Study of Stalkers

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This clinical study was devised to elucidate the behaviors, motivations, and psychopathology of stalkers. METHOD: It concerned 145 stalkers referred to a forensic psychiatry center for treatment. RESULTS: Most of the stalkers were men (79%, N=114), and many were unemployed (39%, N=56); 52% (N=75) had never had an intimate relationship. Victims included ex-partners (30%, N=44), professional (23%, N=34) or work (11%, N=16) contacts, and strangers (14%, N=20). Five types of stalkers were recognized: rejected, intimacy seeking, incompetent, resentful, and predatory. Delusional disorders were common (30%, N=43), particularly among intimacy-seeking stalkers, although those with personality disorders predominated among rejected stalkers. The duration of stalking was from 4 weeks to 20 years (mean=12 months), longer for rejected and intimacy-seeking stalkers. Sixty-three percent of the stalkers (N=84) made threats, and 36% (N=52) were assaultive. Threats and property damage were more frequent with resentful stalkers, but rejected and predatory stalkers committed more assaults. Committing assault was also predicted by previous convictions, substance-related disorders, and previous threats. CONCLUSIONS: Stalkers have a range of motivations, from reasserting power over a partner who rejected them to the quest for a loving relationship. Most stalkers are lonely and socially incompetent, but all have the capacity to frighten and distress their victims. Bringing stalking to an end requires a mixture of appropriate legal sanctions and therapeutic interventions.

Stalking refers to a constellation of behaviors involving repeated and persistent attempts to impose on another person unwanted communication and/or contact. Communication can be by means of telephone calls, letters, e-mail, and graffiti, with contact by means of approaching the victim and following and maintaining surveillance. Associated behaviors include ordering goods on the victim’s behalf and initiating spurious legal actions. Threats, property damage, and assault may accompany stalking. Community surveys suggest that 1% to 2% of women report having been subjected to stalking in the previous year, with a lifetime risk of 2% for men and 8% for women (1–3).

“Stalking” is new terminology, but persistent pursuit and intrusion by discarded partners and by would-be lovers with disorders have long been discussed in fictional accounts, such as Louisa May Alcott’s aptly titled A Long Fatal Love Chase(4), in reported legal cases such as the 1840 prosecution of Richard Dunn (5), in nineteenth century psychiatric literature in relation to erotomania (6–8), and more recently in the domestic violence literature (9). The media first used “stalking” to describe intrusions on celebrities by fans with mental disorders, but it was later generalized to cover a range of recurrent harassment behaviors, particularly in domestic disputes. In 1990, California’s anti-stalking law gave stalking an initial legal definition: “willful, malicious and repeated following and harassing of another person” (10). Finally, stalkers and their victims began to be regarded as constituting groups worthy of study by behavioral scientists (11–13). In less than a decade, stalking has been established as a new category of fear, crime, disordered behavior, and victimization.

Stalking, like any complex form of human behavior, can be the product of a number of different states of mind. Stalking, which is obviously hurtful, is part of a spectrum of activities that merge into normal behaviors, often around such aspirations as initiating or reestablishing a relationship. To further complicate definitional issues, central to the construction of stalking—both as a concept and as an offense—are the victim’s perceptions of being harassed and rendered fearful. Thus, it is not just the intentions and behavior of the perpetrator that create a stalking event but how the actions are experienced and articulated by the victim. These complexities have made problematic the generation of a useful classification.

Meloy and Gothard (11) proposed “obsessional follower” as a clinical corollary of “stalker,” perhaps appealing to the Latin derivation from obsessor, one who abides or haunts (14), although “obsessive pursuer” might have been preferable. Zona and colleagues (15), on the basis of 74 cases, suggested that stalkers fell into three distinct groups: erotomanic, love obsessional, and simple obsessional. Harmon et al. (16) developed a classification system using two axes: one, defining the nature of the attachment as either affectionate/amorous or persecutory/angry; the other, defining the previous relationship. A number of other typologies have been proposed, including a simple dichotomy between psychotic and nonpsychotic stalkers (17) and those of de Becker (cited in reference 18), who devised four categories: attachment seeking, identity seeking, rejection based, and delusionally based.

A classification of stalkers should provide a guide to the course and duration of harassment, the risks of escalation to assaultive behaviors, and, above all, the most effective strategies for ending the stalking.

This article provides a description of a group of individuals who persistently stalked others and who were assessed and, in some cases, treated at a specialized forensic clinic.

METHOD

Case materials were gathered between 1993 and 1997 from referrals to two of the authors (M.P. and P.E.M.) at a forensic psychiatric clinic with a known interest in both the victims and perpetrators of stalking. The clinic had received extensive and sympathetic coverage in national and local media, which contributed to high rates of referral. Referrals came from throughout the state of Victoria (population 4.7 million) from courts, community correction services, police, and medical practitioners and, in three cases, following self-referral.

Stalking was defined as repeated (at least 10 times) and persistent (lasting for at least 4 weeks) unwelcome attempts to approach or communicate with the victim. The behavior was considered unwelcome on the basis of the feelings of the victim, not the claims of the perpetrator. Some who were referred after a court conviction for stalking did not meet these criteria and were not included in this series.

Communications were subdivided into those employing telephone calls, mail and facsimile, e-mail, and other, which included graffiti and notes attached to property. Contact was separated into following and maintaining surveillance or approaching the victim. The associated behaviors were divided into either giving, or ordering on the victim’s behalf, unsolicited goods or initiating spurious legal actions. The associated violence was grouped under threats, property damage, and actual assault—both physical and sexual.

The psychiatric classification is by DSM-IV criteria. One nosological difficulty is raised by those who do not believe that their love is reciprocated but are totally preoccupied and insist, with delusional intensity, on both the legitimacy and the eventual success of their quest (19). This group cannot be encompassed by existing DSM-IV criteria for delusional disorder of the erotomanic type, which favor exclusive emphasis on the delusional conviction of being loved, advanced by de Cl象mbault (20), rather than following the far longer tradition of regarding erotomania as the morbid exaggeration of love in all its aspects (6, 8, 19, 21). In this article, subjects with these morbid infatuations are analyzed both separately and combined with those with erotomania, who are absolutely convinced that their love is returned.

Discrete variables were analyzed by means of chi-square analysis. To best predict the variables associated with patterns of harassment and violence, log-linear modeling was used (22). This method is equivalent to using analysis of variance when both dependent and independent variables are categorical. Within this model, both the individual effects of each independent variable (i.e., marginal effects) and the potential confounding between independent variables in the analysis (i.e., partial effects) were considered. Post hoc analyses of significant main effects were assessed using log-linear parameters. This method of analysis allows for a decomposition of significant main effects when an independent variable consists of two or more categories. The effects of individual categories are expressed as z scores. Continuous variables were compared among groups by using analysis of variance, with post hoc analyses of group main effects conducted using Tukey’s honest significant difference. The significance level was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

Our criteria for stalking were met by 145 stalkers, of whom 115 (79%) were male. Ages ranged from 15 to 75 years, with a median of 38 years. Over half of the stalkers (N=75) had never had a long-term relationship; another 41 (30%) were currently separated or divorced. Unemployed stalkers (39%, N=56) made up a substantial proportion of the group, although the majority (56%, N=82) were employed; six (8%) of these occupied professional and senior management positions, six were students, and one (1%) described herself as a housewife. (Data on employment status were not available for eight subjects.)

Duration and Nature of Stalking Behaviors

The duration of stalking varied from 4 weeks to 20 years (median=12 months). The most common method of communicating was by telephone (78%, N=113), often involving multiple calls, the highest being more than 200 in 24 hours. Some stalkers revealed a detailed knowledge of the victim’s movements, tracking them by phone to work, to friends’ homes, and to cafes and bars. Letters were sent by 94 (65%), varying from the occasional note to a daily deluge. Eight notes were attached to the victim’s property, six messages were scrawled on walls, and two were cut into the paint of the victim’s car. Two flooded the object of their attention with e-mail messages.

The stalkers maintained contact by repeated approaches in public situations (86%, N=124) and through surveillance and persistent following (73%, N=106). Surveillance equipment, such as cameras and audio transmitters, was resorted to by four stalkers, three employed detective agencies, and three persuaded acquaintances to aid in their pursuit. One stalker obtained a license to operate as a private investigator, and another hired a helicopter to maintain surveillance.

Although some stalkers favored one particular form of harassment, only three confined themselves to a single approach. In 92 cases, between three and five methods were employed, and 16 of the stalkers used seven different forms of harassment.

Associated Behaviors

Unsolicited gifts were sent by 69 stalkers (48%), including flowers, chocolates, self-help books, and pictures of the stalker, but more grotesque offerings included mutilated photographs of the victim and a dead cat. Goods and services were ordered on the victim’s behalf—the most common being pizza, often delivered in the early hours of the morning—including ambulances, magazine subscriptions, and airplane tickets. Spurious legal actions were initiated by 12 stalkers, which included litigation aimed at forcing contact, as well as accusations of stalking and harassment intended to preempt the victim’s pursuit of legitimate legal redress.

Threats and Violence

Threats were made to the victim by 84 (58%) of the stalkers and to third parties by 56 (39%). Thirty-six (25%) threatened only the victim, eight (6%) only third parties, and 48 (33%) both. Property was damaged by 58 (40%), the most common target being the victim’s car. Fifty-two (36%) attacked the victim, and nine (6%) assaulted third parties. These attacks were intended to frighten and physically injure someone in 38 instances but in 14 were primarily sexual assaults. The physical injuries were largely confined to bruises and abrasions, but one victim sustained a fractured jaw and one received stab wounds. The sexual attacks involved six indecent assaults and eight attempted or accomplished rapes.

Relationship to Victim

The stalkers were ex-partners in 44 (30%) of the instances; 34 (23%) had had a professional relationship with the victim, most often a medical practitioner. Initial contact had been through work-related interaction with fellow employees or customers in 16 cases (11%). Casual acquaintances made up 28 (19%) of the victims, with 20 (14%) having no previous contact with the victim. There were three stalkers of celebrities. Twelve women stalked women, and nine men stalked men.

Psychiatric Status

Sixty-two stalkers had an axis I diagnosis. Forty-three had delusional disorders, 20 of which were of the erotomanic type; five morbid jealousy; three persecutory and 15 morbid infatuations categorized as unspecified. Fourteen had schizophrenia, five of whom had erotomanic delusions; two had bipolar disorder; two, major depression; and one, anxiety disorder. The primary diagnosis was personality disorder in 74 men, with the majority falling into cluster B. Comorbid substance-related disorders were noted in 36 (25%) of the stalkers. There were 59 stalkers with psychosis (delusional disorders, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder).

Criminal Histories

Fifty-seven (39%) of the individuals had previous criminal convictions; 41 (28%) were for interpersonal violence and 10 (7%) were for sexual offenses. One had a previous stalking conviction.

Motivation and Context

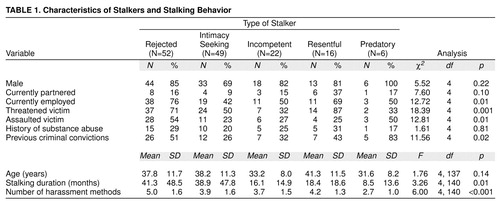

On the basis of context and motivation, five groups were constructed: rejected, intimacy seeking, incompetent, resentful, and predatory (Table 1).

Stalking was the response of 52 subjects to the rejection of a relationship, most frequently involving an ex-partner (N=41) but also occurring with estrangement from the mother (N=2), a broken friendship (N=6), and disrupted work relationships (N=3). Rejected stalkers often acknowledged a complex mixture of desire for both reconciliation and revenge. A sense of loss could be combined with frustration, anger, jealousy, vindictiveness, and sadness in ever-changing proportions. The majority of the rejected stalkers had personality disorders, although nine had delusional disorders, five involving morbid jealousy.

Forty-nine stalkers were seeking intimacy with the object of their unwanted attention, whom they identified as their true love. Twenty-seven had erotomanic delusions and believed that their love was reciprocated; 20 of these had delusional disorder of the erotomanic type, five had schizophrenia, and two had mania. The remaining 22 intimacy-seeking stalkers were made up of those we termed to have “morbid infatuations” (15), together with those with personality disorder (7) who persisted in their pursuit without absolute certainty of eventual success. The central purpose of the intimacy-seeking stalkers was to establish a relationship, but several were prey to jealousy, and a number became enraged at their would-be partner’s indifference to their approaches.

The 22 we classified as incompetent stalkers acknowledged that the object of their attention did not reciprocate their affection, but they nevertheless hoped that their behavior would lead to intimacy. This group included intellectually limited and socially incompetent individuals whose knowledge of courting rituals was rudimentary, together with men with a sense of entitlement to a partner but no capacity, or willingness, to start by establishing some lesser form of social interaction. The incompetent stalkers had often previously stalked others. They regarded their victims as attractive potential partners, but, unlike those seeking intimacy, they did not endow them with unique qualities, were attracted but not infatuated, and made no claims that their feelings were reciprocated.

The 16 we termed resentful stalkers stalked to frighten and distress the victim. Eight pursued a vendetta against a specific victim, but the remainder had a general sense of grievance and chose victims at random. Such a stalker persistently pursued a young woman because she appeared, when glimpsed in the street, to be attractive, wealthy, and happy when the stalker had just experienced a humiliating professional rejection. Another man stalked a medical practitioner who he believed had failed to diagnose his wife’s cervical cancer.

The six predatory stalkers were preparing a sexual attack. These men took pleasure in the sense of power produced by stalking, and there were elements of getting to know their victim and rehearsing, in fantasy, their intended attack. Such stalking could be prolonged before they either attacked or were apprehended. One predatory stalker sought help after reaching the point of equipping an isolated house, acquiring ether and ropes, and being poised to abduct the victim. Predatory stalkers predominantly had paraphilias and were more likely than all other diagnostic groups to have previous convictions for sexual offenses (χ2=57.00, df=4, p<0.001).

Predictors of Type and Duration of Stalking

The number of harassment methods used varied according to the proposed clinical typology (F=5.99, df=4, 140, p<0.001); rejected stalkers had the widest range of behaviors in comparison with all other groups with the exception of resentful stalkers (Table 1). Diagnosis was also associated with the number of harassment behaviors (F=3.04, df=4, 140, p<0.02), with those with personality disorder using the most stalking methods.

Log-linear modeling was used to predict whether typology and diagnosis were associated with particular types of harassment. Both diagnosis (χ2=12.61, df=4, p<0.01) and typology (χ2=15.57, df=4, p<0.01) were independently associated with calling by telephone, although neither variable remained significant when confounding between the factors was considered. Predatory stalkers were the least likely group to telephone (z=–2.87, p<0.01), in contrast with rejected stalkers, who most frequently used this method of harassment (z=2.93, p<0.001). Letter writing was also predicted by both the diagnosis of delusional disorder (χ2=11.14, df=4, p<0.02) and typology (χ2=9.40, df=4, p<0.05), with intimacy-seeking stalkers predominating, although neither group’s results remained significant when confounding between the variables was considered in the partial analysis. Following and maintaining surveillance were associated with diagnosis (χ2=12.16, df=4, p<0.01, partial effect); stalkers with personality disorder were twice as likely as other groups to follow their victims (z=3.30, p<0.001). Unwanted approaches and sending unsolicited materials were not significantly associated with either typology or diagnosis. When the results were analyzed with either morbid infatuation excluded or included in delusional disorder, no differences emerged.

Stalking duration was related to clinical typology (F=3.26, df=4, 140, p<0.01). Post hoc analyses demonstrated a nonsignificant tendency for rejected stalkers and intimacy-seeking stalkers to be the most persistent (Table 1). Duration was unrelated to diagnostic group or gender.

Association With Threats and Violence

Less than half (48%, N=40) of those who threatened their victims proceeded to assault them, but the 77% (N=40) who assaulted had previously threatened their victims (χ2=11.14, df=1, p<0.001). Log-linear modeling was used to predict the relationship between threats and violence and the independent measures of typology, diagnosis, history of substance abuse, and previous criminal convictions. Threats to the victim were predicted independently by previous convictions (χ2=7.89, df=1, p<0.01), substance abuse (χ2=3.90, df=1, p<0.05), and typology (χ2=9.40, df=4, p<0.05); resentful and rejected stalkers were more likely to threaten their victims. When confounding between variables was considered in the partial analyses, however, only previous convictions remained significant (χ2=5.62, df=1, p<0.02), thus accounting for most of the explained variance with threats. Property damage was predicted independently by both substance abuse (χ2=7.52, df=1, p<0.005) and previous convictions (χ2=4.70, df=1, p<0.03), although only substance abuse remained significant when all variables where considered (χ2=5.65, df=1, p<0.02). Assault was predicted by previous convictions (χ2=15.61, df=1, p<0.001) and substance abuse (χ2=5.04, df=1, p<0.03), and there was a nonsignificant trend for typology (χ2=8.40, df=4, p<0.07). Only previous convictions remained significant, however, when all variables were considered (χ2=10.44, df=1, p<0.001).

Specific diagnoses were not associated with threats or violence, but nonpsychotic stalkers were more likely to commit assaults (43%, N=37) than were psychotic stalkers (25%, N=15) (χ2=4.42, df=1, p<0.05), although they were equally likely to threaten their victims.

Response to Management Strategies

A full analysis of treatment response is ongoing, but certain patterns are discernible. Intimacy-seeking stalkers require assertive psychiatric management, particularly because they are largely impervious to judicial sanctions, often regarding court appearances—even imprisonment—as the price of true love. In contrast, many rejected stalkers can be persuaded to desist by fines or potential incarceration, although usually not those embroiled in child custody disputes or those who are morbidly jealous. Incompetent stalkers abandon the pursuit of their current victims with relative ease, but the challenge is to prevent them from choosing others. Resentful stalkers, who usually evince considerable self-righteousness, are difficult to engage in treatment, and legal sanctions tend to inflame rather than inhibit their sense of grievance and the associated stalking. Predatory stalkers, because of the nature of their planned offense, are primarily a criminal justice problem, but there is a role for psychiatrists in the treatment of their paraphilias. With our self-referred potential predator, therapy has to date prevented him from committing a sexual offense and prevented a return to stalking.

Those with major mental disorders require treatment, but given that delusional disorders predominate in this population, this is no easy matter and requires considerable psychotherapeutic skill in addition to pharmacotherapy and more general support. Those with personality disorders are a disparate group, but most can benefit from a combination of support, social skills training, and psychotherapy.

DISCUSSION

This study was clinically based, with a study group skewed to the severe end of the spectrum of harassment and more likely to contain those with obvious mental disorders. It is probable that in the State of Victoria, several thousand women and men were victims of stalking during the study period, but only 284 stalkers were convicted (23), and only 145 are included in this report.

Stalkers come predominantly from the lonely, isolated, and disadvantaged of our society but can include individuals from the whole social spectrum. Similarly, victims are not selected exclusively from the famous but can be almost anyone. One is most likely to be stalked by an ex-partner, but also at particular risk are those such as psychiatrists, whose profession brings them into contact with isolated and disordered individuals, in whom sympathy and attention are easily reconstructed as romantic interest.

Stalkers were grouped into rejected, intimacy-seeking, incompetent, resentful, and predatory types. These are not entirely mutually exclusive groupings, and the placement of an individual is a matter of judgment. This typology of stalkers overlaps with several proposed previously (15, 16, 18). The incompetent group is, however, unique, and although it could arguably be incorporated into the intimacy-seeking group, differences in the imagined relationship to the victim, the pattern of stalking, and the response to treatment justify its separation. Intimacy-seeking stalkers form a spectrum, from those with erotomania to those with morbid infatuations to rigid, obsessive individuals whose attraction to the victim has produced persistent pursuit. There are different management imperatives in intimacy-seeking stalkers, from the grossly deluded to fixated individuals, but, interestingly, the problems they share of being isolated, lonely, socially inept, and filled with an inflated sense of entitlement present the greatest therapeutic challenge. Rejected stalkers comprise the largest group, formed predominantly, but not exclusively, of ex-partners; they overlap with the “simple obsessional” grouping of Zona et al. (15) but exclude those whom we have placed in a separate group called resentful stalkers. The predatory stalkers form a small group within this series but are important to recognize given their potential for sexual violence. With sexual offenders, some elements of stalking are relatively common, but the usefulness of treating such individuals as stalkers remains to be investigated. This typology, when combined with diagnosis, provides a basis for management decisions and, in combination with criminal convictions and substance abuse, predicts the likely nature and duration of stalking and the risk of assault. This typology, however, remains a tentative proposal because it is only with the experience of larger and less selective populations that a reliable classification with robust predictive value can be established.

Diagnostically, stalkers often fit within the spectrum of those with paranoid disorders. Intimacy-seeking stalkers include those who have erotomanic delusions, both secondary to preexisting psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and as part of a delusional disorder. True delusional disorders, which are common in intimacy-seeking stalkers, merge imperceptibly into the overvalued ideas and fanatical obsessiveness of those with personality disorder, with the boundaries often uncertain and changing. With rejected stalkers, there is a spectrum in which the tenacious clinging to a relationship in inadequate individuals merges into the assertive entitlement of the narcissistic and the persistent jealousy of the paranoid. Resentful stalkers present, in contrast, an almost pure culture of persecution, with paranoid personalities, delusional disorders of the paranoid type, and paranoid schizophrenia.

Stalkers are, as has been previously noted, atypical as offenders (11, 15, 24); offenders tend to be younger and more often substance abusers with histories of conduct disorder in childhood and criminal offenses in adulthood. Compared with the state’s public mental health patients, stalkers are more than twice as likely to have a previous conviction for violence and also more likely to have comorbid substance abuse disorder (25% versus 15%) (25). Stalkers’ profiles are intermediate to those of offenders and of mental health patients, as to some extent are their behaviors and psychopathology.

Effective strategies for ending stalking involve an appropriate combination of legal sanctions and therapy. The majority of rejected stalkers will desist under the threat of prosecution, but their continued abstinence is assisted by an appropriately supportive and directive therapeutic relationship, which will usually be with a mental health professional but can be with a parole officer. Intimacy-seeking stalkers always require psychiatric intervention, although compliance may require a court order or—in extreme cases—incarceration. Predatory stalkers are primarily a criminal justice problem, although management of their paraphilic disorder may be relevant to reducing recidivism. The incompetent stalker requires augmented interpersonal sensitivity and communication skills, which are easier to prescribe than produce. In our experience, resentful stalkers are the most difficult to engage, although time attenuates their bitterness and drive for revenge.

Stalkers who are strangers and overtly mentally ill produce the most fear in victims, but those who assault are most likely to be rejected ex-partners. Histories of previous offenses, comorbid substance abuse, and the issuing of threats all predict assault. Predatory stalkers are a special case, and here there is a troubling lack of warning of danger because they are the least intrusive stalkers, often only glimpsed by their victims, who may report fear but are not certain they are being followed. Resentful stalkers are threatening and prone to damaging their victim’s property, but, interestingly, they rarely proceed to overt assault. The overall risk presented by intimacy-seeking stalkers is low, but, in our experience, those with erotomania and morbid infatuations can, on occasion, be responsible for extreme violence (19).

Studies of stalking are in their infancy, with only the beginnings of answers to who stalks, why they stalk, and, most important, how to stop them. Stalkers inflict considerable damage on their victims, whether or not they resort to actual assault (26). A small proportion of stalkers are the predatory stalkers of so many dramatic presentations, but many are lonely, distressed people whose behavior wreaks havoc in their own lives as well as those of their victims. Therapy can usually help stalkers and often is the most effective way of lifting the burden from their victims.

Received May 26, 1998; revision received Nov. 23, 1998; accepted Jan. 4, 1999. From the Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health, Melbourne; the Department of Psychological Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Melbourne. Address reprint requests to Dr. Mullen, Forensic Health Administration Bldg., Mont Park Hospital, Waiora Rd., Macleod 3085, Australia; [email protected] (e-mail) Supported by a postgraduate award from the Australian government to Ms. Purcell.

|

1. Domestic Violence and Stalking: The Second Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, July 1997Google Scholar

2. Australian Bureau of Statistics: Women’s Safety. Canberra, Australia, Government Printer, 1996Google Scholar

3. Tjaden P, Thoennes N: Stalking in America: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey: Research in Brief. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 1998Google Scholar

4. Alcott LM: A Long Fatal Love Chase (1866). New York, Random House, 1995Google Scholar

5. English Law Reports: Regina vs Dunn, Queen’s Bench, Case 599, 1840, pp 939–949Google Scholar

6. Esquirol JED: Mental Maladies: A Treatise on Insanity. Translated by de Saussure R. New York, Hafner Press, 1965Google Scholar

7. Kraepelin E: Manic-Depressive Insanity and Paranoia. Translated by Barclay RM, edited by Robertson GM. Edinburgh, E & S Livingstone, 1921Google Scholar

8. Krafft-Ebing R: Text Book of Insanity. Translated by Chaddock CG. Philadelphia, FA Davis, 1904Google Scholar

9. Jason LA, Reichler A, Easton J, Neal A, Wilson M: Female harassment after ending a relationship: a preliminary study. Alternative Lifestyles 1984; 6:259–269Crossref, Google Scholar

10. California Penal Code 646.9 (West, 1990; suppl, 1994)Google Scholar

11. Meloy JR, Gothard S: Demographic and clinical comparison of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:258–263Link, Google Scholar

12. Pathç, Mullen PE: The impact of stalkers on their victims. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:12–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Meloy JR: The psychology of stalking, in The Psychology of Stalking. Edited by Meloy JR. San Diego, Academic Press, 1998, pp 2–21Google Scholar

14. Lewis CT, Short C: A Latin Dictionary. London, Oxford University Press, 1879Google Scholar

15. Zona MA, Sharma KK, Lane J: A comparative study of erotomanic and obsessional subjects in a forensic sample. J Forensic Sci 1993; 38:894–903Medline, Google Scholar

16. Harmon RB, Rosner R, Owens H: Obsessional harassment and erotomania in a criminal court population. J Forensic Sci 1995; 40:188–196Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kienlen KK, Birmingham DL, Solberg KB, Oregan JT, Meloy JR: A comparative study of psychotic and nonpsychotic stalking. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1997; 25:317–334Medline, Google Scholar

18. Orion D: I Know You Really Love Me: A Psychiatrist’s Journal of Erotomania, Stalking and Obsessive Love. New York, Macmillan, 1997Google Scholar

19. Mullen PE, Pathç: The pathological extensions of love. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:614–623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. de Cl象mbault CG: Les psychoses passionelles, in Oeuvres Psychiatriques. Paris, Presses Universitaires, 1942, pp 315–322Google Scholar

21. Kretschmer E: Der Sensitive Beziehungswahn (The sensitive delusions of reference) (1918), in Themes and Variations in European Psychiatry. Edited by Hirsch SR, Shepherd M. Bristol, UK, Wright, 1974, pp 152–195Google Scholar

22. Dixon WJ (ed): BMDP Statistical Software Manual, 1990 ed, vols 1 and 2. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1990Google Scholar

23. Criminal Justice Statistics and Research Unit: Stalking Statistics, Changes in 1996/97: Stats Flash Number 29. Victoria, Australia Department of Justice, 1998Google Scholar

24. Schwartz-Watts D, Morgan DW, Barnes CJ: Stalkers: the South Carolina experience. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1997; 25:541–545Medline, Google Scholar

25. Wallace C, Mullen PE, Burgess P, Palmer S, Ruschena R, Browne C: Serious criminal offending and mental disorder: a case linkage study. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172:477–484Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hall DM: The victims of stalking, in The Psychology of Stalking. Edited by Meloy JR. San Diego, Academic Press, 1998, pp 115–136Google Scholar