A Controlled Clinical Trial of Bupropion for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Despite the increasing recognition of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults, there is a paucity of controlled pharmacological trials demonstrating the effectiveness of compounds used in treatment, particularly nonstimulants. The authors report results from a controlled investigation to determine the anti-ADHD efficacy of bupropion in adult patients with DSM-IV ADHD. METHOD: This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, parallel, 6-week trial comparing patients receiving sustained-release bupropion (up to 200 mg b.i.d.) (N=21) to patients receiving placebo (N=19). The authors used standardized structured psychiatric instruments for diagnosis of ADHD. To measure improvement, they used separate assessments of ADHD, depression, and anxiety symptoms at baseline and each weekly visit. RESULTS: Of the 40 subjects (55% male) enrolled in the study, 38 completed the study. Bupropion treatment was associated with a significant change in ADHD symptoms at the week-6 endpoint (42% reduction), which exceeded the effects of placebo (24% reduction). In analyses using a cutoff of 30% or better reduction to denote response, 76% of the subjects receiving bupropion improved, compared to 37% of the subjects receiving placebo. Similarly, in analyses using Clinical Global Impression scale scores, 52% of the subjects receiving bupropion reported being “much improved” to “very improved,” compared to 11% of the subjects receiving placebo. CONCLUSIONS: These results indicate a clinically and statistically significant effect of bupropion in improving ADHD in adults. The results suggest a therapeutic role for bupropion in the armamentarium of agents for ADHD in adults, while further validating the continuity of pharmacological responsivity of ADHD across the lifespan.

There is an increasing awareness of the presence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. Despite controversy (1), studies of clinical correlates, neuropsychology, familial aggregation, and neuroimaging have supported the validity of this disorder in adults (2). Adults with ADHD have high rates of psychopathology, substance abuse, social dysfunction, and academic and occupational underachievement (3–5). Conversely, adults with ADHD are overrepresented among those seeking treatment for substance abuse (6, 7) and depression (8). Although ADHD was initially conceptualized as a childhood disorder, follow-up studies have documented that approximately one-half of affected youth continue to have ADHD into adulthood (3, 9–11). Although epidemiological data are limited, a relatively recent study suggests that up to 4.7% of adults may meet criteria for ADHD (12).

Despite the emerging recognition of adult ADHD, there is a paucity of data on the treatment of this disorder (13). For instance, in contrast to the more than 200 controlled studies of stimulant use in children with ADHD (14–16), we are aware of only nine controlled studies of the use of stimulants in adults with ADHD (14). Although this work has demonstrated the efficacy of stimulants for the treatment of adult ADHD, the multiple daily doses, scheduled prescribing restrictions, anxiogenic properties, and liability for abuse limit their usefulness in treating subgroups of adults with ADHD (14, 17). Moreover, the co-occurrence of mood and substance use disorders in patients with ADHD supports the development of safe and effective nonstimulant alternatives.

Tricyclic antidepressants and bupropion have emerged as second-line agents for treating pediatric ADHD (16). Bupropion is a novel aminoketone antidepressant related to the phenylisopropylamines and pharmacologically distinct from available antidepressants (18, 19). Bupropion has been shown in preclinical studies to manifest antidepressant properties with indirect dopaminergic and noradrenergic agonist effects, although the clinical relevance of these findings remains unclear (19). Bupropion at doses of up to 6 mg/kg per day has been shown in controlled clinical trials in youth to be effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, albeit less robustly than stimulants (16, 20–22). Data on ADHD in adults, however, are restricted to one open trial of 19 adults treated with an average of 360 mg/day of bupropion for 6–8 weeks (23). In this 1990 study, Wender and Reimherr (23) observed that 74% of patients completing the trial manifested a positive and sustained response. Although this information was helpful, the high dropout rate (27%), the open nature of the study, and the recent availability of a sustained-release preparation of bupropion necessitate a reexamination of the role of this compound in the treatment of adults with ADHD. To this end, we conducted a placebo-controlled trial of the sustained-release preparation of bupropion in a well-characterized group of adults with ADHD. On the basis of the available pediatric and adult literature, we hypothesized that bupropion would be superior to placebo in the treatment of adults with ADHD.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were outpatient adults with ADHD who were between 20 and 59 years of age and who were recruited from advertisements and clinical referrals to a clinical psychopharmacology clinic. We excluded potential subjects if they had any clinically significant chronic medical conditions, a history of cardiac arrhythmias or seizures, mental retardation (IQ <75), organic brain disorders, clinically unstable psychiatric conditions, bipolar disorder, drug or alcohol abuse or dependence within the 6 months preceding the study, or current use of psychotropics. This study was approved by the institutional review board of our facility; all subjects completed written informed consents before inclusion in the study.

Assessment Measures

Subjects underwent a standard clinical assessment comprising a psychiatric evaluation, a structured diagnostic interview, a cognitive battery, a medical history, physical and neurological examinations, an ECG, and an SGOT test. The diagnostic interview used was the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, supplemented for childhood disorders by unmodified modules from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Epidemiologic Version (24). To obtain a full diagnosis of adult ADHD, the subject had to have 1) fully met the DSM-IV criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD by the age of 7 as well as currently (within the past month), 2) described a chronic course of ADHD symptoms from childhood to adulthood, and 3) endorsed a moderate or severe level of impairment attributed to those symptoms. The diagnostic reliability between raters and board-certified psychiatrists was excellent. A kappa of 1.0 was obtained for ADHD diagnosis, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.8–1.0.

To assess intellectual functioning, we administered subtests of the WAIS-R and the Wide-Range Achievement Test 3 (25). Socioeconomic status was measured by use of the Hollingshead Four- Factor Index of Social Status; low values indicated high socioeconomic status.

To assess change during treatment, we examined ADHD, depression, and anxiety symptoms. As in previous reports (26, 27), overall severity in each of these domains was assessed with the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale (28). The CGI includes global severity (1=“not ill” to 7=“extremely ill”) and global improvement (1=“very much improved” to 7=“very much worse”) scales. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the CGI was 0.91. In addition, the following domain-specific rating scales were used. To assess ADHD improvement, we used the ADHD Rating Scale (29–31), which has been shown to be sensitive to drug effects in pediatric (29) and adult groups (26, 27, 32, 33). This scale, updated for DSM-IV (31), assesses each of 18 individual criteria symptoms by using an identical severity grid (0=“not present,” 3=“severe”; overall minimum score=0, overall maximum score=54) that has been shown to be correlated with ADHD in adults (34, 35) and is medication-sensitive (26, 27, 32, 33). An intraclass correlation of 0.85 was obtained for the ADHD symptom checklist. For depression we used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (minimum=0, maximum=64) (36) and the Beck Depression Inventory (minimum=0, maximum=63) (37). For anxiety we used the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (minimum=0, maximum=56) (38). In addition, adverse experiences were systematically recorded at each visit. Although the ADHD symptom checklists and the CGI were administered at baseline and at each follow-up visit, the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and Beck Depression Inventory were administered only at baseline and at the end of the study.

Procedures

This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, parallel 6-week trial comparing the results obtained with sustained-release bupropion (up to 200 mg b.i.d.) to those obtained with placebo in adults with DSM-IV ADHD. Weekly supplies of bupropion or placebo were dispensed by the pharmacy in identically appearing 100-mg capsules. Subjects were instructed to take their medication on rising and again approximately 6 hours later. Compliance was monitored by means of pill counts at each physician visit. The study medication dose was begun with 100 mg in the morning and increased by 100 mg weekly in twice-a-day doses up to 200 mg twice daily (week 4), unless adverse events emerged or the subject noted optimal improvement at a lower dose. Vital signs were assessed at baseline and each week.

Statistical Analysis

On the basis of our projected group size of 20 subjects per treatment arm, a bupropion response rate of 60%, a placebo response rate of 10%, and an alpha level of 0.05, we calculated our statistical power to be 0.89. Thus, the probability of a type II error in our analysis was 0.11. Improvement in ADHD symptoms was defined as a reduction in the ADHD Rating Scale score of 30% or better. For analyses of CGI and ADHD Rating Scale scores, we used the intent-to-treat method with the last observation carried forward. To compare the proportion of subjects improving while taking bupropion versus the number improving while taking placebo, we used Fisher’s exact test. To compare ordinal data between two time points, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired data. To compare ordinal and continuous data at baseline or endpoint, we used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. To compare study groups on binary outcomes, we used Fisher’s exact test. For continuous variables, we tested for group differences using linear regression and generalized estimation equations that estimated the main effects of drug (bupropion versus placebo) and time (week in study), as well as any interactions among variables. The model assumed a subject-specific residual that differed between subjects but was constant over time (39, 40). All statistical analyses were performed by using Stata (Stata Corporation, College Park, Tex.). All statistical tests were two-tailed, with statistical significance at 0.05. Data are expressed as means and standard deviations unless otherwise specified.

Results

Of the 154 subjects screened, 40 (26%) subjects were enrolled in the study (30 were not interested, 27 did not return for follow-up, 17 had current substance abuse, 11 were receiving exclusionary psychotropics, 10 had no ADHD, nine had bipolar or psychotic disorder, six had medical contraindications, and four had previous exposure to bupropion). The final study group consisted of 18 women and 22 men who ranged in age from 20 to 59 years (mean=38, SD=11). Thirty-eight subjects completed the protocol; two subjects dropped out because of noncompliance (both receiving bupropion).

Demographics and Comorbidity

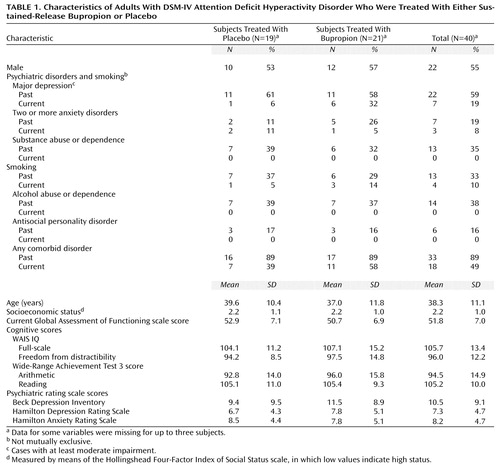

Subjects were most frequently diagnosed with the inattentive subtype of ADHD (N=23, 58%), followed by the combined (N=14, 35%) and hyperactive or impulsive subtypes (N=3, 8%). As depicted in Table 1, 89% of the subjects with ADHD had at least one past comorbid psychiatric disorder; for 49% (data were missing for three subjects), the comorbid disorder was also present within the past month. The results did not differ significantly between the placebo and bupropion groups (past ADHD: p=1.00, Fisher’s exact test; current ADHD: p=0.33, Fisher’s exact test). Before entering this study, 11 subjects had been taking medications for ADHD, seven had received counseling, and seven had received both medication and counseling. Despite this group of adults with ADHD possessing average to above-average intelligence, 17 (46%) had required tutoring in school, and 11 (30%) had repeated at least one grade (some data were missing). The rate of past smoking status did not differ between the patients in the bupropion and placebo arms (p=0.74, Fisher’s exact test). Likewise, there were also no significant differences in terms of current smoking status (p=0.61, Fisher’s exact test).

Outcome Assessment

By using categorical definitions of ADHD improvement (with last observation carried forward), bupropion was found to be clinically and statistically superior to placebo in adult patients. By using a predefined criteria of a CGI improvement rating of 1 or 2 (“much improved” to “very much improved”), a significantly higher proportion of subjects were considered improved while receiving bupropion than while receiving placebo (N=11,52%; N=2,11%) (p=0.007, Fisher’s exact test). A similar result was obtained by using a preestablished definition of improvement of 30% or more reduction in scores on the DSM-IV ADHD symptom checklist (N=16, 76%; N=7, 37%) (p=0.02, Fisher’s exact test). The same pattern of results was observed when the group was stratified by past and current smoking status, although statistical significance was not reached because of reduced group size.

Although the subjects with ADHD who were randomly selected for the active treatment arm had a baseline mean score of 32.9 (SD=7.8, range=21–47) on the ADHD symptom checklist, week-6 endpoint analysis (with last observation carried forward) revealed a 42% reduction in scores (week 6: mean=19.2, SD=11.0, range=0–41). Comparatively, placebo group baseline scores (mean=31.3, SD=8.5, range=19–47) decreased by only 24% by week 6 (mean=23.8, SD=11.8, range=7–46), resulting in a significant difference between groups (t=–2.02, df=39, p=0.05, linear regression). Results from the generalized estimation equations model, using ADHD symptom checklist scores from all time points, indicated a significant effect of time (z=–4.66, p<0.001), no significant main effect of drug (bupropion or placebo) (z=0.69, p=0.49), and no drug-by-time interaction for ADHD symptoms (z=–1.29, p=0.20). The bulk of improvement in ADHD symptom profiles occurred in weeks 5 and 6.

We also evaluated the impact of treatment on the 18 DSM-IV specific symptoms of ADHD (with last observation carried forward). These analyses showed that compared to baseline, a significantly greater number of ADHD symptoms improved in subjects receiving bupropion compared to those receiving placebo: all 18 symptoms improved significantly in the bupropion-treated group, whereas only eight (44%) of 18 of the symptoms improved in the placebo group (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test). Response to treatment was not significantly related to DSM-IV ADHD subtype (inattentive versus combined).

Baseline ratings of depression (mean Hamilton depression scale score and mean Beck Depression Inventory score) and anxiety (mean Hamilton anxiety scale score) were relatively low and did not differ between groups (all p>0.05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). When using standard cutoff points for depression (Hamilton depression scale score: >16, Beck Depression Inventory score: >19, and CGI severity scale score: 4) and anxiety (Hamilton anxiety scale score: >21 and CGI severity scale score: 4), eight subjects had scores indicative of depression at baseline per the CGI severity scale (three taking placebo and five taking bupropion), five had scores above the Beck Depression Inventory cutoff (two taking placebo and three taking bupropion), and eight had scores indicative of anxiety per the CGI severity scale (three taking placebo and five taking bupropion). There was no significant medication effect (medication versus placebo at endpoint) on the Hamilton depression scale, Beck Depression Inventory, or Hamilton anxiety scale, including analyses of all subjects stratified by the presence of abnormal baseline scores (all p>0.05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). There was no difference in ADHD symptom checklist scores or CGI ADHD scores (improvement or severity) in adults with past or current anxiety or major depression (placebo or bupropion group, p>0.05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Similarly, there was no effect of gender or socioeconomic status on response to bupropion, although we lacked adequate statistical power to fully evaluate the impact of treatment on comorbidity, socioeconomic status, or gender.

There was no relationship between response and bupropion daily dose (t=–0.11, df=19, p=0.91). Average daily doses of placebo and bupropion at the end of the trial (week 6) were 379 mg/day and 362 mg/day, respectively. At the conclusion of the study, 16 bupropion subjects (76%) were receiving the full dose of 400 mg/day, two (10%) were receiving 300 mg/day, and three (14%) were receiving 200 mg/day. A total of 57% (12 out of 21) of the bupropion responders opted to continue with bupropion treatment at the conclusion of the study.

Adverse Effects

No serious adverse drug effects were observed during the trial. Adverse effects reported in at least two (5%) of the subjects included headache (bupropion: 19%; placebo: 16%), gastrointestinal problems (19% versus 16%), insomnia (38% versus 16%), aches or pains (10% versus 5%), dry mouth (10% versus 0%), and chest pain (10% versus 0%). There were no statistically significant differences between the study groups in the rates of any single adverse event or in the rate of at least one adverse event (bupropion: N=14, 67%; placebo: N=11, 58%) (all p>0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Not including the two bupropion dropouts, five subjects taking bupropion and three subjects taking placebo lowered their dose because of adverse effects.

Evaluation of vital signs failed to reveal any differences between the subjects in the bupropion and placebo arms. Specifically, there were no statistically significant effects of bupropion compared to placebo on heart rate at week 6 (mean=78.4, SD=14.4; mean=72.7, SD=12.0, respectively) (z=–1.35, p=0.18, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Likewise, there were no significant differences between the treatment groups at endpoint on systolic (mean=127.9, SD=13.2; mean=124.6, SD=18.2) (z=–0.83, p=0.41, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) or diastolic (mean=73.5, SD=10.2; mean=73.1, SD=9.0 (z=–0.15, p=0.88, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) blood pressure.

Discussion

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, our results demonstrated the clinical efficacy and tolerability of sustained-release bupropion for the treatment of ADHD in adults. By clinical impression, 52% of adults with ADHD who received bupropion were considered “much improved” to “very much improved,” whereas only 11% of those receiving placebo were so classified (p=0.007, Fisher’s exact test). This modest therapeutic effect was seen after several weeks, which suggests an apparent delayed onset of action in these adults with ADHD.

The current results confirm and extend previous open findings in adults (23) and adolescents (41), as well as controlled studies in juveniles (20–22), that found bupropion to be effective in reducing ADHD symptom profiles. Our response rate (30% or more reduction in ADHD symptom checklist score) is identical to that reported in an open study by Wender and Reimherr (23) using the immediate-release preparation of bupropion. Moreover, the magnitude of response observed in the current study is similar to that found in previous controlled investigations in children and adolescents with ADHD employing similar weight-corrected doses of bupropion (20–22). Hence, as in results found in children and adolescents, our data indicate that adults with ADHD respond favorably to bupropion treatment.

The relatively low placebo response noted in the current study is consistent with data from our previous studies documenting the low placebo response in adult ADHD (26, 27, 32, 42). The 52% response rate (per the CGI scale) observed with bupropion in this study was somewhat lower than the response rate observed in our prior, methodologically similar trials of methylphenidate (87%) (26), desipramine (89%) (27), and amphetamine compounds (75%) (43). However, the response rate to bupropion was similar to that achieved with pemoline (50%) (42), an experimental cognition-enhancing agent (40%) (33), and the nonstimulant investigational agent tomoxetine (52%) (32). Hence, given the current results, bupropion appears to follow stimulants and desipramine in terms of efficacy for treating ADHD in adults. It remains unknown whether a longer study at higher doses could lead to better results. The study was only 6 weeks long; that may have been insufficient time for the full clinical benefit of bupropion to unfold. In support of this notion, our data suggest that the therapeutic value of bupropion was most striking in the final 2 weeks of the study, after the subjects had achieved their highest dose of bupropion. Our current data mirror previous data with desipramine in adults with ADHD, which indicated a delayed onset of maximal efficacy, with the largest improvement occurring after the dose was maximally titrated (i.e., between the 2-week end of titration and 6-week endpoint) (27).

This study was not a dose-response evaluation; our results did not identify statistically significant associations between clinical effect and bupropion dose, which is consistent with findings in pediatric studies of bupropion and other antidepressants (16). Consistent with our previous controlled studies in adults with ADHD, response to bupropion was not affected by gender or social class. Moreover, our lack of a significant association of past or current depression or anxiety influencing ADHD symptoms suggests that bupropion is effective in the presence of anxiety or depression in reducing the symptoms of ADHD.

As part of its mechanism of action, bupropion has been shown to potentiate dopaminergic neurotransmission (19). The current findings support the notion that pharmacological agents that are effective in reducing ADHD symptoms have similar catecholaminergic properties (16, 44). Agents such as stimulants and antidepressants appear to facilitate directly norepinephrine and dopamine neurotransmission, whereas nicotinic cognitive enhancers may indirectly affect such systems (33, 45, 46). For example, research suggests that recently described polymorphisms in the postsynaptic D4 receptor in youth (47) and adults (48) with ADHD may result in a blunted response to dopamine (49). If substantiated, these findings would further the hypotheses linking ADHD with catecholaminergic dysregulation in general and dopaminergic systems in particular (44).

The results of this study should be viewed in light of its methodological limitations. Only 26% of the subjects screened were enrolled in the study. The majority of subjects were from relatively high socioeconomic strata; hence, the results of the current study may not generalize to lower socioeconomic strata. Despite subjects meeting criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of depression or anxiety per structured psychiatric interview, the majority had low current scores on depression and anxiety rating scales, which limited our ability to evaluate the efficacy of bupropion in these comorbid conditions. Other limitations included the use of a relatively short exposure to a full dose of medication, which may not have allowed adequate time for the full therapeutic benefit of bupropion treatment to emerge.

Although our results are based on self-reports from affected individuals, it has been suggested that subjects with ADHD may not be ideal reporters of their disorder (29). Although this places some limits on the interpretation of our results, the significant effects on ADHD symptoms observed in this and previous studies (26, 27, 32, 33, 42, 50) suggest that adults with ADHD are acceptable reporters of their own condition. In addition, self-reports of ADHD symptoms have been shown to be a reliable and valid method of assessing ADHD in adults (51, 52).

Despite these limitations, the results of this study show that bupropion significantly improved ADHD symptoms in adults. Bupropion may have a delayed onset of action of from 4 to 6 weeks in treating ADHD. Given that it has less efficacy for ADHD compared to stimulants (26, 43), bupropion appears to be useful as a second-line agent for the treatment of uncomplicated ADHD in adults. However, because of its freedom from the liability of abuse, bupropion may be considered a first-line therapy in special groups of individuals with ADHD, such as those with substance abuse (53) or co-occurring prominent mood lability (54). Since some stimulants (methylphenidate, pemoline, and amphetamine compounds) and some antidepressants (desipramine and bupropion) have now been shown in controlled trials to be effective in treating both pediatric and adult forms of ADHD, the present results further support the validity of ADHD in adults and the continuity of treatment responsivity across the lifespan.

|

Presented in part at the 39th annual meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit, Boca Raton, Fla., June 1–4, 1999, the 152nd annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C., May 15–20, 1999, and the 46th annual meeting of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, Chicago, Oct. 20–24, 1999. Received Sept. 1, 1999; revision received March 16, 2000; accepted April 14, 2000. From the Pediatric Psychopharmacology Clinic, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School. Address reprint requests to Dr. Wilens, Pediatric Psychopharmacology Clinic, ACC 725, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston MA 02114; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from Glaxo Wellcome Incorporated, the NIH (MH-011175), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-11315) (Dr. Wilens). The authors thank John Vetrano, Harold Demonaco, and the pharmacy staff at Massachusetts General Hospital for their help.

1. Shaffer D: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:634–639Google Scholar

2. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens TE, Faraone S: Adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controversial diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 7):59–68Google Scholar

3. Weiss G, Hechtman L, Milroy T, Perlman T: Psychiatric status of hyperactives as adults: a controlled prospective 15-year follow-up of 63 hyperactive children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1985; 24:211–220Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens T, Norman D, Lapey KA, Mick E, Lehman BK, Doyle A: Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity, cognition, and psychosocial functioning in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1792–1798Google Scholar

5. Shekim WO, Asarnow RF, Hess E, Zaucha K, Wheeler N: A clinical and demographic profile of a sample of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, residual state. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:416–425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Levin FR, Kleber HD: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse: relationships and implications for treatment. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1995; 2:246–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Wilens T, Spencer T, Biederman J: Are attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the psychoactive substance use disorders really related? Harv Rev Psychiatry 1995; 3:260–262Google Scholar

8. Alpert J, Maddocks A, Nierenberg A, O’Sullivan R, Pava J, Worthington J, Biederman J, Rosenbaum J, Fava M: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in childhood among adults with major depression. Psychiatry Res 1996; 62:213–219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:565–576Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, Curtis S, Chen L, Marrs A, Ouellette C, Moore P, Spencer T: Predictors of persistence and remission of ADHD into adolescence: results from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:343–351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Fischer M: Persistence of ADHD into adulthood: it depends on whom you ask. ADHD Report 1997; 5:8–10Google Scholar

12. Murphy K, Barkley RA: Prevalence of DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD in adult licensed drivers: implications for clinical diagnosis. J Attention Disorders 1996; 1:147–161Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ: Pharmacotherapy of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. CNS Drugs 1998; 9:347–356Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Wilens TE, Spencer TJ: The stimulants revisited. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2000; 9:573–603Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Swanson J, McBurnett K, Christian D, Wigal T: Stimulant medications and the treatment of children with ADHD. Advances in Clin Child Psychol 1995; 17:265–322Google Scholar

16. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, Harding M, O’Donnell D, Griffin S: Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit disorder across the life cycle. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:409–432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Turnquist K, Frances R, Rosenfeld W, Mobarak A: Pemoline in attention deficit disorder and alcoholism: a case study. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:622–624Link, Google Scholar

18. Baldessarini RJ: Chemotherapy in Psychiatry. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

19. Ascher JA, Cole JO, Colin J, Feighner JP, Ferris RM, Fibiger HC, Golden RN, Martin P, Potter WZ, Richelson E, Sulser F: Bupropion: a review of its mechanism of antidepressant activity. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:395–401Medline, Google Scholar

20. Casat CD, Pleasants DZ, Fleet JVW: A double-blind trial of bupropion in children with attention deficit disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23:120–122Medline, Google Scholar

21. Conners CK, Casat CD, Gualtieri CT, Weller E, Reader M, Reiss A, Weller RA, Khayrallah M, Ascher J: Bupropion hydrochloride in attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:1314–1321Google Scholar

22. Barrickman L, Perry P, Allen A, Kuperman S, Arndt S, Herrmann K, Schumacher E: Bupropion versus methylphenidate in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:649–657Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Wender PH, Reimherr FW: Bupropion treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1018–1020Google Scholar

24. Orvaschel H: Psychiatric interviews suitable for use in research with children and adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull 1985; 21:737–745Medline, Google Scholar

25. Wechsler D: Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corporation, 1981Google Scholar

26. Spencer T, Wilens T, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Ablon JS, Lapey K: A double-blind, crossover comparison of methylphenidate and placebo in adults with childhood-onset attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:434–443Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV, Warburton R, Schleifer D, Harding M, Linehan C, Geller D: Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1147–1153Google Scholar

28. National Institute of Mental Health: CGI (Clinical Global Impression) scale. Psychopharmacol Bull 1985; 21:839–843Google Scholar

29. Barkley RA: Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, Guilford Press, 1990Google Scholar

30. DuPaul G: The ADHD Rating Scale: Normative Data, Reliability, and Validity. Worcester, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 1990Google Scholar

31. DuPaul G, Power T, Anastopoulos A, Reid R: ADHD Rating Scale IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. New York, Guilford, 1998Google Scholar

32. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, Prince J, Hatch M, Jones J, Harding M, Faraone SV, Seidman L: Effectiveness and tolerability of tomoxetine in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:693–695Link, Google Scholar

33. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Bostic J, Prince J, Monuteaux MC, Soriano J, Fine C, Abrams A, Rater M, Polisner D: A pilot controlled clinical trial of ABT-418, a cholinergic agonist, in the treatment of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1931–1937Google Scholar

34. Barkley RA, Biederman J: Towards a broader definition of the age-of-onset criterion for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1204–1210Google Scholar

35. Murphy K, Barkley RA: Preliminary normative data on DSM-IV criteria for adults. ADHD Report 1995; 3(3):6–7Google Scholar

36. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Gibbons RD, Hedeker D, Elkin I, Waternaux C, Kraemer HC, Greenhouse JB, Shea T, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Watkins JT: Some conceptual and statistical issues in analysis of longitudinal psychiatric data. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:739–750Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Bailor JC, Mosteller F: Medical Uses of Statistics. Waltham, Mass, New England Journal of Medicine Books, 1986Google Scholar

41. Riggs PD, Leon SL, Mikulich SK, Pottle LC: An open trial of bupropion for ADHD in adolescents with substance use disorders and conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:1271–1278Google Scholar

42. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Frazier J, Prince J, Bostic J, Rater M, Soriano J, Hatch M, Sienna M, Millstein RB, Abrantes A: Controlled trial of high doses of pemoline for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19:257–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Spencer TJ, Wilens TE, Biederman J, Kagan JB, Bearman SK: Effectiveness and tolerability of Adderall for adults with ADHD, in 1999 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1999, p 256Google Scholar

44. Zametkin A, Liotta W: The neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:17–23Medline, Google Scholar

45. Levin E: Nicotinic systems and cognitive function. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992; 108:417–431Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Shih T, Khachaturian Z, Barry H III, Hanin I: Cholinergic mediation of the inhibitory effect of methylphenidate on neuronal activity in the recticular formation. Neuropharmacology 1976; 15:55–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. LaHoste GJ, Swanson JM, Wigal SB, Glabe C, Wigal T, King N, Kennedy JL: Dopamine D4 receptor gene polymorphism is associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry 1996; 1:121–124Medline, Google Scholar

48. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Weiffenbach B, Keith T, Chu MP, Weaver A, Spencer TJ, Wilens TE, Frazier J, Cleves M, Sakai J: The dopamine D4 gene 7-repeat allele and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:768–770Abstract, Google Scholar

49. Ashgari V, Sanyal S, Buchwaldt S, Paterson A, Jovanovic V, VanTol H: Modulation of intracellular cyclic AMP levels by different human dopamine D4 receptor variants. J Neurochem 1995; 65:912–915Medline, Google Scholar

50. Findling RL, Schwartz MA, Flannery DJ, Manos MJ: Venlafaxine in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an open clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 57:184–189Google Scholar

51. Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW: The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:885–890Link, Google Scholar

52. Stein MA, Sandoval R, Szumowski E, Roizen N, Reinecke MA, Blondis TA, Klein Z: Psychometric characteristics of the Wender Utah Rating Scale: reliability and factor structure for men and women. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:425–431Medline, Google Scholar

53. Riggs PD: Clinical approach to treatment of ADHD in adolescents with substance use disorders and conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:331–332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Stoll AL, Mayer PV, Kolbrener M, Goldstein E, Suplit B, Lucier J, Cohen BM, Tohen M: Antidepressant-associated mania: a controlled comparison with spontaneous mania. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1642–1645Google Scholar