Depressive Symptoms, Satisfaction With Health Care, and 2-Year Work Outcomes in an Employed Population

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The relationship of depressive symptoms, satisfaction with health care, and 2-year work outcomes was examined in a national cohort of employees. METHOD: A total of 6,239 employees of three corporations completed surveys on health and satisfaction with health care in 1993 and 1995. This study used bivariate and multivariate analyses to examine the relationships of depressive symptoms (a score below 43 on the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey mental component summary), satisfaction with a variety of dimensions of health care in 1993, and work outcomes (sick days and decreased effectiveness in the workplace) in 1995. RESULTS: The odds of missed work due to health problems in 1995 were twice as high for employees with depressive symptoms in both 1993 and 1995 as for those without depressive symptoms in either year. The odds of decreased effectiveness at work in 1995 was seven times as high. Among individuals with depressive symptoms in 1993, a report of one or more problems with clinical care in 1993 predicted a 34% increase in the odds of persistent depressive symptoms and a 66% increased odds of decreased effectiveness at work in 1995. There was a weaker association between problems with plan administration and outcomes. CONCLUSIONS: Depressive disorders in the workplace persist over time and have a major effect on work performance, most notably on “presenteeism,” or reduced effectiveness in the workplace. The study’s findings suggest a potentially important link between consumers’ perceptions of clinical care and work outcomes in this population.

As of 1996, 149 million Americans, or more than 93% of those with private insurance, received that insurance through employers (1). This “accidental” employer-based insurance system arose less by explicit design than as a byproduct of federal laws and tax incentives enacted during the years since World War II (2, 3). Nonetheless, employers have remained the predominant purchasers of private health insurance in the United States, even during a time in which managed care has transformed the organization and practice patterns of health care providers (4). Under such a system, the choice among health plans is often made by employers or strongly influenced by employer decisions (5). From the perspective of an employer-purchaser, the value of a health benefits package lies in its ability not only to attract and retain good workers but also to reduce illness-related absenteeism and to improve workplace productivity (6).

In this study we used a longitudinal survey of more than 6,000 employees to examine the relationship of depression, satisfaction with health care, and work outcomes. We tested the hypotheses that depressive illness is associated with persistent difficulties in workplace functioning and that consumer-reported problems in health care explain a portion of those work difficulties among depressed individuals.

Method

This study used data collected for a longitudinal quality improvement project conducted in three major U.S. corporations. The first phase, the Employee Health Care Value Survey, was a 154-item questionnaire completed by a total of 14,587 employees in 1993 (7). The second phase, a 116-item survey, was mailed in 1995 to a random sample of 9,294 of the employees who had responded to the first survey and who were still employed by the corporations (8). The four-step mail procedure (9) yielded a 63.5% response rate in 1993 and a 67.1% response rate in 1995 among respondents to the 1993 survey.

Independent Variables

The independent variables were depressive symptoms and satisfaction with health care. The 1993 survey included the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey, a health status measure constructed for use in the Medical Outcomes Study (10). The 1995 survey included the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (11), a modified version of the 36-item version. In keeping with recommendations based on receiver-operating curve analysis, a score below 43 on the mental component summary was used as a threshold to denote clinically significant depressive symptoms (12).

The 1993 survey (7) contained questions addressing 13 separate domains of health care satisfaction—six domains pertaining to the provision of clinical care and seven related to plan administration (13). Using a method outlined previously (14), we converted each scale into a dichotomous measure that compared the individuals who reported dissatisfaction to the remainder of the sample; 10%–20% of the sample reported dissatisfaction with each of the domains of care. Two summary dichotomous variables were also created, representing any clinical care domain and any administrative domain with problems.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables were two measures of workplace performance: missed work days and productivity. Respondents to the 1995 survey (8) were asked whether they had missed one or more days from work because of health problems in the previous 4 weeks. They were also asked to rate the impact of their health on effectiveness at work, on a score of zero (unable to accomplish anything because of health) to 100 (at best, with no health problems). A cutoff point of 80, which was the median score for patients with depressive illness, and the 14th percentile for the entire sample, was chosen for creating a dichotomous variable.

Statistical Methods

After comparing bivariate differences between individuals with and without depressive symptoms, we constructed a series of models to assess the association between depressive symptoms and each of the outcomes of interest (continued depressive symptoms, sick days, and reduced effectiveness at work). In order to control for potential confounding, logistic regression models adjusted for the following covariates: age, gender, race, family income, education, number of chronic conditions, plan type, and number of years enrolled in the plan.

Next, a set of analyses was used to examine the association between satisfaction with health care and the three outcomes of interest among patients with depressive symptoms. A separate logistic regression equation was constructed to model each outcome as a function of each domain of satisfaction among the subset of patients with depressive symptoms in 1993, with adjustment for the same covariates used in the first set of models.

Results

Characteristics of Respondents With and Without Depressive Symptoms at Baseline

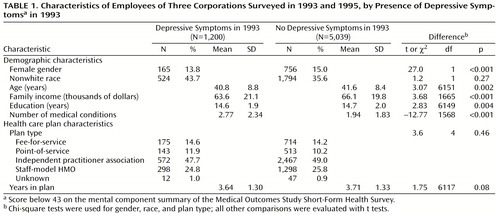

Altogether, 1,200 enrollees in the longitudinal sample (19.2%) met the criteria for depressive symptoms in 1993 (mental component summary score less than 43) (Table 1). As compared to the remainder of the sample, those with depressive symptoms were younger, were more likely to be female, had lower incomes, had less education, and had more medical conditions. There were not significant plan-level differences between the groups.

Depressive Symptoms and Work Outcomes

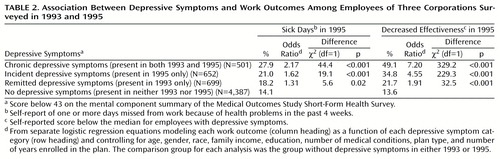

Multivariate models indicated that the odds of taking sick days at work in 1995 were 2.17 times as high for respondents with chronic depressive illness as for respondents without depressive symptoms in either 1993 or 1995, and the odds of reporting decreased effectiveness in the workplace in 1995 were 7.20 times as high. Incident depressive symptoms (present in 1995 but not 1993) were associated with an intermediate impact on workplace function in 1995. Respondents whose symptoms in 1993 had resolved by 1995 showed some persistent difficulties in workplace function, but those effects were substantially smaller than those for the groups with chronic and incident depressive symptoms (Table 2).

Relation of Satisfaction With Health Care to Outcomes Among Individuals With Depressive Symptoms

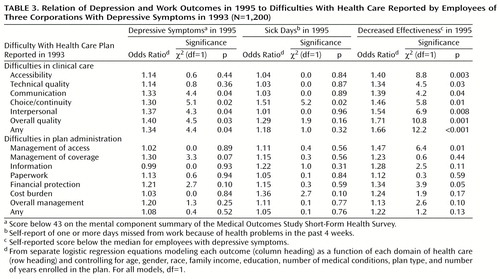

Within the subsample of individuals with depressive symptoms in 1993, a report of problems with one or more domains of clinical care in 1993 was associated with a 34% increase in the odds of continued depressive symptoms and a 66% greater adjusted odds of decreased effectiveness at work in 1995, after control for demographic and plan-level confounders (Table 3). There was a significant relationship between four of the six domains of clinical care and persistent depressive symptoms and between all six domains of clinical care and decreased effectiveness at work 2 years later. There was a less consistent association between problems with plan administration and outcomes, and there was also not a significant association between depression and sick days at follow-up.

Discussion

The study’s findings suggest that depression has a substantial and persistent association with decreased workplace productivity, an impact that may be underestimated when one looks only at days missed from work. Furthermore, consumer-reported problems in clinical care were a strong predictor both of persistent depressive symptoms and of difficulties in on-the-job function among individuals with depressive symptoms.

The impact of depression on function at work was substantially higher than its association with missed days at work. These findings suggest that previous reports of absenteeism may represent only a small fraction of the cost of depression in the workplace. “Presenteeism”—when an employee goes to work sick but cannot work at full capacity—has increasingly become a concern to employers in recent years (15). Presenteeism would be expected to be particularly likely when an employee is reluctant to report an illness or believes the illness would not be regarded as a legitimate reason for missing work. The perceived stigma associated with depressive disorders may thus result in a high proportion of hidden costs to employers that are not readily evident from health or disability claims data.

The findings from the depressed respondents in this study suggest a potential causal link between problems in health care and worse 2-year outcomes among depressed individuals. This pattern was almost exclusively seen for clinical aspects of care (as opposed to plan administration), suggesting the importance of choice, accessibility, and continuity of the patient-doctor relationship in achieving positive outcomes. It lends further support to recent findings (16) that improving clinical care can have a beneficial impact on both health and work functioning.

The survey design imposed at least two limitations. First, the work variables were obtained through self-report. However, studies using administrative data have confirmed the contribution of depressive illness to absenteeism (17), as well as the validity of depressed workers’ reports of diminished work productivity (D. Lerner, unpublished study, 2000). Second, the follow-up survey included only individuals still employed in 1995. If a subgroup of seriously depressed employees had lost their jobs by 1995, then the study’s results would be expected to underestimate the association between depressive symptoms and work outcomes.

Whatever the mechanisms linking depression, health care difficulties, and impaired work function, the study speaks to the potential importance of measuring and addressing these domains in conjunction. For employers, many of the financial costs of depression derive from its impact on workplace productivity; correspondingly, much of the value in treating depression may lie in the potential to improve work outcomes.

|

|

|

Received Aug. 14, 2000; revision received Nov. 1, 2000; accepted Nov. 27, 2000. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Druss, Departments of Psychiatry and Public Health, Yale University, Department of Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System, 116A, 950 Campbell Ave., West Haven, CT 06516; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Vistnes JP, Monheit AC: Health Insurance Status of the US Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population: MEPS Research Findings Number 1: AHCPR Publication 97-0030. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1997Google Scholar

2. Gabel JR: Job-based health insurance, 1977–98: the accidental system under scrutiny. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999; 18:62–74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Fein R: Medical Care, Medical Costs: The Search for a Health Insurance Policy. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1989Google Scholar

4. Long SH, Marquis MS: Stability and variation in employment-based health insurance coverage, 1993–7. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999; 18:133–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Davis K, Collins KS, Schoen C, Morris C: Choice matters: enrollees’ views of their health plans. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995; 14:991–995Google Scholar

6. Bodenheimer T, Sullivan K: How large employers are shaping the health care marketplace; second of two parts. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:1084–1087Google Scholar

7. Allen HM, Darling H, McNeill DN, Bastien F: The Employee Health Care Value Survey: round one. Health Aff (Millwood) 1994; 13:25–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Allen HM, Rogers WH: The consumer health plan value survey: round two. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997; 16:156–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Dillman D: Mail and Telephone Surveys: The Total Design Method. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1978Google Scholar

10. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30:473–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34:220–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1994Google Scholar

13. Allen HM: Technical Appendix, Employee Health Care Value Survey. Boston, New England Medical Center, 1994Google Scholar

14. Druss B, Schlesinger M, Thomas T, Allen H: Depressive symptoms and plan switching under managed care. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:697–701Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Hilpern K: British workers take leave of their holidays. The Independent, June 25, 2000, p 8Google Scholar

16. Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unutzer J, Miranda J, Carney MF, Rubenstein LV: Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000; 283:212–220Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Sledge WH: Health and disability costs of depressive illness in a major US corporation. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1274–1278Google Scholar