Muscle Dysmorphia in Male Weightlifters: A Case-Control Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Muscle dysmorphia is a form of body dysmorphic disorder in which individuals develop a pathological preoccupation with their muscularity. METHOD: The authors interviewed 24 men with muscle dysmorphia and 30 normal comparison weightlifters, recruited from gymnasiums in the Boston area, using a battery of demographic, psychiatric, and physical measures. RESULTS: The men with muscle dysmorphia differed significantly from the normal comparison weightlifters on numerous measures, including body dissatisfaction, eating attitudes, prevalence of anabolic steroid use, and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and eating disorders. The men with muscle dysmorphia frequently described shame, embarrassment, and impairment of social and occupational functioning in association with their condition. By contrast, normal weightlifters displayed little pathology. Indeed, in an a posteriori analysis, the normal weightlifters proved closely comparable to a group of male college students recruited as a normal comparison group in an earlier study. CONCLUSIONS: Muscle dysmorphia appears to be a valid diagnostic entity, possibly related to a larger group of disorders, and is associated with striking and stereotypical features. Men with muscle dysmorphia differ sharply from normal weightlifters, most of whom display little psychopathology. Further research is necessary to characterize the nosology and potential treatment of this syndrome.

A large literature has addressed disorders of body image in women (1, 2), but few studies have explored these issues in men. Two relatively recent controlled investigations examined body image problems among men with eating disorders (3, 4); both found highly significant differences between men with eating disorders and normal comparison men. Several other studies have examined men without eating disorders. In these studies, men who were dissatisfied with their bodies generally wanted to gain weight (5–10). However, these men apparently wanted to gain muscle weight as opposed to fat—a distinction not systematically addressed in many of the studies.

Studies of male athletes have demonstrated the importance of this distinction. For example, Pasman and Thompson (11) administered measures of body image and eating disturbance to male and female runners, weightlifters, and nonexercising individuals. The male weightlifters and runners scored significantly higher than the normal control men on the drive for thinness, bulimia, and body dissatisfaction scales of the Eating Disorders Inventory (12). Blouin and Goldfield (13) found that 43 male bodybuilders reported significantly greater body dissatisfaction scores on the Eating Disorders Inventory and a higher drive for bulk, drive for thinness, and bulimic tendencies than 48 male runners or 48 martial artists. The authors explained the seemingly contradictory drives for bulk and for thinness as a reflection of the bodybuilders’ desire to gain weight in lean body mass without gaining body fat.

Our group has previously described a syndrome in men that we termed “reverse anorexia nervosa” (14, 15). Men with this syndrome worried that they looked small, even though they were actually muscular. Most avoided beaches, swimming pools, locker rooms, and other places where their bodies might be seen; if such exposure was unavoidable, they experienced distress. They typically exercised compulsively, and many used anabolic-androgenic steroids (abbreviated in this report as “steroids”), thus risking adverse medical and psychiatric effects (15).

Since the publication of our initial report, we have continued to encounter both male and female athletes who have reported a chronic preoccupation with the notion that they were not sufficiently muscular. Many reported serious impairment of social and occupational functioning, marked subjective distress, and chronic use of performance-enhancing drugs in response to this preoccupation. This syndrome appears to represent a form of body dysmorphic disorder (16, 17), except that it is characterized by preoccupation with overall muscularity, as opposed to preoccupation with the imagined ugliness of a specific body part. Accordingly, in a publication (18), we proposed to change the name of this syndrome from “reverse anorexia nervosa” to “muscle dysmorphia.” That same report described qualitative features of the syndrome, offered operational criteria for its diagnosis, and provided illustrative case reports.

In this report, we present the results of a case-control comparison study of 24 men with muscle dysmorphia and 30 normal comparison weightlifters. Some qualitative features of 15 of the men with muscle dysmorphia were briefly described in our earlier article (18); the present report presents controlled quantitative data on the full sample.

Method

We placed advertisements in 23 Boston-area gymnasiums, offering $60 to interview male weightlifters “aged 18–30 who can bench press their own body weight at least 10 times but are still sometimes concerned that [they] look small.” To recruit normal comparison subjects, we placed advertisements in the same gymnasiums but at different times, seeking “weightlifters who can bench press their body weight at least 10 times and who have been lifting weights for at least 2 years.” The requirement that the subjects be able to bench press their own body weight 10 times ensured that subjects would be fairly muscular. By recruiting normal comparison subjects in the same gymnasiums with the same criteria for muscularity, we sought to obtain a representative sample of individuals without muscle dysmorphia from the same source population from which the cases arose.

We screened respondents to both advertisements by telephone, using three screening questions: 1) did the respondent spend more than 30 minutes a day preoccupied with thoughts of being too small or insufficiently muscular; 2) did this preoccupation affect his social functioning (i.e., avoiding social situations for fear of looking too small or refusing to take off his shirt in public); and 3) had he given up enjoyable activities because of this preoccupation? Simply giving up enjoyable activities to go to the gymnasium, in the absence of frank body image preoccupations, did not suffice for a diagnosis of muscle dysmorphia. Subjects endorsing all three items were invited to participate as members of the muscle dysmorphia group; those endorsing none of the items were invited to participate as normal comparison subjects; those who endorsed one or two of the three items were excluded. All subjects provided written informed consent for the study, which was approved by the McLean Hospital’s institutional review board.

Measures

Physiological measures

We first measured subjects’ height, weight, and body fat. Body fat was calculated from six skin-fold measurements by using calipers (19). We then calculated subjects’ fat-free mass index, using an equation that we have previously published (20):

where Wt is weight in kilograms, BF is body fat percent, and Ht is height in meters.

The fat-free mass index is an objective measure of an individual’s degree of muscularity. Men who do not lift weights typically display fat-free mass indexes between 18 and 21. Fat-free mass indexes for bodybuilders who do not take steroids normally fall into the low 20s (ranging from 21 to 25), whereas fat-free mass indexes for steroid users may extend into the upper 20s or even low 30s (20).

Psychological measures

We then administered 1) basic demographic questions, 2) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV—Patient Version (SCID-P) (21) to assess current and past histories of DSM-IV axis I disorders, and 3) questions regarding history of anabolic steroid use. Next, we inquired about symptoms of muscle dysmorphia, using questions from 4) the body dysmorphic disorder diagnostic module of the SCID-P (22), 5) the body dysmorphic disorder modification of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (23), and 6) a Muscle Dysmorphia Symptom Questionnaire of our own design (description to follow).

Subjects also completed 7) the Eating Disorders Inventory; 8) a brief questionnaire evaluating exercise behavior (24); 9) a questionnaire evaluating family and childhood environment, together with demographic information, derived from Finkelhor’s Life Events Questionnaire (25); and 10) a family/childhood interview, also derived largely from Finkelhor (25), assessing familial psychopathology, family relationships, sexual orientation, and childhood physical and sexual abuse.

We also questioned subjects about any psychiatric disturbances in first-degree relatives. The subjects’ responses to this question were transcribed verbatim and presented to a blinded rater (J.I.H.) who made forced-choice diagnoses of DSM-IV axis I disorders in relatives on the basis of available information. These methods have been described previously (3, 15). Reports of childhood sexual abuse were also transcribed verbatim and scored, using previously published criteria (3, 15), by the same rater, who was again blinded to the subjects’ group status.

In total, these measures required a maximum of 2 hours per subject to complete. Subjects were compensated $60 for their participation.

Statistical Analysis

We compared subjects with muscle dysmorphia and normal comparison weightlifters on all outcome measures. In addition to the analyses planned in the original study design, we performed an a posteriori analysis comparing data from the two groups of weightlifters in the present study with similar data from 25 college men with eating disorders and 25 male college students without eating disorders who were evaluated in an earlier study by means of virtually identical instruments (3).

In both the planned and a posteriori analyses, we used Fisher’s exact test for binary outcomes, the t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous outcomes, and the exact trend test for 2-by-k ordered categories. All tests were two-tailed. To control for the effects of multiple comparisons, we used Tukey’s test for the ANOVA results. It should be noted, however, that the other significance levels in this article are presented without correction for multiple comparisons. Thus, the reader should recognize that some comparisons with p values <0.05, especially those of marginal significance, may represent chance associations. We used SAS, version 6.12, for all analyses (26).

Results

Subjects

Thirty-eight men called in response to the muscle dysmorphia advertisement. We excluded 14 at telephone screening because they did not endorse all three of the muscle dysmorphia screening questions previously described. However, none of these 14 men was included in the normal comparison group, because all answered “yes” to at least one of the muscle dysmorphia screening questions. Of the 24 subjects interviewed in person, one was excluded, because further questioning revealed that he did not experience sufficient body image disturbance to qualify for muscle dysmorphia but merely exercised excessively. Thus, 23 subjects with muscle dysmorphia remained for analysis.

Thirty-nine men responded to the normal comparison advertisement. We excluded eight at telephone screening because they endorsed one or two muscle dysmorphia items. One additional man endorsed all three questions for past muscle dysmorphia on telephone screening and thus was invited for an interview and was classified into the muscle dysmorphia group. The remaining 30 men endorsed no muscle dysmorphia screening questions and were invited for interviews as normal comparison subjects. Thus, 24 men meeting the criteria for current or past muscle dysmorphia and 30 normal comparison subjects were available for analysis. Of the 24 subjects with muscle dysmorphia, only one (4%) reported exclusively a past history of muscle dysmorphia, whereas the remaining 23 (96%) reported current muscle dysmorphia.

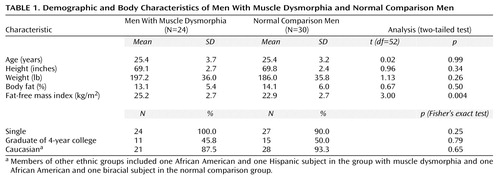

The two groups of weightlifters closely resembled each other on demographic characteristics, except that the subjects with muscle dysmorphia were significantly more muscular, as assessed by the fat-free mass index, than the normal comparison weightlifters (Table 1).

Characteristics of Muscle Dysmorphia

Among the 24 men with muscle dysmorphia, the mean age at onset of muscle dysmorphia was 19.4 years (SD=3.6). Ten (42%) were rated as showing “excellent” or “good” insight into their preoccupation in that they recognized that their perception of their own size was inaccurate. Twelve (50%) showed “fair” or “poor” insight, and two (8%) subjects lacked insight altogether, in that they were completely convinced that they were small, even when repeatedly given evidence to the contrary.

On the body dysmorphic disorder modification of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, subjects with muscle dysmorphia displayed prominent pathology. Twelve (50%) reported that they spent more than 3 hours per day thinking about their muscularity. Fourteen (58%) reported “moderate” or “severe” avoidance of activities, places, and people because of their perceived body defect. Thirteen (54%) reported “little” or “no” control over their compulsive weightlifting and dietary regimens. Two subjects reported giving up well-paying professional jobs to work at gymnasiums where they could lift weights themselves.

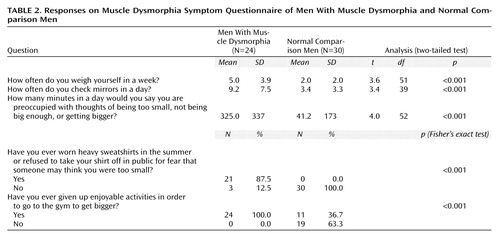

The impairment associated with muscle dysmorphia was also illustrated on the Muscle Dysmorphia Symptom Questionnaire (Table 2). Among the most frequent enjoyable activities relinquished by subjects with muscle dysmorphia were social gatherings with friends, family, and significant others. One subject missed his high school reunion for fear that people would mock his “smallness.”

Co-Occurring Psychiatric Disorders

On the SCID-P, the men with muscle dysmorphia reported strikingly higher rates of current or past major mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders than the normal comparison group. Specifically, 14 (58%) of the men with muscle dysmorphia reported a lifetime history of major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder versus six (20%) of the normal comparison men (p=0.005, Fisher’s exact test). Seven (29%) of the muscle dysmorphic men versus one (3%) of the comparison men reported a lifetime history of a DSM-IV axis I anxiety disorder (p=0.02, Fisher’s exact test), and seven (29%) of the muscle dysmorphic men versus none of the comparison men reported a history of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge-eating disorder (p=0.002, Fisher’s exact test). No consistent sequence was found between the onset of muscle dysmorphia and the onset of any of these associated disorders. For example, among the 14 men with muscle dysmorphia who reported major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, the mood disorder began at least 1 year before the muscle dysmorphia in six cases (43%), at least 1 year afterward in six cases (43%), and within the same year in two cases (14%).

Eleven (46%) of the 24 men with muscle dysmorphia but only two (7%) of the normal comparison men reported using steroids—a significant difference (p=0.002, Fisher’s exact test). The mean age at onset of steroid use for all subjects was 20.3 years (SD=2.9, range=15–27). Of the 11 subjects with muscle dysmorphia who reported using steroids, the onset of muscle dysmorphia occurred at least 1 year before the steroid use in eight (73%) of the cases, at least 1 year after using steroids in one (9%) case, and within the same year in two (18%) cases. Although steroid use and withdrawal have been reported to cause mood disorders (15), all of the cases of mood disorders reported by the subjects in this study occurred independently of steroid use.

Sexual Orientation and Behavior

Five (21%) of the men with muscle dysmorphia and five (17%) of the normal comparison men described their sexual orientation as homosexual. These seemingly high rates of homosexual orientation in both groups were contributed almost entirely by men from two gymnasiums serving predominantly gay members. Nine of the 10 subjects recruited from these gymnasiums reported their sexual orientation as homosexual.

The muscle dysmorphia and normal comparison groups exhibited no significant differences on most questions regarding sexual behavior, including age of first sexual intercourse, history of a homosexual experience, and frequency of sexual activity per year. Only the statement “I find myself in awkward sexual situations” elicited a significant difference between groups: 13 (54%) of the subjects with muscle dysmorphia “agreed” or “agreed somewhat” with this statement, versus only four (13%) of the normal comparison subjects (p=0.003, Fisher’s exact test).

Body Image, Exercise, and Eating Behavior

Questions about body image and exercise behavior yielded some of the most dramatic differences between the muscle dysmorphia and normal comparison groups. Specifically, on “I really like my body,” 12 (52%) of 23 muscle dysmorphic subjects versus six (20%) of the normal comparison subjects responded “disagree” or “disagree somewhat” (p=0.008, exact trend test for all four possible responses). Of five options in response to “how dissatisfied are you with the way your body is proportioned?,” 11 (46%) of the subjects with muscle dysmorphia versus three (10%) of the comparison subjects responded “totally” or “mostly” dissatisfied (p<0.001, exact trend test). Similar patterns were observed for the questions “how fat do you feel?” and “how uncomfortable would you be if you could not exercise for a week?” (p<0.001, exact trend test for five options on each scale; data available from Dr. Olivardia). Of course, many of these differences were expected, since they resembled the criteria used to select the subjects with muscle dysmorphia initially. Less expected, however, were the highly significant differences that emerged between the groups on all but one of the subscales of the Eating Disorders Inventory, with subjects with muscle dysmorphia consistently reporting greater pathology. The mean total Eating Disorders Inventory score for the 24 subjects with muscle dysmorphia was 44.3 (SD=26) versus 21.9 (SD=12) for the normal comparison subjects (t=4.2, df=51, p<0.001). These differences remained significant even when the seven (29%) subjects with muscle dysmorphia who reported a current or past history of an eating disorder were excluded from analysis.

Family Environment and Childhood Experiences

Most questions regarding upbringing and family environment, including rates of reported childhood physical and sexual abuse, generated no significant differences between the two groups. However, men with muscle dysmorphia reported less favorable relationships with their mothers than men without muscle dysmorphia (t=2.4, df=52, p=0.02), Seven (29%) subjects with muscle dysmorphia reported that father-mother violence occurred “sometimes” or “often” in their families while they were growing up versus only one (3%) normal comparison subject (p=0.02, Fisher’s exact test). Mother-child violence was reported as occurring “sometimes” or “often” by eight (33%) of the subjects with muscle dysmorphia compared to only one (3%) normal comparison subject (p=0.007, Fisher’s exact test).

Comparison With College Students

Finally, as discussed previously, we compared our two groups of weightlifters with the two groups of college students from our earlier study (3). The weightlifters with muscle dysmorphia closely resembled the college men with eating disorders on lifetime history of mood and anxiety disorders, indices of body dissatisfaction, and Eating Disorders Inventory scores, whereas the normal comparison weightlifters proved strikingly similar to the normal comparison college men on all of these same measures (data available from Dr. Olivardia).

Discussion

This is the first controlled study, to our knowledge, of muscle dysmorphia, a subtype of body dysmorphic disorder in which individuals develop a pathological preoccupation with their muscularity. We found that 24 men with muscle dysmorphia differed strikingly from 30 normal comparison weightlifters on many measures, including body dissatisfaction; eating attitudes; prevalence of anabolic steroid use; and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and eating disorders. Among the men with muscle dysmorphia who reported these co-occurring disorders, the onset of the comorbid disorder sometimes occurred before and sometimes after the onset of muscle dysmorphia itself. Thus, it seems unlikely that one disorder simply caused the other. Instead, a predisposition to both disorders might have arisen from a common underlying environmental or genetic influence. For example, muscle dysmorphia, like other forms of body dysmorphic disorder, may be part of the “obsessive-compulsive spectrum” of disorders (17) or a form of “affective spectrum disorder” (27). If so, it is likely that muscle dysmorphia will respond to treatments already shown to be effective for other disorders in these families, such as cognitive behavior therapy and antidepressant medications.

The phenomenology of muscle dysmorphia appears similar in many ways to the phenomenology of eating disorders. In an a posteriori analysis, we found that the men with muscle dysmorphia closely resembled college men with eating disorders on a wide range of indices, whereas the normal comparison weightlifters closely resembled normal comparison college men without eating disorders. These findings suggest that the earlier term “reverse anorexia nervosa” may be apt: the pursuit of “bigness” shows remarkable parallels to the pursuit of thinness.

Evidence also suggests that, like eating disorders, muscle dysmorphia may be stimulated by sociocultural influences. For example, the ideal male body image, as portrayed by the media, appears to have grown steadily more muscular over the years. Hollywood’s most “masculine” stars of the 1940s and 1950s, such as James Dean, John Wayne, or Jimmy Stewart, did not approach the muscularity of many of today’s action heroes. Similarly, as we have reported elsewhere (28), American action toys, such as GI Joe or the figures from Star Wars, have grown steadily leaner and more muscular from the 1960s to the present. These sociocultural influences were reflected in the comments of several of our subjects with muscle dysmorphia, who reported that they aspired to look like leading current weightlifters and muscular actors.

By contrast, our findings do not support a prominent contribution of family and childhood experiences to the etiology of muscle dysmorphia. On measures of family background, childhood physical and sexual abuse, and current sexuality, few differences emerged between the subjects with muscle dysmorphia and the normal comparison weightlifters. On the other hand, we cannot exclude the possibility that important familial or childhood experiences may contribute to muscle dysmorphia but were not assessed systematically in the present study.

Several methodological aspects of our study should be considered. First, it might be argued that some of the findings for the men with muscle dysmorphia are tautological. For example, since the men with muscle dysmorphia were selected specifically because they were dissatisfied with their bodies, it is hardly surprising that they scored higher than the normal comparison weightlifters on measures of body dissatisfaction. However, many of the other findings in the group with muscle dysmorphia, such as their higher lifetime prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders, use of steroids and other drugs, and higher scores on many Eating Disorders Inventory subscales, cannot be explained as tautological—which suggests that muscle dysmorphia is indeed a valid diagnostic entity, although it is probably only part of a larger spectrum of disorders, as previously discussed.

Second, it might be speculated that weightlifters as a whole represent an atypical group of men, perhaps with a high ambient level of psychopathology, and that muscle dysmorphia simply represents a common cluster of symptoms associated with dedicated weightlifting. Our findings, however, do not support this speculation: of the 39 men who responded to the normal comparison advertisement, only one endorsed all three of our muscle dysmorphia questions on telephone screening, and only eight others endorsed any of the three questions. Although these eight individuals may have exhibited a possible forme fruste of muscle dysmorphia, the remaining 30 men proved closely comparable to a group of unselected normal college men on a wide range of measures of psychopathology. Admittedly, even the normal comparison weightlifters spent a mean of 41 minutes per day thinking about wanting to get bigger (Table 2), and we did not assess this item in the normal comparison college students. On the whole, however, our observations argue that although muscle dysmorphia is associated with substantial psychopathology, weightlifting per se is not.

One possible limitation of our study is selection bias. Since muscle dysmorphia is characterized by shame and embarrassment about body appearance, the most likely direction of bias might be that many individuals with this disorder saw our advertisements but felt too embarrassed to come forward for the study and reveal their problems to an interviewer. Indeed, among the individuals who did participate, several commented that they had hesitated to enroll for fear that we might consider them “too small” or because they were embarrassed to disclose the severity of their preoccupation. For these reasons, we suspect that muscle dysmorphia may be associated with greater morbidity than was suggested by the results of the present investigation.

The investigation also may be affected by information bias, in that subjects may have withheld sensitive information, such as a history of sexual abuse or abuse of anabolic steroids. For example, one subject denied anabolic steroid abuse, but his fat-free mass index measured over 27—a figure virtually unattainable without drugs (20). Finally, the sample investigated in the study was relatively small. Larger groups of men with the symptoms of muscle dysmorphia might reveal further features of the syndrome not found in the present study.

In conclusion, our results suggest that muscle dysmorphia is a valid diagnostic entity and is associated with striking and stereotypical features. By comparison, normal weightlifters without muscle dysmorphia appear similar to normal college students. Thus, our findings suggest that most weightlifters do not exhibit elevated levels of psychopathology, whereas the subgroup with muscle dysmorphia exhibits prominent impairment. Given the severity of this impairment, it would seem important to characterize further the epidemiology of this often-secret syndrome and to investigate potential treatments for it.

|

|

Received Dec. 22, 1998; revision received Nov. 29, 1999; accepted Jan. 18, 2000. From the Biological Psychiatry Laboratory, McLean Hospital; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston; the Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts; and the Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Olivardia, Biological Psychiatry Laboratory, McLean Hospital, 15 Mill St., Belmont, MA 02478; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Garner DM, Garfinkel PE: Sociocultural factors in the development of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 1980; 10:647–656Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, Schwartz DM, Thompson MG: Cultural expectations of thinness in women. Psychol Rep 1980; 47:483–491Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Olivardia R, Pope HG Jr, Mangweth B, Hudson JI: Eating disorders in college men. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1279–1285Google Scholar

4. Mangweth B, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Olivardia R, Kinzl J, Biebl W: Eating disorders in Austrian men: an intracultural and cross-cultural comparison study. Psychother Psychosom 1997; 66:214–221Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mintz LB, Betz NE: Sex differences in the nature, realism, and correlates of body image. Sex Roles 1986; 15:185–195Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Drewnowski A, Yee DK: Men and body image: are males satisfied with their body weight? Psychosom Med 1987; 49:626–634Google Scholar

7. Silberstein LR, Mishkind ME, Striegel-Moore RH, Timko C, Rodin J: Men and their bodies: a comparison of homosexual and heterosexual men. Psychosom Med 1989; 51:337–346Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Fallon AE, Rozin P: Sex differences in perceptions of desirable body shape. J Abnorm Psychol 1985; 94:102–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Dwyer JT, Feldman JJ, Seltzer CC, Mayer J: Body image in adolescents: attitudes toward weight and perception of appearance. Am J Clin Nutr 1969; 20:1045–1056Google Scholar

10. Tucker LA: Relationship between perceived somatotype and body cathexis of college males. Psychol Rep 1982; 50:983–989Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Pasman L, Thompson JK: Body image and eating disturbance in obligatory runners, obligatory weightlifters, and sedentary individuals. Int J Eat Disord 1989; 7:759–769Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J: Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord 1983; 2:15–34Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Blouin AG, Goldfield GS: Body image and steroid use in male bodybuilders. Int J Eat Disord 1995; 18:159–165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Pope HG Jr, Katz DL, Hudson JI: Anorexia nervosa and “reverse anorexia” among 108 male bodybuilders. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:406–409Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Pope HG Jr, Katz DL: Psychiatric and medical effects of anabolic-androgenic steroid use: a controlled study of 160 athletes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:375–382Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Phillips KA, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI: Body dysmorphic disorder:30 cases of imagined ugliness. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:302–308Google Scholar

17. Phillips KA, McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Pope HG Jr: Body dysmorphic disorder: an obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder, a form of affective spectrum disorder, or both? J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56(suppl 4):41–51Google Scholar

18. Pope HG Jr, Gruber AJ, Choi P, Olivardia R, Phillips KA: “Muscle dysmorphia”: an underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder? Psychosomatics 1997; 38:548–557Google Scholar

19. Jackson AS, Pollock ML: Generalized equations for predicting body density of man. Br J Nutr 1978; 40:497–504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kouri EM, Pope HG Jr, Katz DL, Oliva P: Fat-free mass index in users and nonusers of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clin J Sport Med 1995; 5:223–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

22. Phillips KA, Atala KD, Pope HG: Diagnostic instruments for body dysmorphic disorder, in 1995 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1995, p 157Google Scholar

23. Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, Aronowitz BR, DeCaria C, Goodman WK: A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:17–22Medline, Google Scholar

24. Johnson C, Love S: Diagnostic Survey for Eating Disorder—Revised. Tulsa, Okla, Laureate Psychiatric Clinic and Hospital, 1984Google Scholar

25. Finkelhor D: Sexually Victimized Children. New York, Free Press, 1979Google Scholar

26. SAS/STAT Software: Changes and Enhancements Through Release 6.12. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1997Google Scholar

27. Hudson JI, Pope HG Jr: Affective spectrum disorder: does antidepressant response identify a family of disorders with a common pathophysiology? Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:552–564Google Scholar

28. Pope HG Jr, Olivardia R, Gruber A, Borowiecki J. Evolving ideals of male body image as seen through action toys. Int J Eat Disord 1999; 26:65–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar