A Study of Women Who Stalk

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined whether female stalkers differ from their male counterparts in psychopathology, motivation, behavior, and propensity for violence. METHOD: Female (N=40) and male (N=150) stalkers referred to a forensic mental health clinic were compared. RESULTS: In this cohort, female stalkers were outnumbered by male stalkers by approximately four to one. The demographic characteristics of the groups did not differ, although more male stalkers reported a history of criminal offenses. Higher rates of substance abuse were also noted among the male stalkers, but the psychiatric status of the groups did not otherwise differ. The duration of stalking and the frequency of associated violence were equivalent between groups. The nature of the prior relationship with the victim differed, with female stalkers more likely to target professional contacts and less likely to harass strangers. Female stalkers were also more likely than male stalkers to pursue victims of the same gender. The majority of female stalkers were motivated by the desire to establish intimacy with their victim, whereas men showed a broader range of motivations. CONCLUSIONS: Female and male stalkers vary according to the motivation for their pursuit and their choice of victim. A female stalker typically seeks to attain a close intimacy with her victim, who usually is someone previously known and frequently is a person cast in the professional role of helper. While the contexts for stalking may differ by gender, the intrusiveness of the behaviors and potential for harm does not.

The “modal” stalker has been described as a “male in his fourth decade of life pursuing a prior sexual intimate” (1). Clinical and epidemiological studies confirm that the primary perpetrators of this crime are men and that the overwhelming majority of victims are women (2–6). Nonetheless, stalking is a gender-neutral behavior. However, outside the literature on erotomania (7–10), little attention has been given to women who persistently intrude on and stalk others.

Stalking by women is not uncommon. Community-based studies of stalking victimization indicate that women are identified as perpetrators in 12%–13% of cases (4, 11). Studies conducted in forensic mental health settings have reported higher rates, often reflecting the greater incidence of erotomania in these populations. Zona et al. (12) reported that 32% of subjects (N=24 of 74) investigated by a specialist antistalking unit were female, six of whom were classified as erotomanic. Harmon et al. (13) similarly found that 33% of stalkers (N=16 of 48) referred to a forensic psychiatry clinic were female, although this rate dropped to 22% (N=38 of 175) in a subsequent and larger study (14). Other studies have reported rates of between 17% (1) and 22% (15). In addition to first-hand victim accounts (16, 17), further illustrative examples of female harassers abound in media reports on the stalking of celebrities (e.g., actor Brad Pitt, author Germaine Greer, and television host David Letterman).

Despite the frequency with which women engage in stalking, to our knowledge no study to date has considered the contexts in which this behavior emerges among women or whether female stalkers differ from their male counterparts in relation to stalking characteristics or propensity for violence. Greater awareness of and attention to this issue is indicated for several reasons. In our experience, those who find themselves the victim of a female stalker often confront indifference and skepticism from law enforcement and other helping agencies. Not infrequently, male victims allege that their complaints have been trivialized or dismissed, some victims being told that they should be “flattered” by all the attention. In the case of same-gender stalking by women, the sexual orientation of both the victim and the perpetrator is frequently questioned, with authorities often inappropriately assuming a homosexual motive (18). Victimization studies indicate that women are seldom prosecuted for stalking offenses, with criminal justice intervention most likely to proceed in those cases involving a male suspect accused of stalking a woman (3). The available evidence suggests that stalking by women has yet to be afforded the degree of seriousness attached to harassment perpetrated by men. This is despite any empirical evidence that women are any less intrusive or persistent in their stalking or pose any less of a threat (physical or otherwise) to their victims.

This study describes a group of female stalkers and compares them to a male stalker group to examine any differences in demographic characteristics; psychiatric status; motivation, methods, or duration of stalking; or rates of associated threats and assault.

Method

The case material was drawn from referrals over an 8-year period (1993–2000) to a community forensic mental health clinic that specializes in the assessment and management of both stalkers and stalking victims. The cases were assessed by one or more of the authors. Referrals came from throughout the Australian state of Victoria (population: 4.7 million), predominantly through courts, community correctional services, police, and medical practitioners. Collaborative information was available usually in the form of victim statements, police summaries of the offenses, official criminal records, and psychological or psychiatric reports. For the purposes of this study, we defined stalking as persistent (duration of at least 4 weeks) and repeated (10 or more) attempts to intrude on or communicate with a victim who perceived the behavior as unwelcome and fear-provoking (5). This was an intentionally conservative definition to ensure that members of the study group were unequivocally stalkers. The psychiatric classification employed DSM-IV criteria.

A subgroup of female stalkers was identified and compared to their male counterparts in relation to demographic and stalking characteristics. The data analyses were conducted by using SPSS version 9.01 (SPSS, Chicago). Discrete variables were compared by using chi-square analyses, and continuous variables were compared by using Mann-Whitney U tests (two-tailed). The error rate required to demonstrate significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Demographic Profile

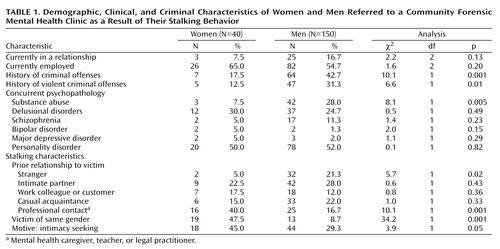

Of 190 stalkers referred to the clinic during the study period, 40 (21%) were female. The median age of the women was 35 years (range=15–60). As seen in Table 1, only three women were in stable intimate relationships when they commenced their stalking activities; most were single (60%, N=24), with 33% (N=13) separated or divorced. Most were employed, although 35% were unemployed. Female and male stalkers did not differ in terms of age (mean=36.5 [SD=9.7] and 37.6 [SD=11.1] years, respectively; t=0.56, df=188, p<0.57) or marital or employment status. However, female stalkers were significantly less likely than male stalkers to have a history of either criminal offenses or violent criminal offenses (Table 1).

Psychiatric Status

Axis I diagnoses were found in 18 female stalkers. Twelve manifested delusional disorders (erotomanic type [N=8] and jealous type [N=2], with two morbid infatuations categorized as delusional disorder, unspecified type). The other axis I diagnoses were schizophrenia (one of whom exhibited erotomanic delusions), bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Personality disorders were diagnosed in an additional 20 of the female stalkers (predominantly dependent [N=6], borderline [N=6], and narcissistic types [N=3]). No diagnosis was assigned in two cases. The rate of substance abuse was lower in female than in male stalkers (Table 1). Otherwise, the diagnostic profile (presence of delusional disorders, personality disorders, morbid infatuations/jealousy, paraphilias, schizophrenia, or other axis I disorders) of female stalkers did not differ significantly from that of the male stalkers (χ2=10.6, df=5, p=0.06).

Prior Relationship to Victim

In 95% of the cases, female stalkers pursued someone previously known to them. Sixteen (40%) of the victims were professional contacts, who in most cases were mental health professionals, although several pursued teachers or legal practitioners. In about 23% of the cases (N=9), the victim was a former intimate partner (seven were male, two were female). About 18% (N=7) were victims encountered through other work-related contexts (e.g., colleagues or customers), and 15% (N=6) were casual acquaintances. Only two women stalked strangers. The nature of the prior relationship differed significantly from that of male stalkers (χ2=11.9, df=4, p=0.02), with female stalkers being significantly more likely to target professional contacts and significantly less likely to pursue strangers (Table 1).

The rate of same-gender stalking was significantly higher among female stalkers, with 48% (N=19) pursuing other women, whereas 9% (N=13) of the men stalked other men (Table 1).

Stalking Motivation and Duration

Mullen et al. (5) proposed five categories of stalking that were based on the motivation for the pursuit and the context in which it emerged. In this cohort, 45% (N=18) of the female stalkers were classified as intimacy seekers, the stalking arising from a desire to establish a close and loving intimacy with the victim, who in most instances (78%, N=14 of 18) was a professional contact. Ten women (25%) were deemed “rejected” stalkers, who responded to the termination of a close relationship by pursuing the victim. In most cases of rejected stalking, the harassment followed the breakdown of a sexually intimate relationship, although one woman commenced stalking her psychiatrist after the abrupt cessation of long-term psychotherapy. In 18% (N=7) of the cases, the stalking was classified as “resentful,” the stalker seeking to punish and torment a victim perceived as having mistreated or slighted her. This type of stalking often emerged in the context of workplace disputes, one woman commencing a campaign of intimidation against a colleague after complaints of professional misconduct were lodged against her. Four cases (10%) were regarded as incompetent suitors, the stalking serving as a crude and intrusive means of establishing a date. There were no instances among female subjects of sexually motivated predatory stalking, whereas 7% (N=11) of the male subjects demonstrated this stalking pattern. Significantly more female stalkers were motivated by the desire to establish a loving intimacy with the object of their unwanted attention (Table 1), but they did not differ from their male counterparts in the frequency of rejected, resentful, or incompetent types of stalking.

The duration of stalking ranged between 2 months and 20 years (median=22 months), which did not differ significantly from that of male stalkers (median=12 months, range=1–240) (Mann-Whitney U=2545.00, p=0.14).

Stalking Behaviors and Associated Violence

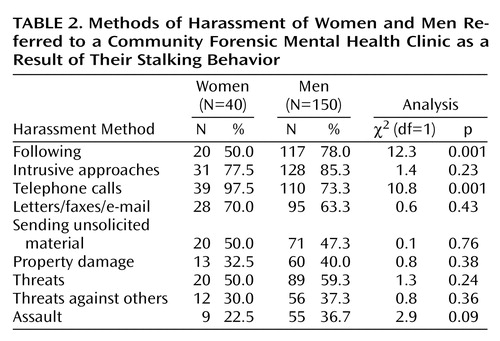

Methods of harassment are shown in Table 2. Female stalkers were significantly less likely than male stalkers to follow their victims but significantly more likely to favor telephone calls. The number of harassment methods employed by female stalkers (median=4, range=1–7) did not significantly differ from that of male stalkers (median=4, range=1–7) (Mann-Whitney U=2695.00, p=0.44). Female stalkers also showed the same propensity for threats and violence as their male counterparts, although the rates of physical assault were somewhat higher among male stalkers (Table 2). Thirteen female stalkers inflicted property damage against their victims (seven who were male, six who were female), including one woman who caused extensive damage to her ex-fiancé’s sports car and another who painted obscene messages on the fence of her victim’s home. Nine female stalkers assaulted their victims (three who were male, six who were female). The nature of the assaults did not differ qualitatively from that of male perpetrators, although no sexual assaults were committed by female stalkers. While the rates of threats and assaults did not differ significantly, female stalkers were less likely than their male counterparts to proceed from explicit threats to actual physical assaults (30% versus 49%, respectively; χ2=16.1, df=1, p=0.001).

Discussion

This study compared the demographic and pursuit characteristics of women and men referred to a community forensic mental health clinic as a result of their stalking behavior. Female stalkers did not differ from their male counterparts in terms of their demographic profiles or psychiatric status, although male stalkers were more likely to have histories of criminality and substance abuse. The intrusiveness and duration of stalking activities were equivalent between groups, as were the rates of associated threats and violence. What did distinguish female from male stalkers, however, was their choice of victim, the underlying motivation for their stalking, and the context in which their behavior emerged.

With only two exceptions, female stalkers in this study pursued an individual already known to them. A substantial proportion (40%) fixed their attention on those with whom they had professional contact, particularly psychiatrists, psychologists, and family physicians, although teachers and legal professionals were occasionally targeted. While the choice of victim among female stalkers was heavily skewed toward professional contacts, male stalkers pursued a broader range of victims, with similar proportions harassing prior intimate partners, acquaintances, strangers, and professionals. Stalking by men was also more strongly gendered, with 91% pursuing victims of the opposite sex, in contrast to women, who were equally likely to target men and women. Very few cases of same-gender stalking among women, however, involved homosexual motivations. Only two women in this series reported their sexual orientation as being homosexual; in both instances, their stalking was directed against prior sexual intimates. While it is often assumed that same-gender stalking cases involve homosexuality in either the perpetrator, the victim, or both, the data here suggest that this is the exception rather than the rule (see also reference 18).

Closely related to the choice of victims among female stalkers was the motivation for the stalking. For almost one-half, the stalking emerged from a desire to forge an intimate relationship with the victim. One-quarter of the female stalkers manifested erotomanic delusions, with the remainder hopeful that their pursuit would culminate in a relationship. The nature of the hoped-for intimacy, although usually romantic or sexual, also encompassed such aspirations as establishing a friendship or even a mothering alliance with the victim. Given the rates of serious mental illness among female stalkers in this sample (18 of 40 [45%] had major axis I psychiatric diagnoses), it is perhaps not surprising that mental health clinicians were so frequently targeted, their professional concern and empathy easily reconstructed as romantic interest.

While research has examined the risks of violence posed by patients against clinicians (19–21), few studies have considered the risks of stalking by current or former clients. Romans et al. (22) reported that 6% (N=10 of 178) of the university counselors in their survey indicated having been stalked by a client, including five female perpetrators. Sandberg et al. (23) identified 17 psychiatric inpatients (three who were female), who had stalked, harassed, or threatened hospital staff after discharge. Lion and Herschler (24) described nine case studies involving clinicians who were stalked by clients, including seven psychiatrists, a psychologist, and one plastic surgeon who was fatally attacked by a female patient. Although small and selective, these studies point to the stalking of clinicians as a salient and potentially damaging behavior. In our experience, mental health practitioners who have been stalked by patients not infrequently confront judgmental rather than sympathetic responses from their colleagues, with accusations of incompetence in managing transference issues common in such cases. A handful of clinicians have ultimately abandoned their careers because of the experience of being stalked coupled with a lack of support from their peers. Greater recognition of the vulnerability of health professionals to stalking is warranted. At a minimum, clinical and administrative policies regarding inappropriate contact and harassment by clients should be developed and adhered to by workplaces, so that when such problems arise they can be acted on expeditiously and afford health professionals better protection.

Contrary to popular assumptions, this study found that female stalkers are no less likely than their male counterparts to threaten their victims or attack their person or property. Male stalkers were more likely, however, to progress from explicit threats to physical assaults on the victim. The methods of harassment were largely equivalent between the groups, the exceptions being telephone calls (favored by all but one female stalker) and following (preferred by male stalkers). The tenacity male and female stalkers apply to their quest is also strikingly similar. Thus, while the contexts for stalking vary between men and women, the intrusiveness of the conduct and its potential for harm does not. There is no reason to presume that the impact of being stalked by a female would be any less devastating than that of a man, although insufficient data precluded analysis of this issue here.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare female and male stalkers. Women undoubtedly are the predominant victims of the crime of stalking, but it is important to recognize that in a significant minority of stalking cases, women are the perpetrators. Female stalkers are typically socially isolated individuals with high rates of mental illness and characterological disturbance. Although driven in some instances by resentment or retaliation for perceived hurts, the majority are motivated by a desire to establish an intimate relationship with the victim, who often is a professional helper. Psychiatric interventions aimed at managing the underlying mental illness are crucial to the resolution of stalking behaviors in this group, but therapists providing such treatment should be cognizant of the vulnerability sometimes inherent in this role.

|

|

Received Feb. 27, 2001; revision received June 4, 2001; accepted July 13, 2001. From the Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health and the Department of Psychological Medicine, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia. Address reprint requests to Ms. Purcell, Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health, Locked Bag 10, Fairfield, Victoria, 3078, Australia; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a postgraduate award from the Federal Government of Australia to Ms. Purcell.

1. Meloy JR, Rivers LD, Siegel L, Gothard S, Naimark D, Nicolini JR: A replication study of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. J Forensic Sci 2000; 45:147-152Medline, Google Scholar

2. Pathé M, Mullen PE: The impact of stalkers on their victims. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:12-17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hall DM: The victims of stalking, in The Psychology of Stalking: Clinical and Forensic Perspectives. Edited by Meloy JR. San Diego, Academic Press, 1998, pp 113-137Google Scholar

4. Tjaden P, Thoennes N: Stalking in America: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC, National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998Google Scholar

5. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, Stuart GW: Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1244-1249Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Budd T, Mattinson J: The Extent and Nature of Stalking: Findings From the 1998 British Crime Survey. London, Home Office, Research and Development Statistics, 2000 Google Scholar

7. Enoch MD, Trethowan WH: Uncommon Psychiatric Syndromes. Bristol, UK, John Wright & Sons, 1979Google Scholar

8. Segal JH: Erotomania revisited: from Kraepelin to DSM-III-R. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:1261-1266Link, Google Scholar

9. Rudden M, Sweeney J, Frances A: Diagnosis and clinical course of erotomanic and other delusional patients. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:625-628Link, Google Scholar

10. Mullen PE, Pathé M: The pathological extensions of love. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:614-623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Purcell R, Pathé M, Mullen PE: The incidence and nature of stalking in the Australian community. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

12. Zona MA, Sharma KK, Lane J: A comparative study of erotomanic and obsessional subjects in a forensic sample. J Forensic Sci 1993; 38:894-903Medline, Google Scholar

13. Harmon RB, Rosner R, Owens H: Obsessional harassment and erotomania in a criminal court population. J Forensic Sci 1995; 40:188-196Medline, Google Scholar

14. Harmon RB, Rosner R, Owens H: Sex and violence in a forensic population of obsessional harassers. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 1998; 4:236-249Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Palarea RE, Zona MA, Lane JC, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J: The dangerous nature of intimate relationship stalking: threats, violence and associated risk factors. Behav Sci Law 1999; 17:269-283Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Orion D: I Know You Really Love Me: A Psychiatrist’s Journal of Erotomania, Stalking, and Obsessive Love. New York, Macmillan, 1997Google Scholar

17. Fine R: Being Stalked: A Memoir. London, Chatto & Windus, 1997Google Scholar

18. Pathé M, Mullen PE, Purcell R: Same-gender stalking. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2000; 28:191-197Medline, Google Scholar

19. Phillips SP, Schneider MS: Sexual harassment of female doctors by patients. N Engl J Med 1993:329:1936-1939Google Scholar

20. Brown GP, Dubin WR, Lion JR, Garry LJ: Threats against clinicians: a preliminary descriptive classification. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1996; 24:367-376Medline, Google Scholar

21. O’Sullivan M, Meagher D: Assaults on psychiatrists—a three year retrospective study. Irish J Psychol Med 1998; 15:54-57Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Romans JSC, Hays JR, White TK: Stalking and related behaviors experienced by counseling center staff members from current or former clients. Professional Psychol: Res and Practice 1996; 27:595-599Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Sandberg DA, McNiel DE, Binder RL: Characteristics of psychiatric inpatients who stalk, threaten, or harass hospital staff after discharge. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1102-1105Link, Google Scholar

24. Lion JR, Herschler JA: The stalking of clinicians by their patients, in The Psychology of Stalking: Clinical and Forensic Perspectives. Edited by Meloy JR. San Diego, Academic Press, 1998, pp 165-173Google Scholar