54:670-679Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Covey LS: A psychotherapeutic approach for smoking cessation counseling, in Helping the Hard-Core Smoker: A Clinician’s Guide. Edited by Seidman DF, Covey LS. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1999, pp 175-193Google Scholar

8. Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F: Depression and depressive symptoms in smoking cessation. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:350-354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P: Nicotine withdrawal symptoms and psychiatric disorders: findings from an epidemiologic study of young adults. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 149:464-469Google Scholar

10. Hughes JR: Tobacco withdrawal in self-quitters. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:689-697Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Instruction Manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1988Google Scholar

12. Fagerstrom KO: Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav 1978; 3:235-241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561-571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Applied Psychol Measurement 1977; 1:385-401Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Glassman AH, Stetner FS, Walsh BT, Raizman P, Cooper T, Covey LS: Heavy smokers, smoking cessation, and clonidine: results of a double-blind, randomized trial. JAMA 1988; 259:2863-2866Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Leshner AI: Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science 1997; 279:45-47Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Anda RF, Williamson DF, Escobedo LG, Mast EE, Giovino GA, Remington PL: Depression and the dynamics of smoking: a national perspective. JAMA 1990; 262:1541-1545Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F: Depression and depressive symptoms in smoking cessation. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:350-354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hurt RD, Sachs DL, Glover ED, Offord KP, Johnston JA, Dale LC, Khayrallah MA, Schroeder DR, Glover PN, Sullivan CR, Croghan IT, Sullivan PM: A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1195-1202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, Rennard SJ, Johnston JA, Hughes AR: A controlled trial of sustained release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:685-691Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Hall SM, Reus VI, Muñoz RF, Sees KL, Humfleet G, Hartz DT, Frederick S, Triffleman E: Nortriptyline and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of cigarette smoking. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:683-690Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Edwards NB, Simmons RC, Rosenthal TL, Hoon PW, Downs JM: Doxepin in the treatment of nicotine withdrawal. Psychosomatics 1988; 29:203-206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Berlin I, Said S, Spreux-Varoquaux O, Launay JM, Olivares R, Millet V, Lecrubier Y, Puech AJ: A reversible monoamine oxidase A inhibitor (moclobemide) facilitates smoking cessation and abstinence in heavy, dependent smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1995; 58:444-452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Glassman AH, Covey LS, Stetner F, Rivelli S: Smoking cessation and the course of major depression: a follow-up study. Lancet 2001; 357:1929-1932Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Tsoh JY, Humfleet GL, Muñoz RF, Reus VI, Hartz DT, Hall SM: Development of major depression after treatment for smoking cessation. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:368-374; correction, 157:1359Link, Google Scholar

27. Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F: Major depression following smoking cessation. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:263-265Link, Google Scholar

28. Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Rabkin JG, Stewart JW, Harrison W, Ross DC, Tricamo E, Fleiss J, Markowitz J, Klein DF: Different types of placebo response in patients receiving antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:197-203Abstract, Google Scholar

29. Paykel ES: Psychotherapy, medication combinations, and compliance. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56(suppl 1):24-30Google Scholar

30. Patten CA, Martin JE, Myers MG, Calfas KJ, Williams CD: Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for smokers with histories of alcohol dependence and depression. J Stud Alcohol 1998; 59:327-335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Brown RA, Kahler CW, Niaura R, Abrams DB, Sales SD, Ramsey SE, Goldstein MG, Burgess ES, Miller IW: Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001; 69:471-480Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Abelin T, Buehler A, Muller P, Vesanen K, Imhof PR: Controlled trial of transdermal nicotine patch in tobacco withdrawal. Lancet 1989; 1:7-10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Fiore MC, Kenford SL, Jorenby DE, Wetter DW, Smith SS, Baker TB: Two studies of the clinical effectiveness of the nicotine patch with different counseling treatments. Chest 1994; 105:524-533Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Shiffman S, Johnston JA, Khayrallah M, Elash CA, Gwaltney CJ, Paty JA, Gnys M, Evoniuk G, DeVeaugh-Geiss J: The effect of bupropion on nicotine craving and withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000; 148:33-40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Robinson MD, Pettice YL, Smith WA, Cederstrom EA, Sutherland DE: Buspirone effect on tobacco withdrawal symptoms: a randomized placebo controlled trial. J Am Board Fam Pract 1992; 5:1-9Medline, Google Scholar

36. Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Schatzberg AF, Hayward C, Sussman L, Rothman M, Strausberg L, Varady A: Nicotine patch and paroxetine for smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:883-889Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Hughes JR: Why does smoking so often produce dependence? a somewhat different view. Tob Control 2001; 10:62-64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar